What role have patents played across history in building national power, and how in the 21st century have the US, China, and EU played their cards differently with respect to IP?

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed Adam Mossoff, professor at the Antonin Scalia Law School at GMU.

Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or check out the YouTube video.

We explore…

How the patent system has shaped American society since independence,

The extent to which patent policy caused the great divergence between China and the west,

Whether Elon’s misunderstanding of patents will become the dominant attitude of the second Trump administration,

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) and other threats to the U.S. innovation ecosystem,

How to reconcile China’s IP theft with robust domestic patent law,

What the U.S. can do to facilitate innovation while competing with China in emerging technology.

Thanks to The Innovation Alliance for sponsoring this episode. The Innovation Alliance is a coalition of research and development-based technology companies representing innovators, patent owners, and stakeholders who believe in the critical importance of maintaining a strong patent system that supports innovative enterprises of all sizes.

The Right to Innovate

Jordan Schneider: Let’s go back to 1787. Why was patent policy so uncontroversial that it was written directly into the Constitution without any debate during the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia?

Adam Mossoff: Many people don’t realize patents are in the Constitution. It grants inventors, creators, and artists the power to secure exclusive rights. While it doesn’t use the terms “patent” or “copyright,” the basis for such rights is Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution. This marked the first time in human history that protections for intellectual property appeared in a country’s founding document.

Several core reasons explain this inclusion. The Founders recognized that creators and innovators morally had a right to the fruits of their productive labors. Following John Locke’s notion that we have the right to mix our labor with things in the world to create property, they applied this principle to innovators and creators. George Washington was what we’d now call an angel investor. He invested in steamboat inventors in Virginia.

Jordan Schneider: But Adam, what were his returns like?

Adam Mossoff: Not very good, from what I understand.

Noah Webster, of Webster’s First American Dictionary fame, traveled to Philadelphia to explain to the Constitutional Convention how he struggled to sell copies of his dictionary due to varying copyright protections across different states. He needed national protection for his rights since he had a book to sell nationwide.

Robert Fulton, famous for his steamboats, demonstrated some of his early prototypes to the delegates as well. They took a break from the convention and went to the Delaware River to watch Fulton’s prototype in action.

The delegates were intimately aware of these issues and understood their importance, especially for a new country lacking an industrial base. The nation was primarily agrarian at the time, and the Founders recognized that patent rights would be key to growing America’s innovation economy.

Jordan Schneider: Many funny things come out of that origin story. This is downstream, of course, of people being upset with England, the first modern country to set up a version of this patent system. The royal prerogative was baked into the whole British ecosystem, with patents being granted at the whim of the Crown and assigned to one person — and the Crown never had to pay any royalties. It was much less comprehensive and more arbitrary, though better than whatever they were doing in the Frankish kingdom.

Webster was an early patent lobbyist — congratulations, we have a rich legacy here. The inventors showing up to do tech demos in Philadelphia is like Sam Altman going to D.C. the month before GPT-4 comes out to tell the U.S. government how much AI will matter to America.” Some things never change.

Now we have this policy where the Constitution says intellectual property is actually property and should be something you can monetize. How did that play out in the Republic’s first decades?

Adam Mossoff: Before I answer your question, I’d like to note something about the inventors at the Constitutional Convention. The Founders were really sensitive to and aware of the abuse of government monopolies by the Crown and England. They recognized that these patents weren’t monopolies.

The copyright and patent clause, which authorizes Congress to secure exclusive rights to inventors and creators for a limited time, is the only place in the Constitution before the Bill of Rights where you’ll find the word “right” used. When they use the term “exclusive right,” that means property right. President Washington, in his first address to Congress, called for enacting copyright and patent statutes. Congress did this with the Patent Act of 1790 and the Copyright Act of 1790. These were among the first pieces of legislation Congress enacted, because they were recognized as absolutely fundamental to economic growth and property rights more broadly.

They secured these not as royal grants or gifts from the Crown, but as property rights. This meant inventors could enter the market, make transactions, and commercialize their work — just as people commercialize property rights now by selling houses, computers, or renting rooms. Inventors immediately began engaging in what we now call licensing.

