Makers of Modern Strategy with Hal Brands

Standing on the shoulders of giants

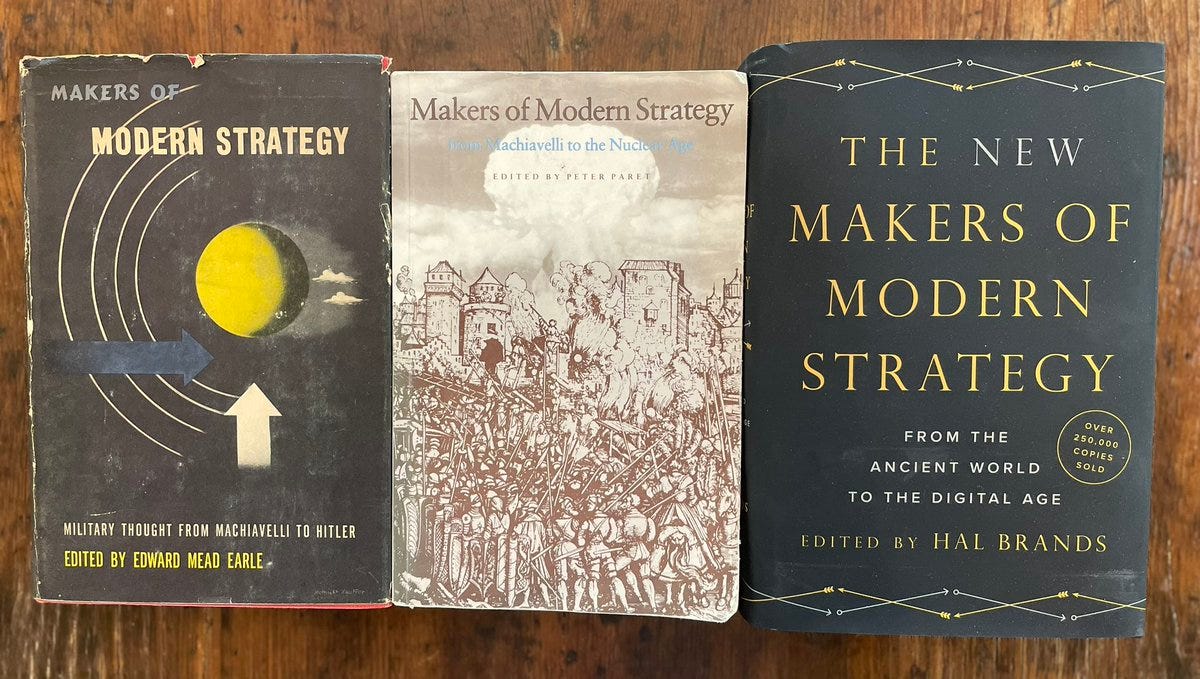

Few books have influenced me as much as the Makers of Modern Strategy series. The three volumes (published in 1942, 1986, and 2023) are indispensable to understanding statecraft, leadership, and the evolution of warfare across millennia.

The New Makers of Modern Strategy (2023) is a thousand pages long and analyzes strategy from ancient Greece to the Congo.

The man behind this behemoth collection is Hal Brands, a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and a returning ChinaTalk guest.

In our conversation, we discuss:

The process for compiling such an ambitious collection of essays;

Unique insights and new topics covered in the 2023 edition, including Tecumseh, Kabila in the Congo, and Strategies of Equilibrium in 17th Century France;

Advice for reading the book effectively;

Revolutions in military affairs, from the atom bomb to quantum computers.

For reference, you can compare the content of the three volumes with this spreadsheet, courtesy of Nicholas Welch.

Have a listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.

Favorite Essays

Jordan Schneider: Hal, thanks so much for producing this book.

Looking back at the process, which essays were you the most excited to publish?

Hal Brands: That’s a little bit like asking me which of my children I’d prefer to keep. They are all beautiful and they are all my favorites. There were maybe a handful that are worth mentioning just because, from the beginning of the project, I thought they were going to be really cool.

The first substantive chapter is an essay by Sir Lawrence Freedman, the great British scholar [Ed. Coming soon to ChinaTalk!]. He is the only scholar who wrote an essay in the 1986 version and in the 2023 version. His essay is called, “Strategy: A History of an Idea.”

It illustrates how definitions of the terms “strategy” and “strategist” have changed over time. I had Freedman in mind when brainstorming ideal authors to write that essay, and I was just delighted that he could do it.

Another interesting angle on a classic subject is Hew Strachan’s essay on Clausewitz. Carl von Clausewitz has been a recurring character in both the 1943 and 1986 editions of the book. He looms over the field of strategic studies.

But Strachan’s interpretation is basically that everybody gets Clausewitz wrong. Michael Howard’s translation of Clausewitz — which all of us professional nerds have read and relied on — is actually a distortion of Clausewitz’s argument about the relationship between war and politics.

When you get Hew on board to do an essay like this, you know he’s going to say something profound and you know he’s going to say something original. I was even a little surprised by just how jarring that reinterpretation was. It’s really going to make a splash.

