Matt Pottinger reported for years out of China, served as a US Marine Corps intelligence officer in Iraq and Afghanistan, and held several senior roles on the NSC staff, concluding his time as the Deputy National Security Advisor for the Trump White House.

Today, Matt chairs the China Program at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies.

In this interview, we discuss:

How Matt expects a second Trump administration’s China policy might develop.

Why Trump is leaning more into strategic ambiguity than Biden, what that means for deterrence, and how that impacts the likelihood of him standing by were the PRC to invade Taiwan.

What China’s slowing growth means for domestic governance and international relations

Why bipartisan support for the US-China trade war will continue to shape the contours of great-power conflict.

Matt’s look at the origins and political fallout of COVID-19.

Plus, reflections on Mike Flynn and how Trump ran his NSC.

But before we get to the interview … be sure to spread the word. ChinaTalk is looking to hire an analyst to cover China and AI! Consider applying here.

If you’re in New York, drop by tomorrow to ChinaTalk’s meetup with Asianometry at Pier 57.

Reading Between the Lines

Jordan Schneider: So Matt, one of the things I really respect about you is you’re really in the trenches, reading through speeches and encouraging people to take them seriously. I’m curious if you think Americans should do the same for Trump when he talks about flirting with the idea of a dictatorship?

Matt Pottinger: Look, I think you should always read a leader — whether it’s President Trump, or it’s Xi Jinping, or it’s President Biden — and I think what leaders say extemporaneously, and what they say in carefully crafted speeches, both matter. And it’s important to weigh them in the context in which they’re delivered.

Sometimes if it’s a 3:00 a.m. tweet, you can understand that it’s probably impulsive, but also an honest expression of an impulse at that moment.

But at the same time, the 3:00 a.m. tweet doesn’t always translate into hard policy the way that crafted speeches are. Speeches delivered at the State of the Union or what have you are usually pretty good expressions of where the strategy is headed for an administration.

With Xi Jinping, the thing that I think we’ve tended to do a bit too much of is to project onto him what we think he’s going to do, by looking at signals that are actually not coming out of his mouth, or they’re coming out of his mouth in a context where we should be more skeptical.

For example, if he’s speaking to a crowd at Davos to a bunch of Western business leaders — or for that matter, if he’s speaking in San Francisco at a high-paid dinner function on the sidelines of the APEC forum like last November — we should be a bit more skeptical of the message that he’s delivering there, because we know it’s meant for our ears.

But in a Leninist system, when the leader is speaking to his own bureaucracy — I think we should be giving far greater weight to those speeches. Those speeches tend to get ignored, usually because they’re often kept secret for a number of weeks — or months or years — after they’re delivered. Sometimes we can find them only in Chinese-language publications. They intentionally refrain from translating into English those speeches or statements by Xi, or only portions of them get translated, and sometimes the translations are selective or even manipulative. They tend to make things sound a little bit softer in the English than in the Chinese.

So yeah, it doesn’t matter if you’re talking about President Trump or Xi Jinping: people would be wise to try to listen to primary-source statements. Primary sources are more important than things that are filtered through media.

ISAF & General Mike Flynn

Jordan Schneider: So speaking of primary sources, I want to take it back to your CNAS article with Michael Flynn, which actually got me to apply for an internship at the DIA back in 2011, I think.

Matt Pottinger: Did you do it?

Jordan Schneider: They didn’t take me!

Matt Pottinger: Their loss.

Jordan Schneider: The “I want to be a journalist for the intelligence agency” hadn’t filtered up to their college intern recruiting process at that point. Matt, reflections on that document fifteen years later?