With licensing, inventors could invent without manufacturing. That enabled them to divide up the labor and specialize.

Patent owners invented what we now call the franchise business model — an intellectual property licensing business model. While we associate franchises with fast food like McDonald’s or Wendy’s, it’s actually an IP licensing model where the owner licenses others to manufacture, run, and sell products. Samuel Morse did this with the telegraph and Morse code.

Charles Goodyear did this when he invented vulcanized rubber — he has no affiliation with the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, which was created 40 years after his death and precipitated a trademark lawsuit with his family over his name. Goodyear was just an eccentric inventor. He wrote a two-volume book on all the cool things you could do with rubber — you can make boats out of it, you can make shoes out of it. Then to prove his point, he had copies of this book bound in rubber. He didn’t want to be a manufacturer, he wanted to license other people to make these products.

This quickly distributed these innovations into the marketplace, incorporating a lot more people in the process.

Patent licensing democratized these inventions, leading to an explosion of new commercial products and services from the United States in its first 50-60 years.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s underline that for a second. The British model required the Crown to decide, and if you got the patent, you had to be the one to make and sell the product. The problem is there aren’t that many people like Elon Musk — we’ll get to him later. Not many engineering geniuses or tinkerers, county clerks and such, also have that rapacious capitalism gene to build factories, empires, and sales teams.

In the late 18th and early 19th century, the American model allowed you to get rich and spread your invention across the country and economy more broadly without needing to be blessed with both engineering genius and business genius.

Adam Mossoff: Perfectly stated. Abraham Lincoln famously identified the U.S. patent system as one of the three great achievements in human history, the first being language and the second being the written Constitution. He said the patent system “added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius.” Lincoln knew of which he spoke — he’s actually the only U.S. President to have received a patent, which was for an invention he created before his presidency, in 1848.

Jordan Schneider: What was Lincoln’s patent?

Adam Mossoff: It was a method for lifting boats over sandbars and other obstructions in the Mississippi River. It’s unclear whether it was actually deployed or if he made any money from it, but Lincoln also worked as a lawyer representing other patent holders in Illinois. He represented Cyrus McCormick, who invented the mechanized reaper — the first true labor-saving device in human history. It dramatically increased the efficiency of food production and proved Malthus wrong. Food production went through the roof after the invention of the mechanized reaper. Lincoln represented McCormick in many lawsuits against infringers of his reaper patent. He knew the patent system very well.

