Kissinger + Communist Quaaludes, Tang Dynasty Animated

Fentanyl echoes in Kissinger conspiracy theories

This edition of ChinaTalk is brought to you by Matter.

Hey! Do you read?

If so, I have one weird trick to make your life infinitely better. For years, I’ve had a, to be honest, more hate than love relationship with Instapaper and Pocket. I spend hours each day reading articles to get informed and find topics for ChinaTalk shows, but the process of centralizing all that reading was so frustrating with crappy apps that didn’t do what I wanted. So, I just read less, spent more time on twitter, and was dumber for it.

For the past six months, I’ve subbed out these apps for Matter, a modern reader and podcast catcher and have spent at least an hour a day with it ever since. The experience is clean, brings in both articles I find online as well as newsletters from my inbox, and even allows you to listen to articles and highlight podcasts.

If you download Matter, you’ll read more, enjoy yourself while doing it, and just get smarter. How many other apps can actually deliver on that?

To learn more, go to getmatter.com.

Kissinger and the Communist Quaaludes: Why did Lyndon LaRouche think Kissinger was running a Chinese drug ring?

Dylan Levi King reports from the dredges of the twentieth-century conspiracy ecosystem

Did you know that Henry Kissinger was leading a wing of Queen Elizabeth II’s drug trafficking empire? Well, not actually, but this was a real conspiracy theory…

Memories are short: every idea that bubbles up seems like it must be new. We talk today about Chinese fentanyl production poisoning the American heartland, for example, in the context of present-day trade conflicts or ahistorical Opium War revenge fantasies. In many ways, it is only the latest iteration of an idea that has shallow roots.

In the 1950s, Commissioner of Narcotics Harry J. Anslinger — consumed with the threat of communism and committed to expanding the nationwide war on drugs — promoted the idea that Red China was flooding the United States with heroin. Chinese links to heroin seizures around Asia and the United States were found or fabricated — and it wasn’t difficult, since much of the Golden Triangle trade was controlled by Nationalist troops or gangster allies.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the same sort of rumor centered on an illicit drug campaign against American troops in Vietnam, with Red China blamed for getting servicemen hooked on potent heroin for sale at R&R hubs in Thailand and Japan. Again, there was not much evidence for Chinese involvement in the trade, and much more implicating American intelligence agencies and their allies.

While some tried to link China to crack cocaine in the 1980s (Joseph D. Douglass, Jr.’s Red Cocaine: The Drugging of America does this at book length), the more popular iteration of the story dealt with a sedative called methaqualone, marketed for a time as Quaalude, and now sold as Mandrax.

A story in The Washington Post from June of 1982 lays out the facts:

China is said to export legally large quantities of the sedative to free ports in West Germany through normal trade channels under its generic name methaqualone. Brokers in West Germany, in some cases working in collusion with illegal traffickers, ship the drug to Mexico, Colombia and Canada, where it gets diverted into illicit channels and eventually is smuggled into the United States, U.S. officials said.

Although American officials say they have no evidence directly linking China to illegal exports of the much-abused depressant, they blame Peking for failing to adopt commercial safeguards that could keep Quaalude off the illegal market.

The mundane reality — a share of licit production was diverted to the black market after exit from a Chinese port — fed more sensational accounts, which conveniently absolved dealers and consumers in the United States of blame.

Paula Hawkins, Republican senator from Florida and spiritual successor of Anslinger, contributed more than most to selling to the American public the idea that the Chinese were tranquilizing America. This campaign against China was also behind her eventual undoing: when she ran for re-election in 1986, Bob Graham torched Hawkins for claiming in a television advertisement that she had confronted Deng Xiaoping at a Beijing banquet and demanded he stop selling Quaaludes in America. That claim turned out to be false, and contributed to Graham’s landslide victory.

It wasn’t long before Quaaludes disappeared. The DEA won, working with partners in West Germany, Hungary, and China to halt the epidemic before it had the chance to grow worse.

But the story kept going. The Red China drug campaign story, like all conspiracy theories, is open-ended. Whatever truth it contains, more untruths can be stuffed in. It can be used to motivate the fight against communism, distract from CIA planes loaded with Golden Triangle scag, or even bolster drug warrior bonafides in a Florida senate race. It can be expanded even to include Kissinger as the puppetmaster.

That was the theory pushed in a January 1990 issue of Executive Intelligence Review (EIR), a publication founded by Lyndon LaRouche, a renegade right-wing activist, perennial third-party candidate for President, and brilliant conspiracy theorist.

