New Export Controls! SemiAnalysis, Fabricated Knowledge, and Asianometry with Only the Hottest Takes

“China domestic chips — that’s the only viable solution they have.”

BIS just released revisions to the restrictions of October 7, 2022. Jon of Asianometry, Dylan Patel of SemiAnalysis, and Doug O’Laughlin of Fabricated Knowledge join the pod to discuss what these regulations mean for the future of China’s semiconductor and AI ambitions.

Jordan Schneider: A preface to this conversation: recording this soon is irresponsible! Our takes are very much half-baked and subject to change. Today we’ll be working through, what we think are the implications of the regulations.

To recap, the October 7 edifice had two parts:

Restrictions on exports of high-performance finished chips, which can be used to train things like frontier AI models.

Restrictions around semiconductor manufacturing equipment needed to make fancy chips.

So let’s walk through in sequence and start with the thing we probably have the highest degree of confidence of what the implications are: the AI chip restriction side. What were the AI chip restrictions? What were its flaws? And how have they changed with these new regulations?

Dylan Patel: The prior regulations accounted for performance of the chip and for chip-to-chip interconnects, the most important metrics in AI chips. Although, the way they designed the regulations made it so that you could just turn down one lever of a chip — and still have it be amazing at everything else — so the chip can still be shipped to China.

Nvidia did just that: they released the A800 and H800. Intel made a version of their Gaudi chip that passed regulations, and other folks did that, too. So the chips could bypass regulation and make their way to China — that was a pretty big flaw. There was a quarter where Nvidia stopped shipping chips to China, but then immediately after resumed.

The new regulation really rectifies this. It is near perfect in terms of being able to close every gap with respect to this.

It not only accounts for performance, but also does some things around chip density. So if you’re making chips and just shipping the chiplets to China for final assembly — the regulations also protecting against that.

Doug O’Laughlin: The density performance move essentially even gets around some of the fan-out stuff like a lower chip with higher interconnect.

Overall, a smart move — but also pretty draconian.

Almost the entire line of Nvidia’s chips is completely banned in China, with the exception of maybe the 30A series. But for the most part, the measures are pretty draconian — there’s no way they can meaningfully get around the restrictions.

Jordan Schneider: We have this gray zone where, with the H800, Nvidia basically tiptoed right up to the line of where BIS sat. And now you have this new regulation where, if you’re going to export chips that are just under, you have to notify BIS, and they have twenty-five days to give you the thumbs up or thumbs down. So the tiptoeing is going to have to go through at least one other hoop.

Initially, it was trying to allow the Nvidia and AMD chips — ones you use to put in a PC to run Assassin’s Creed or similar games — to not be applied to this. I’m curious, Dylan and Doug, to what extent do you think someone can or will try to run a truck through that cargo?

Dylan Patel: This one is very hard to run a truck through. They’ve set the bar impressively high.

It will be very difficult for anyone to make “the China version” of a chip and ship it there.

What won’t be hard to do is to buy chips from somewhere else — contraband. Chips are pretty small. But then they wouldn’t be able to buy tons and tons of them or billions of dollars worth every quarter. But I’m sure they’ll be able to get some into China. However, I don’t think the whole “being able to make a version for China” is really possible or, frankly, anywhere near the same performance as the chip that we have everywhere else.

Jordan Schneider: So there’s no technological pathway you envision that Intel, AMD, and Nvidia could try to go down?

Doug O’Laughlin: I’m sure they will figure out something clever — but the memory bandwidth restriction is really the killer. It just seems as though there’s no way to get around it in any satisfying manner. Maybe you could get around it, but the chip you get would be very mediocre. They’ve done a really good job of closing the loophole.

The previous loophole essentially moved it all the way down to the lowest level, and China’s response was to fan out. “Yes, this way will be slower,” they thought, “but we’ll just buy as many as we can.” Fanning out of the networking side is going to be a lot harder now.

Honestly, the solution is domestic chips — that’s the only viable solution China has.

Jordan Schneider: Still on the AI chip exports: Dylan already mentioned this idea — you can just buy them and sell them somewhere else. We’ve seen Russia be very successful at figuring out how to do just that when it comes to manufacturing — for example, using tooling equipment to make tanks, artillery weapons, and whatnot.

As for the forty countries — we have had some debate over the past few hours on our group chat as to which ones they apply to, but there are a whole lot more than forty countries on the planet. I wouldn’t even trust those forty countries to be really great when it comes to overseeing all this.

There are going to be games that will surely be played when it comes to what’s going to happen with the re-export — but sales in the high hundreds of millions, billions of data-center chips into China (which will be relevant if you’re trying to build out and train or deploy GPT-6) don’t necessarily seem to be in the cards.

When it comes to the chips that are going to be necessary for training versus inference — to what extent are they different? And how did these restrictions impact one versus the other side of that equation?

Dylan Patel: There’s this misnomer that you can use worse chips for inference, but that’s not really the case. For example, GPT-4 inference is done on H100s, the most advanced chip in the world. It’s not just done on one chip — it’s done on something like ninety-six at a time. That’s what is required just to run the model. Of course, training it requires tens of thousands of chips. We’re going to get models that are 100,000+ chips very soon, probably next year. The leading-edge chips are also what’s required for inference. So to deploy these models is just as difficult as training them.