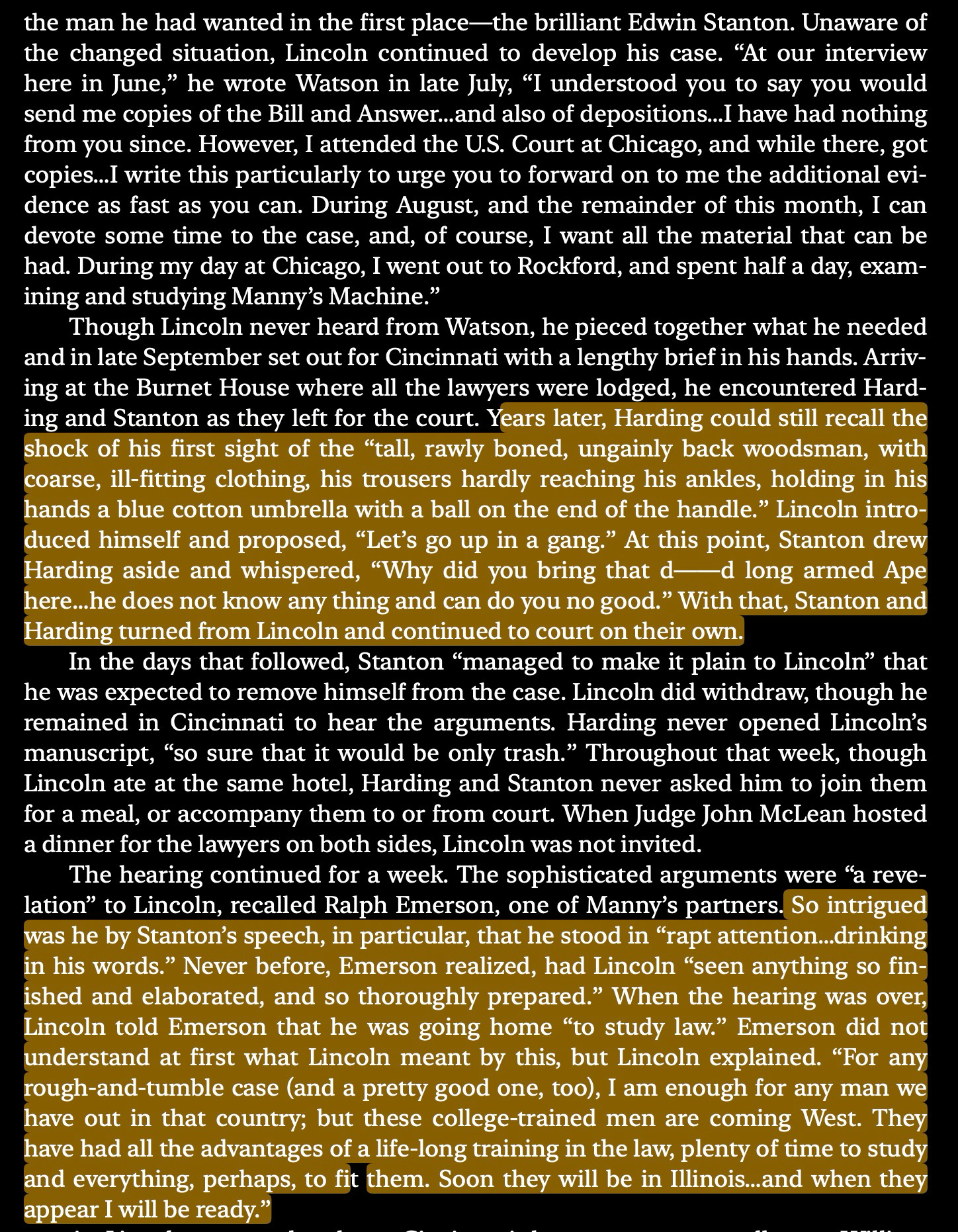

Jordan Schneider: Coming out of paternity leave, all I did was read Civil War history. There’s this incredible moment — example #574 of why Lincoln was an incredible person. He got onto this McCormick case, which was going to be the biggest case of his career. The case gets transferred out from Illinois and then McCormick decided to bring in some big guns from the East Coast who had actually gone to law school. Edwin Stanton shows up, then the hottest lawyer on the planet. He takes one look at Lincoln, who’s gangly and wearing tattered clothes, with his messy 400-page brief, calls him a “damned long armed Ape” and literally doesn’t acknowledge throughout the entire case.

Lincoln’s takeaway from that incredibly rude and disrespectful experience wasn’t resentment, but rather, “Oh my God, I now know what it’s like to play in the big leagues. I need to go back and up my game. I’m thankful for this opportunity to have been the equivalent of an unused pinch hitter on a World Series baseball team.” The fact that he later appointed Stanton as his Secretary of War 15 years later shows his incredible magnanimity. So yes, in my book Lincoln gets to be on Mount Rushmore even though he didn’t make money from his patent.

Adam Mossoff: Those people’s ROI is that we have an amazing country that survives incredible ups and downs.

Jordan Schneider: He gets credit for all the GDP growth post-1865.

Adam Mossoff: Yeah, I mean, he saved the Union. Kind of a small thing.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s come back to Lincoln’s idea that the patent system added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius.

We did an epic four-hour, three-part show with Yasheng Huang a few months ago. Professor Huang argues that one of the key mistakes Chinese civilization made was that the exam system, starting in the 700s, stripped out all the economic returns and societal esteem from doing inventions. Conversely, during the Industrial Revolution, tinkerers in the UK and the U.S. became rich and famous for doing science — which hadn’t happened for basically all of human history before then.

