They called him “Sleepy Joe.” They said he couldn’t get anything done. And then, in the last week of the administration, Biden made us do two emergency podcasts in one week!

To discuss yesterday’s export controls, ChinaTalk interviewed Greg Allen from CSIS.

We get into…

New foundry requirements that attempt to shut down the TSMC-to-Huawei pipeline,

How Commerce’s redefinition of “DRAM” closes a major loophole outlined in our last podcast with Greg,

Whether this rule will bankrupt chip design startups,

Whether Biden-era regulations will have staying power across administrations,

The qualifications of Jeffrey I. Kessler, Trump’s pick for head of BIS,

What this week’s export control package says about the IC’s timeline for AGI.

Shell Companies, Shattered

Jordan Schneider: Greg, how are you holding up with this export control bonanza?

Greg Allen: I am running on fumes, but if the public thought we were too tired to record a podcast, they were sorely mistaken.

Jordan Schneider: What came down the pipe today, Mr. Allen?

Greg Allen: This new rule was really the missing piece in the big update that just came out. For the uninitiated, the AI diffusion rule came out on Monday and is designed to try and stop large-scale AI chip smuggling to China. But there was another problem that got less coverage — it turns out that Huawei, which has amazing chip design capabilities but doesn’t have access to amazing chip manufacturing capabilities inside China, was still doing okay because they had access to amazing chip manufacturing capabilities in Taiwan. Namely TSMC — the exact same company that makes chips for Nvidia. As it turns out, TSMC was making massive, massive numbers of AI chips for Huawei, in violation of US export control rules.

The Bureau of Industry and Security had already sent an “is informed” letter to TSMC which essentially told them to shut all of that down immediately. This rule is the follow-up to that “is informed” letter. Everybody’s been expecting this, but the solution they landed on is pretty remarkable. Things are kind of never going to be the same for TSMC, at least not at the FinFET node or better. For companies that are already established customers of TSMC — known, legitimate designers of AI chips — it’s not a big deal. But the Huawei’s strategy of creating another shell company to buy hundreds or thousands or millions of AI chips fabbed in Taiwan for use in China is over. For China, that’s all going to be shut down. That’s one big piece of this rule.

The second big piece of this rule was designed to address some limitations that Jordan, Dylan Patel, and I talked about in the podcast on the December 2 rule, which restricted DRAM and high bandwidth memory manufacturing in China. Now, they have changed the definition of DRAM. A lot of regulations that previously didn’t apply to facilities at companies like CXMT, now apply.

Those are the two big muscle movements of this rule. Even if you thought there wasn’t more they could possibly do, this was legitimate unfinished business. They absolutely needed to do this as soon as possible.

Jordan Schneider: During our last podcast together, Greg, we gave the December 2nd rule a C+/B- grade. With the addition of Monday’s diffusion rule and this foundry rule, how would you grade the entire export control package?

Greg Allen: The focus of that rule was largely on DRAM and HBM. We had complained that CXMT would still be able to buy large categories of equipment, even if they couldn’t buy everything. That was one of the big failure modes of the rule, which was part of the reason we gave it a C-.

Apparently, somebody in the government listened to that podcast, because we’ve now received a new definition of DRAM. This is very esoteric but if folks can bear with me for a second, it will make sense.

The original October 2022 rules set the standard for DRAM manufacturing that was prohibited on an end-use basis at 18-nanometer half pitch. This means if you’re a DRAM manufacturer in China and you approach an American equipment company saying, “Please sell me your high-end equipment to make 16-nanometer DRAM,” the answer would be no. However, if you say you’re only going to make 20-nanometer DRAM, the answer would be yes.

The issue here is that the US government had a decent definition in October 2022 with this 18-nanometer half pitch, but in October 2023 they issued a rule clarification related to some bit density calculation from IRDS. This is esoteric, but here’s the punchline — nobody in the semiconductor industry uses the IRDS definition except CXMT. This allowed CXMT to claim they were making 19-nanometer chips, permitting them to purchase fancy equipment. Under a microscope, these chips look like Samsung’s 16-nanometer chips.

