J. Edgar Hoover: Bureaucracy, Autocrats, and Xi Parallels

ALSO: McCarthyism vs. Hooverism, MLK, stamping out communism with boredom, and an FBI informant scoping out Chairman Mao

J. Edgar Hoover — what does his life story illustrate about the nature of bureaucracy? What themes do McCarthyism and almost the entire history of the Cold War illustrate about contemporary US-China relations? And why does Hoover, in the way he ran the FBI, remind me of Xi?

To discuss, we have Yale’s Beverly Gage, who recently wrote — and I do not use this term lightly — a magisterial new biography of J. Edgar Hoover.

Childhood Trauma and Early Xi Analogues

Jordan Schneider: Who is J. Edgar Hoover, and why is he interesting?

Beverly Gage: John Edgar Hoover was one of the most important political figures in the twentieth century of the US. He was most notably head of the FBI — and he was head of the FBI for forty-eight years.

So he has this amazing career that spanned the 1920s through the 1970s. He became FBI director in 1924 under Calvin Coolidge, and died in the same job in 1972 under Richard Nixon. And the story of the FBI is basically the story of his life.

Jordan Schneider: For some of our international readership who haven’t necessarily had that much FBI in their lives: he was instrumental in McCarthyism; he played an instrumental role in America’s response to the Cold War, particularly on the home front; he had a lot to do with the FBI’s messy involvement in the American civil rights movement. And he is also a lens to look at the professionalization and upgrading of American national security and state capacity more generally — turning something considered unimportant enough that they gave a guy in his twenties responsibility over it, into the world’s largest and most-important investigative criminal agency on the planet in world history.

So seeing those threads — as well as what it means to basically govern as (can we say) an autocrat in a democratic system over decades — was such an interesting and unique lens into thinking about American history.

So let’s jump back to his youth — which was horrific. Let’s do a little childhood trauma tour. Why was life so rough for Hoover as a youth?

Beverly Gage: Well, he was a child of Washington, DC — so a lot of this book is about Washington as a city with its own particular culture and politics.

He was born there in 1895, and the way that he often described his childhood was as this idyllic time, a time of innocence, a time when everything was very clear and people were very moral and upstanding — often the ways that people describe their childhoods in retrospect.

But as I began to do some research on his family, I found a whole series of pretty deep traumas that he hadn’t talked about. I don’t know if that was a deliberate covering-up per se; Hoover was certainly not above that. But that, I concluded, must have shaped him as a child.

Before Hoover was born, one of his grandfathers committed suicide in a pretty dramatic way in the Anacostia River: he basically tied himself to a stake and drowned there, in the midst of a major financial crisis. His suicide made headlines across the city during his own childhood.

His aunt (his mother’s brother’s wife) was murdered in a murder-suicide — that, again, made headlines across the city.

And then probably the most immediate piece — and one that I was able to explore a little bit but that the sources are pretty thin on — was his own father’s mental illness and depression. And ultimately, his father basically died of depression when Hoover was a young man.

Jordan Schneider: So the Xi parallels are strained but interesting to contemplate: Xi grew up in the Cultural Revolution and had his whole universe of family trauma.

But, like Hoover, Xi came out on the other side of that being really one who bought into the system and the order and structure that, in Xi’s case the Party, and in Hoover’s case American bureaucracy could give to help them make sense of their lives and meaning.

Beverly Gage: Hoover was very ambitious as a young man, and he seems to have responded to a lot of these circumstances coming from a struggling middle-class family. His father had a government job, but not a great one. And so Hoover went through the public school system. He then stayed in Washington, went to George Washington University at night while he worked by day in the Library of Congress.

But throughout all of it, you can see a really intensive energy, a real ambition — he was valedictorian and head of the debate team — and he took a lot of that energy and skill and applied it to the art of bureaucracy. And he had this incredibly swift rise through the Justice Department.

Jordan Schneider: Before we get to that job — Hoover threw himself into the Library of Congress cataloging various books and whatnot in the new Dewey Decimal System (which was the coolest thing in information technology in the early twentieth century).

You have this great line: when he was applying to get a permanent position in the Justice Department after World War I, his recommendation letters said that “he works hard and industriously, putting a lot of overtime work, and is really diligent.” But no one says he’s brilliant — rather, it was this deep drive and psychological need to put all these things in boxes that ended up really enabling him to distinguish himself from his peers.

Beverly Gage: He was always drawn, even as a young man, to institutions that had a couple of things going for them:

They tended to be pretty hierarchical — the cadet core of his high school, his fraternity (in some sense).

They were homosocial — so he really liked men’s organizations.

Now, that wasn’t so unusual in the early twentieth century, but he was in the cadet corps and the fraternity and the Masonic order and all of these other institutions where men gathered together to the exclusion of women.

And then he really liked rules and systems.

