Gary Wang spent the past decade developing business and product strategy for Silicon Valley technology companies, with a focus on enterprise software, the industrial internet of things and AI. He has a degree from HKS and worked in China. The views expressed here represent only his own.

About a decade ago, the best forecasts heralded a promising manufacturing future, in the United States and globally, with the advent of the fourth industrial revolution (also called “industry 4.0,” the “industrial internet,” or “industrial internet of things” aka IIoT). The belief was that the falling cost of cloud computing, sensor costs, and machine learning — coupled with new connectivity technologies such as 5G or IPv6 — would lead to a revolution in manufacturing productivity and ultimately higher GDP growth.

Despite these promising forecasts, multiple data points indicate that US manufacturing has largely stagnated. Analysis from the New York Federal Reserve reveals that both total factor productivity and labor productivity have been flat from 2007 to 2022. Meanwhile, US share of global manufacturing value add fell from nearly 25% in 2000 to an estimated 15% today in 2024. The UN Industrial Development Org projects US share of global manufacturing value add will fall to 11% in 2030, while China may account for 45% of global output.

This decline comes after multiple presidential administrations’ efforts to revitalize American manufacturing — from the Obama-era policies such as the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership or the Manufacturing USA initiative, to the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, and now the Trump administration’s desire to reshore manufacturing via tariffs and other policy tools.

Off-shoring and free-trade agreements go only so far in explaining this decline. And the present debates over US industrial policy — sparked by the advent of emerging technologies (generative AI, quantum computing) as well as intensifying competition with China — perhaps focus on the wrong things.

The real questions US policymakers must grapple with: why did the United States fail to capitalize on technology that was already available to make its manufacturing base more competitive?

Put another way: why have the promises of the IIoT revolution failed to materialize in the United States?

This piece makes a few key arguments:

The “industrial internet of things” is not an industry. It’s a set of disparate technologies that all need to be adopted together to create value.

The free market will not always optimize adopting a broad set of technologies for an entire ecosystem of industries. The underwhelming results of today’s industrial internet is a case in point.

China’s industrial policies to “win” the fourth industrial revolution offer lessons for policymakers in the United States to consider.

When it comes to revitalizing manufacturing, or ensuring American leadership in AI or quantum computing, policymakers need to craft policies to develop entire value chains and tech ecosystems — not myopically focus on just one strategic technology (eg. advanced semiconductors).

What is IIoT?

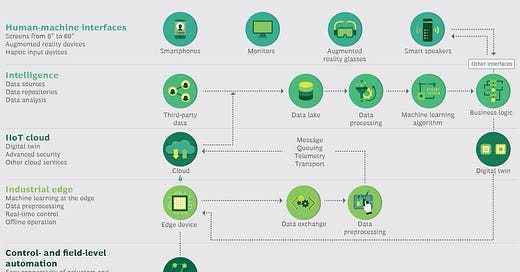

IIoT refers to the interconnection of machines, devices, sensors, and systems which are connected on the internet in performing industrial tasks.

Take one of IIoT’s leading “use cases” (ie. applying tech to solve a business problem): predictive maintenance. Sensors connected to a piece of factory equipment, such as a boiler, can measure temperature or vibration. When combined with machine-learning algorithms, manufacturers stand to save millions by predicting when a machine would fail, and then proactively maintaining the machine before a failure occurs — thus reducing factory downtime and increasing productivity.

Another use case: gathering GPS data from truckers could enable machine-learning algorithms to optimize the routes of commercial trucks (saving fuel costs). When paired with data on customer demand (say, Pepsi sales in a city), manufacturers could save billions by optimizing their inventory costs to ensure that the optimal amount of Pepsi reached store shelves at just the right time.

The use cases are endless: deploying robots on the production line, using cameras and AI to automate quality inspection for finished products, creating a “digital twin” of an entire production process for optimization, and much more. All of these use cases required cloud computing, real-world historical data, and connectivity. As a practitioner who has worked with technology companies on their strategy for delivering industrial IoT to manufacturing companies, I can attest to the level of industry enthusiasm for IIoT during this time (as well as the numerous operational challenges).

How off were the IIoT forecasts?

In 2015, McKinsey forecast $1.2 to 3.7 trillion in economic value created per year by 2025 from IoT technologies in factories. Assuming technology vendors alone capture 5% of the value created — a very conservative benchmark — that’s $60 to $185 billion in revenue. The International Data Corp in 2017 forecast that manufacturers would spend $102 billion in the industrial internet, meaning vendors selling IIoT technologies should see comparable revenue figures. Accenture and World Economic Forum joined the hype, intoning that the “Industrial Internet will transform many industries, including manufacturing, oil and gas, agriculture, mining, transportation and healthcare. Collectively, these account for nearly two-thirds of the world economy.” These market forecasts led the Congressional Research Service in 2015 to predict, “The current global IoT market has been valued at about $2 trillion, with estimates of its predicted value over the next 5 to 10 years varying from $4 trillion to $11 trillion.”

