Meituan’s CEO Wang Xing at 40, Without Doubts

I’m Jordan Schneider, the host of SupChina’s ChinaEconTalk podcast. In this newsletter, I translate articles from Chinese media about tech, business, and political economy.

This week on the ChinaEconTalk podcast I chatted with Hal Brands of Bloomberg Views and Zack Cooper of AEI about America’s strategic options with regards to China. They laid out a handful of frameworks for how best to show China that the US means business.

Also, I’m on the hunt for sponsors for the podcast! If you’re interested in reaching an engaged audience of over 3000 China-watchers, just respond to this email.

Meituan’s Wang Xing at 40, without doubts

He Jiayan 何加盐, The House of Startups (创业家) May 25, 2019

美团王兴,四十不惑 (a Confucius reference)

“From a pile of dead men, he pushed himself forward,” said an anonymous investor.

Serial entrepreneur Wang Xing had over a dozen failed projects under his belt before striking it rich by founding Meituan, one of China’s most successful mega-apps. In a longform profile, author He Jiayan details Wang Xing’s failures in first imitating Twitter, then Facebook, and then finally finding success adapting the Groupon model to China. He is also known for picking fights with half of China’s internet companies. It remains to be seen just how far his ambition can take him. What follows is an extended paraphrase of the piece.

Wang Xing’s family suffered greatly after the PRC took power. His grandfather was driven to suicide during the Cultural Revolution, and his father spent years forced to work in the countryside and unable to attend college on account of his family background. After China’s reform and opening-up, however, his dad made a fortune in construction.

Admitted to China’s prestigious Tsinghua University in 1997, Wang left an impression. For instance, during hot pot with classmates one night, the upperclassmen gave all the freshmen an opportunity to ask a question all the seniors would have to answer. They expected Wang to ask about secret crushes, but instead he said, “What do you think is the meaning of life?”

Wang Xing headed to the University of Delaware for his PhD, but got bored when his advisor went on sabbatical. He later said that had he been in a top PhD program he wouldn’t have had the chutzpah to quit. After returning to China and fumbling around with clones of Google Maps and Evite, he stumbled on success with a pixel-for-pixel Facebook copy. But he suffered from a lack of investment—having lost his one-page business plan on the way to his meeting with Sequoia China, he tried to hand-write a proposal on the cab ride over—and was eventually forced to sell to a competitor for a paltry $2 million.

Wang Xing’s next idea was yet another “Copy to China” endeavor. In April 2008, he launched a Twitter clone and quickly amassed over a million users. But out of the blue, the government blocked his site for nearly two years.

Writes the author, “The concrete reason for the ban is hard to pinpoint. But the root cause lies in the fact that during the site’s development, Wang Xing failed to realize that at a certain size, it takes on the attributes of media. Improper handling of certain information caused the site’s doom.”

Most of the employees from that time stuck around through the dark days of censorship purgatory. One of the few who did not was Zhang Yiming, who would go on to found Bytedance.

For his next move, Wang Xing drew yet again from American startups for inspiration. His Meituan was one of about five thousand Groupon clones that launched around 2011. So how did Wang pull ahead of the pack?

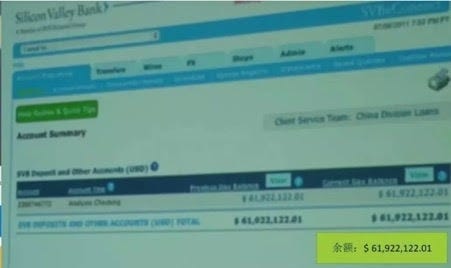

For starters, he decided to only launch one product a day, ensuring that the merchants really felt the benefits of his partnership. Also, Meituan was the first to guarantee automatic refunds for customers whose purchases expired. While his competitors were burning cash to gain market share, Wang preserved funds, reckoning that other firms’ ad spend at the time would help educate the customer but not necessarily breed loyalty. Through his frugal management he won the trust of major investors and was able to raise a huge round. Next he went on social media to brag about it, and in doing so scared off competitors and won the trust of customers who worried about their purchases being wasted.

