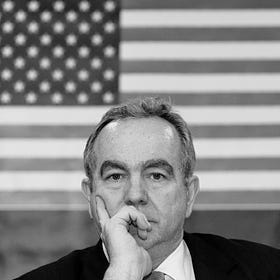

Michael Collins is the acting chair of the National Intelligence Council (NIC). He has spent 28 years in the intelligence community, starting as a career analyst focused on East Asia before moving into leadership roles. He served as chief of staff for the CIA deputy director and worked on modernization efforts in the agency.

We discuss:

How the intelligence community informs high-level policymaking,

Why different institutional approaches are needed to collect intelligence on non-state actors vs nation-state adversaries,

Challenges in assessing China’s technological and military capabilities,

“Narrative Intelligence” and areas where intelligence agencies have a unique edge,

Strategies for improving long-term forecasting and avoiding groupthink.

Intelligence and Capitol Hill

Jordan Schneider: Let’s have you introduce yourself. Can you briefly tell the audience a little bit about your journey through the intelligence community and what the NIC is?

Mike Collins: I’ve been in the intelligence community now for 28 years, and came in as a career analyst long ago after doing graduate work in international affairs.

Most of my career was as a career analyst, mostly on East Asia. I became a manager in various capacities, and worked a bit overseas to get a feel for the mission as well. At one point I was the chief of staff for the deputy director. I was privileged to work on modernization reviews in the CIA.

At one point, I was the deputy director of one of our integrated mission centers at CIA — the East Asian Pacific Mission Center — where I got a feel for bringing together all the pieces of the intelligence world for what the agency can accomplish. Previous to this job, I was the chief strategy officer at the CIA, working for Director Burns on a number of things. In particular, the initiative he put forward to review the structure and posture of the CIA for major power competition at its core and all the different derivative recommendations that came out of that. I could speak to some of that.

Then I got an opportunity to come over to the National Intelligence Council. The National Intelligence Council at its core is the lead representative and producer of the US intelligence community’s overall analytic view of issues in the world. It’s distinguished from all the individual agencies in that we speak for the entirety of the US intelligence community, not one agency in particular, and again, the lead producer and representative of that.

In the spirit of ensuring our policymakers receive the widest, most diverse, and most inclusive view across the community, we take seriously the role we have in bringing in the private sector. We are constituted right now by 18 different programs.

National Intelligence Officers make up the NIC. Those are the senior representatives in each of the regional or functional aspects that we cover in the world. Their task is to be the principal lead in their respective area.

Most importantly, our signature products are the national intelligence estimates, the long-term future anticipatory products of the US intelligence community, looking at key trends and strategic developments in the world, as well as the signature global trends product that’s produced every five years. Now we will be going out to 2045, assessing where the world will be trending then.

In recent years, this NIC has become very busy as well with direct policy support for policy meetings downtown. When there is an intelligence briefing required to start a national security conversation, the practice is to have the Intelligence Community brief an assessment pertaining to that issue. The National Intelligence Council is taking the lead on providing the intelligence on a recurring manner for that, truly at record numbers, historic numbers.

Finally, I would just say our role as the lead analytic representative for outreach and engagement. Kind of what we’re doing actually here to relate more, to inform and to support our government’s conversations with America, frankly, about the analysis we produce and the collaboration we need as well for the use of such analysis for our engagements with partners around the world.

Comparative Advantage in Asia Analysis

Jordan Schneider: You and Kirk Campbell, also a former China Talk guest, are among the few folks who’ve risen to very senior levels of government and have decades of experience engaging deeply with East Asia.

This perspective is fascinating. In the 1990s, intelligence officials who studied the Soviet Union all of a sudden ended up working on Iraq policy. Now, a lot of people who studied the Middle East are involved in East Asia policy. 10 or 20 years from now, it’s likely that we’re going to have a lot more people with deep engagement and experience in East Asia running a lot operations in different regions.

As someone who has been studying Asia since the beginning of your career, what has it been like to watch your region enter the spotlight? What makes your perspective unique compared to newcomers who are strictly focused on understanding the PLA?