These forecasts were off by multiple orders of magnitude. Today, to my knowledge, there is only one publicly listed company in the United States solely focused on IIoT: Samsara, with $1.4 billion in revenue, growing at a healthy ~40% year over year. (Palantir in 2024 reported $700 million in revenue from US private-sector firms, some of which include manufacturing — but the majority of Palantir’s business is with governments.)

General Electric and Siemens both tried to become technology companies by developing their own cloud platforms and AI applications to digitize the manufacturing sector. A series of New York Times headlines, though, tells the saga of GE’s attempt to capture the purported massive opportunity of the industrial internet of things:

And finally, later in 2018:

Siemens positioned its industrial internet cloud platform, Mindsphere, as its next growth vector. Today, Mindsphere has been rebranded to “IoT insights hub,” and the last time Siemens company leadership talked about Mindsphere on their earnings call with equity analysts was in 2022, indicating a retrenchment in expectations (unlike when they spoke about Mindsphere on earnings calls with analysts in 2015, 2016, 2019, and 2020; what industry leaders tell Wall Street indicates where they think their companies’ growth will come from).

Why were the predictions so wrong?

IIoT is a cluster of disparate technologies that have to work together to create value. It’s not one technology. Consider the aforementioned predictive maintenance use case. To realize value, a factory owner needs to adopt six or seven different technologies from different vendors.

There’s the company providing sensors (sometimes with software) for the machines to gather data for analytics.

Many factories have historically not been connected to the internet, so a company like Verizon needs to get involved to set up an in-plant 5G connectivity network. (Leading analysts have estimated there are only a handful of 5G industrial projects in the United States, compared to likely thousands in China.)

A company like Cisco has to provide the networking equipment to enable internet connectivity in the factory.

A cybersecurity company needs to ensure the sensors and machines, now that they’re connected to the internet, are secure from cyberattacks.

A cloud-computing company, such as Microsoft or Amazon, needs to provide the compute and storage for the customer to develop AI algorithms to analyze the data generated by the sensors. These cloud-computing companies often provide the AI algorithms for customers to customize themselves (assuming they have the in-house data science talent) to analyze the data from factory equipment.

A company needs to integrate these disparate systems together — usually a system integrator like Accenture or Wipro.

The factory owner has a finite budget, must negotiate with six different vendors (each with their own pricing and profit models, none of whom necessarily coordinate their selling activities) — but still must realize a high enough return on investment (ROI) to justify solving this one use case. Imagine a consumer buying a car — but instead of buying from an OEM like Tesla or General Motors, you have to negotiate individually with the tire company, the engine manufacturer, the seat belt maker, the company making the infotainment display, and every other component manufacturer.

The nature of the physical world makes this coordination problem even more complex:

Algorithms aren’t immune from false positives. What happens if the algorithms incorrectly predict a machine will break down, but a maintenance technician has already been dispatched to make repairs? That reduces ROI.

Machine algorithms need to be trained on historical data of when the machine has broken down before — but for many factories, maintenance records aren’t digitized; if available at all, they’re paper logs of when a technician fixed a machine.

Third, from the perspective of the technology vendor, sales cycles to manufacturers often are usually one to two years — since customers will pilot the technology for one set of machines (one use case) in one factory, measure the cost or productivity savings, and then decide whether they want to scale the technologies to multiple use cases across multiple factories. Factory budgets are managed locally, not globally — meaning a vendor has to sell to a manufacturer’s factory site in, say, the United States, then Brazil, then Germany, and so on.

All of these factors help to explain why venture capitalists — with few exceptions — have not invested in startups tackling industrial IoT, as well as why it’s been hard for existing vendors to scale their business. Even McKinsey admitted in 2021, “To date, value capture across settings has generally been on the low end of the ranges of our estimates from 2015, resulting from slower adoption and impact. For example, in factories, we attribute the slower growth to delayed technological adoption because many companies are stuck in the pilot phase.”

What has China done?

While IIoT hasn’t lived up to its potential in the United States and elsewhere in the West, China has leaped ahead in the fourth industrial revolution: there is no other country in the world that can boast of legions of “dark factories” — ie. factories where entire manufacturing processes are automated.

How has China done it? By focusing on technical challenges and market-coordination problems.

First: Chinese policymakers at the highest level — eg. the State Council — crafted policies to solve known technical challenges which threatened to hold back Chinese manufacturer’s adoption of IIoT technologies.