So that was key at the Library of Congress where he really learned to order information with this relatively new information technology. And then he carries a lot of that ethos of wanting very clear rules and hierarchies into what he does at the Bureau.

The Federal Government, 100 Years Ago

Jordan Schneider: I want to paint a portrait of what the federal government could and couldn’t do in the first half of the twentieth century. Folks were shocked at how limited it was.

Could you give us a bit of a portrait of capacities that we in 2023 may have expected bureaucrats in Washington to be able to do but which were, frankly, impossible (given the funding systems, quality of people in these organizations at the time)?

Beverly Gage: So Washington was a backwater, it was a second-rate city — and that was partly because the federal government didn’t have the capacity that we think of it having today.

The federal government was very involved in a few things. One was the post office, which was probably the place that most Americans encountered the federal government in the most serious way. Of course, you’ve got a small army which is active around the world and on the North American continent in various ways. And you have a scattershot series of other duties and abilities at the federal level — but it’s really a grab bag. There’s very little of the social welfare apparatus that we think of today.

And in Hoover’s case, there’s very little of either the law enforcement or intelligence apparatus. I mean, there basically is no federal intelligence system prior to World War I.

And so Hoover is just there on the ground floor as the security state is being invented, as the intelligence system is being invented, and really as federal power is going to explode over the course of the twentieth century. And that was some of the happenstance of his life: one of these contingent moments is that he happened to be born and then to graduate into a world where all of this is being reinvented — and he’s part of that invention process.

Jordan Schneider: So, World War I passes, and all of a sudden America decides it needs to spy on citizens. How does that happen, and what role does Hoover play in it?

Beverly Gage: Hoover happened to graduate from law school in the spring of 1917, just as the United States is entering World War I.

Hoover doesn’t go into the military. Instead, he goes straight into the Justice Department, which has this explosion of new things that it needs to do during the war. It is supposed to be enforcing a whole set of draconian new speech laws that have been created to prevent people from criticizing the war or advocating revolution or labor resistance or draft dodging.

Hoover’s first duty in the Justice Department is with German internment — which is something that we tend to forget about, but there were several thousand German citizens who were interned in various ways during the First World War.

So that was his big experiment as he entered during the war: German internment and registration. He turned out to be so good at it that, when the war came to an end, and the Justice Department was thinking about what its peacetime apparatus is going to look like, and they decide to create a new little division called the Radical Division — which is supposed to be its first peacetime effort at conducting surveillance of political radicals in the United States, mainly anarchists and communists and black activists — and they put Hoover in charge of this, at the age of twenty-four.

So he’s rising fast already, and he’s shaping all of these ideas about communism, anticommunism — the Bolshevik Revolution has just happened, and Hoover is there on the ground floor as the new American communist parties come into being.

Jordan Schneider: Interesting echoes from the Cold War — xenophobic sentiment throughout American history. When World War II started, you had no more playing of Wagner and Beethoven; people stopped eating sauerkraut and hamburgers; and this goes all the way to mob violence — which is difficult to comprehend: I mean, when you think of violence in America in that era, you think more of race riots. But the idea that that could be directed at Germans in the context of World War I was very striking to me.

We’re going to do your other book in two minutes — what was so scary for the American establishment about all these labor-activist groups that Hoover was supposed to keep tabs on?

Beverly Gage: It can be hard for us to imagine today because we know how the story plays out — but in 1917, 1918, 1919, there are lots of people in the United States who are really worried about a left-wing revolution, something like the Bolshevik Revolution that had just happened in Russia. And of course, you’re seeing revolutionary ideas and movements sweep across Europe during and after the war.

And there’s lots of labor unrest in the United States. There are a series of really dramatic terrorist bombings aimed at government officials and major capitalists. And there is a profusion of new radical groups coming into being, too.

So, all of that combined produces what I think we have to understand as overblown but also genuine concern that the United States was going to erupt in some big wave of social violence, and, potentially, attempts to overthrow the government. And Hoover comes in at the age of twenty-four as one of the officials in charge of stopping that.

Jordan Schneider: I mean, if you thought that balloons are scary, just imagine bombs going off once a month across the entire US.

So labor in particular — how can we see the origins of COINTELPRO in what the Justice Department ended up doing to try to undermine these groups?

Beverly Gage: The first place that Hoover really made a dramatic impact on the American political scene was as head of the Radical Division at the age of twenty-four, when the Attorney General — a guy named A. Mitchell Palmer — turns to Hoover to help organize a series of deportation raids that are going to be aimed at first anarchists and then communists.

And the federal government basically goes in, raids people who are having political meetings, and arrests them all. The first round of raids, which is aimed at anarchists, is wildly popular and successful. And Hoover, very dramatically, gets an old warship that they nickname “the Soviet Ark” — and they take these 200-some anarchists and say, “We’re sending them back where they belong: Bolshevik Russia.” And they load them all on this ship — and this includes some famous people like Emma Goldman, who was the most famous anarchist in the United States, if not the world, at the time — and they are, in fact, permanently deported.