Mike Collins: At a broad level, it’s important to reflect on the expertise and experience we have covering what we call, “hard target challengers” of the United States and the world — those countries that are viewed as strategic competitors of ours. We call them hard targets because they’re hard to understand and hard to collect on relative to what we call the global coverage arena. That’s sort of the rest of the world that we have to be conversant and understanding of.

Throughout my initial time thinking of East Asia, I came to appreciate all the more thinking of China as part of East Asia and of course, the dynamics that relate across that region in terms of relationships and influence and standing, understanding the governments of the region themselves and the populations themselves and the relative sort of standing our government has or what we stand for in the region relative to those of a different state, in this case, China in particular.

I would highlight three things in particular over the years that have deepened my thinking, not just in this arena, but also around the world.

1. Over the last couple of decades, we have come to appreciate more the inherent normative roots, if you will, of the conflict contestation we have with the PRC.

This is what the PRC (and under Xi Jinping in particular) defines as a geopolitical competition — they describe it as such themselves.

But when you peel the onion, at its core, it’s a difference between what we stand for, how we govern, and what we advocate in the globe — and what this authoritarian state stands for.

Especially now that Xi Jinping is increasingly doubling down.

We have to appreciate that more, and we have to understand the dynamics within China, not to think of it just as a monolith in terms of the conversations it’s having with its people, its business community, its tech community, etcetera.

Sometimes I’m asked, “When we double down, are you just focusing on China? Does that mean we don’t need to focus on anything else?”

On the contrary — it means we actually have to be better at understanding the rest of the world. What makes the rest of the world tick? Where do these populations stand, as I said earlier, in the global competition? What are the roots of and sources of unrest in the rest of the world?

For the last two decades, the intelligence community understandably focused on terrorism.

Now we’re getting back to thinking more about the study of international relations more broadly in the world.

We have to understand that increasingly all the more certainly apply that in the work we do at the NIC.

The last area is those domains that increasingly will matter for this major power competition. Technology clearly is one, and we all talk about that a lot. Obviously, we prioritize that. Director Burns certainly did when we did the reviews in the agency.

These domains that govern international affairs— we also have to be increasingly smart on, conversant on, and appreciative of the role they play, including through the gray zone. The gray zone is that area within which rivals are trying to compete with the United States without resorting to direct major power conflict, but also still right of what we consider traditional or accepted forms of statecraft.

Those areas, I’ve appreciated all the more, beginning with my works, if you will, on East Asia and thinking of East Asia itself as a region and a collective, and now thinking more broadly in this capacity, applying the same to the global landscape.

Jordan Schneider: There is an ideological competition with ISIS, but we aren’t super worried about their quantum advancements.

Reflecting on your time doing this reorganizational work in the CIA, what needs to happen at an institutional level in order to effectively analyze a country like China as opposed to the Taliban?

Mike Collins: I was asked a very similar question early on in the process of the review. In any strategic approach to reform, you try your best to parsimoniously get at what at its core will most improve your strength. When I responded to that question, and I still do hold to this today, it’s about relationships and collaborative, more integrated relationships, and leveraging capability where it exists.

I’m a career CIA officer. One thing I really appreciate when I think of the agency and its five directorates — that place is really strong in leveraging all of the unique capabilities and authorities that each of those directorates have, whether they’re as service providers or as their mission executors.

I’ll speak here for the NIC. The National Intelligence Council is not an entity unto itself. We are actually a relatively small unit. We probably only have around 100 analysts in the National Intelligence Council, give or take, covering the entire world. We succeed to the extent that we leverage the unique strengths of analysts across the entirety of the IC, as well as increasingly experts in the private sector, be they in academia or in the business or commercial sector. This is a more federated approach to taking and utilizing capability where it rightfully sits.

I say that in part because those analysts, for example, who are sitting in one particular area, bring to that analysis something very unique because they’re part of something or living in something that not everybody actually does. If you think of an analyst who works for a company whose job it is to make money selling products around the world — they’re thinking differently about their risk analysis. I could apply the same to the analysts in the State Department, the analysts in DIA, the analysts in CIA, each of which are stronger in a unique way because of where they actually sit. We have to leverage that more.

