Luckin Coffee a "National Humiliation"

This week’s ChinaTalk podcast featured a new format called ‘Coronastories’ which shared listeners’ reflections on their experiences across Asia over the past three months. If you have an audio diary of your experience you’d like to share, just reply to this email.

This article first appeared in Technode.

After Luckin admitted to falsifying sales data, a lot of English-language coverage has covered jokey Chinese-language commentary claiming the company is now “a charity to buy China coffee.” But the discussion about Luckin in China goes a lot deeper. Other Chinese-language viral articles provide deeper reflections on business culture and regulation in China.

A piece by independent, Hong Kong-based, finance-focused personal WeChat channel Qin Xiaoming titled “Luckin Coffee, Our Nation’s Shame” focused on how many Chinese investors lost money from the fraud:

The ultimate source of much of the money invested in China stocks is still China. Because China has a more intuitive understanding of these companies operating in China, the first choice for many domestic investors investing in US stocks is Chinese companies listed in the US. When I traded US stocks in the early years, I bought all the major Chinese stocks. Does that make my money “capitalist” or “socialist”?

Luckin Coffee was a capital scheme. Of course, someone will eventually pay the price. It’s just that the person who pays the bill may not necessarily be the one most in the position to.

A company that does not hesitate to engage in fraud is not something to be proud of, but can only be considered a national shame.

Another independent anonymous WeChat account lamented just how out of touch sell-side analysts at Chinese firms are:

The report Muddy Waters publicized [editor’s note: The report was published anonymously] wasn’t afraid of seeking truth from facts. They employed 92 full-time employees and 1,418 part-time contractors and took 11,260 hours of surveillance video.

And those of us "professional" analysts, those who were still writing reports to promote Luckin Coffee up until the last minute, how do we do our research?

We go to the company, watch a PowerPoint in a fancy conference room, chat with the CEO, CFO, the secretary of the Board, and the “management,” talk to each other, add some people on WeChat, send around red packets, ask for guidance, and go back to adjust our models.

Maybe we do some “expert research”: pay the likes of GLG [a firm that connects investors and researchers with experts]. Talk to a few so-called industry experts over the phone, ask unprofessional questions, and get unprofessional answers.

We might do some grassroots research by downloading an app for a few days or buying a product a few times.

We participate in industry exhibitions, but most of the time we’re not really talking to people in industry but chatting with our friends and posting photos on Wechat.

Recently I met with the boss of an Internet company. The first thing he said was: "I am particularly dismissive of A-share analysts"; I was very ashamed, and then the second sentence he said was: "I actually think analysts of foreign-listed companies are equally garbage.”

Tsinghua Finance Professor Xuan Tian, who did his PhD and taught for years in the US, said Luckin Coffee should be a lesson for A-shares markets to consider reform along American lines.

The market in Mainland China lacks a mature short selling mechanism (the only stocks that can be subject to margin calls are the Shanghai and Shenzhen 300 constituent stocks, and the amount of securities that can be borrowed is very small). Short sellers rarely ever get involved.

This is not to the advantage of China’s capital market. On the contrary, the lack of a short-selling mechanism has kept A-shares for the past thirty years in a state of infancy.

Based on the current status of China ’s capital markets, are there effective laws that can restrict the fraud of enterprises and intermediaries? In contrast [to the US], we have no class action system, and even if the new securities law is officially implemented from March 1 this year, the punishment for fraud is still rather "gentle.” Those who have not yet issued securities are subject to a fine of more than 2 million yuan but less than 20 million yuan; if securities are issued, a fine of not less than 10% of the amount of funds raised illegally shall be imposed. Compared with before, such punishment has become more significant, but it still cannot achieve the effect of deterring fraud by listed companies. Once the company is listed, the money it has in hand can reach more than 1 billion yuan, so compared with a 2 million yuan fine the penalty is almost negligible (according to the data of 198 companies listed in 2019 and financing of nearly 250 billion yuan, the average initial financing of each company reaches 1.26 billion yuan).

As for domestic capital market regulators, I suggest that we should take a hard look at our own regulatory status and learn the lesson of Luckin. By drawing on the strict regulatory system of the US capital market (such as its class action system, huge fines for companies, and criminal liability for individuals who violate serious laws and whistleblowers protections and payouts), we can increase the cost of corporate financial fraud to help us better improve the quality of listed companies and protect the rights of small and medium investors.

Finally, an anonymous Shanghai-based account described the evolution of sketchy business models in the VC space, condensing the whole Luckin story into two paragraphs:

It is said that the most popular business model is not 2B (for enterprises) or 2C (for consumers), but 2VC (for venture capitalists). Many entrepreneurs racked their brains to think about a project quickly and sell it to VC at a high price. In the end, if the products and services provided by this project cannot create value for customers, customers will not pay, and VC will not make money. VCs aren’t that stupid.

So there is an upgraded version of this paragraph, saying that the most popular business model now is not 2C, nor 2B, but 2SB (“傻逼” or “stupid fools” in Chinese). The VCs who invested knew that it was impossible to make money when investing in this project, but as long as it was hyped, someone could take the money and he would be able to make money.

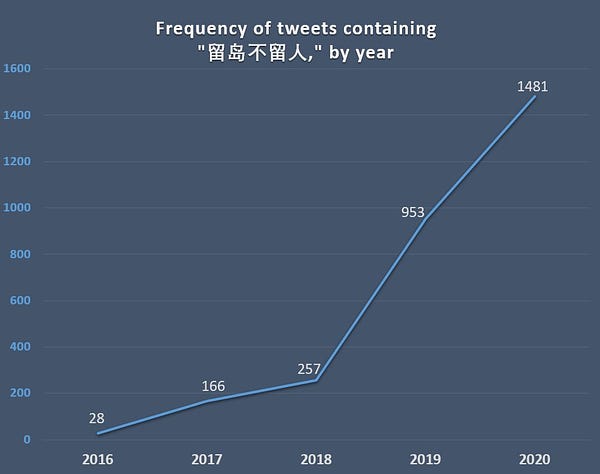

China Twitter Tweets of the Week

Yes, we do Gossip Girl and numismatics here at ChinaTalk…

Thanks so much for reading and stay safe everyone.