Lithography — New Controls at the Tip of the Chip-War Spear

More export controls on ASML are coming. How will China respond?

Today’s breakdown is authored by “Lithos Graphien,” an anonymous contributor with decades of experience in the lithography industry.

Printed Electronics and the Age of AI

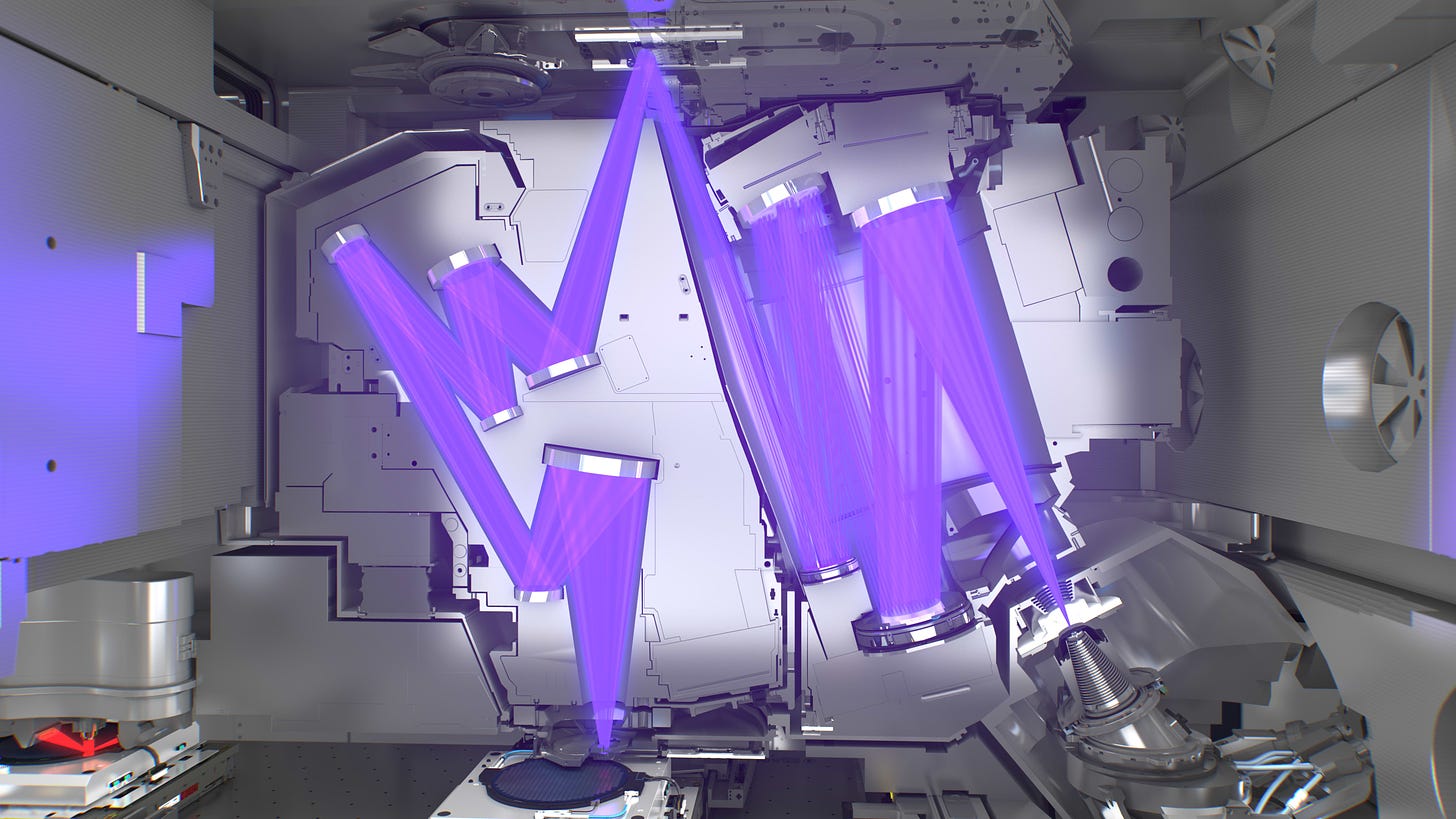

65 years ago, Robert Noyce of Fairchild Semiconductor envisioned a way to make complex electronics using a printing process known as semiconductor lithography. Thus, the monolithic integrated circuit — or microchip — was born.