Again, I would say at its core, on the various reviews I’ve been a part of, if I had to distill it down to one thing that was probably most critical, it wasn’t necessarily about new structures or necessarily new positions, but can we maximize the strengths that come from a more, if I will, federated, but at the same time more collaborative and integrated effort, whether that’s on the responsibilities and mission execution capability of a unit or its enablement, be it substantive or be it, say, in the training or workforce or governance domain.

Jordan Schneider: I want to talk about the comparative advantage of the intelligence community, both on a domain level and a time horizon level.

Let’s do domain first. You mentioned I can totally see that IC would have an advantage in understanding some particular artillery piece in an adversary’s army, just because there’s no other body in the private sector or academia that would spend the time or money on that.

But when thinking about understanding the Chinese economy, the advantages you get from secrets insight are less obvious, to me at least. How do you think about allocating resources? What do you guys think you can and will continue to always be able to do better than other agencies? What areas benefit most from outside perspectives and voices?

Mike Collins: I love the question in a couple of ways. Let me set the table first by stressing one of the things I’ve learned in my career — the increasingly important and yet unique role that intelligence itself plays for our security as a national security asset.

It’s noteworthy that our national security strategy now includes references to intelligence as one of those categories of national power.

Heretofore, most national intelligence security strategies would reference military, economic, and diplomatic power — those normal, traditional elements of power. But now we’re talking about intelligence itself.

When I talk about intelligence, I mean that in its purest literal sense — that is, I’m more intelligent and smart about something than I was a year ago. Even in a competitive sense — am I more knowledgeable about this issue than my adversary?

One of the things we try to take advantage of to be competitive and what the intelligence community can provide are our relationships, our partnerships around the world, and increasingly our deeper partnerships with the private sector and the commercial sector. We benefit from the fact that the United States is as big as it is, and we’re as present as we are around the world. We benefit as well because we have responsibilities, therefore, unlike any in the world, to stay on top of those same issues.

In so doing, you have to have eyes on a lot of issues around the world to ensure you’re providing maximum coverage for the policymaker. But in so doing, you’re learning something beneficial that will inform the analysis we produce.

We know there will continue to be an exquisite need for the hardest of the intelligence we can collect that gives us a unique perspective on the motivations and thinking of our adversaries around the world. Increasingly, as these adversaries are clearly trying to cooperate even more together, we will need that. But even to that end, to be successful, we know we need partners and avenues to allow us to accomplish that effectively.

At the same time, we know increasingly, for all the expertise and insight that can be acquired and investigated openly in the open source arena, we would be hurting ourselves if we weren’t doubling down on that as well. We have to leverage, and we are leveraging all the more what academics are studying, but even more so what scientists are learning from what they’re doing, what commercial practitioners are learning from their experience, what the financial community is learning as we take advantage of the globalized arena.

The last point on this I would highlight for the NIC as an example. We recently launched this new external research council as a council for the council effectively, whereby we’re maintaining on a recurring way experts in all of our different portfolios, whose job it is effectively to help us stay ahead of the research and the understanding, the expertise that’s being built in all our portfolios that we may not simply have the time ourselves to stay on top of as much. But the idea there is we’re acquiring and collaborating on collective analysis. I know we’re benefiting as well those on the outside who have an interest in studying the same, whether they’re in universities or in the private sector. Again, taking advantage of what work is already being done in many areas.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on this one more second. You alluded to a few things — leadership intentions, hard power, and military capabilities are probably the two that most obviously come to mind as the things that no one is ever going to be able to do outside, better than the US intelligence community. What are the other things that you think are always going to have to sit within the intelligence community?

Mike Collins: There are a number of things that will always have to sit in the intelligence community. As you well know, we don’t speak about sources or the methods and the means by which we acquire what we do. There are second or third-order derivative aspects of things we do in the intelligence community that obviously we don’t speak to for the reasons I just said.

But on top of what we might be able to uniquely understand about the motivations and intentions from centers of power around the globe, I’d probably add to that — this increasingly challenging geopolitical landscape around the globe is to some extent different than the Cold War. Big countries around the world are not necessarily taking sides, nor are we asking them to raise their hand to choose sides in this sort of geopolitical competition in that way.