Jordan Schneider: I’ll shout out two more essays that I really enjoyed — one was the Tecumseh essay. For our non-American listeners, Tecumseh was a Native American leader and war hero who banded during the War of 1812 between the US and the UK. He came pretty close to beating the US and shutting down Western expansion.

Tecumseh pulled together a larger fighting force than any other American Indian chief in history, creating a twelve-hundred-mile barricade to limit westward expansion of the United States…

[H]e propagated centripetal religious beliefs that advanced political power within tribes and encouraged accession to the Confederacy; he used social suasion to reduce reliance on colonial-produced goods; he won foreign economic support that freed up fighters for military campaigns; he secured consequential European military involvement; and he produced an organized military force capable of defeating the US militarily.

The Shawnee Confederacy threat precipitated the doubling of the size of the US military, and the Confederacy imposed the largest combat losses the US had known to that point.

The United States government defeated this elegant strategy not on the battlefield, but economically.

[The New Makers of Modern Strategy, pp. 369-370]

The other essay that completely blew my mind was Jason Stearns’ “Strategies of Persistent Conflict,” which looked at the Congo wars. The logics of persistent and brutal conflict is different from the military strategies described by Clausewitz and Jomini.

Having those modern wrinkles added to the canon was really interesting.

Hal Brands: Those were two of the most original essays in the volume, both in terms of the subjects and also how they compel us to rethink strategy. The thesis of Kori Schake’s essay is that Tecumseh was really a practitioner of what we would consider an all-of-society strategy. As you mentioned, he came close to succeeding.

Jason Stearns wrote the essay on wars in Africa. That one is so interesting because it turns the traditional Clausewitzian paradigm on its head, pointing out that protracting the war can be a form of strategy. Not in the Fabian sense of trying to exhaust your enemy and then defeat him, but in the sense that the war may actually be profitable for the groups undertaking it — continuation of the war can itself be a strategy.

[I]n the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), as well as in other weak states…waging war becomes both a lifestyle and a fundamental tool of political survival, providing a means of managing dissent and doling out patronage…

It was during this stalemate of [The Second Congo War] that… [t]he assorted belligerents became deeply invested in various forms of economic activity, a blend of racketeering, extortion, and taxation. …

Following the blueprint for United Nations peace processes at the time, diplomats pushed for peace talks, which they hoped would be followed by a power-sharing agreement and the reunification of the country. …

Some scholars go so far to argue that the penchant for power-sharing agreements by Western donors has inadvertently incentivized rebellions by making them an acceptable path to power and lowering the cost of insurgency. While this finding is contested, it is clear that international norms against protracted military conflict have made it more difficult to achieve military victories. …

The war made large-scale agricultural production almost impossible, cutting off trade routes to the rest of the country, pillaging livestock, and preventing investment. The economy became increasingly focused on the mining sector, which in turn became extremely militarized. Meanwhile, employment opportunities shrank for the youth, making armed insurgency more attractive.

[The New Makers of Modern Strategy, pp. 1048-1050]

Jordan Schneider: There’s something that’s so dark about this entire book. I catch myself getting excited as I flip through this book trying to choose which essay to read. “Maybe it’s time for Napoleon. Maybe it’s time for nuclear war.”

These are exciting topics, but it’s also tragic that as a species we have spent so many thousands of years innovating new ways to kill our fellow humans. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Hal Brands: You put your finger on an important point, which is that the content of strategy changes in different eras as different technologies and different challenges emerge. The basic practice — the nature of strategy — doesn’t change that much over time. It’s really about trying to use the means at your disposal to achieve whatever aims you seek, in the face of all the resistance and chaos of the world.

Even though it’s something that exists in peacetime as well as wartime, we most frequently pay attention to strategy when the stakes are high. That’s typically when violent conflict is either happening or threatening to happen. There is an inherently dark nature to the subject material.

As I often point out in my writings or when I’m talking to students — strategy is itself a very optimistic endeavor, because the idea of it is that you can impose a certain purpose on events rather than simply being tossed around by them. You can use power in purposeful and coherent ways. That’s the enduring challenge of strategy, and that’s the thing that pretty much everybody featured in this volume was wrestling with in one way or another.

The History of Security Studies

Jordan Schneider: Let’s take a step back then and look at this concept of security studies. Do you want to talk about the origins of this as a pseudo-discipline and how the first book ended up coming together in 1943?

Hal Brands: Absolutely. I’ll make a point here that’s a little deep into the academic weeds, which is — there’s often said to be a difference between strategic studies and security studies.

Strategic studies, to put it bluntly, is the study of political-military issues. It’s got a somewhat narrower thrust. Security studies can encompass all sorts of things. There are various different types of security. It can deal with climate, it can deal with human security, it can deal with a whole range of issues. It’s typically thought of as a somewhat more capacious discipline.

In my mind, they’re very closely related. People who are involved in one camp or the other will say they are different things. That distinction is just worth mentioning for CYA on my part.