The bank account flex

Starting in 2013, Meituan took on Baidu and Ele.me (now aligned with Alibaba) on food delivery, investing a cool billion RMB in an operation to “storm a beachhead.” Meituan has since grown to control over 60% of the market.

Since 2015, after Meituan’s merger with Dazhong Dianping (closest Western analogy: Yelp), Meituan has been engaged in “borderless competition.” It has picked fights with Ctrip on travel, adopting the Maoist strategy of “encircling the cities from the rural areas” by starting in lower-tier cities. By last year, Meituan had started to book more hotel rooms per night than the former industry leader.

Wang Xing met future Didi CEO Cheng Wei back in 2011, just as he was getting his firm up and running. Wang even gave him some tips on his app. For years, they maintained a friendship. In 2017, they had dinner together; later that night, Wang Xing launched his own ride-hailing service pilot in Nanjing. “That night, Cheng Wei certainly understood how Xi Jinping felt when during the day he was laughing with Trump at his private estate, but at night Trump was mulling over sanctions.” As Didi invested in bike ride-sharing startups Ofo and Bluegogo, Meituan bought out rival Mobike. Just this month, Meituan has launched an API to bring all of Didi’s smaller competitors onto one platform.

The author summarizes:

Wang Xing’s path as a founder is at once filled with thorns and flowers. His strengths are inseparable from his weaknesses. He has low EQ, he often offends, and he doesn’t have any partner to make up for this deficiency.

When he made a social network, the product was solid, but he couldn’t find an investor and was forced to sell.

Because he accepted Tencent’s investment, he and Jack Ma had a falling out. In contrast, Cheng Wei was able to make it work and have both Tencent and Alibaba on his board of directors.

In public, Wang Xing has called out Jack Ma at least three times. First he said that Alibaba would stoop to any low, that Jack was a liar, and that Taobao started out by selling fake and shoddy products.

He despises people who don’t do the hard work of thinking through strategy. He once said, ‘Most people are willing to do anything in order to avoid having to really think.’

According to the author, Meituan has three main weaknesses. First, having made so many enemies, Wang Xing may grow distracted from his core customers and get consumed with border fights. Second, Meituan has yet to really bring innovation to the market. Finally, although out-executing others has served Meituan well so far, it remains to be seen how this limitation will fare during a period of dramatic technological change.

I didn’t translate a big chunk of this piece which talks about Wang Xing’s internet theorizing because I found it a bit much. At the core of Wang Xing’s success isn’t some grand vision of the online ecosystem but rather the willingness to run with lots of models proven successful in the West and the skill to execute them at a higher level than his Chinese competitors. Once Meituan was on solid footing, his ‘investing in vertical after vertical and see what sticks’ only underlines the point.

However, I find the desire to be seen not just as a successful businessman but a theoretician an interesting continuity between the Chinese internet world and communist party history. As illustrated in Stephen Kotkin’s epic Stalin biography, to get taken seriously, young Koba felt the need to make a theoretical contribution. In Julia Lovell’s brilliant Maoism: A Global History (which is getting a two-part treatment on ChinaEconTalk soon), Mao had a singular focus on making sure the whole world was waging revolution under his dogmatic paradigm. Even today, for Xi Jinping it wasn’t enough to consolidate power and get a term extension, he also wanted his doctrines enshrined in the constitution to signal that he had truly arrived. The parallel in the West is CEOs aspiring to ‘thought leader’ status but the level of abstraction and method of thinking seen in Chinese tech, perhaps unsurprisingly, betrays slight traces of those mandatory university Marxism classes.

Wang Xing’s ‘Three Vertical and Four Horizontal’ theory. The answer was that the web 2.0 social version of Alibaba was Groupon/Meituan