For example, in the predictive maintenance use case, there is a known problem of “asset mapping” — ensuring all the physical and digital assets in a factory can be identified in a common taxonomy to enable machine-learning analytics and then workflow automation (sending a technician to repair a robot, changing the workload of robots working together if one robot is breaking down, etc.). Specifically, if factory owners want to predict when a robot arm will break down, they need a comprehensive way to uniquely identify the specific robot, the specific arm of that robot, the specific sensor that may be attached to the robot, the specific 3D model of the robot’s arm, and then map all of these physical and digital assets together. Without a common taxonomy, it’s impossible to automate the analysis of sensor readings from the robot arm (eg. its grip strength) and then trigger a workflow to fix the robot arm while enabling the production process to continue seamlessly, that is, in a “lights out” fashion.

China’s State Council, in a 2017 planning document — “Guidance for Deepening the Development of the Industrial Internet ‘internet + promoting manufacturing” 深化“互联网+先进制造业” 发展工业互联网的指导意见 — specifically called for implementing networking connectivity and “identity resolution system” 标识解析体系 to solve this problem, using a combination of known technologies and standards such as IPv6, software-defined networking, 5G connectivity, time-sensitive networking, and passive optical networking. The technologies mentioned in this document were available in China (and the United States) in 2017. An identity resolution system (the English equivalent term would be a digital “tracking system”), when combined with advanced networking technologies, solves this predictive-maintenance problem because then a piece of software — such as a predictive-maintenance application for robots — can automatically locate the robot arm that’s emitting sensor data indicating a breakdown, match that to the 3D model that specifies how the robot arm should function, detect issues with the robot arm, and then trigger a workflow to remediate. Dozens of physical and digital systems are involved in solving this problem.

Of course, the free market can solve this problem as well — but it runs into the same issue mentioned above: coordination of multiple vendors with multiple technologies and standards that all have to work together. No wonder that, in 2024, 5G adoption in the US manufacturing sector was at 2%. After all, a factory doesn’t realize any business value from just deploying 5G by itself, if the rest of the technology stack (sensors, algorithms, applications, cloud computing, security, etc.) isn’t also deployed.

Second: China targeted industrial policy to solve known market-coordination problems that would hold back IIoT adoption.

For example, consider the problem of sub-scale platforms. To better understand what this is, I’ll first lay some foundation on key terms:

A platform is any technology in which an underlying resource, such as computing power (eg. Amazon Web Services), is offered to customers as a software component to build a fully functional piece of software. In the IIoT case, “industrial internet of things platforms” are cloud platforms that allow manufacturers to (1) access compute and data storage, (2) enable data to be sent from physical machines to the cloud, and (3) secure the network and data from machine to cloud. An IIoT application is a packaged piece of software with algorithms and an end-user interface that solves a business problem.

The consumer analogy is how the iPhone is a platform and Google Maps is the application that runs on the platform, using its compute and storage. Manufacturers need the IIoT platform, and they must either (1) build the IIoT application themselves (which is difficult since manufacturers often don’t have the in-house talent), or (2) buy a prepackaged application from a vendor.

The sub-scale platform problem occurs when, in a market, there are too many platform vendors who can’t make enough money to scale their business due to intense competition and operational execution issues (identified above) and when there aren’t enough applications to actually create value for the customer, the manufacturer. The IIoT market in the United States has faced precisely this problem, especially because digital-platform markets tend toward winner-take-all or oligopoly competition dynamics (eg. iPhone vs. Android; the four major cloud-computing platforms: Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and now Oracle), and platforms make money only if application vendors build on the platform.

BCG, in a 2017 report titled “Who Will Win the IoT Platform Wars,” identified over 400 IoT platforms in the market due to the excitement of the industry at that time. But few of these platforms really grew to any significant scale, with some notable failures (see GE’s attempt above) because of the technical and operational issues. As a result, there were few IIoT application vendors building prepackaged software. There too many platforms they could choose to build on, and the lack of platforms at scale meant there were too many technical challenges that were unresolved. The value of the platform is to solve the underlying technical issues so an application developer doesn’t have to. In the IT world, a software developer doesn’t have to worry about which type of server or networking equipment is in the data center to build a cloud application. The same is true for a software developer on mobile: they don’t have to worry about the specific type of camera lens on the phone when building their app.

As a result, there are few if any IIoT applications at scale (Samsara being a notable exception). For example, there is no packaged software application that a factory own can buy to predict when any robot it chooses to deploy will breakdown today, or for any other type of equipment (of which there are literally thousands) in a factory.