The development of Makers of Modern Strategy is inseparable from the emergence of strategic studies and security studies as related fields in the United States. The first volume of Makers, as you mentioned, was published in 1943, it was started a couple of years before that. The editor was a guy named Edward Mead Earle, who was at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. He had really been involved in a rethinking of the requirements of national security as the world fell apart in the 1930s.

He was a big proponent of the idea that the United States needed a more coherent approach to grand strategy, bringing together all the different forms of national power to deal with all of the threats — economic, military, ideological — that emerged as fascist regimes gained the ascendancy during the 1930s.

He was motivated to pull the book together by the idea that the United States was henceforth going to be far more deeply and far more consistently involved in global affairs than it had been in the past. The American people — not just national security elites but just educated men or women on the street — needed a deeper understanding of military affairs and strategic affairs more broadly if the United States was going to have the educated citizenry it needed to be effective in this era.

That was the goal of the first volume. It developed in parallel to the emergence of strategic studies research and teaching programs. It was part of the development of the intellectual sinews of the American superpower during the late 1930s and 1940s. It was a smash hit.

Jordan Schneider: The idea for this book was great from the start, but it took money to fund the professorships and create the conferences to entice more academics into grappling with those questions of national power and grand strategy.

The book and the broader thinking that this field generated, which ended up informing a lot of how America has engaged with the world for the past 75 years, wouldn’t have happened without that initial academic seed funding sorts to allow people to research and write along the lines that he initially laid out.

Hal Brands: That’s exactly right. Ideas may be cheap, but good ideas aren’t cheap. Developing a cadre of intellectuals who are going to work on major research projects — that takes money. The emergence of strategic studies as a field was led by Carnegie and a couple of other foundations and philanthropic entities.

Then, of course, the field really develops in the context of World War II and the Cold War, when also the US government is throwing more money at these areas than ever before — including by funding the RAND Corporation.

You wouldn’t have gotten security studies or strategic studies as fields in the United States without the collapse of the international system in the 1930s, the interest that spurs in these sorts of issues and then the investments that philanthropic entities in the US government make in it over the decades to follow.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on this 1943 book. It is a fascinating document, because it’s literally in the middle of the war. You have essays by Earle talking about Hitler’s strategy and he’s like, “Yeah, we think they’re going to lose, but we’re not sure.”

There’s another essay about Stalin where the author is like, “Yeah, we’ll see about this spring offensive.”

There seems to be a lot of personality in the authors where they can show their prejudices on their sleeve. Everyone’s just making fun of Erich Ludendorff for being an idiot. Looking at that book, what stuck out to you about those essays?

Hal Brands: As you mentioned, a lot of the essays were written really without knowing how the war was going to end. The essay on Hitler makes the point (which in retrospect was true) that Hitler was a better strategist before the war began than he was after the war began.

The book was published in 1943, so it was probably completed in 1942. This was at a time when the outcome of the war was very much in doubt. For long stretches of 1942, it seemed plausible that the Axis might be able to, if not win the war, at least push their conquest to the point where winning it would be extremely difficult for the Allies. It was history written in real time, which is hard. That’s one thing.

The second thing is that the composition of the contributors is very much a product of the moment. If you go through and you look at the biographies of the people involved, a number of them were essentially refugees from Hitler’s Europe. They were European academics who’d been pushed off the continent by Nazi conquests and then ended up in the United States where, of course, they enriched the intellectual life of this country as well.

Then, the third point is that the contributors were very much aware that this was not a value-free exercise. They were not necessarily taking a god’s eye view of the international system.

Of course, they were trying to be objective and dispassionate in their analysis of history, but the point of the book was to help democratic societies do strategy better. This was not disinterested history. This was history with a commitment to helping democratic societies survive and flourish in a very dangerous world. That ethos has survived in the succeeding volumes.

Jordan Schneider: This idea of new history as a stimulus to action, with this book aimed at everyday concerned citizens, and not necessarily scholars of Jomini — that’s what makes this book so fun for nonprofessionals or students to flip through. The best essays make you want to buy a book about the topic because you’re interested in learning more.

There are so many little gems in these sentences and paragraphs that both try to teach you a lesson about the essentials of these stories, but also really end up enticing you to want to learn more.

One example from the essay on Delbrück, the military historian. He was this German guy who was the first one to actually try to count up how many people would have been at a Roman legion — for example, was Caesar exaggerating when he said he was fighting against 500,000 guys.

Hal Brands: It helps that the essays, particularly in the first volume, are about people. There’s something relatable about essays that are about people. That’s the thing that will draw in the folks who may not be academic experts on Jomini, but are just interested in military affairs and interested in strategy and interested in reading interesting things. That was part of what made the first book such a success. I know it’s part of the appeal of the book still.

The other nice thing about the first volume, by the way, is that the essays are all relatively short. They’re punchy. They get to the point. When I was putting together this volume, that was one of my goals, to make sure that the essays were meaty but didn’t go on forever and ever.

Jordan Schneider: There’s an essay on Hitler that essentially says, “We shouldn’t forget that Hitler is a genius.” It argues that the way he was able to pull off the 1930s is something that deserves praiseful discussion in the context of a grand strategist. That really stuck out to me, and it must have made quite the splash in 1942.

