Lessons from the Ultimate China Watcher: László Ladány

“I’m trying to think of who might agree with that sentiment and support a warming of relations. One doesn’t easily come to mind, but I’ll think it through further!”

This article was written by Anthony Edwards, a 2023 graduate of the Hopkins-Nanjing Center. If you like his work here, consider sending him a job offer!

Also, for ChinaTalk fans in the tri-state area, I’m hosting a meetup today at Pier 57 at West 15th Street on the Hudson. I’d love to see you there!

Seventy years ago, the work of one bespectacled Jesuit revolutionized the West’s understanding of China. His level-headed analysis, steeped primarily in Chinese-language sources, helped build the floor that stabilized almost four decades of cooperation between China and the West. His lessons are in desperate need of re-learning.

If we can return to China watching as developed by Fr. László Ladány S.J. (1914-1990), we will see that a passion for Communist Party source material, paired with the belief that this media can reveal meaningful projections of the CCP narrative, will give us the skills we need to rebuild the floor for the US-China relationship. And if we fail to revive the basic principles of Ladány’s China-watching paradigm, this relationship will only continue to crumble.

Ladány’s Roots

When Fr. Ladány arrived in Beijing in 1940, it was not clear that Jesuit work in China was anywhere near its end. Indeed, for centuries Jesuit missionaries persevered in both missionary and scientific work under many emperors across two dynasties. Why should another dynastic change mean anything different for this lasting, albeit occasionally turbulent, mission?

But the twentieth century didn’t just bring another dynastic change — it brought the dissolution of an empire. The Jesuits’ mission in China had never weathered this caliber of collapse, nor had they faced the perils of Marxist-Leninist theater. To better consolidate Party power, Mao reframed once discrete, peripheral issues into interconnected, life-or-death questions: religion, art, and even one’s level of educational attainment were cast as direct threats to Party power.

Luckily, Ladány grew up against the backdrop of another dissolving empire: Austria-Hungary. Before Ladány finished college, Hungary had undergone both the Red and White Terrors, and been ruled by fierce communists and anti-communists alike. So when he heard that Chinese Communist “People’s Courts” were closing in on his Jesuit counterparts, he was undoubtedly reminded of Hungary’s murderous revolutionary tribunals — and began taking precautions by moving south. Then in Shanghai completing his theological studies, the newly ordained Fr. Ladány migrated to Guangzhou and then Hong Kong, just a few months before Mao announced the founding of the People’s Republic. Seeing that Mao’s China was going to last much longer than the 133-day Communist takeover of Hungary, Fr. Ladány decided to commit his life to interpreting China.

Though we may not think much of a commitment like this today, before 1953 few took seriously the notion of China watching: McCarthyian America, preoccupied with rejecting the validity of anything “Communist,” dismissed anything red as propaganda. But Ladány’s firsthand exposure to Communist extremism in Hungary and China and training in Marxist-Leninist dogma — along with his ability to understand Chinese language, political culture, and economy — gave him a unique lens: he knew there were meaningful gesticulations of Communist Party narrative and intention behind its publications and broadcasts. Maintaining that CCP media could not be all but mere fabrications, on August 25, 1953, Ladány solidified his commitment to watching China and published the first of what would become some 1,200 newsletters: China News Analysis was born.

His thirty years of weekly (and later fortnightly) China watching point to a hope that we can understand and analyze China — not only properly, but accurately and in real time. His accurate estimation of those starved by Mao’s Great Leap Forward and constant reminders to keep an eye on Deng, despite what should have been three career-ending purges, only confirm the importance and applicability of his methodology. More importantly, his place as a patient explainer to both Western bureaucrats and the general public proves that, if we China watch well, relations improve.