Meanwhile, China’s State Council, in the same 2017 policy document, designed policies to solve the sub-scale platform problem in IIoT:

By 2020, form the industrial internet platform system, supporting the construction of approximately 10 cross-industry, cross-domain platforms, and establishing a number of enterprise-grade platforms that support companies’ digital, internet-enabled, and AI-enabled transformations. Incubate 300,000 industry-specific, scenario-specific industrial applications, and encourage 300,000 enterprises to use industrial internet platforms for research and development design, production manufacturing, operations management, and other business activities. The foundational and supportive role of industrial internet platforms in industrial transformation and upgrading will begin to emerge.

到2020年,工业互联网平台体系初步形成,支持建设10个左右跨行业、跨领域平台,建成一批支撑企业数字化、网络化、智能化转型的企业级平台。培育30万个面向特定行业、特定场景的工业APP,推动30万家企业应用工业互联网平台开展研发设计、生产制造、运营管理等业务,工业互联网平台对产业转型升级的基础性、支撑性作用初步显现。

Like most industrial policies in China, the State Council’s high-level policy guidance becomes operationalized in provincial- and city-level policies via funding and other incentives. For example, Jiangsu 江苏 province set a goal of establishing 1,000 “smart” (aka enabled by cloud, AI, advanced connectivity, etc.) factory workshops in 50 provincial-level factories by 2020.

What can the United States learn?

If we’re serious about revitalizing US manufacturing or maintaining leadership in emerging technologies such as AI and quantum computing, here are some things US policymakers should consider:

The free market, while efficient for specific markets, may not optimize for transforming entire sets of industries. The technologies for the industrial internet of things were available in the United States — but due to technical and market-coordination challenges, adoption has lagged behind that of China. AI and quantum are foundational technologies that may require an even greater level of market coordination to overcome operational and technical obstacles compared to that of the industrial internet of things.

Industrial policy needs to move beyond tax incentives, tariffs, and subsidies to make calculated bets on specific technologies, with deep technical expertise incorporated early on in the policy process. For example, in AI, the policy debate has focused exclusively on semiconductor subsidies and export controls — but there is limited if any discussion on how to make the AI data center itself easier to build and operate. High energy costs and energy availability due to the limits of the utility grid are known technical and business challenges to data center capacity today. Ultimately, the total cost of using AI to make predictions, optimize processes, and create value (eg. cost of inference) is not just the cost and efficiency of the chips, but the entire data center stack, including energy costs.

Successful commercialization of a set of technologies creates its own positive feedback loop, which reinforces first-mover advantages. Since China has a significant head start in digitizing its manufacturing base via IIoT technologies, Chinese vendors likely have more real-world data (by deploying more sensors), which enables firms to perfect their machine-learning algorithms, which will further improve manufacturing productivity in China relative to the United States. Robot adoption is a key example: when adjusted for labor costs, China uses 12 times more robots than the United States. This deployment of industrial robots at scale further advantages Chinese manufacturers and the entire technology stack associated with robotics (eg. operating systems for robots, robot supply chain, AI software to control the robots, software integrating robots into production processes, etc.). Recent reports of the Chinese government and enterprises mass-adopting DeepSeek only add urgency for more innovative industrial policies in the United States. Therefore, to achieve policy goals such as restoring US manufacturing or maintaining US leadership in quantum or AI, the United States must support companies to actually buy and use these technologies themselves.

While China may have “won” the initial round of the IoT platform wars, it isn’t too late for the United States, with smart policies and leadership, to win the broader industrial-technical leadership competition with China. While some may object to “picking winners and losers,” without urgent policy action, there may only be losers left to pick from.

Can I comment? Apparently yes, so two points:

First, Chinese displays of implementing world-class labor-saving technologies only showcases the absolute irrationality of the Chinese Communist Party: in a country with a vast excess of skilled, low-wage labor, replacing workers with machines is the height of stupidity if the aim is to maximize the general welfare of the country as a whole.

Second, searching for new high-tech ways to boost output per man hour looks pretty silly when you consider there are fairly low-tech ways to achieve the same result, namely, by radically reducing the workweek and tying wages to output. Why do I say that? For two reasons:

First, because workers can work faster for shorter periods of time than for longer, just as in track-and-field the short-distance runners always run faster than the long-distance runners.

And second, because if workers working only part-time are given slightly fewer hours in the week than they might voluntarily prefer, they will be incentivized to exert themselves to the maximum degree possible. I actually tried this in my own small company and got an immediate forty percent increase in output per man hour.

Granted, this whole idea only makes sense if the workers have something to look forward to when they are not on the job. I write about that in a short book for which I am searching for a publisher. Does anyone have any ideas?

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00U0C9HKW

Surely, the fact that the ROIC on manufacturing investment in China is pushed below zero and the state subsidizes the debt service to permit this also plays a huge role here, both in facilitating adoption of technology by Chinese manufacturers and in their foreign competitors' avoidance of major up-front expenditures?