Let’s turn to the 1986 version of this book. What stuck out to you about that one?

Hal Brands: It’s an interesting book, in part because it took so long to do. The first discussion about updating Makers really started to happen in the 1950s. There were a bunch of different attempts to get a second volume, and various false starts involving various historians. It took 40+ years for the thing ultimately to come together.

What’s interesting to me about the second volume is that it’s written in light of the dangers of war in the nuclear age. Nuclear weapons create an element that were not there when the first Makers was published. That is reflected in the Lawrence Freedman essay in that volume that’s about the nuclear revolution and the schools of strategic thought that are associated with it.

It also hangs over a bunch of the essays in other ways. It’s there in terms of discussions of Clausewitz. It’s there in terms of just thinking about how high the stakes of war in particular have gotten and how important it is for people to understand what goes into good strategy in war.

In some ways, what’s also interesting about that book is that the definition of strategy changes from volume to volume. The definition of strategy in the first volume is very broad — it’s essentially what we think of as grand strategy, all elements of national power to achieve some important objective.

The definition of strategy in the second volume is narrower. It’s more closely related to military affairs and political-military affairs than it is to the larger conception of strategy. The nuclear revolution and the shadow it cast over all war and all statecraft in the second half of the 20th century has something to do with that.

Jordan Schneider: It’s weird that WWII ended two years after the first edition was published, and then the Cold War wraps up three years after the second one was published. I don’t know if there’s some leading indicator here.

Hal Brands: Maybe we’ll win it all in 2025 or 2026. Look out, Xi Jinping.

Project Management and Long Haul History Research

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss the newest edition. How does a project like this come together? Does Princeton University Press just call you up? Was there an interview process?

Hal Brands: There is a long story of how this volume came together that will be of interest only to me and my immediate family members. The short version is that Princeton had been thinking about doing a third edition because it had been 30+ years since the second volume.

It was clear that we were entering what would have been referred to in 2017 and 2018 as “the new era of great power competition.” A lot of the questions about nuclear strategy and long-term rivalry that had gone into abeyance with the end of the Cold War were coming back in a very serious way.

The editor of Princeton, Eric Crahan, came down to Washington and had a conversation with me and also with a couple of friends who were involved with the project. Then, for a variety of reasons, mostly pertaining to other personal commitments, couldn’t follow it all the way to the end.

We put together — in conversation with Princeton — a proposal for how to structure the book. The final product looks something like that initial proposal. The idea behind it was to do a book that would be richly historical like the other two volumes, but where the choice of topics would be relevant and would be recognizable to people grappling with challenges of US-China rivalry, nuclear deterrence, and the other issues of today.

Jordan Schneider: As you were going through that back catalog, what were the ones that you thought you couldn’t do without, and how did you decide to cut other subjects?

Hal Brands: Well, certain things are just so fundamental to an understanding of strategy that you really can’t do without them, especially if the idea is for this volume to stand on its own. You can read this volume without having already read volumes 1 and 2.

There’s a fair amount of overlap. Although all of the essays are new and original, when the book covers what’s called foundations and founders, basically, these aren’t the greatest hits of strategy, going back to Thucydides and the Peloponnesian War, Machiavelli, Clausewitz, and so on and so forth.

In each of those cases, the people who wrote on those subjects put really interesting new twists on the subject. I’ll call out Matt Kroenig’s essay on Machiavelli, which is actually quite original and quite interesting.

One of the real goals of the volume was to bring stuff up to date. Even though the 1986 version was written under the nuclear shadow, there were only four, maybe five essays that really dealt in detail with post-1945 issues. By the time we did version 3, obviously, we knew how the Cold War had ended. There was an entire generation of great scholarship on the Cold War. There is a whole section of 9 or 10 essays on Cold War-era stuff. Then there’s a whole section on post-Cold War content, because the post-Cold War era was 30 years old by the time the book was in gestation.

There’s much more of an effort to renew our understanding of strategy, not just through the greatest hits again, but also by looking at newer subjects that hadn’t been covered by earlier volumes.

Jordan Schneider: My favorite direct take on China is actually a riff-off of an old essay. It’s called “Economic Foundations of Strategy” by Jonathan Kirshner and Eric Helleiner. Instead of doing just Smith, Hamilton, and List, it was beyond Smith, Hamilton, and List. There was this really fun comparison between Chinese thinking and Western thinking in the late 19th and early 20th centuries about what kind of economy you needed in order to be a great power.

Hal Brands: I’ve got to give a shoutout to the two authors of that essay. Jonathan and Eric can take credit for that twist on the original. I went to them with a more conventional idea of an essay on the economic foundations of strategy. They asked if they could do something totally different, and it ended up being much better than what I had in mind.

Jordan Schneider: Did you start with a topic and then find an author, or did you start with the authors and then find topics? How did that matching process end up working for you?