Adam Mossoff: It’s a fascinating phenomenon. China was incredibly inventive — they invented paper money, gunpowder, one of the first modern massive fleet ships, incredible ship technologies, the abacus, and many other things. But then invention shifted to the West, to Europe, and eventually to the United States.

Today we distinguish between invention and innovation because humans are naturally inventive. People invent for all sorts of reasons — prestige, personal interest, joy — but inventing something in your lab or garage is not the same as innovation that’s actually used by consumers, mass-produced, deployed in the marketplace, and sold through stores or over the internet.

That was the key feature in the United States in recognizing patents as property rights, which serves both a direct financial interest and a democratization function. Anyone can invent and get this property right, just as anyone can be a farmer, worker, or podcaster if they choose that career. Property rights serve as the basis for entering contracts and deals to commercialize, engage with manufacturers, and create profit while consumers get the product in the marketplace.

Jordan Schneider: There’s this American national stereotype of a nation of pioneers, self-willed, doing your own thing. The UK stereotype is the British Academy of Sciences, which is more centralized. Yes, in the early years of the Industrial Revolution, you had this very distributed system with local inventors, but pretty quickly you start to have a more aggressive caste system and hierarchy in science. What’s your take on institutions versus national character when it comes to the American story of engineering-based businesses in U.S. History?

Adam Mossoff: It’s a great question. There’s a tendency to be reductionist about things and say it’s all one thing — nature or nurture — but why can’t it be both? It’s more of a symbiotic relationship between strong intellectual and cultural norms about individualism in our society, about individuals pulling themselves up by their bootstraps, as they said in the 19th century.

Many examples illustrate this. Charles Goodyear, Cyrus McCormick, Samuel Morse was a professor of art at NYU when he invented the electromagnetic telegraph. Samuel Colt whittled his first wooden version of the Colt Revolver as a shipmate. Dr. Leo Baekeland was a well-established, famous chemist in Europe who immigrated to the United States to continue his chemistry experiments. He became famous as the inventor of synthetic plastic, patented around 1906, and trademarked as Bakelite.

Elias Howe, who invented the lockstitch — the key technological feature of the sewing machine — was so destitute and had no formal schooling that when Isaac Singer infringed his patent with the famous Singer sewing machine, Howe had to get an investor to fund his lawsuit by selling a security interest in his patent.

These weren’t aristocrats or people from highbrow society. They weren’t rich or socially privileged, yet they became very successful and many became household names through this system of property rights and cultural norms. It’s a combination of law reinforcing and supporting cultural norms, while those cultural norms drive the reason we have these laws in the first place.

Jordan Schneider: For those interested, I would highly recommend the book “From Know-How to the Development of American Technology” by Elting Morison, published in 1977. When people recommend books from the 1970s, you know they’re good.

Morison does an awesome job covering railroad and canal innovations, as well as the early years of MIT when it was very much a trade school. The contrast was with Harvard, where professors with doctorates maintained a gentlemanly aesthetic of staying far from the market. Meanwhile, MIT professors all had companies and were consulting for railroads and steamship firms.

The thesis of the book essentially argues that by having this engineering culture, with MIT being the most prominent institution after West Point, and being very engaged in commercial markets, the invention-to-innovation translation function became deeply embedded in the bloodstream of people who would become excited about and pursue this work.

Adam Mossoff: Americans have been very practically oriented and focused on real-world problem-solving from the beginning, in addition to having norms of individualism and respect for property rights. Alexis de Tocqueville first noted this in his book Democracy in America. Tocqueville, a European aristocrat, conducted what we would now call a fact-finding mission because Europe was befuddled by America’s success.

As we’ve seen in “Hamilton,” particularly in the song “You’ll Be Back,” they really did think we were just an upstart, like teenagers — a know-it-all little new country. They believed we would eventually come begging to be readmitted into the English Commonwealth. Yet 60 years after our revolution, we were amazing the world at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition (the first world’s fair), with innovations like rubber, the sewing machine, the telegraph, the mechanized reaper, and many other inventions.