In January 1920, there’s a second round of raids aimed at the Communist parties, and these become much more controversial. They’re larger scale, which produces a big civil-liberties backlash.

And so if we look back on the Palmer Raids — what does Hoover learn from that episode?

You could see his anticommunist ideas in very rapid formation. He writes some of the first briefs on communism and the Communist Party ever produced in the federal government.

You see him encountering criticisms — and organizations like the ACLU, which is just getting started, are going to be big critics and people that he has to contend with throughout his lifetime.

And then the third thing that I think he really concludes from all of that: the problem with the Palmer Raids wasn’t that they were wrong or that they violated civil liberties. It was that it was done too publicly, that everyone could see what was going on. And you had all these pictures of federal agents banging people over the head and such — so that from now on, it would have to be done much more quietly. This surveillance would come in-house. And that is really his philosophy for a lot of the time that he’s director of the FBI.

An Autocrat in a Democracy

Jordan Schneider: So coming to his lifetime focus on communism — I guess it hits a lot of psychological, neuralgic points, as well as being a real career accelerant for him. If you’re in charge of the Radical Division, of course you want all of America freaking out about radicals, particularly the scary foreign ones.

Can you disentangle the psychological as well as bureaucratic factors that ended up leading him to focus on communism for almost fifty years?

Beverly Gage: Well, they are very hard to disentangle. One of the things that’s great about Hoover as a biographical subject — and then also one of the things that’s challenging — is that he himself was not terribly reflective about where he ended and the Bureau began, or where his ideas ended and the rest of the country began. He always would have seen a deep fusion between what he felt was right and what served him and what served the Bureau, the country, and the cause of anticommunism — for Hoover, these were all identical.

And I think what’s really interesting about him as an anticommunist — and as someone who formed that outlook in this early period when revolution and violence and those kinds of conflicts are so central to these questions — is that he doesn’t come to see communism as just a national-security question. He goes on to deal with Soviet espionage, the Cold War, infiltration of the government — but throughout his life, he really sees this as a grand, existential struggle that is cultural and social, as well as political and security-oriented, and that has to do with race and religion. And he targets a lot of people who are progressives or liberals as being dupes of the communists. He just sorts his world into good guys and bad guys — that’s pretty consistent for most of his career.

Jordan Schneider: I think we start to see some more Xi echoes here — particularly with the idea that there is no such thing as reasonable dissent: anyone who is disagreeing with me is fundamentally being subversive and is an enemy of the Party or the Bureau or the American way of life, as the case may be.

Beverly Gage: Over the course of his career, Hoover would often make gestures toward the need to respect dissent, toward democracy as being really essential to the American way of life, toward the need for constitutional limits and constraints on the FBI. And in fact, a lot of people applauded and supported him — strangely enough, from our perspective — as a civil libertarian within the government, or someone who could have been a lot worse.

And yet temperamentally, and in many ways politically and ideologically, he was almost totally intolerant of dissent: that was within the Bureau itself as he built it; that was any criticism of him or the Bureau that occurred in the press, in the public at large — he would immediately retaliate. And he was always entirely convinced of his own righteousness — the righteousness of his vision of the world, the righteousness of the cause that he was serving. And he really did understand people who couldn’t get on board as enemies and subversives.

And of course, he had an apparatus — the FBI. He had pretty strong control over and was there to enforce his vision of what America should be like and how Americans ought to think and act.

Jordan Schneider: I want to stay on the “thinking democracy is worthwhile” theme for a little bit.

I’ve been reading up on George Kennan recently, and it’s been striking to me both how Kennan in particular just thought democracy was annoying and deeply unhelpful to furthering state interests. And Hoover sometimes said things that seemed like he believed it was possible for the state to go overboard. But the answer that he always seemed to keep coming to was, “Give me and the national-security state more power, and we’ll take care of this. Citizens, do not be alarmed. Just let us do our thing, and all your problems will be solved.” Any pushback from the people was always a negative.

Reflections on that dynamic? Or just more generally in the twentieth-century milieu, how many people actually thought democracy was a true asset (not something we have to put on and over to a side when competing in World War I, World War II, and then in the Cold War)?

Beverly Gage: One of the things that interested me in writing about Hoover was actually to turn our lens away from the way that we often narrate the twentieth century in American politics — elections, political, parties, candidates, presidents, legislation — and to really look at the part of the state where most governance happens and where, in fact, democratic accountability was not very strong or powerful for a lot of the twentieth century. And so Hoover is interesting in his own right. He’s interesting as a representative of the security state and, more broadly, the administrative state — which goes through such a dramatic expansion in the twentieth century.