Hal Brands: It’s a mix of both. There are some people who are so brilliant and so established in the field that you know you just have to have them in the volume. Basically, I would have let them publish their shopping list if they had offered to do that. I was going to have Lawrence Freedman in this volume no matter what he wanted to write. I was going to have John Gaddis in this volume no matter what he wanted to write.

Then, there are some people who you know are experts on a certain topic. You go to them and you ask, “Could you write on thing X?” Liz Economy has written — for my money — the best book on Xi Jinping’s China. I approached her and asked if she would write on that, and she very graciously agreed.

Then sometimes, you’ll take a proposal to someone and say, “Could you write on subject A?” They will say, as was the case with Jonathan Kirshner and Eric Helleiner, will say, “Well, why don’t I write on this other thing instead?” That happened in a few cases and it invariably made the volume better.

Jordan Schneider: That essay was excellent, bringing the legalist Sun Yat-sen and Albert Hirschman together into one argument. I can see how that wasn’t just an idea you pitched to them right out of the gate. It’s interesting how that editorial give-and-take works.

Hal Brands: There were a bunch of essays where that was the case. There’s an essay on the origins of the laws of war in the 19th century where I went to Wayne and asked him to do something more conventionally, came back and pushed back.

That creative tension or the give and take is actually one of the most interesting parts of an edited project because the people who you are recruiting to write these essays know far more about the subjects than I do. They’re typically a better judge of what’s interesting and what’s new.

Jordan Schneider: I’m curious, did they feel they had to bring their A-game? This is The Makers of Modern Strategy. This isn’t any essay collection.

Hal Brands: I will say this — I had far less trouble rounding up writers for this than you often do with edited collections. Let’s be honest, there’s not a huge professional payoff for writing essays for edited collections, in general.

But this is a special volume. It has been the authoritative text in strategic studies for 80 years, as you’ve pointed out. It’s a compendium of some of the greatest scholars in the field over a few different generations. I was hoping that authors would be excited about signing up for it for that reason — because I certainly couldn’t pay them enough to make it rewarding in a pecuniary sense.

I was just delighted that the vast majority of the people that I approached were willing to do it. The vast majority were excited about doing it. This is the thing that was really, really amazing. The vast majority turned in their essays in good shape and on time. I don’t say that because I wasn’t expecting good work from these people — they’re all stars. But, man, that’s usually hard when it comes to edited collections.

Jordan Schneider: There is a very cool intergenerational dialogue that is going on here. You’ve got contributors in their 80s and you’ve got contributors in their 30s as well. Aside from topic diversity, were there other diversities you were trying to build into this collection?

Hal Brands: There are a lot of different dimensions of diversity here. You mentioned one of them, which is that within this volume, we have two, maybe three different generations of scholars. At the more senior end, you have somebody like John Gaddis who’s been writing about strategy literally for half a century and does it as well as anybody else and just has an unparalleled knowledge of the field.

You have folks who are in the middle. Frank Gavin, my colleague at Johns Hopkins, who is certainly one of this generation’s preeminent extroverts on nuclear strategy, has written a couple of books about it and lent his expertise to this endeavor.

Then, you have younger folks as well. That includes Carter Malkasian, author of the best book on the US war in Afghanistan and one of the top scholars of the post-9/11 wars more broadly. Charlie Edel, who’s roughly of my vintage, wrote about John Quincy Adams.

There are some folks who I think view strategy in the more traditional sense in this volume, as essentially a political-military issue. Then, there’s somebody like Jason Stearns — I don’t know if he thought of himself as a scholar of strategy before he wrote this essay, but he brought a really interesting perspective on how strategy works in modern wars in Africa.

Jordan Schneider: How do you recommend people read the book?

Hal Brands: I recommend that people start by reading the opening essay, which is by me. This isn’t just self-flattery — the opening essay helps contextualize everything that’s going to come and try to piece together some of the common threads that you can pull across 45 different essays. I’d highly recommend that they read Lawrence Freedman’s essay which explains how our understanding of strategy has evolved over time.

Then, I’d say they should read about the things that most interest them. This isn’t a book where you have to read all 1,168 pages. You can get something out of it by reading the six or seven essays on the subjects that most concern you.

Then, I’d also recommend reading an essay or two that you wouldn’t normally read, that’s outside that six or seven. That’s actually where you’ll get new insights about strategy. If you read about Mao Zedong as a strategist, or if you read about the post-Meiji generation in Japan, or you read about Soleimani and Gerasimov or whatever the case may be, even if that wasn’t what got you interested in the book in the first place, there’s a payoff there because it’ll push you to think about strategy and how it’s practiced in different ways.

Jordan Schneider: For me, the least interesting essays were the China ones, which may be the same for a lot of the listeners of ChinaTalk. Thinking about China in the context of all these other essays and historical case studies was more rewarding in my opinion.

Hal Brands: All of the essays were chosen because they had something to inform our understanding of problems in the present. It could be that if you read a strategy about long-term competition — as seen by Jackie Fisher or Andy Marshal — it gives you some leverage on thinking about the US-China relationship today even though that’s not what the essay is really about.