All these purchases, which violated the intent of the rule and had been prohibited until this rule definition update in October 2023, were allowed to proceed. Now they have revised the definition to align with industry standards — what everyone else in the world uses as the definition, except for CXMT and other Chinese companies seeking convenient loopholes. This loophole closure is great, though it should have happened about a year and a half earlier.

This represents a significant change. All CXMT facilities connected by wafer bridges to their advanced chip node manufacturing facilities, all claiming to make “20-nanometer chips,” will now be cut off from American equipment. According to news reports, an update to Dutch and Japanese export controls may be coming soon. Hopefully, this will include additional categories of technology restricted on a countrywide basis to China, specifically those useful for making HBM. Blocking China’s access to high-bandwidth memory manufacturing is crucial for winning the AI race.

Jordan Schneider: At this point, I feel like they’ve earned a B+ grade.

Greg Allen: Absolutely. This is indeed a huge improvement over December 2, particularly regarding the memory aspect.

To refresh everyone’s memory on why this matters, when you open any AI chip like an NVIDIA H100, you’ll find the big AI accelerator at the center — that’s the part NVIDIA designs. It’s surrounded by high-bandwidth memory chips. Creating AI chips requires both the AI accelerator, manufactured by a logic chip manufacturer, and the HBM, produced by a memory chip manufacturer.

Huawei acquired many AI accelerator logic chips while TSMC was manufacturing for them. The hope is they are now bottlenecked by access to HBM. Cutting them off from HBM sales from companies like Micron, SK Hynix, and Samsung is crucial. Additionally, blocking Chinese companies like CXMT and HMC from domestic HBM production completes the strategy. This rule effectively addresses a pressing national security need and significantly improves upon the December 2 rule.

Jordan Schneider: Can you explain the foundry restrictions?