Matt Pottinger: Well, I haven’t read it for a long time — but it was a labor of love. I had just finished a deployment at the battalion level down in Helmand Province, and had the advantage of having been able to cover a lot of ground in that job. I was working as the S2, I was the intelligence officer for a logistics battalion — but I spent a lot of my time with British forces and with a Marine rifle battalion, spread out across a pretty large area. We had poppy fields all over the place, growing opium — the Taliban were extracting taxes from those opium growers. I caught a surprisingly broad glimpse for a lieutenant of this counterinsurgency that we were trying to wage, which wasn’t going terribly well when I was there from 2008 to 2009.

So in mid-2009, I was very quickly deployed again to work for Mike Flynn, who was working as the J2. He was the senior intel officer working for General Stanley McChrystal, the ISAF commander, the commander for US forces and Allied forces in Afghanistan — a great leader. And I was allowed to be their focused telescope, in a sense. I covered ground all over the battlefield, every region where we were fighting, interviewing most of our allies — dozens of allies — talking to Afghan troops, and aid workers, and humanitarian groups, and the rest.

And that report was a synthesis of what we — my co-authors and I, Paul Batchelor, General Flynn, and I — believed were things that we weren’t getting right. And of course, I was trained from the Basic School in the Marine Corps that you don’t send a memo complaining about what’s going wrong without trying to actually offer remedies.

So a heavy part of that report — I don’t know, it was a 10,000-word report — consisted of suggested remedies. Many of these got adopted, some didn’t, and many I tried to implement during the second half of that second deployment when I was in Afghanistan.

Jordan Schneider: Matt, do you have a theory of what happened to Michael Flynn, or maybe more broadly, why Americans in recent years have gotten more entranced by dark explanations of what they see in the news?

Matt Pottinger: Well, look, I have real affection for Mike Flynn as someone that I fought alongside and who was my commander there. I worked for him briefly on the NSC staff. I think there are probably a lot of areas where I would disagree with him today on certain things, but I think he played a really important role in these wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He was iconoclastic in ways. He was someone who didn’t really care about promotion — he was someone who really wanted to win.

You find that, sometimes, wartime generals are a very different breed from successful peacetime generals — and I think Mike Flynn is a quintessential wartime general. He’s someone who’s willing to try to take significant risks, to dump orthodoxies, to try to experiment with new things, to get things done. He played a major role over those years that we were fighting really tough wars in those two countries.

The Long Wake of January 6

Jordan Schneider: Coming back to Trump — in your testimony, you said that “our national security was harmed in a different way by January 6, and that it has emboldened our enemies by giving them ammunition to feed a narrative that our system of government doesn’t work, and that the United States is in decline.”

I’m curious to hear your reflections on what another Trump administration would do both to that narrative, as well as the broader correlation of American national power.

Matt Pottinger:

January 6 was a disaster, right? That statement that you just repeated from me, I still believe.

I’m not going to try to guess what a second term for President Trump exactly would look like. Americans have available all the information that I have available to myself. I think people will make a decision. I’m not going to try to front-run this election by trying to predict how it’s going to turn out or what the consequences of that election will be. But we are a democracy. If President Trump is elected, that means he has a mandate — just as I think President Biden today has a mandate, because he was elected in 2020.

Jordan Schneider: I feel as though you have a few more data points, at least from the perspective of US-China relations. Can we do a branching scenario analysis of what four more years of Trump and Xi could potentially look like? How are you thinking about the different tracks that we could potentially get on?

Matt Pottinger: One of the interesting things is that there are many aspects of President Biden’s policy that were continued from the Trump years.

I think President Biden’s policy is closer to President Trump’s policy on China than it is to President Obama’s policy, when President Biden was the vice president.

That’s interesting. That tells me that we must have gotten some things right, and some things that are now viewed as a consensus — we have the benefit of bipartisan consensus.

Trump’s Trade War, Then and Now

Matt Pottinger:

I think that if President Trump comes back in, he’s going to focus on trade. That’s my instinct, just from knowing him and following some of his public comments during his campaign.