It could be that an essay on the dynamics of multipolar rivalry in the early modern European system gives you some purchase on the dynamics of diplomacy in our current era. This is meant to be a book where you can find the relevance in pretty much any essay you read, even if the parallels aren’t directly drawn. You want the thing to stand on its own. You want people to be able to profitably read it 10 years from now, but it should also speak to the problems that people have in mind when they dip into a book like this.

Jordan Schneider: That’s an interesting way to read it — read the essays you’re interested in, but also read the essay that seems least interesting to you. For me, I gotta say — the title of the essay “French Strategies of Equilibrium in the 17th Century” didn’t necessarily do it for me. But there is some cool stuff in there! These are total weirdos. It’s a really different context, but also not 100% different, because it’s still people, it’s still states, and they’re still subject to their own constraints and opportunities.

Hal Brands: There’s that one, which is a great example of something where the relevance may not be immediately significant when you read the title. As you get into it, there is deep significance for understanding the challenges we face today.

You already mentioned the essay on Tecumseh where that’s the case. Mike Morgan, who was a professor at UNC Chapel Hill (and also happened to be my grad school roommate) has an essay on ideal politics or strategies of liberal transformation, how people have thought about the role of liberal ideas in taming and transforming international competition over time, that you can’t help but see echoes of that in post-Cold War American statecraft.

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned that you were trying to write for something that will still be impactful in 20 years. There are not a lot of incentives in contemporary academia pushing people toward projects like that.

Hal Brands: Well, in history, it’s different. The nice thing about writing history is that in most cases you’re not shooting at a moving target.

We know how World War II ended. You should be able to write something about World War II that stands the test of time if you do it well, and that people can profitably pick up 10, 20, or 30 years down the road. In fact, I’m working on a project that has a chapter about World War II. One of the best books that I’ve read on the subject was published in 1968. That’s definitely possible.

It obviously becomes harder the closer you get to the present. That is an unavoidable dilemma. You can see it, by the way, in all of the volumes in this franchise. We talked about the Hitler essay, an essay on Japanese strategy in the first volume, which cuts off in the middle of the war as just things are getting really interesting. The essay by Condi Rice on soviet strategy in the second volume that leaves you hanging, as you mentioned, five years before the Soviet Union itself comes to an end. There are essays in this volume. We mentioned the essay on Xi Jinping, the essay on the Kim Dynasty in North Korea.

I have no doubt that people are going to be able to read those profitably a number of years from now. Stuff’s going to happen, and they will become dated over time. At some point, somebody will feel it necessary to do a fourth volume of Makers of Modern Strategy. I’m sure that’ll be an interesting one as well.

Jordan Schneider: One of the most surreal essays was “Dilemmas of Dominance: American Strategy from George H.W. Bush to Barack Obama” by Chris Griffin. I lived through most of that history. I don’t want to think that I’m that old, but I vividly remember the start of Bush II’s Iraq war. As someone who’s been reading news obsessively ever since then, it is so surreal to see 20-30 years of history that I personally experienced just slimmed down into just 25 pages.

Unipolarity was, as identified by Krauthammer, a matter of fact. It was the product of the wave of events that left the United States a solitary superpower, bolstered by the resilience of its Cold War-era alliances, an increasingly liberalized world economy, expanding democratization, and the implausibility of any near-term peer competitors. The fact of unipolarity presented Bush and his successors with a fundamental, unexpected question: how should the United States exercise its newfound dominance in the international system?

[The New Makers of Modern Strategy, p. 870]

That seemed to be a particularly difficult one, especially, as you said, how archives are going to be open, and people are going to reevaluate all of the judgments that have been made, particularly over something that’s so recent.

Hal Brands: I will give a special word of thanks to the author of that piece, Chris Griffin, who now basically plays the role in strategic studies that Carnegie played for it in the 1930s and 1940s. His day job is with the Smith Richardson Foundation, which has funded just amazing work on a variety of strategic style-to-use topics over the years. There’s no conflict of interest. They did not fund this project. Chris was chosen entirely on the merits, but they deserve recognition for the work that they have done in this field.

What’s interesting about Chris’ essay is that it helps us understand the degree to which primacy, as much as it was a strategy, was a condition that gave rise to various habits in American foreign policy. Some of those habits were good. Some of those habits were bad. A lot of those habits persisted across multiple American presidential administrations.

The point that Chris makes, which I agree with, is that there was more continuity across post-Cold War American statecraft than we often think, in terms of what international system the United States was trying to bring about, in terms of what it thought threatened that international system and in terms of a shared commitment over a period of at least 25 years to trying to lock in as much of the good stuff, the spread of democracy, the US military advantage over any rivals, the promotion of globalization that followed the end of the Cold War.

We at least have enough perspective on this period. We can look at it over a generation plus to be able to see some of the continuities between administrations and evaluate the period as a whole.

Jordan Schneider: It’s a particularly tricky one to write, because everyone who was in those positions or writing books about every topic at a time is going to have a take that isn’t necessarily the one that they want to be enshrined in Makers of Modern Strategy lore for the next 30 years. Anyways, brave effort by him to try to synthesize all those presidents.