Related to an earlier point about intelligence and the national security strategy, a lot of what we accomplish in the world and understand about the world does happen quietly. The disposition of foreign partners and governments around the world to work with us — not just the intelligence community, but the US government — is often gleaned uniquely from what we know our partners around the world are potentially willing to do for us in more sensitive areas.

I do think that will be an increasing source of unique expertise that we do have. Again, as we appreciate the more behind-the-scenes, sort of quiet ways in which we’re trying to form and collaborate.

It’s just not going to be as likely that people will be raising their hand and voting between one side or the other. But let me add one more point. As clearly as I know we can acquire and understand and think about our leaders in various ways from what we uniquely do, we are also reaching out to look at other ways by which we get indicators of intent — through behavior, sentiment, narratives, public conversations leaders are having with their individuals, through what they’re doing with their economy.

You know this just as much as I do — somebody on the outside can make powerful judgments about what the intentions or readiness or inclination of a country might be, based on other indices they observe in the public arena.

Those are things that are increasingly important for us as well, because they sometimes can illuminate and provide strategic warning of where something might be going, even if it can’t provide the proximate sort of indicator of what time and space that might occur within.

Jordan Schneider: What can The New York Times and The Economist not grasp that you can? Does the edge of the intelligence community hold up over time?

Mike Collins: You’re not going to find a report today that says what will the global order look like 25 years from now. But again, our job is to put together a set of variables, a set of drivers that determine where that might be going, one of which is clearly the motivations and plans of countries around the world. What are they intending to accomplish? What are their strategies gearing them toward? What do they tell themselves internally about what their metric of success is 10, 15, or 20 years from now? The motivations of countries, where do they want to be? That piece is very critical.

At the same time, of course, as another variable we look at capability, do we objectively believe they have the capability to get to where they want to go? And to the same, do we understand? Do we believe what we objectively say about their capability is what they also agree their objective sense of their capability is? The latter is something, again, we might more uniquely understand than somebody on the outside potentially might. But you can glean that as well from what they say publicly, often to their audiences.

The last variable in that same forward-looking anticipatory analysis is what’s the rest of the world doing? That permissive environment. Its motivations, its capability. But what’s that arena look like, is it vulnerable? Is it permissive? Is it resilient or not? Is the rest of the world responding differently?

Those are all areas that we have to look at when we do our forecasting. But you’re right in saying that as we get further and further ahead, the less arguably relevant, although not completely irrelevant, is the unique information we have on what countries are planning internally.

Intelligence and Long Time Horizons

Jordan Schneider: I’m interested in the longer-term perspective, particularly from the standpoint of capturing policymakers’ attention. If you drive down to 1600 Pennsylvania and say, “We think Putin’s going to invade Ukraine next week,” that’s obviously something people will wake up and pay attention to. But you have to think about the long term as well. How do you approach the challenge of selling the idea of 5, 10, and 20-year horizons to the people who are spending money and making decisions today?

Mike Collins: I’ve thought a lot about this. It’s a great question. I’ve been honored to brief various senior government officials and leaders. That question often comes up when considering whether to provide analysis beyond the four or eight-year cycle. My response is, to the point I just made about the strategic trajectory 20 or 25 years from now, what the world will look like in terms of the balance of power between China and the United States — to the extent you can be objectively accurate in what you say, “When historians look back 20 to 25 years from now, they will examine decisions made on this particular issue, at this particular period, to determine what was critical to the trajectory.”

When we do national intelligence estimates or global trends, we prioritize those factors in our estimates. Even if we’re estimating 10, 15, 20, or 25 years out, we owe it to every policymaker to identify the factors most influencing outcomes, and particularly, what can be done about those factors now. When you approach it that way, you get traction and a response.

The last point is that you must be clear about your metrics of analysis — the indicator set. If we see development trending in certain ways, we should constantly revisit it. Whatever the issue might be, we should establish a framework. Every year we’re seeing if it’s moving in expected directions or not, objectively suggesting whether the forecast we warned of or anticipated may be happening. This keeps you in conversation with the current group, not just writing for those who may come into power two decades from now.