And then you have the question of how he took these tools of power and what he did with them. To me, the really interesting political puzzle of Hoover is that I think he was a real believer in professionalism, in expertise, in “leaving it to the professionals,” in science, in federal power — all of these ideas that we tend to describe as being essential to progressives in building the mid-century liberal state.

And yet at the same time, he was this deep ideological conservative on race, communism, religion, law and order. And he put those two pieces together to build this conservative bastion within the liberal state.

It’s an interesting tension. I think it was less unusual during his lifetime than it is now, when that combination of things is almost impossible to imagine.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stick with the culture question. What was the vision of the system and the people that inhabited the system he was trying to create? And how did he realize that vision through hiring and organizational practices over the years?

Beverly Gage: When he became director in 1924 — he was just twenty-nine years old — he was brought in as a reformer. And his main charges were:

To get the FBI out of the objectionable political surveillance practices and civil-liberties violations that it had been engaged in. (Now, of course, he had been deeply involved in that work — but he was young, he was fresh, he was making new promises.)

And then the other was to clean up its corruption and patronage problems. And he spent most of his first decade as director really just focused on perfecting the bureaucracy.

His first initiative was to revamp who an agent was. He wanted only college-educated men. He wanted lawyers and accountants. He wanted to hire people who were a lot like him — which meant they probably went to George Washington University or joined his fraternity or some similar fraternity. They were white men of a certain age with a certain outlook on the world that were basically extensions of Hoover.

And then he spent a lot of time making things like new rules and new manuals and hiring standards and putting in place a lot of the things that we still have as the FBI’s expert practices right now. This is when Hoover took over counting crime statistics — so when you hear the FBI’s crime statistics today, that comes from early Hoover. He established the FBI lab. He established its training facilities for police — et cetera.