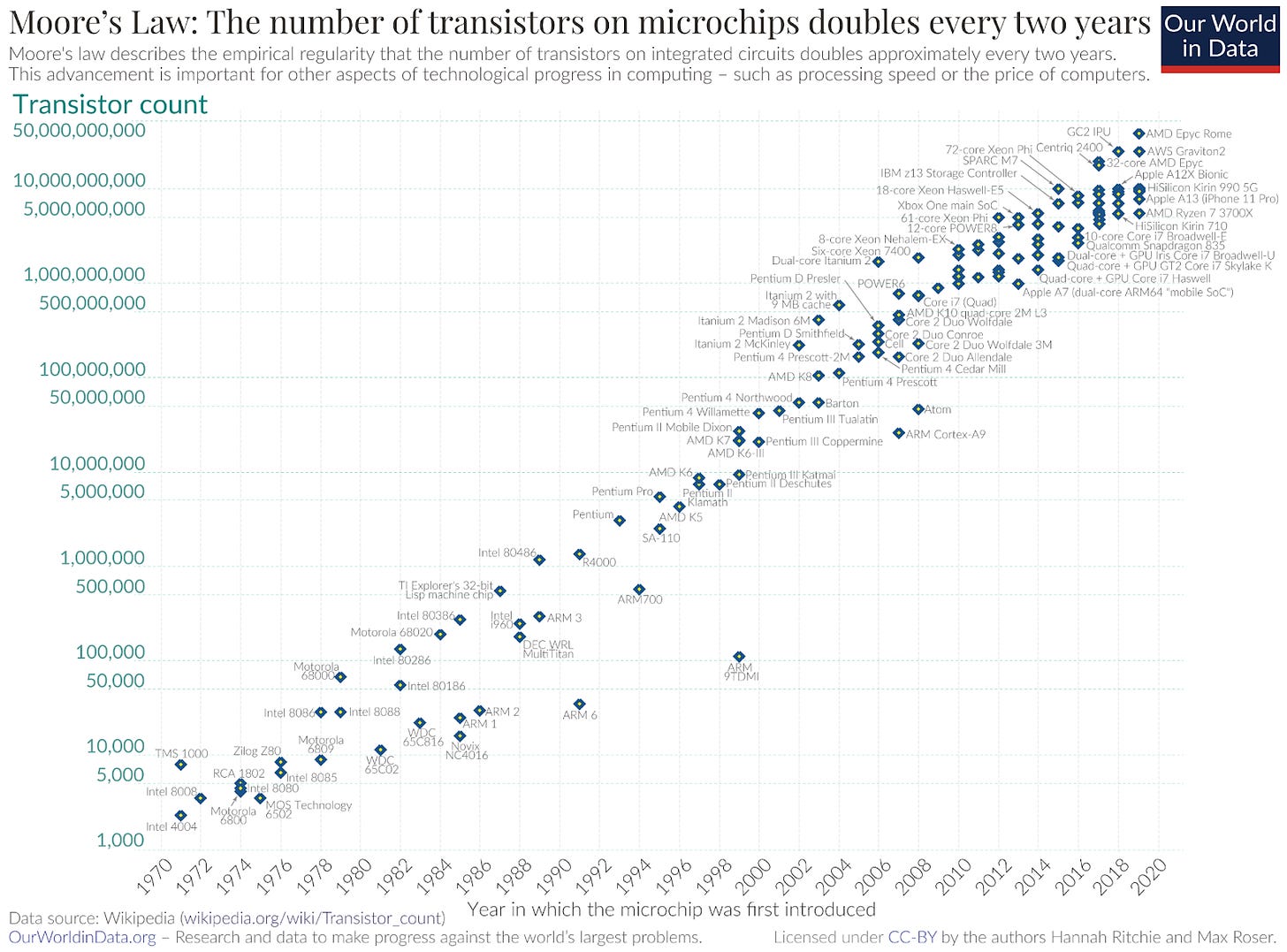

Not long after, Noyce co-founded Intel with Gordon Moore, who famously observed in 1965 that the number of transistors (electronic switches) on Intel’s microchips doubled every four years because of improvements in this printing process.

Moore’s Law holds to this day, with smaller and smaller circuit parts printed to pack more computational power into each new chip. In the near future, chips the size of your fingernail will contain an astronomical 100 billion transistors.

For this reason, a nation’s lithography capabilities determine the power of the semiconductors they can produce. That’s why lithography tools have been a key focus of US export controls.

Semiconductor Lithography Is at the Heart of the US-China Chip War

The US Department of Commerce — along with allies in the Netherlands and Japan — has so far issued two rounds of export controls aimed at limiting China’s lithographic capabilities. We summarized the first two rounds of export controls in this article.

Chinese companies like SMIC, however, have still managed to produce advanced semiconductors despite these controls. As another October approaches, which is Commerce’s favorite time of year to issue these updates, we can once again expect some type of action on lithography.