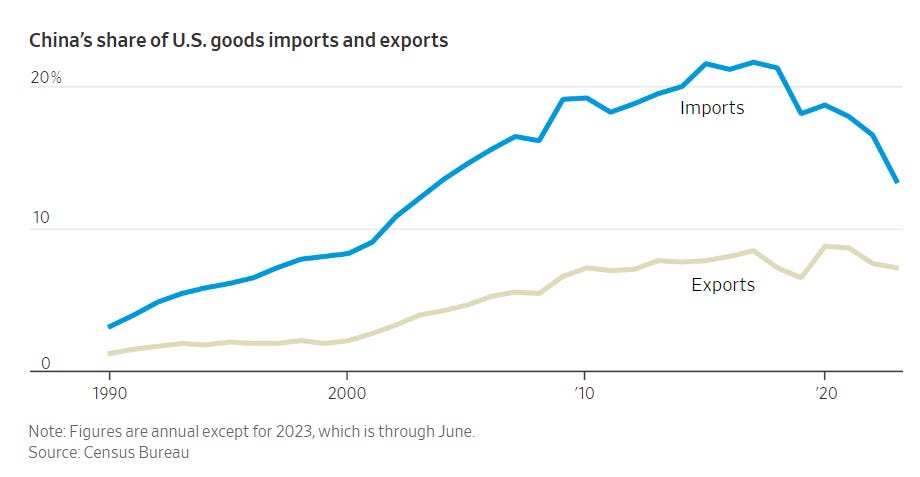

I think that the 2018 tariffs that he put in place — and remember, if you go back and remember why those tariffs were put in place, it was an investigation under what’s called Section 301 of our 1970s trade law. Bob Lighthizer, the US Trade Representative working for President Trump, did a thorough investigation of Chinese theft of American intellectual property and proposed tariffs as a remedy after he completed those six-plus months of investigation.

President Trump accepted the recommendation to impose tariffs. Originally it was only tariffs on about $35 billion worth of Chinese trade. It sounds like a big number, but it’s actually a small portion of what China exports to us. If China had not retaliated, we might have been at $35 or $50 billion worth of exports getting tariffed, as opposed to hundreds of billions of dollars getting tariffed.

But China thought that it could — and I think they misread President Trump. They thought that they could kind of bully Trump by mobilizing the American business lobby to undermine him, to mobilize the farm lobby to mobilize against him.

And all of that backfired for China: we ended up in this escalating tariff war, and those tariffs are still in place today.

If President Trump comes back, for one thing, I wouldn’t be surprised if he completes the investigation that Katherine Tai — President Biden’s US Trade Representative — inaugurated but never completed. And that was a Section 301 investigation into illegal or unfair Chinese subsidies and the harm that America’s economy has suffered as a result of these subsidies. I wouldn’t be surprised if that baton gets picked up where it was dropped.

By the way, I doubt it was Katherine Tai who dropped that baton. I think it was more of a battle between the Treasury Department and the US Trade Representative, and the stalemate was that we would keep the Trump-era tariffs, which are still in place, but would not proceed with a second investigation into abusive trade practices by China.

I think President Trump will probably pick up that baton and run with it. That will be the most obvious area where I think you’ll see a significant shift.

Jordan Schneider: Josh Rogan’s Chaos Under Heaven had a pretty evocative portrayal of the Biden competing camps. Trump also had competing camps when it came to thinking about how to engage with China. Reflecting back, do you have a heuristic on how those decisions ended up resolving themselves?

Matt Pottinger: It’s funny. On trade, President Trump came into office with views of China heavily animated by his sense that we had been taken advantage of for decades, which of course we have been.

But on some of those thornier issues that played out over time, I think that Xi Jinping, in many ways, drove US policy into a tougher mode in response to some of the really egregious steps that China had been taking under Xi Jinping.