In what is billed as an excerpt from a revised edition of an EIR omnibus called Dope, Inc.: Boston Brahmins and Soviet Commissars (it came out with a different subtitle: The Book That Drove Kissinger and the Anti-Defamation League Crazy), the editors describe Kissinger’s long term role — back to before “Communist Quaaludes” came on the scene — running cover for the sprawling Chinese drug trade:

It was Henry Kissinger who clamped down on any discussion in the West of the Chinese Communists’ role in global drug trafficking. Although it was widely known, and of course admitted, by Beijing’s leaders that the P.R.C. had produced and trafficked dope to American GIs in Vietnam, by the end of the Nixon administration Kissinger had squelched all mention of the P.R.C. as a drug source, in the interests of his new “China card” policy for a Washington-Beijing rapprochement. Kissinger’s effort involved not only protection of the P.R.C. but the subversion of Nixon’s entire 1971 anti-drug crusade.

Key to covering up China’s drug trade was the perpetuation by Kissinger of what EIR calls “the hoax of the Golden Triangle” — the wholesale fabrication of widespread opium production in Southeast Asia to conceal cultivation and processing operations in Yunnan.

Kissinger, according to EIR, sat at the center of a spider web that incorporated Chinese heroin and methaqualone production, illicit logistics operations stretching between East Asia and North America, and global Chinese organized crime networks from Bangkok to Boston.

All of this could be traced back, of course, to LaRouche’s idea that the British Crown was responsible for much of the world’s illicit drug trade, and that Kissinger was one of its agents.

Apart from the historical trivia, there is also a more timely lesson here about the figure of Kissinger in particular, who, given his formal and informal involvement with innumerable political figures and institutions over a career spanning six decades, seems to be the ideal vessel to contain a wide range of theories or fantasies.

That was the purpose Kissinger served for LaRouche, who saw him lurking around every corner. He often was! There was nobody better to slide into the center of the spider web.

长安三万里 China’s Animated Tang Dynasty Blockbuster

The inability to produce animation that rivals South Korea or Japan in global impact is a kind of sore spot for Chinese soft power, particularly as many young Chinese are dedicated anime fans. The most recent Chinese attempt at an animated blockbuster is Chang An 长安三万里, a three-hour, partially fictionalized biography of Li Bai 李白 — one of the greatest Chinese-language poets to ever live. Told through the eyes of Gao Shi 高适, a friend of Li’s and fellow poet, the film covers the rise and fall of the Tang golden age 唐朝 (approximately 650 to 755 AD). The film released in early July and grossed 1.6 billion yuan (US$220 million) in 22 days, becoming the second-highest-grossing domestic animated film in PRC history.

Chang An arrives at an interesting juncture, as Beijing looks to Central Asia for influence and Chinese popular culture revives interest in the country’s medieval prominence through trends like hanfu. Tang-dynasty China, and particularly its capital Chang’an (which is present-day Xi’an 西安, Shaanxi 陕西), was a remarkably cosmopolitan place, as trade and political ties extended across Eurasia via the Silk Road. Interest in the exotic, particularly the cultures of Central and West Asia, was so great that for a time, dressing in kaftan-like styles was extremely popular. Chang’an, then the largest city on earth, was home to diverse peoples and fascinating fusions in artistic styles.