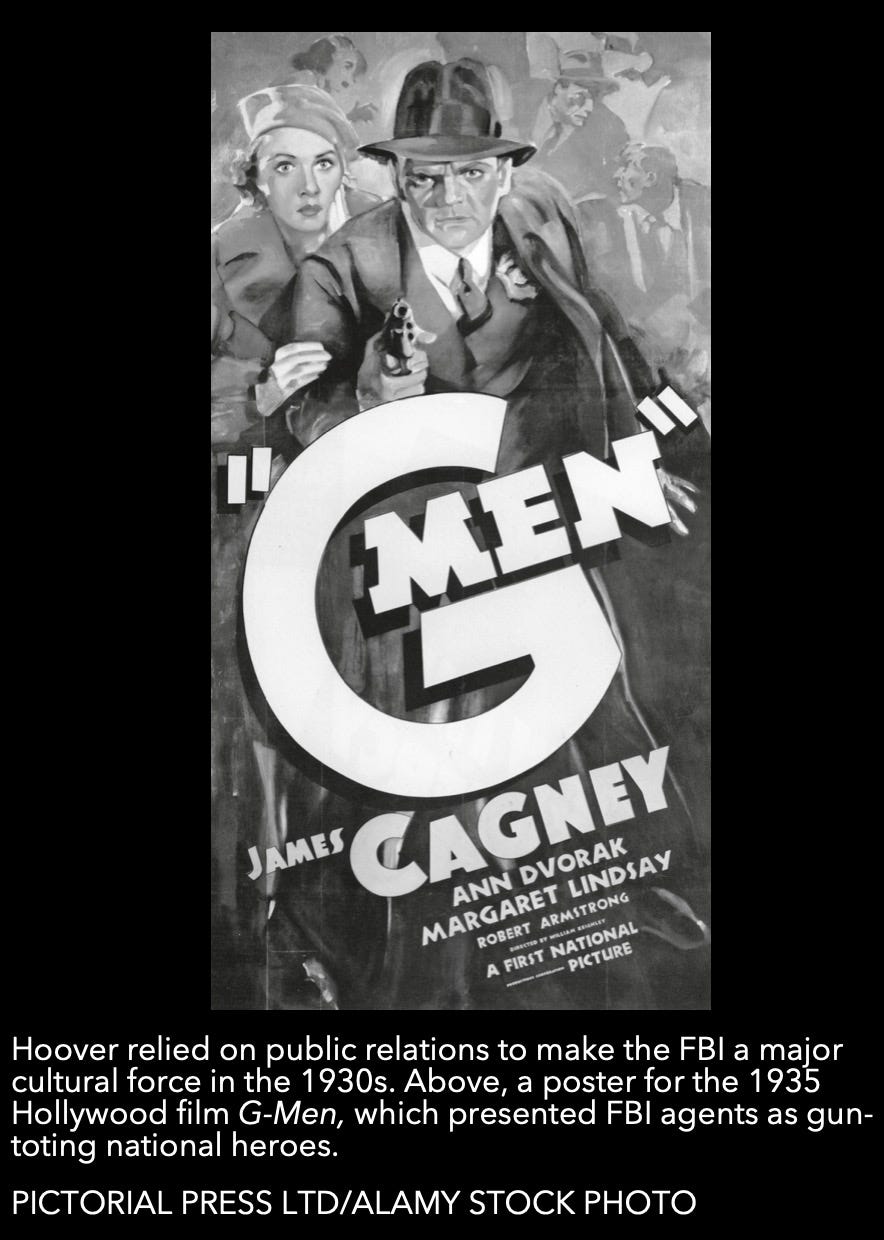

All of these were in the vision of making the FBI this elite, highly professionalized, very conservative corps of white men who would go on to be known as “G-Men,” or government men, when they became more famous in the mid-1930s.

Jordan Schneider: I think it’s an interesting point you make — you have a few pages where you describe what police work before the FBI: it was corrupt, it was violent, there were forced confessions, and for a lot of street-level crime, it was really an extension of the criminal universe.

So the idea that he wants to professionalize and raise the status of fighting crime makes a ton of sense. When it leads to you only hiring white frat brothers who played sports and who have a certain jawline and their lips aren’t too big and stuff — I mean, you really end up getting this very narrow vision of what civil servant you wanted. And it’s funny in the subsequent decades where he’s like, “Oh man, all of my people are fighting World War II. I guess I got to bring in a handful of blacks.” And then you tell a story where someone got fired because he had a girl over for a night — and this was around 1965, and this guy sues Hoover: “What planet are you on? This is the 1960s. I can’t believe I’m losing my job over this.”

But that vision of order and functioning that he takes from his pre–World War I years and pastes onto the next fifty years of running this organization was a really interesting thread that you pulled out.

Beverly Gage: FBI employment really was a totalizing experience. You got moved around a lot, somewhat randomly. Hoover had very high expectations for the overtime that you were going to put in. He had high expectations for how you were going to go to church, and where you were going to go to church, and who you were going to date, and what your family life was going to be like.

And maybe most importantly, he made a very big point over the course of his whole career of keeping his agents out of the civil service so that he himself had almost total control over their hiring and firing and selection. If they had been in the civil service, he would have had a pool of candidates who would not all have been these nice, white frat boys that he wanted — but because he kept them out of the civil service, he was able to create this institution with an incredibly powerful internal culture.

And there’s a reason that if you say, “FBI agent,” most Americans today still picture something very particular: they picture a tall white guy in a suit. And that was Hoover’s product.

Jordan Schneider: CCP parallels — I don’t know if they abound, but it’s almost like a Leninist corps, maybe, of the change that Hoover wanted to see in America.

So, speaking of the person on top: the leadership style was also really interesting to watch — how Hoover was able to really turn this into his domain.

Beverly Gage: He was, and he did it amazingly over this vast period of time when you would think there’d be some turnover in an appointed position like this. But he served under eight different presidents — four of whom were Democrats, four of whom were Republicans — and he managed to achieve bureaucratic autonomy within the government such that he had his fiefdom that very few other people could influence, or even penetrate.

Now, he definitely understood himself to be a servant of the Attorney General to some degree, but certainly of the president. And so he was not someone who refused to follow the political priorities of those above him — though at strategic moments, he did often resist, or people learned not to ask him to do things they thought he wasn’t going to do. But within the state itself, he just had, by any measure, a really extraordinary amount of autonomy and control over what started out as a few hundred agents — but by the time he hit, his late career was many, many thousands.

Jordan Schneider: I’ll stop with the Xi stuff for a second and bring in a better parallel — which is Robert Moses. He also grew up in this progressive era, and was this young, hotshot reformer — and then ends up becoming an unelected power center for decades.

What interesting dynamics did you see between him and Hoover? Did they ever meet each other? They must have, right?

Beverly Gage: They might have. I never found that moment — but Hoover spent a lot of time in New York and was involved in lots of the institutions, the press associations and clubs, and he used to hang out at the Waldorf all the time. So surely they came across each other, though they weren’t especially close.

One of the things that Hoover and Moses shared was a generational story, that they both were unique to their moment — in the sense that they came along, they were ambitious, young bureaucrats who gained their skills in the 1910s and 1920s, just before the moment that government power and ambition was going to explode. And it meant that they were then in the right place at the right time to be part of that expansion.

That accident of timing meant that there weren’t a lot of controls at that point. When Hoover becomes head of the Bureau in 1924 at the age of twenty-nine, no one foresees that you’re going to have this colossus who’s going to be the center of federal law enforcement and domestic intelligence. It’s just this little group of investigators that do stuff for the Justice Department.

And so I think the same thing is true of Moses when he comes into those positions: there’s not a lot of sense of how much power is actually concentrated in those positions, and there aren’t a lot of mechanisms of accountability. Those are going to come later for both of them toward the end of their careers — and then really after their deaths, when everyone reckons with what they’ve built.