This week, confidential sources told Bloomberg that the Netherlands intends to let the export licenses for ASML’s scanner parts expire at the end of the year, bowing to pressure by US Commerce.

ASML is the leading provider of lithography tooling, and their most advanced scanners have already been banned from export to China. The problem, though, is that Commerce took a number of years to enact these restrictions, and a large fleet of advanced tooling is already installed in China.

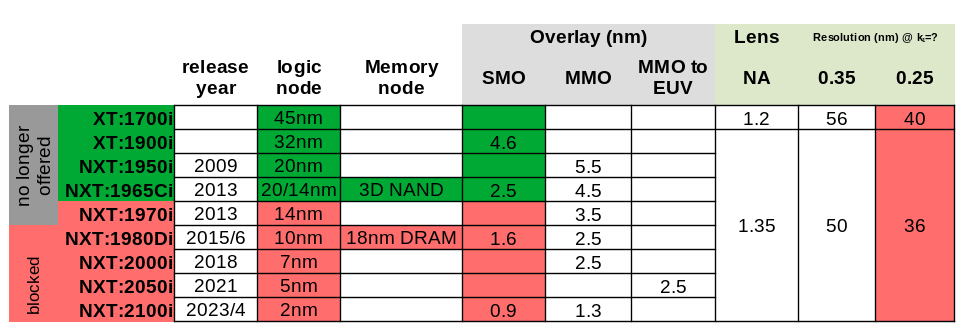

The chart below summarizes the machines made by ASML that are currently allowed or banned from export to China.

The key performance metric that Commerce uses to determine the law is called overlay — the ability of the machine to overlay two circuit patterns. Overlay is a measure of alignment error, and with today’s chip parts printing features on the tens-of-nanometer scale, overlay makes the difference between printing a mature node chip (>28nm) or an advanced one (<28nm). Each new generation of ASML scanners made incremental improvements in overlay.

Another improvement metric is throughput — the number of wafers per hour that can be processed through the tool. This doesn’t enable a new chip technology, but it has a considerable impact on the value of a scanner. Commerce has thus far made restrictions only on overlap, not throughput.

So what will happen next year for a Chinese fab using these tools?

First, note that no Chinese company can run these tools in secret. Every tool is accounted for by ASML and monitored by the factory. It should be fairly straightforward for ASML to segregate the export of parts for the blocked tools and the allowed tools. Most of the spare parts will be common between the blocked and allowed tools, so knowing where the parts are going will be key for enforcing the law.

Second, ASML’s immersion scanners are known for their reliability. They can often run for months at a time without maintenance, and for a much longer period before requiring a spare part.

These banned tools will be operational well into 2025 and perhaps beyond. But on a long-enough timescale, each of these tools will eventually become an idle boat anchor without spare parts.

So Chinese companies may attempt to stockpile key parts for these tools over the next four months.

Third, there is some confusion regarding whether ASML can or will block the servicing of these tools. The Dutch issue licenses only for physical goods, not technical services, so there is technically no expiration date on equipment servicing. Even so, it’s possible that ASML will stop servicing the banned tools anyway, because it’s in the spirit of what Dutch Commerce intended.

Uncharted Territory

The Dutch government’s move — letting export licenses for ASML’s scanner parts expire — at the request of US Commerce is unprecedented, in that Chinese companies legally purchased the machines under the assumption that ASML would support them for the lifetime of the tool. ASML still supports scanners they made thirty years ago. Impacted Chinese chipmakers will definitely respond through any legal channels possible. But if that fails, what is their contingency plan? What will ASML do to preserve revenues from their lucrative business in China?