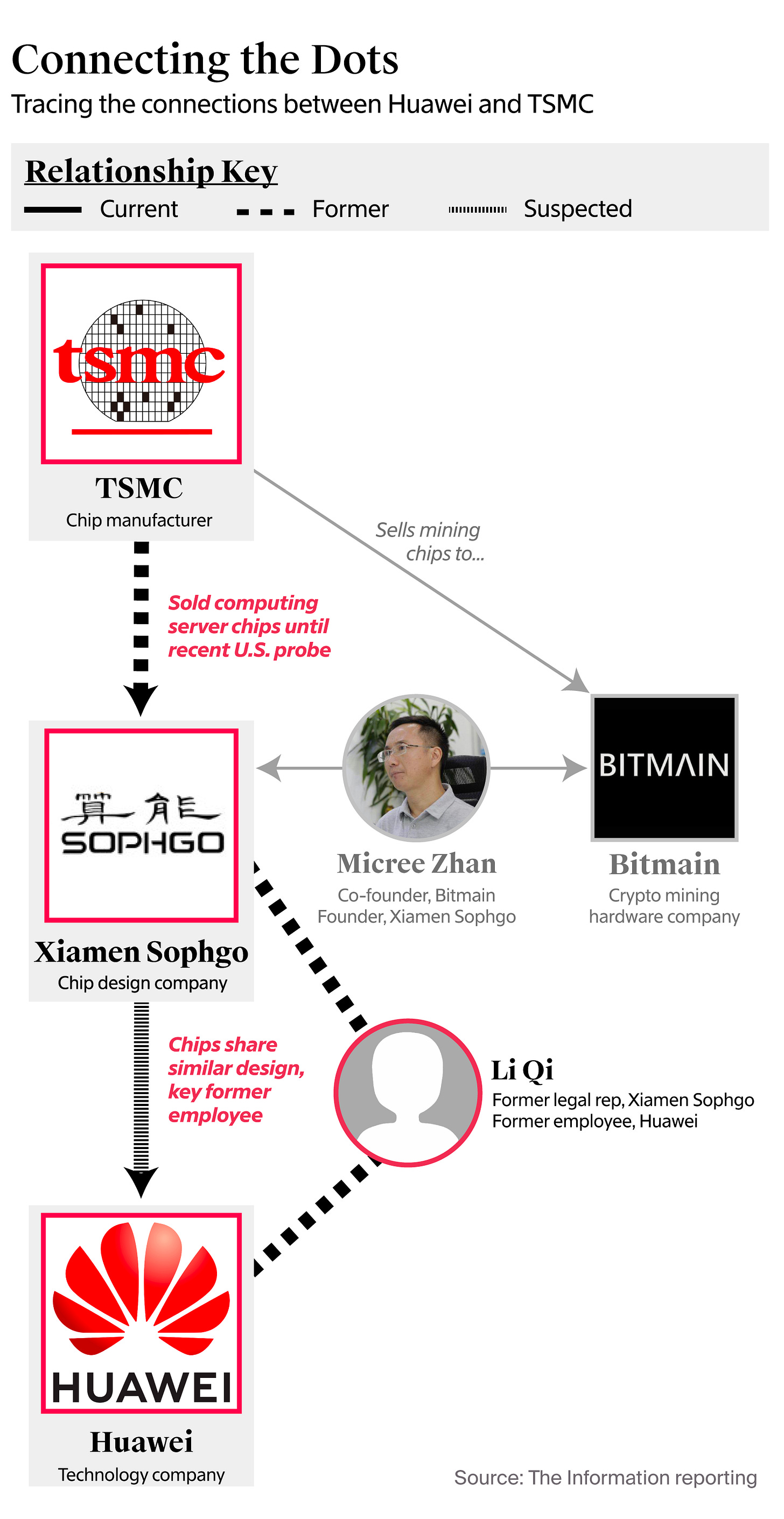

Greg Allen: The problem they’re trying to solve involves Huawei, wearing a metaphorical wig, mustache, and hat, pretending to be another company called Sophgo, which managed to buy hundreds of thousands of millions of chips.

The original solution proposed in the October 2022 rules included not just the regulations themselves but also “red flag guidance.” Chip companies’ compliance lawyers, upon seeing certain “red flag” indicators, should automatically assume something suspicious is occurring and subject that activity to additional due diligence and scrutiny. For example, when receiving a GDSII file (the software package sent to TSMC with chip design specifications) for FinFET transistors, certain elements would trigger red flags requiring further investigation.

TSMC wasn’t particularly effective at implementing this red flag guidance, which allowed Sophgo to succeed by masquerading as a non-Huawei entity. Addressing the shell company problem — not just in this specific instance but in all potential variations — requires extreme measures.

These AI chips are classified under the ECCN number 3A090. For anyone wanting to make non-planar chips at 16 to 14 nanometers or below at a fab, strict restrictions now apply. Regulators were facing two problems here.

First, there is the technical problem of identifying super-advanced AI chips without burdening manufacturers with compliance requirements for less strategic components like jet ski fuel intake pump controllers.

The ideal solution would allow TSMC to calculate a chip’s processing power (measured in FLOPS) from the GDSII file alone. However, this remains technically impossible until the chip is manufactured and integrated with HBM for testing. The red flags were designed to give TSMC a workable technical evaluation.

The red flag guidance has been revised significantly. Rather than 50 billion transistors on the die, the new threshold is 30 billion transistors. This limit will increase gradually to align with overall chip performance improvements. The 30 billion transistor standard means more chips will fall under scrutiny. While calculating FLOPS remains impossible at the design stage, counting transistors is feasible. TSMC must now generate a technically derived estimate of transistor count.

Previously, Sophgo would simply declare their designs had fewer than 50 billion transistors, and TSMC would accept this claim without verification. The new technical requirements prevent this practice.

The second aspect of the regulations addresses methods for identifying shell companies themselves.

Jordan Schneider: Can you explain the white list and the black list?

Greg Allen: Beyond the technical question of identifying chips of concern, regulators must determine which customers require scrutiny. Their solution involves creating an inverse of the entity list. While the entity list identifies prohibited buyers, this rule establishes an “approved designer list” — effectively a white list. Companies are already included on this list at the rule’s launch, including NVIDIA, AMD, and non-American companies like Sony and Mitsubishi. These companies’ experience buying from TSMC or any global foundry will remain largely unchanged, with no new restrictions affecting their purchasing rates.

The challenge arises with startups that declare they aren’t Huawei in disguise. Without proof, TSMC needs a process to obtain permission to sell to them. These companies must undergo the process of being added to the authorized designer list, involving extensive notification and due diligence requirements — considerably more than previously required. It’s somewhat draconian, but TSMC must face consequences after producing numerous AI chips for Huawei.