In fact, more GPUs are required to deploy the model because of how many people are going to use it — whereas to train the model, you can bulldoze your way through. With Microsoft Copilot, it’s going to take hundreds of thousands of GPUs — whereas GPT-4 was trained on only 20,000 GPUs. So there’s a stark contrast between model training and what it takes to actually deploy it to people; maybe it was even a ten-times difference.

Jordan Schneider: So the rule is tough — we saw a problem and we addressed it. The frustration I have: this is something they should have realized ten months ago. A weird move by BIS was not saying to Nvidia, “Hey, we’re going to do something about this, so you guys should not spend all this engineering time to sell chips into China.”

Semicap Equipment Restrictions

Jordan Schneider: On to the real beast: equipment restrictions. So we have a lot of new things that weren’t controlled but now are; and we have tweaks to the things that were previously controlled. What struck a chord regarding the specific equipment restrictions?

Doug O’Laughlin: A lot of the tools get copied, too. If you send an Applied Materials tool into China, I promise you that some of them will go into a lab that is completely focused on how to break it all into thousands of subcomponents and mimic that performance.

Dylan Patel: Who was it that we saw at SEMICON? They just had an Applied Materials Endura — it looked exactly the same, but it wasn’t the same tool.

Doug O’Laughlin: It was Naura.

This is historically how China has gone up the curve: they copy a good product, they make it cheaper, and then they try to improve it themselves. But I just think that preferentially doing that to semicap and not to EDA doesn’t make any sense to me at all. In the long-term, they’re going to end up with the same outcome.

Dylan Patel: You could argue that US competitiveness is going to be much better with software than it is with physical manufacturing just because of what people study and research, and what people are pushed to in society. Obviously America has the leading market share in deposition etch, metrology, and inspection.

They’re going to continue to expand their seven-nanometer production. The China analysts that I have spoken to think that the fab was at 20,000 wafers a month capacity. And if you use any of the yield estimates that the US government believes in, you can get to that number very easily as well — actually, you can get higher than that. So you’re restricting very tightly in some places, but you’re saying now, “Go build this.” It just seems like a very flawed way of thinking.

At the same time, there are significant harmonizations to what Japan has done on the deposition and edge side of things.

Doug O’Laughlin: One of the benefits and true competitive advantages of EDA tools: they’re cobbled together with thousands of different EDA libraries which have all come into this conglomerated, difficult-to-replicate whole. A design team with a lot of effort could probably replicate one, two, three, five of these things — but it’s very hard to replicate a thousand all at once.

So I think that the EDA tool is one of these things where capitalism can’t do it. You give a startup $250 million and ask it to recreate the EDA tools — it could never. But if you give a nation-state that money — that’s more realistic. Only if they have massive financing and tons of time can they crack each individual EDA module over time, especially if it’s pirated. So the EDA tool restrictions have never made any sense to me.

Jordan Schneider: We're going to skip the tweaking of US persons because it seems heavy on the legal side and confusing. There are still some other bits that I think we can say moderately intelligent things on.

Coming back to the advanced computing chips rule where they had this circumvention protection — I really liked the licensing requirement for any company whose parent company is headquartered in Beijing because of the obvious loophole where Alibaba, as long as it was the Singapore subsidiary (or the American subsidiary for that matter) could just buy chips. Now that that isn’t a thing; they’ll have to wait for SMIC to come out with their AI accelerator.

Two things that we’ve talked about in previous editions which we think are moderately impactful but have not been addressed in this round of the rule is:

The servicing of foreign tools currently in China which may be being repurposed for chip manufacturing — which ostensibly the US government does not want;

Chinese firms’ access to cloud-computing resources coming out of AWS, Google Cloud, and such.

If you’re Tencent (or even the PLA, I think!) and you want to train and deploy a model using AWS, there’s nothing stopping you from doing that in these new restrictions. It’s just that you can’t buy and run the chips yourself.

Dylan Patel: I think that they don’t want any US content for equipment that reaches certain levels. The question is, “How far can ASML try and argue that their equipment isn’t US content?” Because they’ve bought many American companies over the years, and a lot of the engineering happens in Boston, in San Diego, and all the OPC software that could not run without the Bay Area. So it’d be interesting to see how ASML tries to navigate the fact they have US content, because they’ve just flat-out said that the 1980i is not restricted. [This was ASML’s initial line right after the regs were released; subsequently on their earnings call, they’ve said that they expect to take at least a 10% hit to Chinese sales which were all DUV anyways.]

Just to be clear: the 1980i is the tool that Doug and I have been ragging about. It’s basically the tool that TSMC used for seven nanometers. And SMIC is freely allowed to import it; that has been the case for the last year.

I wrote a piece in January of this year saying that they were going to hit seven nanometers because they could import this tool. And then, of course, they did import enough and were able to hit seven nanometers and ship the Huawei chip. And they can get to very high production volumes and yields because that is exactly what the commercial industry used.