Jordan Schneider: We have an upcoming interview with Kumar Garg, who spent eight years at the Office of Science and Technology Policy for the Obama administration. We discussed getting policymakers focused on drivers of long-term competition. His point was that in the White House, they had 20 people focused on some marginal tax rate policy and only one or two focused on high-skill immigration, which plays a big role in the future of American innovative capacity. My initial thought was that it makes sense because people vote on their tax rates, and politicians have to get reelected.

Broadening that insight to a systems competition level, we could have a long discussion about the extent to which China is actually long-term and strategically minded. The fact is, America has really done this in fits and starts over the past 75 years. Even looking at the Cold War, there were many different directions that governments went in defining long-term competition and what policies they thought would lead the Cold War to end positively. Do you have any thoughts or reflections on this?

Mike Collins: In the intelligence community, we don’t comment on or inform what our leaders decide from a domestic political standpoint. We recognize our elected leaders have other factors that weigh into their decisionmaking. Our responsibility is to lay out the national security implications of issues around the world and what can be done about them. It’s then up to the decision-makers to consider all factors.

If we’re not effectively drawing attention to these dynamics that we believe are truly significant for national security, we’re probably not doing our job well enough. If we really think it’s that critical, we should be doing more about it.

One of the things I admire about what Director Haynes and ODNI are doing, and we’re a big part of it, is their transparency initiative. We are more openly sharing our judgments and views of the world with the public. You see this every year during the annual threat testimony, and increasingly on our webpage where we release analysis for public consumption.

We have a responsibility to inform the larger narrative about what matters in the world if we’re going to be effective. That’s part of the reason for the transparency initiative — to open up and engage in a broader conversation with the larger American and global audience about what we see in the world. We do this hand-in-glove with policymakers.

We also do this because we need to be challenged. We need talent and insight from the private sector, and we need to avoid groupthink. We take seriously our responsibility for modeling objective critical thinking not influenced by politics, to ensure that what we write does not look like it was written specifically for a political or policy agenda.

Jordan Schneider: Staying on the domestic theme for a moment, let’s consider the concept of net assessment. Some of the CIA’s most famous accomplishments over the ’70s and ’80s with respect to the Soviet Union were doing this long-term economic analysis and grasping — way before much of the broader community — that the Soviet Union was growing a lot slower than maybe even someone in the Kremlin understood.

When doing net assessment, it’s fine for you to compare Western military capabilities to Chinese ones. But as you’re thinking about other domains of competition, like emerging technologies or international trade and investment, there’s a unique handicap in not being able to comment directly on American capabilities and policy options. How do you think about getting around that challenge?

Mike Collins: That’s a great question. Across the Intelligence Community, we’re looking more seriously at how we understand and can work with non-state actors or entities. This relates to domains that increasingly matter for raw US geopolitical national security, but also transnational security in the global commons — climate, health, and disease. We know we need to be doubling down on engaging with and understanding these arenas and the experts in them. We need their talent, expertise, and tech. We also need to think about the threats they themselves are under because they matter increasingly for national security beyond the traditional military domain.

To that end, we are starting to flex our muscles, using the net assessment concept, sometimes literally, sometimes metaphorically, to look at those other domains. We’re examining the balance of relative strength in techno-economic categories, media, education, science, and all those different areas of international affairs that reside outside of traditional state-to-state diplomacy and are in the private sector arena.

Obviously, we do not collect specifically on the United States, but to better understand the severity of a threat that would come from an adversary being more dominant in microelectronics, biomedical, media, or any other issue, we do need to understand and be conversant on the relative strengths and resilience of the United States in that same area, as well as our partners around the globe. This helps us truly understand the threat that would come from another country, an adversary, or a geopolitical challenger being more dominant in that space than they currently are.

It also informs our domain analysis, helping us step back and think about what determines success in these areas. There’s a lot of talk about AI, for example. As you can imagine, there’s a lot of work being done on the relative strengths of various ecosystems in the AI space.