After you get the drafts, to what extent did you try to have them have a coherent tone, and put them in dialogue with one another? What was the back and forth between you and the writers?

Hal Brands: Well, I was downright fanatical on the length of the essays, because pretty early in the process, my editor at Princeton told me that if we got beyond 1,199 pages, and the book is pretty close to that, the spine would quite literally crack, and you wouldn’t have a book anymore. You’d have two separate unbound books at that point. That was one area where I definitely weighed in.

Look, all of the people who contributed to this volume are really distinguished thinkers, writers, and scholars. You don’t want to have a heavy hand in dealing with the stuff they produce. I tried not to mess with the tone of the essays. I certainly tried not to mess with the conclusions of the essays.

There were a couple of cases where I suggested, “Hey, you might consider this dimension of the problem,” simply because I had a degree of familiarity with the thing that people were writing. There are areas where I suggested trims to try to get it down length. There were a few areas where we went back and forth a little bit on not so much directly going into conversation with other essays. The John Gaddis’ essay at the end of the book is really the only one that does that explicitly. Just teasing out key dynamics that I knew were going to be present through chunks of the volume, because I had read all of the pieces in a way that nobody else had.

Again, when you’re dealing with a group of contributors this prominent and this good, the less meddling you do, the better.

Jordan Schneider: There’s a famous story with Robert Caro and Bob Gottlieb in the first edition — or the first book he wrote on Robert Moses, where the first draft was so long that they ran up against the spine problem. In the latest movie, they talk about how cutting down chapters to make it into one volume is one of the biggest regrets of their life.

What’s wrong with doing two volumes? How did you land at the page limit and the amount of topics?

Hal Brands: I’m really a stickler for brevity. I’ve rarely read a 17,000-word essay that wouldn’t have been better as a 14,000-word essay or an 11,000-word essay. I say that as somebody who’s written some 17,000-word essays.

My view was that you could cover most of these subjects with adequate nuance and with adequate depth at 10,000 words, and that readers would get more out of that because they’d be more likely to actually read all of it than they would be if the essays were 20,000 words long.

I love the first volume. I love the second volume. If I have one critique of the second volume in particular, it’s that some of the essays are really, really long and become a little bit difficult for non-expert readers to get through. That was a problem I was determined to avoid. Virtually all of the contributors were on board with that in one way or another. It really turned out not to be a huge issue. I actually think the book is better for it.

Jordan Schneider: Why’d you do this alone? This couldn’t have been the plan from the beginning, was it?

Hal Brands: No, this was not the plan from the beginning. I was initially going to have two co-conspirators in this project. One, is Frank Gavin, my very good friend and colleague at Johns Hopkins, who runs the Henry Kissinger Center there. The other, Eliot Cohen, also of Johns Hopkins, SAIS, was the dean of the school at the time that we were putting those together.

There’s no real story behind why neither of them ended up doing it. They both just ended up with a variety of other commitments that made this hard to do.

Eliot was trying to put the finishing touches on his book about Shakespeare and power.

Frank was putting the finishing touches on two books, one of which was Nuclear Weapons and American Grand Strategy.

Fortunately, Frank was able to contribute to the volume. He wrote a remarkable, idiosyncratic, deeply insightful essay on the perplexities of nuclear strategy, which I think people are going to be getting a lot out of for many years to come.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk a little bit about the Gaddis essay. What was the origin? Why do you think it was so cool?

Hal Brands: John Gaddis was the hardest to get of all of the contributors, despite the fact that he was my dissertation advisor, or maybe because of the fact that he was my dissertation advisor. The calculation was he had already done his part for me and didn’t need to help with this one. In all seriousness, I did finally get him to agree to do it.

What he was really interested in doing was writing a reflection on all of the essays in the volume and explaining them in the context of the larger craft of strategy.

John was an eminently good sport in all of this. As soon as I got the first drafts of the essays, I would read them, mark them up, and send them to John. John would read them and, as we were rushing to get the volume ready, wrote his own essay on this.

His essay covers 2,500 years of history — everybody from Pericles to Putin is in the essay. It does the quintessential John Gaddis thing, where there are four amazing insights per page, and you feel you want to stop and think about the first one, but you’re already on to the second one and the third one and so forth.

It’s maybe 7,000 words. It’s not a particularly long essay, but it’s a really fitting summation of a lot of the insight and wisdom that the other contributors brought to the volume. It’s also a summation of what John has learned and taught us about strategy over a 50-plus-year career studying it. I felt very privileged to get him involved with the project, because I just couldn’t think of anybody better to bring the volume to a conclusion.

Jordan Schneider: Hal, do you have any thoughts or observations of the upcoming generation of scholars, and where their interests are? Where the field is going and what might be different in the 2040 version?

Hal Brands: One thing that might be different is that none of the people in the 2040 version are going to work in history departments. The reason for that is that the discipline of history as it’s practiced in academia has just changed a lot over the past 40 or 50 years.