It may not appear that good China watching results in stabilizing relations, as the bookends of the first twenty years of Ladány’s Cold War work were marked by the Korean War, two Taiwan Strait Crises, and the Sino-Soviet Split. But as we find ourselves closer and closer to a new Cold War, we ought to look to what stabilized our last bouts of Cold War free fall. Americans can be sure of one thing: free fall is slowed by Track I diplomats well-versed in their respective countries of expertise. Flipping through The Kissinger Transcripts or On China clearly shows that the analysts informing Kissinger’s strategy were uninfluenced by out-of-touch, Art of the Deal–esque politics. In other words, our last bout of Cold War free fall didn’t end with a splat in part because language-enabled experts like Ladány were delivering level-headed analysis to diplomats and policymakers.

As the Bamboo Curtain became more impenetrable, Ladány’s steadfast analysis earned him the trust of Chinese refugees, state intelligence agencies, and China watchers. We know that the methodology of Ladány’s China News Analysis influenced the China watchers of his day — indeed, he counted many embassies and consulates general among his subscribers. Declassified documents show that the consumption and application of Ladány’s methodologies were also used by US government actors who, like Ladány, sought to understand China in its own context.

The Failures of the US Media Landscape

When we think about Reform and Opening Up, our minds naturally gravitate to China’s markets and economy, but we rarely consider how radically China’s informational posture changed — not only under Deng but also since the internet and the iPhone. To be sure, there are thousands more China watchers today than there were in 1953, and accessing Chinese state media is much easier in this digital age than in Ladány’s. But what we’ve gained in quantity, we’ve lost in quality.

Understanding China in its own context — as Ladány did — demands decoupling from an amnesic media environment. Today, whether it is the origins of COVID, the imposition of the 2020 Hong Kong national security law, ongoing human rights violations in Xinjiang and Tibet, or developments in civil-military fusion — the American media complex fixates on what these issues mean for purely American interests, only within the context of a twenty-four-hour news cycle, and usually without being informed by China’s domestic media space. The above issues are all important and demand careful international scrutiny. But they cannot be meaningfully understood if China is treated as a monolith serving the media’s corporate, clickbaity purposes.

Most China coverage today fails on two fronts when it comes to honoring Ladány’s legacy: America’s media landscape is both unfamiliar with the Party’s primary source material and overly eager to label any nuance on China as unconstructive. If it doesn’t align with one’s own preconceived notions of China, it’s either Chinese propaganda or fake news from across the aisle.

Hard evidence of these media failures can be found in many US articles on China. A New York Times article covering the recent raid at Capvision, for example, files away the raid as yet another example of the “recent denunciation of the West by China’s top leader, Xi Jinping.” It’s interesting that the most caustic example of the West that Xi can conceive of, according to this article, is in fact Chinese professionals at a domestic Chinese company.

My colleagues and I also found soft evidence of this first failure when trying to publish an article about how China’s student visa bans had gone on too long. It eventually ran in The Diplomat, but only after facing rejection from many other mainstream outlets. As a special writer at The Wall Street Journal reminded us (and other outlets gave identical rationales),

Both the left and right see China as the enemy right now. The left for Xinjiang’s sake, the right for COVID’s — and here you come saying students ought to return to China and try to warm relations. I’m trying to think of who might agree with that sentiment and support a warming of relations. One doesn’t easily come to mind, but I’ll think it through further!

This failure continues to exacerbate an already-crippling negative feedback loop. If America’s China analysts cannot address China’s primary-source material, they inevitably rely on other China watchers to distill China for them. Narratives then develop and fixate on either small tidbits of dubious Chinese origin or on whatever the most popular prevailing distortion happens to be. Sometimes it means categorizing everything China does as a snub against the West. Other times it’s an abject unwillingness to publish articles that don’t further self-serving narratives of outrage.

A great meta-study underscoring the dangers of America’s broken media system can be found in Jonathan Haidt’s Atlantic article, “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.” Haidt argues that the US media system today rewards not productive debate, but those who cram a square peg through a round hole. This kind of issue-cramming is annoying in, for instance, American “culture war” contexts — but it is outright dangerous for the US-China relationship, especially given that military-to-military lines of communication aren’t open.