This net assessment idea is increasingly what folks should start to hear more from us. We obviously have to do it in partnership with experts outside of the US government to be effective at it.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s come back to this idea of transparency. It’s one thing to write and publish more unclassified material about long-term trends and threats, but it’s another to do what we’ve seen over the past few years, particularly in the lead-up to the war in Ukraine. We’ve also seen this with the PLA purgings and the water and rockets arc that rippled through global collective consciousness over the past year or so. How do you think about those types of disclosures, maybe in the China context in particular?

Mike Collins: I’ve come to appreciate what I sometimes call “a new INT,” — NARRATIVE INT. Narrative warfare, information warfare — sometimes people refer to it as narrative contestation. There’s a lot of talk in the national security conversation lately about misinformation and disinformation in the global arena. Frankly, that’s both a supply and a demand problem.

We look at, investigate, identify, and talk about the threats our adversaries are attempting through the use of misinformation and disinformation. What President Putin did before the Ukraine operation was an act of misinformation, trying to disinform and misinform about what was going on in Ukraine. The same is happening in China. The conversation the government of China is having with its people would arguably benefit from some rigor in terms of separating fact from ideology.

When you step back and appreciate what’s happening through the use of social media and what it has enabled relative to what traditional media can provide in a more credible sense, I worry a great deal not just about the provision of misinformation and disinformation, but increasingly about the resilience of human beings to the truth - what the truth really is, what it represents, and whether people care about the truth.

One of the realities in this great power competition we have with geopolitical challengers is the difference in our relationship with the truth. Unlike us, our authoritarian rivals are often not accountable to the truth. Increasingly, as you look at what they’re doing to double down on their security architecture and what they’re doing to surveil and control narratives at home, in many cases, they fear the truth for what it represents in terms of things that have happened in their own country or what’s really happening broadly around the world.

I think this is going to be an increasingly powerful means through which we compete and succeed globally. It’s not just a one-off release of information. We need to call certain things out, but I think to the extent that we’re seen as more credible and impactful, we should be driving more open conversations about narratives that are out there that we can say, with objective, empirical evidence, are just not true.

We should think about the relationship between the state of an authoritarian competitor and its people. What do its people fundamentally believe about what’s true, for example, about what happened with COVID? We talk about vaccines and the cooperative approach or lack thereof towards sharing information pertaining to that disease. You know this as well as I do — what that doctor in Wuhan was trying to express. The state of China did not want the truth to be exposed, and we should reflect on that.

Jordan Schneider: We’re recording this on July 26, a few days after Biden gave his “I won’t run for reelection” address. One of the lines that really stuck out to me was him saying, almost as an aside, “When I came into office, the conventional wisdom was that China would inevitably surpass the United States. That’s just not the case anymore.”

When I reflect on the past five years of that narrative shift, I don’t think that was some CIA operation or psyop to convince the world of this. What ends up changing people’s minds are economic growth rates and how different countries relate to each other. You can only play so many games around that in altering people’s perceptions.

You mentioned the COVID thing, and hopefully this wasn’t your fault, but I have to bring up the article in Bloomberg which related a story, I think coming out of the Defense Department, where they paid for information operations in Tagalog saying that the Chinese vaccine was going to make your kids autistic or something.

My piece of advice to you, Michael, is that I think you’re almost underrating the power of truth, accuracy, and empiricism to win out over the long term. You can only really play games a little bit on the margin, but I don’t think the Chinese people are stupid. I don’t think the American people are stupid. I don’t think folks in the rest of the world are stupid. A strategy that bases your information operations agenda around trying to pull the wool over people’s eyes is not one that’s going to serve you well over the long term.

Mike Collins: I’m going to challenge that, Jordan. I’m not talking about pulling the wool over somebody’s eyes — to the contrary, I’m speaking about exposing the facts. I’ll be the first to admit we’re not always going to be right, but if we’re seen as trying to expose credible facts about something, the more successful we are in getting those facts out and understanding them over time, the better. We leave it to others to debate that.