Tocqueville kept noting how pragmatic and practically oriented Americans were. Everyone thought about practical applications in their own lives — what they could do to make their lives better and make everyone else better off as well. Our patent system and property rights served what Dr. Zorina Khan, an economist who studied the history of patent systems and innovation, called “the democratization of invention."

Redefining patents from privilege grants from the crown into property rights made them accessible to everyone. This aligned with our culture’s practical orientation and individualism. The industrial revolution shifted from England to the United States in the 19th century. The pharmaceutical revolution began in Germany but moved to the United States by the early 20th century, partly because our patent system offered protections for deploying products in the marketplace. By the mid-20th century, technological and scientific revolutions were happening primarily in the United States, intimately connected with the patent system — the computer revolution, the internet revolution, the biotech revolution, and now the mobile revolution.

Modern Patent Pitfalls

Jordan Schneider: Let’s jump to the 21st century. What are the key developments in patent policy we’ve seen in the United States?

Adam Mossoff: Looking back to about 2005-2006, the United States has shifted from providing effective and reliable protections for patent rights to destabilizing them as property rights. It became much harder to obtain and keep patents, as they could be easily invalidated or canceled by an administrative agency at the patent office called PTAB (Patent Trial and Appeal Board), which had cancellation rates of 80-85%. One program even reached 100% at one point.

It became very difficult to stop infringers from stealing inventions and patents. Injunctions are no longer available, and damages have been reduced significantly. A narrative pushed by companies and other interested parties claims patents obstruct innovation and undermine the innovation economy. This created what amounts to a moral panic about the patent system in Washington, D.C. — a radical change from how the United States previously operated.

Jordan Schneider: Can you give the steel man case in favor of the new paradigm you just laid out?

Adam Mossoff: The steel man arguments for these changes to the patent system are that today’s technology differs from before. Things move faster, it’s more complicated, and people have more reasons to invent new technologies beyond patent system motivations. Patents might be needed for some limited innovations, like drugs, which require years of investment. However, for most products and services, the internet makes it possible to become famous and sell products. First-mover advantage and other justifications for marketplace success exist now. Patents can obstruct people by allowing others to stop these activities.

Jordan Schneider: This seems like a good place to bring in Elon, perhaps the only person who can tweet something about patents and get 100,000 likes. Tesla and SpaceX are famously patent-shy and patented basically nothing. A few weeks ago, he tweeted that only patents for things that are super expensive to prove work, but are then easy to manufacture — like stage three drug trials — have any merit. What’s your take on that?

Adam Mossoff: Elon has been a longtime patent skeptic, previously tweeting that we don’t even need a patent system at all. This recent tweet actually shows improvement — he’s softened his opposition to patents. Years ago, he announced Tesla was giving away all its patents in a blog post titled “All Our Patents Belong to You” — a play on the meme, “All your base are belong to us."

However, it’s not true that Tesla doesn’t have patents! Tesla has numerous patents on their cars’ designs and revolutionary battery technology. That announcement from 15 years ago about anyone using their patents wasn’t entirely accurate. The Tesla policy was actually a cross-licensing proposal — if you use any of our patents, we get access to all of yours.

They wanted people to build cars because they had key battery technology for all electric vehicles. They wanted people buying their batteries since they had the manufacturing capability. They were exercising their patent rights by choosing who could access their patents as property owners.

His recent statement about only needing patents for high upfront cost innovations that are easy to copy shows a misunderstanding of patents. People think of patents as the original English Crown Privilege monopoly grant — incentivizing initial invention investments with a monopoly promise. While that’s one function of patents as property rights, they do much more: facilitating commercialization, deployment, and licensing.

Even in the biopharmaceutical sector, where people view drug manufacturers as big monopolies, there are massive cross-licensing deals and information sharing agreements over patented technologies. This enabled the pharmaceutical sector’s revolutionary response to the COVID pandemic through existing licensing deals and manufacturing agreements, allowing quick vaccine production and distribution. Patents, like all property rights, facilitate commercialization of new technologies.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about the Trump strain of thinking. What else is in the Trump world soup when it comes to ideas around the future of patent policy?