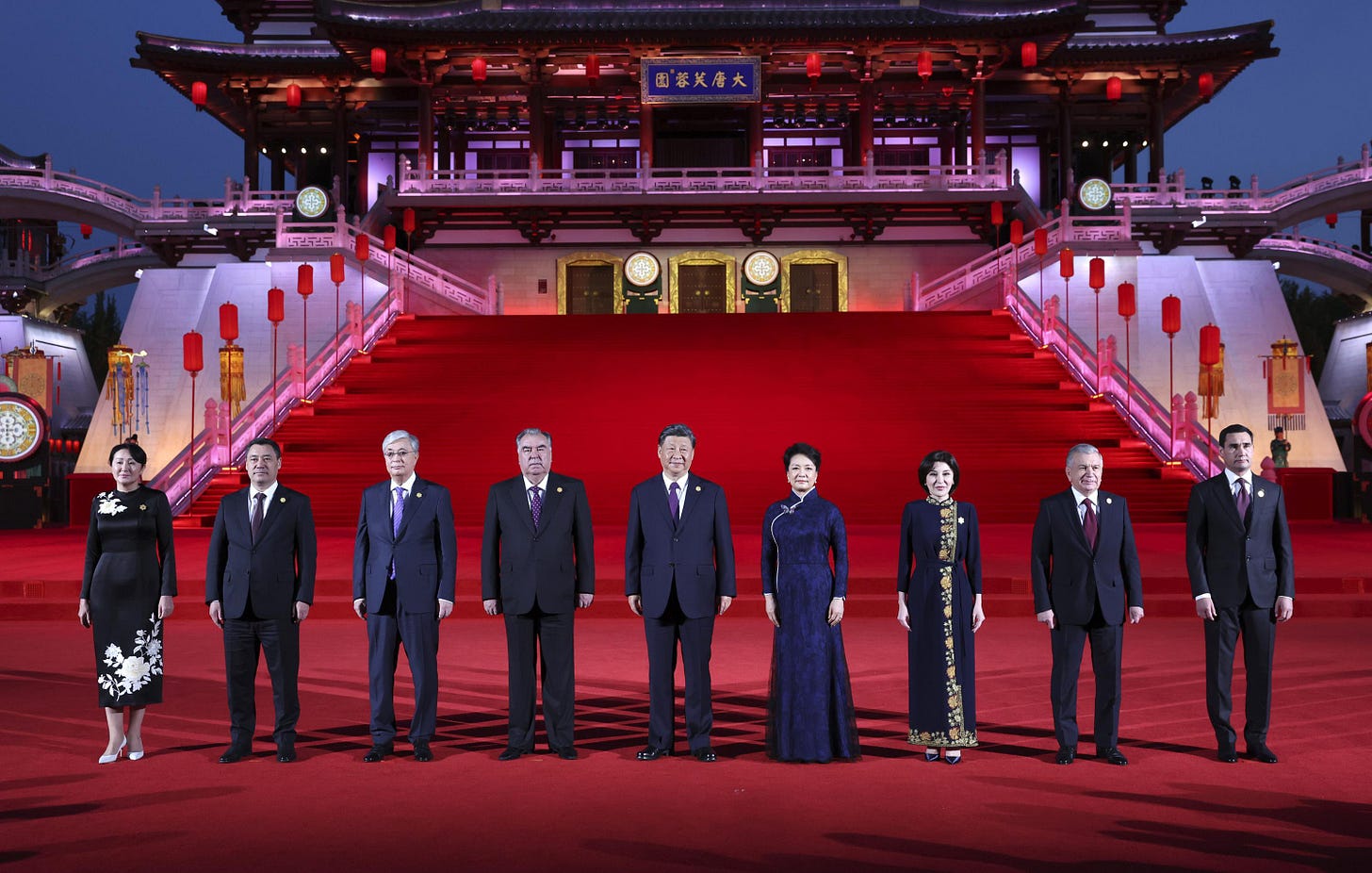

The most overt display of China’s conscious revival of Tang history is probably Xi Jinping’s reception for Central Asian leaders, held in Xi’an in May 2023. The imagery speaks for itself:

Contemporary Chinese popular history holds that the Tang was a time when all nearby nations looked up to China, and Tang generosity is sometimes held up as a model for China’s engagement with the world. Chang A leans into this zeitgeist with rosy, if stereotypical, portrayals of the great ancient capital, replete with belly dancers, elephants, and Li’s poems being sung to “exotic tunes.” In this respect, the film quite powerfully shows ancient Chinese poetry as it is meant to be enjoyed. While most Chinese people (and Chinese-language learners) today study classical poetry exclusively through pen-and-paper, much of the canon was likely originally set to music and sung for enjoyment.

Watching Chang An at a time when the number of foreigners in China has plunged very low is a somewhat disconcerting experience. Certainly, the film is not about geopolitics — it’s arguably more about poetry — but the story implicitly makes Tang diversity and largess seem aspirational. Some part of the Chinese psyche is torn between wanting China to be as open to the world as Chang’an once was, while also insisting on a contemporary national identity that perhaps does not permit such exuberant celebration of the foreign.

The awkward conflict between Tang history and contemporary tensions is most obvious when the film tries to portray the “northern tribes,” some of whom were loyal to the Tang while others frequently assaulted its frontiers. A major plotline concerns Gao Shi’s military career, particularly his leadership of a Tang army tasked with battling the Tibetan Empire. The Tibetans are portrayed as primitive, but also formidable foes. “Northern tribe” characters are treated with various suspicion, but the film also lionizes Geshu Han 哥舒翰, a famous Tang general of Turkic descent, for his loyalty to the Chinese Empire (never mind that in actual history, he defected to the rebel An Lushan 安祿山 after a critical loss). Li Bai himself was probably born in what is now modern Kyrgyzstan; the film does passingly acknowledge his “exotic origins,” but otherwise sidesteps his disputed ethnicity. The Tang’s actual relationships with Central Asian groups are an uncomfortable topic for the filmmakers, who are evidently eager to portray “ethnic unity” à la contemporary PRC propaganda, but must also face historical facts.

The Tang’s peoples lived before race and nationalism became such powerful ideas. The PRC today is a place where Han ethnonationalism rises, while Turkic and Tibetan minority groups face particularly harrowing repression. Telling stories about the Tang reveals some deep longings for a more globally favoured China, but adapting Tang worldviews to today’s PRC is ultimately an ahistorical exercise.