The Nvidia model

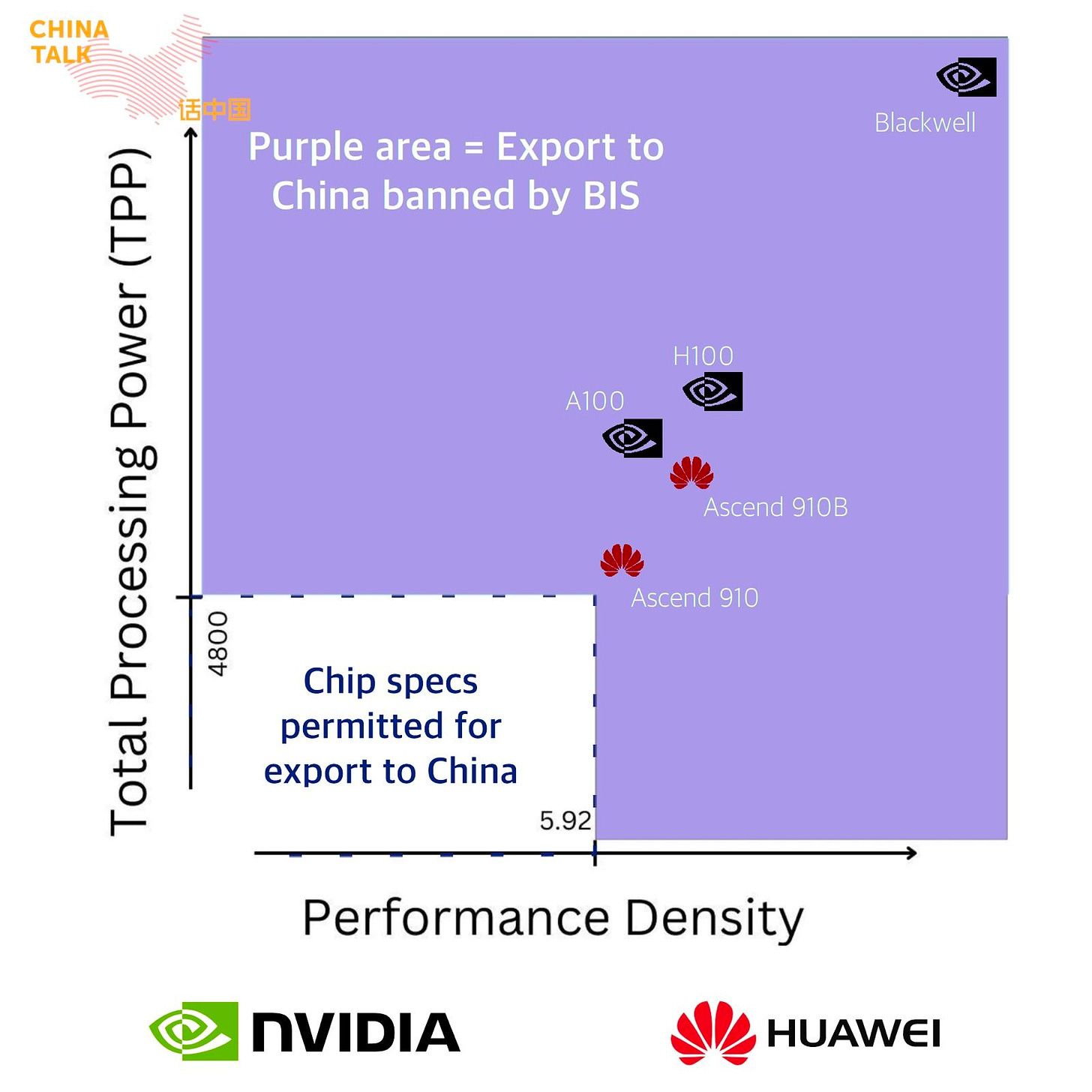

Nvidia has been the focus of US Commerce as well. To limit China’s AI capabilities, Nvidia’s GPUs are limited based on their performance specifications.

In response to each new Commerce rule, Nvidia designed a special chip for the Chinese market that met the throttle specifications. ASML can take a similar approach — ie. they can meet the requirements by throttling the overlay performance on a blocked tool inside China to the required value of 2.5nm SMO. That would be both in their interest and in the interest of Chinese chip companies.

How would scanner overlay throttling work?

Over the years, many of the overlay improvements in ASML’s scanners were driven by software. That could include a new correction algorithm or a way to take more measurements. For this reason, the most likely tool downgrade option will be a software update pushed out remotely from ASML’s factories. This accomplishes a few goals:

It’s a relatively cheap, fast way to keep China’s fleet of immersion scanners running and earning money. This will be important if the legal battles are drawn out over a long period of time.

In the event that Commerce relaxes some of the restrictions under a new administration, the performance can be updated to the new overlay targets to improve tool performance again.

The blocked tools have the added value of improved throughput — which is not under any restriction — to maximize tool value.

And the tool will retain its resale value to a customer outside of China. If SMIC wanted to sell them to TSMC, for example, a similar software update could return it to advanced performance.

What are the bigger implications for China?

These restrictions will make it harder for Chinese companies like SMIC to produce a 7nm or 5nm chip. Commerce’s intent to limit China at the 14nm node will likely be fully enforced. And without further policy intervention, China will likely accelerate production of mature chips, advancing toward becoming the world’s top producer.

Interestingly, Russia still has found a way to get ASML spare parts for its older machines – apparently mostly through China. https://nltimes.nl/2024/09/05/russia-using-old-asml-machines-make-microchips-weapons-report

I'm confused by how software restrictions would work. China would have people capable of twiddling bits and restoring performance. Even with a complete secure boot solution this feels like more of a speedbump than a roadblock.