Adam Mossoff: Trump himself relies on intellectual property trademarks, putting his name on everything — hotels, steaks, wine, everything. While he doesn’t rely on patents as much, he does use trademarks, which is a type of intellectual property. People typically think of patents when discussing intellectual property, but there’s a broader range of different types.

In his first administration, Trump was very supportive of reliable and effective patent rights through his administrative officials. Andrei Iancu, the director of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in the first Trump administration, understood the importance of reliable and effective patent rights and has been an advocate for them since 2020.

Trump could potentially return to that approach, emphasizing reliable and effective patent rights by changing course and reinstituting certain protections that patent owners once had. However, because Musk has Trump’s ear, and there’s a populist strain of thought in the Trump world — populism tends to view patents as monopoly grants — there’s concern it could go the other way. He could end up repeating some of the attacks we’ve seen in the past 10-15 years and under the Biden administration on patents in both the technology and biopharmaceutical spaces.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about the global dynamics. How about we start with your one-on-one on China’s recent approach to intellectual property?

Adam Mossoff: People hear two main themes about China.

They steal our intellectual property. In fact, during the first Trump administration, this was partly the basis for starting his trade war — he alleged, rightly so, that China was engaging in billions of dollars of theft. The FBI director testified to Congress that it’s one of the largest wealth transfers in human history, with Chinese government and entities stealing intellectual property assets estimated at hundreds of billions of dollars.

China is incredibly innovative and has developed their own very strong patent system.

Well, which is it? Are they stealing intellectual property because they’re not innovative and don’t respect intellectual property rights, or are they protecting intellectual property because they’re incredibly innovative themselves?

The answer is both. The Chinese Communist Party has adopted both policies as part of a geopolitical strategy and domestic industrial policy growth strategy. They want to grow their economy and become a superpower through two methods — promoting their own citizens to become innovators and inventors while fostering economic growth internally through a strong patent system, and stealing technologies they don’t have from other countries. This integrated approach is unique historically, which explains why many find it confusing.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s bring it back to the 18th century. The incentives that both the UK had in trying to get inventors and industrialists from Europe to bring their inventions, as well as what the U.S. did to lure manufacturers or engineers over from the old world, are really interesting. How are some of those practices being replicated today?

Adam Mossoff: Some people say China’s just doing what the United States did, claiming the U.S. lured British inventors and others to get access to technology. One often cited example is industrial espionage in the 1790s by an American citizen of loom mechanics for making shirts.

These people point out that England also used their patent system as monopoly grants to lure people away from Italy and the continent to England, which was true. Patents were originally royal monopoly grants offered to promote industrial economic development in England during the 16th and 17th centuries by attracting inventors from Italy and the continent to establish their manufacturing and arts.

While it sounds like China is just following England’s and America’s historical precedent, the United States never officially did what England and China did. The U.S. did not have an official policy of intellectual property theft — you will search in vain for this in law or regulations. Individual cases of industrial espionage occurred but did not reflect U.S. government policy.

The United States was one of the first countries to recognize that foreign inventors had equal rights to obtain patents under U.S. law as American inventors. The U.S. took seriously the idea that these are property rights, regardless of whether you came from England or invented in France. You could get a patent in the United States under the same terms and protections as U.S. inventors.

This question highlights common confusion. Claims that this is how the United States developed itself are incorrect. While individuals may have engaged in industrial espionage throughout human history, the integrated policy of using patents as an economic and domestic industrial development device — what England did, and what China does now — differs from U.S. practice over the past 220 years.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss standard essential patents and the fight over licensing. You can’t credibly just steal your way into that, but China and the EU have been trying to pull levers in recent years to impact how those negotiations play out. How have those two bodies tried to get their way on these issues?

Adam Mossoff: Almost all technologies being deployed and driving the mobile revolution — standard essential patents covering 4G, 5G, WiFi, and other technologies underlying our computer devices — were invented primarily in the West. Mobile communications technologies were developed by Qualcomm, InterDigital, Nokia, and Ericsson.

Jordan Schneider: Huawei too — they’re getting a big chunk of the next generation.