I would guess that the percentage of contributors to this volume who work in history departments is lower than it was in the 1986 volume, for instance, because the people who study decision making, statecraft, war, and peace — are now as likely to be found in professional military education institutions, political science departments, policy schools, and think tanks as they are likely to be found in traditional history departments.

That trend will continue. I don’t know that it’s necessarily a bad thing. Diplomatic and military history, while they haven’t exactly flourished within history departments in the last 40 years, have flourished in these other spaces.

The makeup of the next generation may be a little bit different. Of course, the issues that they’re preoccupied with and the experiences that they bring to the task will be different as well. If you were writing for the first volume, you were drafting your essay at the end of 1941, you would live through some serious history over the past five years. That shaped almost everyone’s approach to the task.

Same thing. There’s a different set of histories that the people who contributed to this volume lived through. That’d be the same with the next volume as well.

Jordan Schneider: Maybe this gets to the one critique I’d have of the essay collection. One thing that I think really weighed heavily on the 1943 one was the weight of the technological machine age transformation that allowed a world war to happen in the first place.

In the second edition, you had the invention of the nuclear bomb as something that hovered over everything.

My expectation is the 2050 edition will have a number of essays about cyber attacks, AI, quantum computing, or technological changes that aren’t even on our radar yet.

Hal Brands: Haha, the next volume would just be written by different versions of ChatGPT. The revolution will come in a different way.

We do have an essay in this volume, which is one of the more provocative ones by Josh Rovner at American University, which basically says, “None of this stuff is as revolutionary as you think. New technologies come, new technologies go. We always think they’re going to revolutionize warfare and grand strategy. They typically revolutionize it less than we think. Then, the next set of technologies comes on.”

Now, it’s provocative, and people will argue with that thesis. What Josh is doing is exactly in the spirit of the volume, which is trying to historicize the debates that we’re having about cyber and AI and quantum today by looking at how previous technological step-changes have and haven’t changed the practice of strategy.

Jordan Schneider: Do you worry that the field of history, as it aspires to be timeless and everlasting, creates a biased preference for researchers who don’t internalize big technological changes?

Hal Brands: Josh isn’t a historian, he’s a political scientist. We let him in anyway. He did a great job.

Jordan Schneider: Last question — how did you reconcile the goal of decentering the US if Americans were also the target audience of the book?

Hal Brands: I’m not sure that America is the target audience, actually. I try to be transparent about my motives and what excites me about doing this volume, which is to help citizens of the democratic world be better at doing strategy because it matters for our future.

It matters in the present moment, as the democratic hegemony that we became accustomed to after the end of the Cold War is by no means guaranteed. I want the book to help the democracies of the world understand strategy better.

Strategists in Russia or Iran could probably learn something from reading this book. There is something universal about the challenge of strategy, even though every strategic dilemma has its own characteristics.

I would also say that the choice of chapters in the book is deliberate in the sense that it’s meant to get away from the transatlantic focus of the first volume, less so in the second volume. There’s an essay about Tecumseh. There’s an essay about Russian and German strategies under Hitler and Stalin. There are multiple essays about China, essays about Japan, and the Middle East, and strategies of nonviolent resistance India.

You’re right that the US is more at the center of the story than probably any other country. In that respect, the focus of the book is just an artifact of the part of history that it looks at.

Jordan Schneider: Folks, this was not a sponsored episode. I just think this book and this collection is really fantastic. It’s hard for me to imagine a listener to ChinaTalk that’s interested in the sorts of topics that I cover week to week that wouldn’t really enjoy and find this volume valuable. Really encourage you all to check it out and let me know what you think about it.

It might be cool to do some follow-ups if there’s particular audience feedback on a handful of the essays to maybe get a little panel of contributors together.

I do want to close, Hal, with a line that you had in your introductory essay. You say that, “If history is an imperfect teacher, it’s still the best we have. History is the only place we can go to study what virtues have made for good strategies and what vices have produced bad ones. The study of history lets us expand our knowledge beyond what we have personally experienced, thereby making even the most unprecedented problems feel a bit less foreign.

Indeed, the fact that strategy cannot be reduced to mathematical formulas makes such vicarious experience all the more essential. History, then, is the least costly way of sharpening the judgment and fostering the intellectual balance that successful statecraft demands. Above all, studying the past reminds us of the stakes that the fate of the world can hinge on getting strategy right.”

As we enter a scary world in 2025, think everyone would benefit from taking a moment to breathe and read some essays on Jomini, and Clausewitz, and Tecumseh and John Quincy Adams. It’s a good way to spend Sunday mornings.

Thank you so much, Hal. Thanks to all the contributors for putting together such a remarkable edition.

Hal Brands: Thanks, Jordan. It’s great to have this option to talk with you.

It's not like I live in a cave, so I don't know how I missed this book when it first came out. Couldn't click "buy" fast enough! And there's a Kindle version to boot.

Thanks for an outstanding conversation.

Does anyone know if the 1943 or 1980s versions are available as PDFs? Struggling to source a 2nd hand copy here in Belfast. I have paid for a new copy of the new edition of course.