This creates a potential issue for U.S. chip design startups seeking TSMC access, as the authorized designer list process takes multiple months. Speaking with policy designers, there are plans to expedite this process, particularly for American companies. The authorized designer list is designed to transition in a year to more of an express lane model once they’ve added desired companies and established proper due diligence processes. These measures are extraordinary but necessary to prevent Huawei from accessing TSMC again.

Jordan Schneider: It’s worth noting that companies making chips this advanced aren’t small startups. They require R&D expenditures in the eight figures just to begin manufacturing on the advanced node for major players. And also, this protects them from being blown out of the water by Huawei…

Greg Allen: The distinction between startups making coffee maker chips versus those making NVIDIA-class chips is significant. These ventures are extremely expensive — NVIDIA invests heavily in its design teams for such development. While we use the term “startup,” we’re referring to extremely well-capitalized companies.

Jordan Schneider: The high-six-to-low-seven-figure one-time compliance cost for getting on the list is substantial but won’t necessarily determine a company’s viability.

Greg Allen: The main challenge with this rule isn’t the financial cost of due diligence but rather the weeks and months required for processing. This timing concern explains why they pre-populated the white list with major global designers and designed the rule to evolve into an express lane system after a year of maturation.

Enforcement is a Thankless Job

Jordan Schneider: BIS now has a lot more work than they did three days ago. Do you think they can pull all this off?

Greg Allen: The U.S. government faces a terrible trap. Congress dislikes hearing about BIS allowing xyz companies to sell to Huawei, since Huawei is on the entity list — this was very controversial in American politics in 2020, 2021, and beyond. Congress expressed anger at BIS for not achieving desired export control outcomes, responding by refusing to raise BIS’s budget, or even cutting it in some cases.

As a father now, this would be like if I told my child, “I’m so disappointed in how weak you are, so you won’t get dinner tonight — I’ll starve you until you get stronger.” But you need food to get stronger, just as you need money to accomplish difficult tasks in large government bureaucracies. We’re stuck in this death spiral where we keep demanding more from BIS while withholding necessary resources.

Think about what’s happened to the budgets of Russian smugglers since Russia invaded Ukraine, or Chinese smugglers’ budgets since the October 7, 2022 rules. Their budgets have increased exponentially, while BIS’s budget remains flat or declining in inflation-adjusted terms.

Undersecretary of Commerce Alan Estevez spoke at CSIS yesterday, noting that before the first Trump administration, BIS rules were typically 30 pages — now they’re routinely 260 pages. They released one Monday, another Tuesday, this one today, with possibly another later this week, though thankfully not AI-related.

The expectations placed on this agency — several hundred humans overseeing trillions of dollars of global economic activity — are unreasonable.

For the price of one helicopter, a properly-funded BIS could generate returns for national security unmatched anywhere in government.

Congress may be upset with BIS leadership, but new leaders are coming. They need resources to execute this strategy — anyone refusing to provide that support shouldn’t claim to be tough on China.

Jordan Schneider: These recent rules demonstrate the organization’s increasing sophistication and government learning. Compared to our October 2022 discussions, the mistakes are becoming less frequent. They’re learning to play to their strengths rather than attempting strategies beyond their budget capabilities. Moving toward countrywide controls, requiring TSMC to handle verification, and implementing the diffusion rule by placing checkpoints strategically for easier enforcement — these demonstrate BIS’s technical expertise and realistic assessment of their capabilities.

Greg Allen: That’s very well articulated. However, none of that replaces the need for more funding or an upgraded IT system to replace their 20-year-old infrastructure. These professionals need proper resources, and I sincerely hope they receive them.

Jordan Schneider: None of this substitutes for simply appearing on ChinaTalk when the rules are released, sparing us from guessing their meaning. The practice of holding webinars two weeks after rule releases is ridiculous.

Greg Allen: Agreed, absolutely. If I could add one point — if I were Donald Trump or Mike Waltz, the incoming National Security Advisor, one of my first week’s priorities would involve gathering the Secretary of Commerce, the Undersecretary of the Bureau of Industry and Security, the CIA director, the NSA director, and the ODNI head around a table for introductions. I’d then address the CIA and NSA directors specifically, asking them to outline their plans for supporting their colleagues’ success.