The Ladány Perscription

So, how might we make ourselves like Ladány? First, we might note that Ladány’s China News Analysis used only Chinese-language sources. Perhaps this practice seems like a stretch for today’s China watchers, but I think renewing a commitment to understanding China’s narrative may be the only chance America has at developing any nuance on China and rehabilitating the bilateral relationship. Second, we must treat CCP media as Ladány did: an object of genuine analysis — not merely as an instrument to buttress whatever the prevailing zero-sum narrative happens to be that day. We must read Chinese articles with “Chinese spectacles,” as Ladány once advised, and interpret these works as part of a whole Chinese-Marxist corpus, instead of just another tit-for-tat spat in US-Chinese relations.

This is no easy task. The Chinese language is hard. And if you thought understanding China’s news was any easier, Ladány himself remarks that the Communist press’s “misuse of words,” “misleading cliches,” and “impoverished … Marxist language make analyzing China ever harder for an unpracticed reader.” But its difficulty only underscores its importance.

We can still look to China’s primary-source material if we want to better understand how to anticipate and deal with current policy failures. Ladány’s unwavering commitment to revealing the truth behind the “impoverished Marxist language” supplied Track I diplomats with genuine talking points, informed by the Communist Party’s narrative. Dialogue today, on the other hand, has regressed so far that it would be difficult to find Track I diplomats who could describe, let alone explain, the genuine thrust or intentions of the Communist Party in its own context. If we want to build a floor, we must relearn how to talk to — not past — our Chinese counterparts.

Our federal foreign language deficit and desperation for Mandarin-enabled linguists and analysts are underscored by reports of gross overreliance on third-party translation contractors. While it is clear that those with a solid understanding of CCP history, Marxist-Leninist thought, and China’s political economy may be few and far between, they nonetheless exist. Few though they are, if China watchers continue to placate a dysfunctional media system, it will only result in more divergence between the track of engagement we envisioned under President Bill Clinton and the track we’re on today. Cold War–era ambassadors to the Soviet Union were appointed because they were Soviet experts who knew, spoke, and taught Russian. So if we’re honest about wanting to build a floor for this relationship, we should ask why we haven’t had a Chinese-speaking ambassador to China since 2011.

“We can’t think of anyone who might agree with a constructive sentiment” is no reason to hedge ourselves deeper into an already dangerous relationship. Perhaps the best way to end our currently floorless relationship is to review Ladány’s principles and get back to the basics of China watching. Analyzing Chinese-language source material, resuming robust student exchanges, and shaking up the US’s China diplomats to reflect a capacity for China — instead of assigning businessmen, career diplomats, and former Soviet specialists — are all good places to start. A relationship as complex and consequential as the US-China one requires this approach, lest we find this New Cold War much harder to navigate than the last.

For more on why investing in deep Party expertise is so important, see Jordan’s recent essay elaborating on why better research on China could help avoid catastrophe.

For the closest things we have to a China News Analysis today, see:

Manoj Kewalramani’s “Tracking People’s Daily” Substack, which features daily, close reads of the People’s Daily;

The Center for Advanced China Research’s weekly report on all things CCP;

The CCTV Follies series, an entertaining look at the evening news;

And of course, Sinocism.

Also do consider reading Simon Leys’s classic essay on Ladány. It runs as follows:

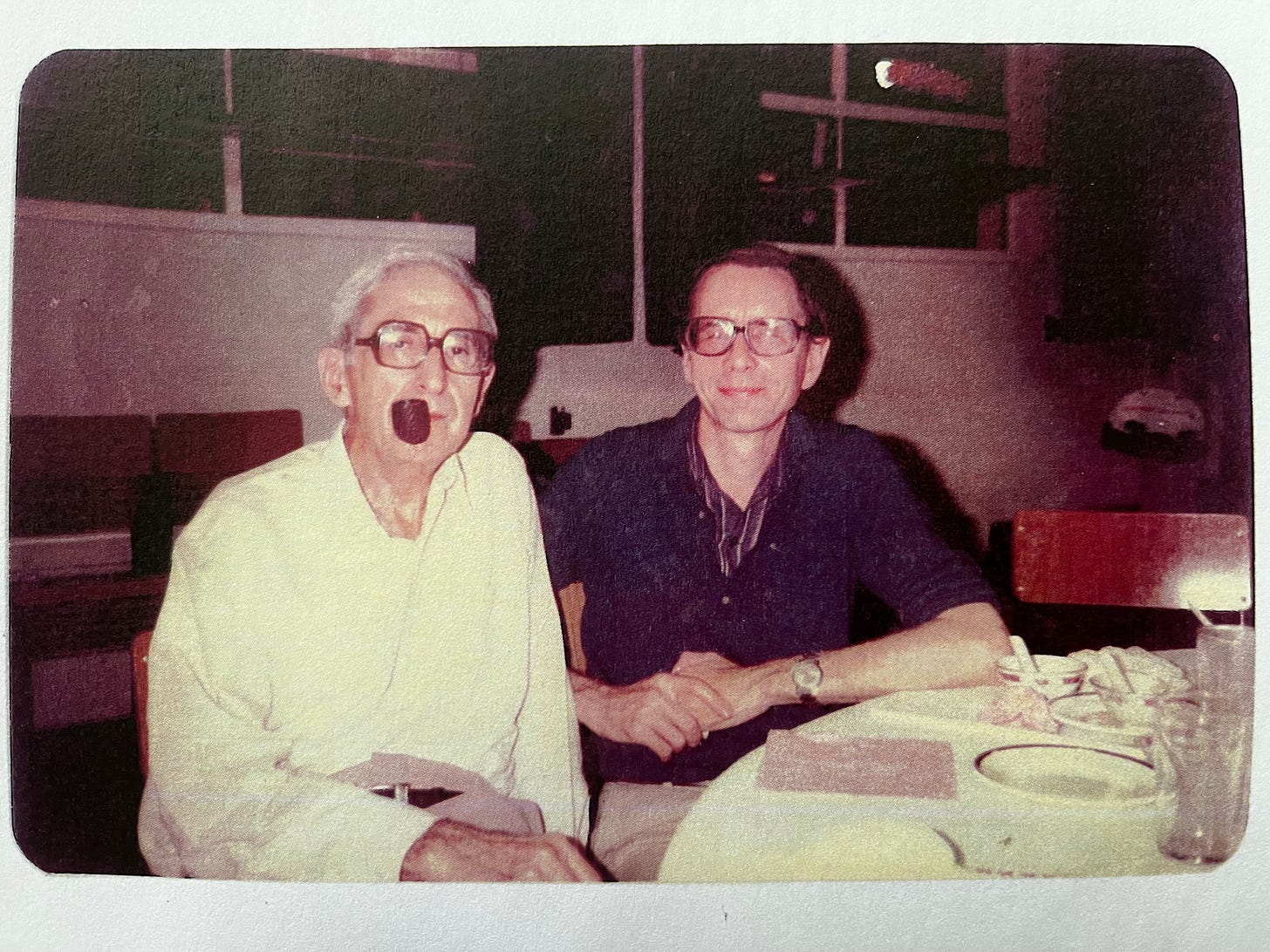

In any debate, you really know that you have won when you find your opponents beginning to appropriate your ideas, in the sincere belief that they themselves just invented them. This situation can afford a subtle satisfaction; I think the feeling must be quite familiar to Father Ladany, the Jesuit priest and scholar based in Hong Kong who for many years published the weekly China News Analysis. Far away from the crude limelights of the media circus, he has enjoyed three decades of illustrious anonymity: all “China watchers” used to read his newsletter with avidity; many stole from it—but generally they took great pains never to acknowledge their indebtedness or to mention his name. Father Ladany watched this charade with sardonic detachment: he would probably agree that what Ezra Pound said regarding the writing of poetry should also apply to the recording of history—it is extremely important that it be written, but it is a matter of indifference who writes it.