Just for a couple of examples: think about what happened in Hong Kong. You have a treaty between the United Kingdom and China — registered at the UN, the Sino-British Joint Declaration — that guaranteed that Hong Kong, upon being handed back to China from the British in 1997, would enjoy fifty years of a high degree of autonomy. That was prematurely stilettoed in the heart less than halfway to that fifty-year mark. China undermined the Basic Law, undermined the rule of law, undermined free speech, and undermined the high degree of autonomy that they had promised Hong Kong.

You look at how China handled COVID, right? I mean, you’ve seen probably some of the more recent reporting just on things like how much China knew in December 2019, and yet it was providing flagrantly false information to the World Health Organization about this virus that was circulating and how dangerous it would be — lobbying countries to keep their international flights open, even as China canceled domestic travel from Wuhan.

I would say President Trump became pretty fed up with things that were not only related to trade, but that went far beyond trade.

Prospects for US-China Dialogue

Jordan Schneider: So Matt, what types of US-China dialogue make sense? And what is the right posture for an American president to take when engaging directly with Xi’s China?

Matt Pottinger:

The first thing is, you want high-level engagement. And when I say “high-level,” you really want top-level engagement.

You want President Biden to be talking to Xi Jinping on a reasonably frequent basis. He is doing that. He’s made an effort to try to keep a dialogue going. They’ve met twice in person, and they’ve had a number of phone calls or video calls.

President Trump — the same thing. I can’t remember how many times he and Xi Jinping met — it was maybe five or six times, plus a significant number of phone calls. That is good. Again, you’re dealing with a Marxist-Leninist system where there’s one guy who makes all the important decisions. You want to have access to that guy.

The only way that you can really know things important to the United States are being communicated to the top is if the President is talking to his counterpart, Xi Jinping.

And by the way, I don’t think that a lot of things that are communicated below that level are making it back to Xi Jinping. I suspect that the Biden administration, or some officials, would agree with that statement. That was the conclusion we drew during the Trump years. So high-level, top-level communication is actually really important, and I support it, whether it’s President Trump or President Biden.

What is a lot less helpful are these mid-level dialogues. We’ve had a lot of them over the last quarter of a century. You’ve had the JCCT (that was led by the Commerce Department), the US-China Security and Economic Dialogue — it’s almost as if people are just taking words, randomly mixing them together, and christening these new dialogues. Those dialogues have not served US interests well at all over the years.

The more we spoke at a working level with China, the worse the theft of American intellectual property, the worse the trade deficit. Take your measure, things only got worse and worse over time. And yet we built a larger bureaucracy that was dedicated to engaging at that level. And so it really became a tool for China to string us along — tap us along, as some would say.

But I do think that there are things that we ought to have a common interest in. But at the same time, if we have a common interest — whether it’s dealing with climate change, or dealing with terrorism, or proliferation risk, or for that matter, a future pandemic — if Xi Jinping and the Communist Party really believe that those things are in China’s interest, then they will do them anyway, or they’ll even seek us out for engagement on those things.

But the idea that we’re not trying hard enough — that we’re not setting enough nice mood music, or we’re not appeasing China sufficiently to draw them into a constructive dialogue — is the wrong kind of thinking. It’s just not the way it works, and sometimes it’s counterproductive.

I’ve talked in the past about how I made attempts to open dialogues on some of those topics I just mentioned with China — and it became clear to us that the CCP viewed those things as leverage. In other words, if we expressed our concern about the proliferation of nuclear weapons, or even about the risk of a future pandemic, China would try to extract other, wholly unrelated concessions from the United States, as the price of admission for having conversations with them about things that are ostensibly in our common interest.

So that again goes to the nature of that system. We’re not dealing with a fellow democracy here, where there’s a baseline of trust that people are working for the good of their people. Leninist systems don’t work for the good of their people. They work for whichever party — the Communist Party — wants to maintain power, and that is always the first and last thing that they’re thinking of.

Trump and the US Commitment to Taiwan

Jordan Schneider: Coming back to taking leaders’ words seriously — we’ve had some uncomfortable comments out of the Trump campaign with respect to Taiwan. Matt, I’m curious for your reflections on your time in the White House on how issues around Taiwan played out.