Jordan Schneider: Another interesting parallel between them is, man, these guys know how to play the game.

Hays Code, Venona, and McCarthyism vs. Hooverism

So we’re into World War II, and Hoover helps Harry Hopkins spy on his wife — that must just be the tip of the iceberg of Hoover knowing how to work the angles and keep his masters happy.

Beverly Gage: I think the popular image of Hoover is that he both got and then maintained his power by strong-arming everyone. He has the secret files, he’s intimidating people — and he certainly did plenty of that, particularly later on when he really was in this incredibly powerful position — but one of the things that I tried to do in the book was to look at all the other sources and techniques of power that he was able to deploy.

On the one hand, he had these very consistent ideas, say, about communism or about law and order that he maintains for his whole career. On the other hand, he is incredibly flexible in responding to crisis, in responding to the needs and priorities of powerful men above him and in doing favors for them.

One of the reasons that he stays in power for so long is not just that presidents were afraid of him — and there’s some truth to that, albeit I think it’s somewhat exaggerated — but because he was so useful to them. And you see that beginning to really develop in the Roosevelt years.

Same thing with Congress: he’s really good at developing his relations with Congress. He’s good at developing his relations with the press, with his own popular constituency. He’s got this vast array of tools that he works with to build a base for himself.

Jordan Schneider: So a few angles of that which were fascinating: all these ex-agents end up being congressional staffers, and then he gives them little tidbits to make their bosses look smart so that the next time appropriations comes around, he gets the plus-ups he wants.

But the really interesting thing, and one of the most striking things of this book, is his public-opinion ratings for decades and decades were eighty- or ninety-percent approval. Can you talk a little bit about the public-outreach efforts and image-shaping of both Hoover and the FBI more generally that allowed that gave him this “immortality” — this armor of being more popular than the more powerful people ostensibly above him in the Washington power rankings?

Beverly Gage: In a lot of ways, I think the most surprising part of the book was not my deep dives into the secret FBI archives but was this very public fact: although we think of Hoover as one of the great villains of the twentieth century, for most of his career he was incredibly popular. He had high approval ratings, especially in the 1940s and 1950s. He lasts through Democratic and Republican administrations. He has widespread support in Congress — and there are a number of reasons for this, but one of them is that he turns out to be incredibly skilled at public relations.

And in fact, he devotes a whole part of the FBI to public-relations outreach on a wide array of sorts. Some of it is just articles in the press and managing the press. Some of it is outreach to Hollywood — which, to his everlasting benefit, decides in the 1930s under the film codes that they are only going to make crime movies if the cops win. That makes Hoover’s G-Men these great heroic figures — and that code lasts for most of his time there. So he benefits from that.

Jordan Schneider: Are there pre-Code movies about corrupt cops?

Beverly Gage: There are: starting in the 1920s when “talkies” came in, a lot of those early films were pretty dark, dystopian crime movies — extremely violent, romanticized criminals, a lot of drugs, sex, drinking, and all of these things that Hollywood decided in the 1930s they were going to ban from films.

And so that’s why we get the two twin beds, the married couples who don’t even sleep in the same place — not because that’s not how people really behaved; it’s just what the codes dictated. And the same thing held true for the police always getting their man.

Jordan Schneider: The original Scarface is the one that first comes to mind.

We’re going to do more China parallels: just being able to dominate the information space and control how people think of you — and Hoover has such a powerful lever over these folks because he can get them blacklisted and ruin their careers. So of course no one in Hollywood is going to want to cross Hoover. And it takes until the late 1960s and 1970s for that armor to start to get chipped away by cultural trends and skepticism in government — which is much broader than anything that Hoover really had power over.

I do think Robert Moses had a bit of a revisionist-history push over the past few years, particularly as it’s been more and more difficult to build anything in America and as you’re seeing high-speed rail not happen and the Second Avenue subway costs $50 billion or whatever it is.

I wonder to what extent you think that, in a world of heightened US-China relations and Cold War 2.0, the next Hoover biography may take a slightly more sympathetic view to the consensus you presented in your book.

Beverly Gage: It’s been interesting to see the reaction. So I think my book is a fair account of Hoover — and actually is probably more generous toward him in lots of ways than most other biographies have been. But it is not especially sympathetic, and I am certainly not suggesting that J. Edgar Hoover is the model of the future.

But, I would say a couple of things have been interesting along these lines. One has been the very recent partisan shift on whether or not people like the FBI: the Republicans right now are the ones investigating the FBI, hostile to the FBI; Republicans are much more critical of the FBI in public-opinion polls — and that’s an almost total reversal from the moment of Hoover’s death, in which the politics looked very different.