Adam Mossoff: They’re contributing now, but Huawei didn’t invent these technologies in the 1990s. The foundation of the mobile revolution comes from Western companies. While Huawei is now classified as one of the five leading contributors to 6G and somewhat to 5G, when you control for patents valuable to standard development organizations rather than just filed and declared patents, most still come from Western innovators.

I recently published a white paper at the Hudson Institute showing that almost all royalty flows on mobile technologies go from Asia to the United States and Europe, not the other way around. China’s interest remains primarily from the implementers’ perspective — Huawei’s handsets, Xiaomi, HTC, and others. Their interest is in depressing royalty rates because that’s a cost to their companies.

I use “companies” loosely because while Huawei, HTC, and Xiaomi look and act like companies, they differ from IBM, Qualcomm, or Apple. China is a communist country — if Xi calls up Huawei and tells them to do x, Huawei does x. If they don’t do it, someone gets disappeared.

They use China’s court system to advance the CCP’s domestic policy agenda, protecting their companies and making them better off relative to Western competitors. They’re using court processes to artificially depress royalty rates worldwide.

Jordan Schneider: I hear you, but it’s normal for governments to want their companies to flourish and succeed relative to companies they might be paying for licensing abroad, right? Given that, what are the specific legal strategies that the Chinese and Europeans are pushing? How has the U.S. Government responded to those arguments?

Adam Mossoff: I would challenge the normative implication of your premise. While any country can do what China is doing as a descriptive matter, the question is whether they should. The United States doesn’t treat plaintiffs from England, France, or China differently than plaintiffs from the United States in its court system. That’s called rule of law, which ensures equal treatment of people regardless of national identity or citizenship.

The rule of law is a key feature that made patent systems function successfully in the United States and the West. You can’t have successful markets and societies without it. It’s a foundational violation of the rule of law to pretend to give foreign plaintiffs a valid court hearing while actually operating as an tool of Communist Party interests. We don’t do that — if Chinese citizens have rights violated in the United States, we don’t restrict their ability to file lawsuits or give them different types of damages than American citizens.

Jordan Schneider: What’s the pitch to your median Chinese government official? How would you explain to them this view of patents would actually benefit China, its companies, and its future growth trajectory?

Adam Mossoff: Merely having a patent system doesn’t guarantee innovation and growth. Economists and historians widely recognize patents as key elements to successful innovation economies and societal economic growth — but they’re not the only factor. Patent systems must exist within a country governed by the rule of law, with stable political and legal institutions that function properly as legal institutions distinct from political institutions.

This made the United States patent system succeed. We broke from England and started defining patents not as arbitrary crown grants limited to aristocrats, but as rights accessible to anyone meeting legal requirements. Patents were enforceable in court regardless of economic status, national background, heritage, or sex — women could get patents just as readily as men. It was truly a rule-of-law system governed by stable institutions.

China must recognize they can’t just build a patent system and declare success. If they’re manipulating it through political policies like domestic industrial policy and treating foreign patent owners differently from domestic ones, they’re undermining the very reasons for having a patent system and a successful country.

Jordan Schneider: What leverage does the U.S. Government have in influencing how these legal proceedings and commercial negotiations play out in both EU and Chinese contexts?

Adam Mossoff: The U.S. Government can take two approaches.

First, domestically, we need to reestablish reliable and effective patent rights. Patents should be property rights backed by presumptions of injunctions for infringements, which drove the innovation economy for 200 years.

China and other countries quote our own policies when we complain, noting we’re doing similar things to our patent owners.

We’ve abdicated our gold standard patent system and need to reclaim that moral, legal, and economic high ground.

Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, the Wright brothers — these innovators succeeded because of our patent protections. Restoring these protections will drive people to file lawsuits in the United States again, licensing activity will occur here, and we’ll regain leadership through our system of law and rule of law governing our courts and institutions.

The international realm presents more difficulties because you can’t force another country to comply if they resist. China can refuse our demands, which Trump addressed in his first administration through the trade war and sanctions. While I don’t personally support sanctions and trade wars as they’re economically self-destructive long-term, intellectual property theft is also destructive. We have limited tools internationally to force respect for our citizens’ rights, including economic and political isolation as leverage points.