Matt Pottinger: Over the course of his administration, I would say President Trump became more focused on what a disaster it would be for the United States — both in terms of our prosperity and in terms of our national security — if Taiwan were to be coercively annexed. I do think that his understanding and focus on that increased over those years.

When President Trump has spoken publicly, in office and out of office, he has tended to revert to what I would call this idea of strategic ambiguity, which has really been US policy for forty years. He said that he’s not going to telegraph in advance exactly what he would do. That’s more or less in keeping with policy up until President Biden. President Biden has gone farther. President Biden has said four times now — quite clearly, quite deliberately — that he would commit US forces to defend Taiwan if Taiwan were attacked. You could say that it was an off-the-cuff remark the first or second time, but he said it four times.

So I think that constitutes a graduation from strategic ambiguity, irrespective of how spokesmen tried to spin it in that administration. The president has spoken, and according to the Constitution, the president is the one with the authority to speak on those matters.

Jordan Schneider: So what’s your personal take, Matt? Should strategic ambiguity be in the dustbin of history, or is there still value to the concept?

Matt Pottinger: I guess I’d say I don’t think any president or any candidate for the presidency should back away from President Biden’s stance. You don’t want to draw a red line unless you mean to back it.

But I think that the stakes are so high, that if Taiwan were to be invaded, it would make what’s happening in the Middle East and in Ukraine right now look like child’s play by comparison.

I think the effects would be quite dramatic for employment, prosperity, and security for the United States. I don’t think we should back away from the rhetoric that President Biden has delivered.

Stalling GDP Growth in the PRC

Jordan Schneider: Matt, what’s your take on how Beijing is likely to — and how American leadership should — price in a future in which China is growing a lot slower than people maybe would have expected five years ago?

Matt Pottinger: Slower growth is a new normal for China. Even if Xi Jinping moves to try to stimulate parts of the economy that have really gone dormant — like the real estate sector — it’s not going to be anything like the dynamic economy that it was before the Xi Jinping era. And I expect it to continue to grind slower.

I’m very skeptical that the Chinese economy grew the 5.2% (or whatever it was) in 2022. And the markets would agree with me, judging from what’s happening with foreign money right now. It’s exiting China. You’re seeing a net outflow of both passive stock-market investment and also foreign direct investment. That will hamper the long-term aspirations of Xi Jinping — but I don’t think it will do anything to hamper his near to medium-term aspirations. And that’s why we’re living in a very dangerous decade right now, in my view.

How to Win Friends and Influence Bureaucrats

Jordan Schneider: Usually when NSC staffers end up in books, it’s not in a particularly positive light — but you’ve had so many nice things written about you! Is there like a secret you can tell everyone, all the PR folks or people living in the bureaucracy?

Matt Pottinger: I’ve had my share of pretty nasty things written as well! I haven’t weighed the negative to the positive. But I don’t know.

I believe that it’s good for people to want to serve in those jobs. I’m very proud of my service on the NSC staff. I’m proud of what we got done. I am proud of my colleagues that I worked with. I worked very hard to try to maintain a good working relationship with a pretty broad range of people.

I remember someone once told me that you should try to have a short memory when you work in those jobs. What I took that to mean — and what I tried to put into practice — was, when I was occasionally double-crossed or simply lost honest arguments, I didn’t hold grudges against colleagues in other departments and agencies. I tried to continue working with them, and tried to have a short memory about those things. It just allows you to get more things done.

Jordan Schneider: Last one for you, Matt. We haven’t really had a generational wake-up call, like a Kennedy inaugural or a 9/11, to get people motivated to work on China competition-adjacent issues. I’m curious maybe for your pitch, as well as what you think could be a trigger on the horizon — that’s short of World War III — where you get a kind of generational groundswell of interest in the topics that you and I think about all day.