* * *

China News Analysis was compulsory reading for all those who wished to be informed of Chinese political developments—scholars, journalists, diplomats. In academe, however, its perusal among many political scientists was akin to what a drinking habit might be for an ayatollah, or an addiction to pornography for a bishop: it was a compulsive need that had to be indulged in secrecy. China experts gnashed their teeth as they read Ladany’s incisive comments; they hated his clearsightedness and cynicism; still, they could not afford to miss one single issue of his newsletter, for, however disturbing and scandalous his conclusions, the factual information which he supplied was invaluable and irreplaceable. What made China News Analysis so infuriatingly indispensable was the very simple and original principle on which it was run (true originality is usually simple): all the information selected and examined in China News Analysis was drawn exclusively from official Chinese sources (press and radio). This austere rule sometimes deprived Ladany’s newsletter of the life and color that could have been provided by less orthodox sources, but it enabled him to build his devastating conclusions on unimpeachable grounds.

What inspired his method was the observation that even the most mendacious propaganda must necessarily entertain some sort of relation with the truth; even as it manipulates and distorts the truth, it still needs originally to feed on it. Therefore, the untwisting of official lies, if skillfully effected, should yield a certain amount of straight facts. Needless to say, such an operation requires a doigté hardly less sophisticated than the chemistry which, in Gulliver’s Travels, enabled the Grand Academicians of Lagado to extract sunbeams from cucumbers and food from excreta. The analyst who wishes to gather information through such a process must negotiate three hurdles of thickening thorniness. First, he needs to have a fluent command of the Chinese language. To the man-in-the-street, such a prerequisite may appear like elementary common sense, but once you leave the street level, and enter the loftier spheres of academe, common sense is not so common any longer, and it remains an interesting fact that, during the Maoist era, a majority of leading “China Experts” hardly knew any Chinese. (I hasten to add that this is largely a phenomenon of the past; nowadays, fortunately, young scholars are much better educated.)

Secondly, in the course of his exhaustive surveys of Chinese official documentation, the analyst must absorb industrial quantities of the most indigestible stuff; reading Communist literature is akin to munching rhinoceros sausage, or to swallowing sawdust by the bucketful. Furthermore, while subjecting himself to this punishment, the analyst cannot allow his attention to wander, or his mind to become numb; he must keep his wits sharp and keen; with the eye of an eagle that can spot a lone rabbit in the middle of a desert, he must scan the arid wastes of the small print in the pages of the People’s Daily, and pounce upon those rare items of significance that lie buried under mountains of clichés. He must know how to milk substance and meaning out of flaccid speeches, hollow slogans, and fanciful statistics; he must scavenge for needles in Himalayan-size haystacks; he must combine the nose of a hunting hound, the concentration and patience of an angler, and the intuition and encyclopedic knowledge of a Sherlock Holmes.

Thirdly—and this is his greatest challenge—he must crack the code of the Communist political jargon and translate into ordinary speech this secret language full of symbols, riddles, cryptograms, hints, traps, dark allusions, and red herrings. Like wise old peasants who can forecast tomorrow’s weather by noting how deep the moles dig and how high the swallows fly, he must be able to decipher the premonitory signs of political storms and thaws, and know how to interpret a wide range of quaint warnings—sometimes the Supreme Leader takes a swim in the Yangtze River, or suddenly writes a new poem, or sponsors a ping-pong game: such events all have momentous implications. He must carefully watch the celebration of anniversaries, the noncelebration of anniversaries, and the celebration of nonanniversaries; he must check the lists of guests at official functions, and note the order in which their names appear. In the press, the size, type, and color of headlines, as well as the position and composition of photos and illustrations are all matters of considerable import; actually they obey complex laws, as precise and strict as the iconographic rules that govern the location, garb, color, and symbolic attributes of the figures of angels, archangels, saints, and patriarchs in the decoration of a Byzantine basilica.