The one place that I would say I have seen some interest in thinking about Hoover as a model is precisely in the amount of autonomy that he was able to have — which did allow him to resist untoward requests, sometimes from presidents and from others. It certainly made him unfireable. James Comey was fireable in a way that J. Edgar Hoover was not. And I think there was a way in which Hoover’s interest in the FBI as an institution and the concentration of power he had insulated it from politics that he wanted to insulate it from.

And then he was also pretty good at negotiating when the FBI is being drawn into highly politicized investigations: the Kennedy assassination, a variety of other big, high-profile, highly controversial, highly political investigations — there are lots of things to criticize about what he did there, but he did have ways of managing the political volatility of those moments in a way that I think, maybe, recent FBI directors might have some admiration for, because it’s actually a hard thing to do.

McCarthyism: A Deep Dive

Jordan Schneider: One thing that really struck me was that, particularly in the 1940s and 1950s, he wasn’t seeing ghosts. There were lots of spies everywhere, and the appeal of the Soviet idea in the late 1930s through the 1950s was something that actually created a lot of problems for the US government trying to keep hold of state secrets.

I think that is something that just wasn’t out from the archives until relatively recently, and I think you make a pretty compelling case in the book that, in fact, he held on to this a little too long — and especially when he takes this fear of communism and puts it on Martin Luther King, Jr. and the civil rights movement more generally; that was really unfair and ended up leading to some of the darkest chapters in modern American history. But that also seems like an interesting piece of revision — just how worried America should have been about communism and communist subversion in his early years.

Beverly Gage: One of the reasons that I wanted to write a new Hoover biography was that most of the early biographies had come out in the late 1980s and early 1990s — and they’re good books for the most part, but they didn’t get to take advantage of the post–Cold War moment and all of the revelations that have come out about Soviet espionage, about the nature of the Communist Party in the United States.

So I thought it was going to be really interesting — and it was — to try to reinterpret Hoover through the lens of what we now know. And there are a number of records of secret operations that have come out that have shown actually, yes, there was quite a lot going on in the United States — that a lot of the people who were these high-profile, controversial figures, the FBI had pretty good reason to think that they were, in fact, guilty (figures like Julius Rosenberg and others).

And then there were some really interesting cases where, particularly through the Venona project — this secret Cold War decryption project in which they had actual Soviet intelligence cables and were able to decrypt them in pretty limited ways, but in significant ways — the FBI actually found a whole bunch of people who were clearly involved in espionage, but who they then couldn’t prosecute because they wanted to hold on to a secret. They wanted to keep the Venona project going; they didn’t want to let everyone know what they knew. And so on the one hand, you get these prosecutions — but on the other hand, there are actually a bunch of people who they were pretty sure about but who they just let go off into the world.

And I think the question, then, is if we accept that x number of people were in fact involved in Soviet espionage, what’s the relationship between that and this vast cultural, political phenomenon known as the Red Scare? And that’s a really interesting set of questions.

Jordan Schneider: This is another contemporary theme: yes, it’s real — but how many lives are you going to ruin in the process? And how bad are type I versus type II errors?

Why don’t you talk a little bit about Hooverism versus McCarthyism, and the tensions between how both of those people tried to address this in the early 1950s.

Beverly Gage: I argue in the book that, although we tend to think of Joe McCarthy as the ultimate anticommunist figure (we talk about McCarthyism), Hoover is ultimately the more important figure.

McCarthy came on the national scene in a big way in 1950. By 1954, he is being censured by the Senate and essentially forced out of American political life, and he dies of alcoholism in 1957. So he’s big and showy — but he’s not there for very long, and he doesn’t do a lot of lasting institution building.

Hoover, on the other hand, is there doing anticommunist work for decades, even before McCarthy, and especially in the 1940s. And his approach is really to use the bureaucracy of the FBI and all of the relationships that he’s built to solidify this anticommunist machine. It’s not only the FBI itself — which has these big surveillance and infiltration operations aimed at a huge range of people inside the Communist Party and out. He’s also working with congressional committees; he has a whole secret program to keep governors and school educators and state and local officials informed with FBI information; he has a massive press initiative and press network which is willing to publish what he wants about this; he’s publishing his own books; he’s making speeches.

Hoover is really institutionalizing all of this in ways that are going to last. So, McCarthy is run out of American politics and then dies. And Hoover is just there saying the same thing with this much more powerful apparatus.

Jordan Schneider: I love this little note you had: once the Army–McCarthy hearings roll up — “Have you no sense of decency, sir?” — the AP US History version of that is, “Okay, that’s when McCarthyism peaked.” But no — the next month, Hoover gets all these extra powers by Congress to allow the FBI to get more active in rooting out Communist sympathies, basically with the rationale being, “Yeah, Communism is still scary, but we’re just going to have Hoover do it because he’s a safer pair of hands.”