I’ll just highlight the one fact I conveyed before — that poor doctor was trying to express that something was happening in Wuhan, and he was prevented from doing so. That’s a fact. That’s an example of the differences between our norms and values and freedoms of expression, as well as the liberties that we stand for relative to what the state of China stands for.

That’s an example of a fact which, not to say it was the reason millions of human beings around the world died, but it was a reason for how quickly that disease started to spread before we got our hands around it. Maybe it was a week, maybe a couple of weeks. But again, it’s a fact and a representative fact about the difference between our relationship with the truth and their relationship with the truth that we should reflect on and be conversant about.

Jordan Schneider: Reflecting on the past few years of America and strategic transparency, this was clearly not your decision to basically stop talking about the balloon. More broadly, not everyone has bought into this line of logic. Could you talk about when it isn’t necessarily in America’s interest to air the financial or extramarital dirty laundry of strategic adversaries’ leaderships, for example?

Mike Collins: In studying the impact of objective narratives around the world and what tends to stick, often it’s when you connect with something that’s important to another human being or polity around the world. If all we’re doing is being seen countering something or denigrating or criticizing something, that’s not good enough. There’s a role we can play in objectively trying to drive an understanding, as empirically founded as possible. People will always challenge it, and we all have our warts in our respective systems around the world. But truly, the benefits of a liberal democratic approach to governance and what we actually stand for, as much as we trip and stumble over ourselves as we attempt to adhere to those principles.

In many cases, a more proactive conversation about what is better for not just national security, but transnational human security is needed. One of the things I worry about in a forecasting sort of way, getting back to the China conversation — we’ve seen it all the more in recent weeks and years, is Xi Jinping doubling down on an autarkic approach to technology in the interest of self-reliance and protecting China from his clearly articulated definition of strategic industries they want to be the leader in.

Are we potentially moving into a bifurcated approach to technology and even science? One of the challenges we face is as the world is wrestling with issues for which we need cooperation, we’re at the same time contesting over the norms by which those issues are being explored. It’s about proactively driving a conversation about what is best for solving a problem, as opposed to just being seen as criticizing somebody to knock them down.

Jordan Schneider: I want to reflect more broadly about the role of intelligence. In the closing of his book Engineers of Victory, which looked at different operational campaigns over the course of World War Two, Paul Kennedy said initially he was going to have a whole chapter on how to win the intelligence war. But the more he looked at it, the more he saw over the course of World War Two that the study of intelligence over that period was like a whole lot of study of failure.

Broadly, does any of this even matter in the end? If national power is just downstream of economic growth and productivity growth and military capabilities, can a clever memo from an intelligence analyst really bend the arc of history?

Mike Collins: It’s not that easy if we just put out a formula and an algorithm to say what the future forecast of our economy will be relative to some other country.

Relationships and intellect do matter, and agency, frankly, matters. I’ve studied different theories of international relations from the most structural to the most constructivist, and the differences between what the structural forces will bring about inherently, as opposed to looking bottom up at what constitutes the agency of various actors and the decisions they make within the system.

One of the techniques we apply is the art of the alternative futures tool, whereby you begin with an outcome and then we try to talk about how you can get there. Classically in the intelligence community, we want to begin with the worst-case outcome.

But what I challenge the analysts to do is to pick an outcome where we win. The world trends in a way, or the issue trends in a way, that the United States and our partners come out on top and then work it back as diagnostically and precisely as possible for all the ways in which we could see this vector.

There are many unanticipated events that could happen. Weather events, natural disasters, tsunamis, are great case studies from what happened in the South Pacific years ago, not just the one in Japan. The impact our response to that actually had on our positioning in Southeast Asia for how the US military, for example, came to support that same be true in Japan.

We do these global trends forecasts, and we’re very honest and humble. We don’t have the magic formula, but we try to apply both. We apply what the structural data says as you apply them to the algorithm. But then you have to look back — what are those key decision points along the way? Where do individual leaders particularly matter?

Understanding Xi Jinping — he’s been arguably one of the most disruptive figures in what was happening in the US-China relationship and more broadly, of China’s place in the world.

He’s the one who said, forget about hiding capabilities and biding our time 韬光养晦. He said, now is our time to be 有所作为.