Jordan Schneider: Jeffrey Kessler is being floated to lead BIS — looking at the spectrum of Trump appointees, we had Pete Hegseth for Secretary of Defense on one end. Then there’s Jeffrey Kessler, magna cum laude in philosophy and classics, learned some Chinese, prior Commerce experience, spent the past 15 years practicing China-related law. I’ve reviewed his speeches — he’s a serious professional. This is manna from heaven! It could have been so much worse!

Kessler on Trump’s trade policy, 2019. Source.

Greg Allen: Here’s someone who examines the CIA’s Cold War toolbox with genuine interest. That doesn’t mean the extreme scenarios like orchestrating a coup in Venezuela — the Cold War playbook worth revisiting here is the use of intelligence to enforce export controls. I’ve studied declassified CIA reports from the 1970s and ‘80s about preventing Soviet access to semiconductor manufacturing equipment. Their work was impressive. The intelligence community succeeded then — they should return to these roots. Export controls matter, and the IC can contribute to their success.

Jordan Schneider: One thing worth reflecting on is how “America First” the diffusion rule appears to be. It literally puts America first in line for GPUs, and the rest of the world is supposed to adapt. I wonder if this rule shifted after the election results to make it more appealing for a Trump administration to continue.

Greg Allen: As part of the outgoing Biden administration’s plan to deprive us of sleep, the diffusion rule was part of a one-two punch. Monday’s diffusion rule admittedly makes building big data centers outside America more challenging. Tuesday brought the new executive order on AI energy infrastructure, focused on streamlining construction in America. These rules align perfectly with Donald Trump’s campaign messaging about AI’s future, infrastructure, and energy.

I believe there’s about a 0% chance those rules will survive unmodified. But when Trump’s team comes in to tweak what they want to tweak, I think they’ll find a lot that they like about these regulations.

A hearty farewell to the Biden export control team

Jordan Schneider: The Biden team deserves credit for their forward-thinking approach over the past few years. Implementing the October 2022 controls before ChatGPT’s release — though imperfect, showed that Washington’s national security officials grasped AI’s importance before the stock market. The diffusion regulations particularly demonstrate foresight, essentially preparing for the world of 2026 and 2027.

Greg Allen: My interpretation of the diffusion rule makes more sense in the context of o3 and the ARC-AGI benchmark. Consider that Dario Amodei, Sam Altman, and Demis Hassabis all believe AGI is potentially just years away, with significant national security implications depending on whether the United States or China achieves it first. The diffusion rule looks like an emergency measure for when AGI appears imminent and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

While their strategic foresight impresses me, I’d offer a different compliment relevant to the Trump administration, one I hear from industry. Regarding the energy rule, the Biden administration not only crafted an excellent strategy — pleasing to hyperscalers reading the energy executive order — but also mastered the intricate details of implementing these interlocking mechanisms effectively and legally.

This contrasts with the first Trump administration’s first year, when many initiatives were overturned by courts until Lighthizer arrived. Lighthizer’s strength lies not just in vision but in legal implementation expertise. Beyond good strategy, which everyone recommends, my advice to the incoming Trump team is that details are critically important when executing AI policy moves.

Jordan Schneider: We’ll see. I want to limit myself to one emergency pod per month for my own personal sanity. But the over/under on the first three months of the Trump administration is probably something like six emergency podcasts.

Greg Allen: You’re going to break your own record, if I had to guess.

Jordan Schneider: I can’t take it. Greg, we gotta stop. We need an interregnum.

Greg Allen: We have children to raise! People, please have some mercy.

Hope you feel better, Jordan! You sounded a bit under the weather on this one.

Also hope for your health that there isn't a set of emergency podcasts covering the new administration dismantling pieces of what you covered here...

Regarding the disparaging comments on Sophgo. Sophgo posted this statement in October 2024 https://www.sophgo.com/post/414.html. I'm amazed at the short term thinking that imagines that 'kneecapping' and sanctioning of competitors or 'adversaries' is a 'win'. In the long run the 'adversary' will simply buy non-US or create their own alternatives. As a British company we've also been affected by US 'design/make in US' rules - what happened to the 'special relationship'? - which leads me and others to view USA as an unreliable trading partner.