In fact, they have an upgraded version of that tool — whereas TSMC had to do it with the base version. The 1980i being banned would be a very big step toward closing the gap on preventing seven nanometers. To remind you: the restrictions say fourteen. The fact that they could get all the way to seven — that’s an entire one to two technologies ahead of fourteen. That’s a humongous loophole. If it gets to seven, that would be absurd.

Doug O’Laughlin: If you read the regulation as it currently is, 1980i should be on the export list. That’s something I am most interested in, because that would be a big sea change from what’s been currently going on. And frankly, something that should happen if you just like the results that just came out today.

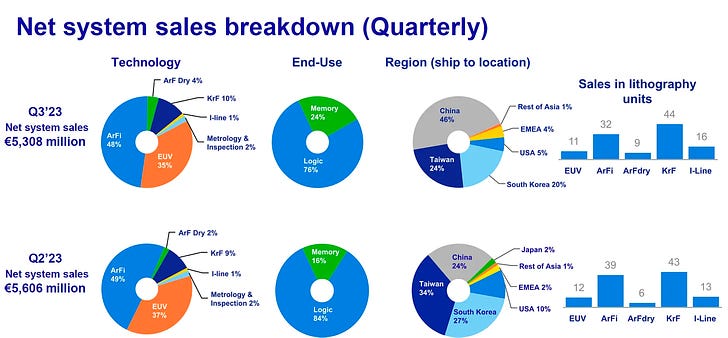

50% of ASML’s shipments for orders in the quarter is China. That’s too much.

They are explicitly trying their absolute hardest to get around what we’re trying to do. And for whatever reason, ASML has been this giant loophole that they’ve been able to drive 1980i shipments through. It just doesn’t make any sense to me.

Jordan Schneider: The question is, “How many of these tools are already in China?” And are the billions of dollars of tools that those “advanced fabs” have already bought going to be able to continue to be serviced by ASML? Is the amount of capex that has been spent on this tool in particular over the past year or so enough to run a lot of wafers in a globally impactful way?

Doug O’Laughlin: I mean, it’s billions, right? It’s a lot. The DUV shipments this quarter alone are probably the size of multiple TSMC fabs. The throughput that is implied could be sixty machines or something. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that there’s so much this quarter, particularly because of the expectation that this was coming. And so of course, they’re like, “Well, why don’t we shove as many in?” Since last year, ASML has had DUV in an essentially hockey-stick upward trend. They’re going to do their absolute best to continue to sell as many units.

I’m particularly frustrated about the DV tool. And I think it’s insane to look at Q3 2023 sales and see the region split: 46% is to China, whereas 24% is to Taiwan. So they are doubling the increase in capacity this quarter compared to Taiwan — and that’s including EV tools.

Dylan Patel: And to be clear, they’re not stopping — they’re only stopping for certain advanced fabs. However, they don’t consider CXMT, SMIC, and other leading companies advanced fabs. It’s the same argument that Jon brought up earlier: why are you giving preferential treatment to equipment companies?

Jon Y: Do we know how much of that region is to Taiwanese companies with fabs inside China?

Doug O’Laughlin: No, we’ve never had that kind of breakdown. This region ships to a location. So these are just the things that go into China.

Also, something we should probably talk about is the new export restriction based on reselling tools. Transferring tools have some license requirements now as well. But the problem is: if you sell a DV tool to SMIC for the lagging-edge, can they use it for the leading edge? Probably. I just don’t see that distinction playing out well. Could you sell a DV tool to a tiny-tier four-fab in China that may sell their DV tool to SMIC under the new export restrictions? I think not — that would have to require a new license in order for it to be transferred. (But that’s also with a belief that China will adhere to the rule of law in terms of these restrictions which is questionable.)

Jordan Schneider: Catching these sorts of company transfers would be very challenging for BIS — good luck, guys. And this is the sort of conversation you guys had about the DUV tools — the fact that you ended up having quarters of billions of dollars of sales over the year and that it took another eight months to write the 400 pages of regulations is a little frustrating.

The proof is really going to be in the pudding if you start to see the subsequent quarters of semicap exports into China decrease, which I think ultimately has to be a part of the KPIs that the American Export Control has set for themselves.

Doug O’Laughlin: So for context: when last year’s October restrictions happened, semi-capped tools tanked down a little bit. Then people realized there were a lot of loopholes, so semi-capped tools into China went up in a straight line.

If ASML is a good indication of anything, China is going to be the largest geography where all tools are going in the entire world this quarter — from Chinese to American to Korean to European tools. We’re watching a supernova in capital formation for these fabs in China. As for the dates: if my understanding is correct, the tools get applied today or maybe in November and the AI one gets applied in November in thirty days.

ASML Needs to Quit Whining

Jon Y: If ASML wants to complain about losing DUV revenue, why don’t they just improve their EUV stuff to actually make it usable, and … maybe ship high NA? Just a thought.

Dylan Patel: Simple! Just figure out the magic technology!

Doug O’Laughlin: But capitalism must ask you, “Why make new thing if you can sell old thing for more?”! Think about that.

Jon: That’s that CFA training right there…

We continue with lobbyist power rankings and Dylan’s predictions about future trends on equipment sales into China.