Leaders and when they come up can in fact matter.

Challenge ourselves, and certainly, be humble in the predictions we make. But at the same time, I don’t believe that it’s as easy to just say, well, look at the balance of economies would go forth. The relationships that exist among various countries and non-state actors in our countries increasingly matter. What individuals themselves think about these issues, as I said earlier, the individual will increasingly matter to a lot of issues going on in the world. As we talk about contestation in the gray zone and other areas.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s close maybe on a call to action or two. What are the biggest open analytical questions you see? What do you want to read more papers about? How can folks get in touch?

Mike Collins: Thanks for the advertisement. We, especially in the National Intelligence Council, are open for collaboration. That’s my opening pitch. We convey this through venues like this. We convey this through various addresses we have. We convey this to the External Research Council. I just described another venue we have where we’re offering up to help others.

We have a lot of talent in the United States and around the world who want to work in the intelligence business. We also have a lot of partners who work in the private sector who are studying something for some other reason that we may be able to help them as well in a collaborative way. As universities are training students who might want to get into the intelligence community business, we can help them to think through the programs they’re teaching and the things they’re studying that benefit us but also showcase our work out loud.

There are three areas, as I think about things that I particularly want to double down and think about where work needs to be done. Let me be as precise as possible:

We need to look at our geopolitical challengers, our geopolitical revisionists, trying to change the world in a different way than it currently is, in understanding them in greater detail than as a monolith. We should not just think about them as a unitary state and the leader of that state. Every country around the world has different views and pressures within them. At the end of the day, these heads of state are ultimately, in various forms, to be fair, politicians. They’re responsive to something at home that they’re probably most worried about and most focused on. We need to think more about the conversations that are happening between those leaders and their citizens and their populations in getting at potential areas of dissent and disagreement that may not show themselves as evidently as we expect in the form of, say, protest. When money moves, when people leave, when people are laying flat, that suggests some degree of disagreement or dissonance, at a minimum with what a state is providing.

Gray zone activity. This landscape is being determined. This contest is happening not necessarily as much as we warn about militaries fighting militaries, gray hull ships on gray hull ships, nor is it happening in that legitimate diplomatic, political, economic, above board, international institution governed arena. It’s happening increasingly in that area for which norms have not been established, be it in cyber, be it in foreign malign interference, technology contestation, and the private sector is in the middle of that. We have to appreciate that and study that all the more for all the reasons I said.

We in the intelligence community and with the collaboration with those on the outside, we’ve got to go beyond thinking about national security in its traditional, kinetic sense. We have to think about what determines the commercial and business success of entities in the international arena, and understand and appreciate that is the role of business and the role of commerce in international affairs. Because ultimately, if the companies of one ecosystem are thriving commercially and from a business standpoint, it’s not just from a profit standpoint, but increasingly, from a strategic standpoint, that is another area that we have to broaden our aperture and our appreciation for what national security really is.

Jordan Schneider: How should our readers reach out to ODNI if they want to chat?

Mike Collins: Reach out through our ODNI website.

Jordan Schneider: What do you think about the Cold War analogies for the situation between the US and China today?

Mike Collins: I don’t know if the entirety of the national security community has sort of come to grips with this issue in some ways, but there are parallels to understanding lessons from the Cold War confrontation when we speak to the normative and the ideological underpinnings of it and kind of what we’re facing now with China — not China itself, but the Communist Party of China. For what this leadership has been espousing and advocating for and in their own writings when they talk about what this China is trying to accomplish around the world.

The term [Cold War], broadly speaking, refers to a contestation, a challenge within which one country is using all elements of power to achieve something in a geopolitical sense at the end of the day without having to go to hot war. We see this in the descriptions and the narratives of what the leadership under Xi Jinping is trying to broadly accomplish in terms of China’s place in the world. I’m not saying they’re looking for a hot war. To the contrary, they’re trying to compete with us and challenge our standing without having to get there, but utilizing all purposes of power.

This is as much a competition over the norms, the values, the liberties we stand for relative to the norms and values that our authoritarian rivals stand for.