Most importantly, we should focus on what we control and what our government is responsible for — protecting U.S. innovators’ rights domestically, ensuring maximum protection, and reestablishing our leadership both legally and economically.

Outtro Music

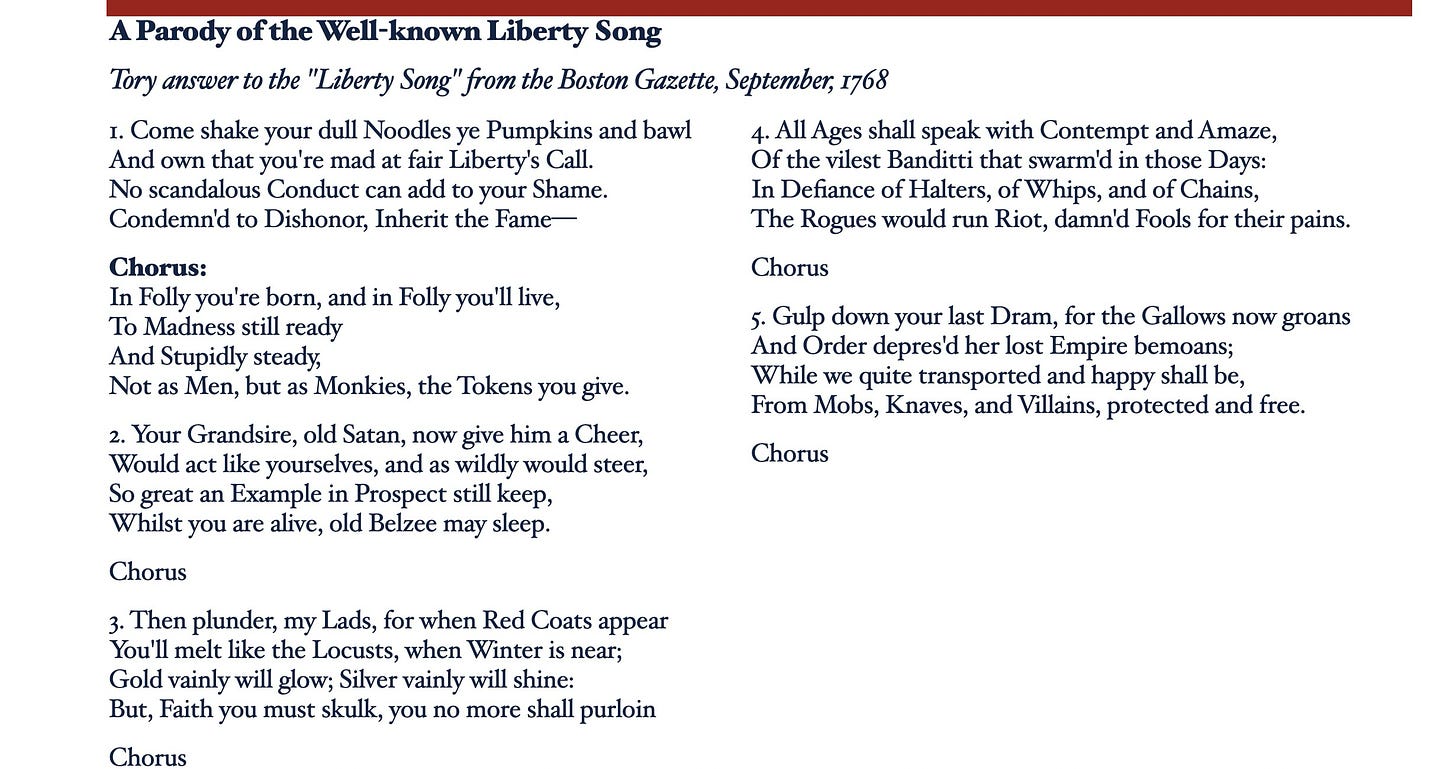

And the hysterical Tory retort!

Good episode but need to correct the record regarding the “all our patents belong to you” phrase Elon used. It is a video game meme from the early 1990’s not from the Iraq war. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_your_base_are_belong_to_us