And then that leads to thousands of primary school teachers losing their jobs, because apparently you can’t have a second grader have communism whispered to their ear, because that’ll be the downfall of American civilization.

Beverly Gage: Right: we tend to think about Hoover and McCarthy as being more or less interchangeable. But at the time, they were seen as these radically different kinds of figures.

And in fact, both the Truman administration and then especially the Eisenhower administration — they championed Hoover, they got behind him, they cheered him on and gave him lots of new power and presented him as the responsible, state-based, rule-bound alternative to Joe McCarthy, who was the liar and the demagogue.

Now, of course, we know the ways in which that really wasn’t entirely true of Hoover. But even now, there’s enough truth to it that it makes sense that those folks would have rallied behind Hoover as they were attempting to cast out McCarthy.

Jordan Schneider: So earlier you mentioned this idea that Hoover wrote a book and then he just made the entire world buy it — another little Xi parallel.

Operation Solo: How the FBI Spied on Chairman Mao

But I do want to get to Operation Solo, which is maybe the wildest story I didn’t know about. Hoover had an informant meet with Mao!

Beverly Gage: Yes, that is an amazing story — and to anyone who likes to nerd out in archives and weird historical documents, I highly recommend the Solo files.

Solo was one of the FBI’s most treasured and most secret operations that began in the late 1950s and lasted through the 1970s. In essence, there were two brothers; they had been in the Communist Party; they had grown a little disaffected from the Communist Party; and in the late 1950s, the FBI persuaded them both to reenter the Party. And then, when the Soviet Union went around searching for international couriers — someone to better build up the relationship between the American Communist Party and the Soviet Union — the FBI managed to maneuver these two informants into getting those jobs.

One brother was the international financial courier of money from the Soviet Union into the US Communist Party. And the files are great: they’re just marking every bill; they’re keeping tabs; they’re not holding the money back — they’re letting millions of dollars pass through from the Soviets, through the FBI, which notes them all and then passes them along to the Communist Party.

And then the other brother, a guy named Morris Childs, was the international representative of the Communist Party. And so he is sent around the world as the emissary of American Communism. He goes to the Soviet Union several times, meets with big dignitaries there. He goes to China — he meets with Mao and meets with other high government officials. He goes to Cuba. He’s just all over the world, meeting all of these folks and then coming back and telling the FBI what he has found.

For people who are interested in that history, I would say one of the most amazing things about those Solo files — and there are hundreds of sections, thousands of pages — is that they would also try to bring back primary material. They would bring back tchotchke, they would bring back programs, minutes of meetings — and so there’s this whole social history archive of global radicalism and communism that’s just sitting there in these FBI files.

But they kept this up through the 1970s — then they were getting pretty old, and when Reagan became president he had a secret medal ceremony for them (because the whole thing was still entirely secret) and lauded them as great Americans who had served the cause.

Jordan Schneider: Wow — and no one’s written a book about it, right?

Beverly Gage: There is a book called Operation Solo, but it was published before all of these files came out — so it was based on interviews with those guys, and it was a journalist who knew them pretty well. So it gives you a broad overview, but there’s lots more in the files now.

Jordan Schneider: The other crazy thing is they were at the Kremlin when JFK was killed, and this must have been the most important thing they’ve done. The data point that they provided was Khrushchev was freaking out, worried that this was going to start World War III — which I think is as good as evidence exists that JFK’s murder wasn’t a Communist plot (though, I mean, who knows? maybe it was two levels deep: they knew he was a spy, and they just wanted to send it this way). But that accident of history is unbelievable.

Beverly Gage: That moment was really amazing.

And then the Solo files actually in some ways first came to light because they were also the ones who — less through their international stuff than through just their involvement in the domestic Communist Party — had told the FBI about a guy named Stanley Levison, who was part of the secret financial apparatus of the Communist Party and then went on to become a very close adviser to Martin Luther King, Jr. And so they are also a through-line from the FBI’s Communist investigations to their concerns about Levison that ultimately became a vehicle for the really terrible things they did to King.

Paid subscribers get advanced access to the second half of our conversation. We discuss:

The ins and outs of COINTELPRO, one of the FBI’s most notorious — and illegal — series of projects;

COINTELPRO’s anticommunist origins, and how a 1956 Khrushchev speech spurred Hoover to action;

The FBI’s dark and bizarre tactics to infiltrate and disrupt “subversive” political organizations;

The early CIA-FBI rivalry;

Why Lyndon B. Johnson as POTUS had special leverage over Hoover — and how Hoover’s operations influenced the 1964 Democratic Convention as well as the civil rights movement;

Gage’s best archival find: the letter that the FBI sent to blackmail Martin Luther King, Jr. — followed by a counterfactual discussion about whether Hoover could have prevent King’s assassination;

“Elder autocratic tendencies” — why men like Hoover and Xi just won’t resign.