Matt Pottinger: I would have hoped that COVID would have been enough of a wake-up call, but we ended up just tearing each other apart during COVID rather than coalescing to a sense of national purpose. I’m waiting for that moment for us to coalesce.

I think there are promising steps, given that there’s been continuity in the China policy — or at least significant strands of continuity, from Trump to Biden, and I hope that continues in a second Trump or a second Biden administration. But I think that we have to do a better job of recognizing how many of our red lines — or what should have been red lines — have been crossed.

Those red lines could include the theft of our intellectual property, or China’s conniving on the fentanyl trade — which not only kills 100,000 Americans a year, but leaves whole communities destroyed, the people who don’t die but are hooked on this stuff. Just the bad faith in which China managed the COVID crisis — they viewed it as an opportunity to acquire greater leverage over democracies, by withholding important drugs, hypodermic needles, or personal protective equipment.

I’m waiting for that moment where people are so fed up with this that we start to press a little bit more aggressively our interests. I think that that would actually be stabilizing, by the way. I’ve said that one of the paradoxes of a Marxist-Leninist system is that the more comfortable it is, the more aggressive it becomes. You don’t want Beijing to feel that they’re able to be the protagonist in this story, calling all the shots. Supporting the largest war in Europe since World War II — are you kidding me? They’re the main propaganda, diplomatic, and material supporter for that war. They’re the major propaganda, diplomatic, and material supporter of the Iranian regime, which just blew up a platoon of American soldiers and killed three of them. This is outrageous stuff, and Beijing is on the wrong side of a lot of these things.

So I’m still waiting for that moment. I think it will come, but I hope it doesn’t take a tragedy on the order of some of the things we saw in the twentieth century for us to get there.

COVID-19: A Policy Post-Mortem

Jordan Schneider: Matt, since you brought it up, what was it about the timeline that ended up playing out with COVID, where it led us into the politicized trajectory that it ended up being? How do you divide the blame on that from all the different players? What could have gone better?

Matt Pottinger: I think that our public health bureaucracy is not geared, still to this day, to handle a fast-moving, dangerous pandemic. We’ve got big work to do. I don’t think that’s been fixed under the Biden administration. We’ve got real problems with the public health bureaucracy, number one.

Number two: the world is engaging in incredibly dangerous research — this so-called “gain of function” research, where viruses are given the attributes that would make them more infectious to human beings. “The juice is not worth the squeeze,” as we used to say in the Marine Corps. That’s not to say that there shouldn’t be any gain of function research, but it should be high-reward, low-risk, gain of function research used on animal models, and not on human-type tissues.

We’ve done nothing to lower the danger. Someday, if we discover that this was a naturally occurring virus — although I think the default is very clearly that it was an inadvertent laboratory accident — there’s more and more circumstantial evidence falling on that side of the ledger. But even if it was natural, why wouldn’t we be taking steps to try to mitigate against both sources of a dangerous disease? That is, to stop doing really dangerous scientific research, and also to try to keep people away from wildlife, in ways that could promote a natural spillover, zoonotic-origin pandemic.

Jordan Schneider: I guess the big puzzle for me is, we have Republicans voting down those bills that would have put more funding into nasal sprays, as well as this future-looking analysis of wastewater, and all that good stuff that would help us set us up for the next one.

Matt Pottinger: Look, I’m a big believer that we should be building surveillance for these things. The technology has gotten to a point where you can surveil nature, without having to go grab bats, swab them, and bring them into urban centers. I’m not talking about that. I’m talking about passive testing, as you mentioned, of wastewater and things in the environment that would tell you trigger anomalies. It’s testing wastewater on airplanes and so forth. I think we need to be doing a lot more robust work in that area.

In the second part of this interview, we discuss:

How the two NSC models of “regular-order” and “maverick” shape US foreign policy

Why Pottinger thinks long hours and burnout might just be par for the course when it comes to great power competition

The critical need for bureaucratic trust if a president wants to devolve decision-making