Powering China’s Data Centers: Batteries or Nukes?

Does a Great Wall of Batteries make any sense?

Caleb Harding is a senior studying CS and Chinese at BYU. He previously interned at the US Embassy in Jakarta and Doublethink Lab in Taiwan. This summer, he and ChinaTalk’s resident mathematician Lily Ottinger ran the numbers on China’s power production. Here’s what they discovered.

AI development is facing an imminent electricity bottleneck. Data centers collectively make up 3% of total US electricity demand, and some predictions indicate they could consume up to 8% of electricity demand by 2030.1 And already, energy-consumption concerns have stalled some US data-center construction.

This leaves companies in a tough spot: if they can’t get enough energy to train their models, they will fall behind.

In response, some companies have quietly walked back promises of carbon neutrality, pivoting away from renewables and burning fossil fuels to pick up the slack. Meanwhile, Amazon has purchased a data center right next to a nuclear power plant to ensure an adequate supply of green energy.

China is staring down the same bottleneck. Today, we’re exploring China’s plan to unlock green energy abundance on the journey to become a world leader in AI.

Your firm should be sponsoring this post! Respond to this email, and I’ll send over a media deck — we’d love to explore how to partner.

China’s Plan: Eastern Data, Western Compute

Back in 2020, China started a national initiative to deal with the energy demands of computing.2

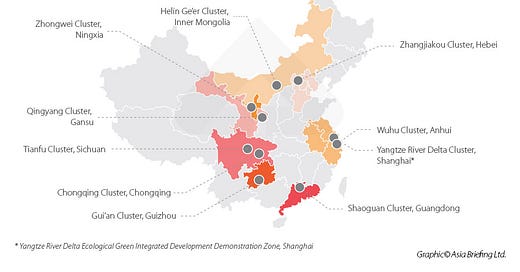

The plan, called “East Data, West Compute” (EDWC) 东数西算, aims to build out a network of eight computing hubs in western China and ten data clusters in eastern China. Western computing hubs draw on the region’s plentiful renewable resources to store and process less frequent-access data, while eastern computing hubs are free to focus on data with high network requirements.

EDWC has been hailed as the solution to the energy bottleneck. The plan has two key goals: make data centers green and make them efficient.

Let’s see if either goal is realistic.

Make It Green

Chinese data centers used 130 billion kWh of electricity in 2022, and they are expected to use 380 billion kWh per year by 2030. To avoid breaking the carbon budget, the Chinese government’s set policy goal is to power new data centers with 80% green energy by 2025.

That’s a gargantuan shift from the status quo — 70% of the electricity currently consumed by China’s data centers is supplied by coal. Non-fossil-fuel energy sources are reportedly still prone to outages. From Huawei’s Data Center report:

Still, the utilization of green energy is unpredictable and cannot provide a long-term stable power supply, which may lead to fluctuations or even collapses in the power system. (pg. 43)

然而,绿色能源的利用具有不可预测性,不能长时间持续稳定的供电,可能会导致电力系统的波动甚至崩溃。

The problem: solar and wind are intermittent.

Thus far, the strategy for powering data centers with renewables has been two-pronged:

Expand the overall build-out of green energy in the grid generally, thereby indirectly raising the proportion of green energy used by data centers.

Directly wire renewable-energy capacity into the power systems of the data centers, so that computation can draw from renewable generation when the power is available. A pilot project in Horinger New District, Inner Mongolia, for instance, has achieved a green electricity substitution rate of 43% by using this method.

Even so, neither of these strategies can conquer the intermittency problem. The guaranteed source of fallback power is still the broader coal-dominated energy grid.

So how can intermittency be defeated? Huawei’s 2023 report boldly proclaims that data centers will be 100% green-energy-powered by 2030. The report champions wind energy as the best solution, pointing to a data center Huawei built in the ultra-windy Inner Mongolian city of Ulanqab in 2013.

“In the future, wind power, photovoltaic power, hydropower, and other renewable energy sources will become a universally available means of energy supply.”

风电、光伏、水电等可再生能源将成为普遍的供能方式。

~Huawei’s 2022 “Green Energy Development 2030” (绿色发展2030) report.

The Huawei report is far less optimistic about the potential of solar energy, which is currently limited to powering auxiliary systems in data centers, such as lights, elevators, and the coffee machine in the break room.

The authors are quick to clarify, however, that more storage capacity — ie. batteries — and grid support would allow solar to play a critical role.

So, can brute-force battery deployment overcome intermittency?

Let’s do the math.

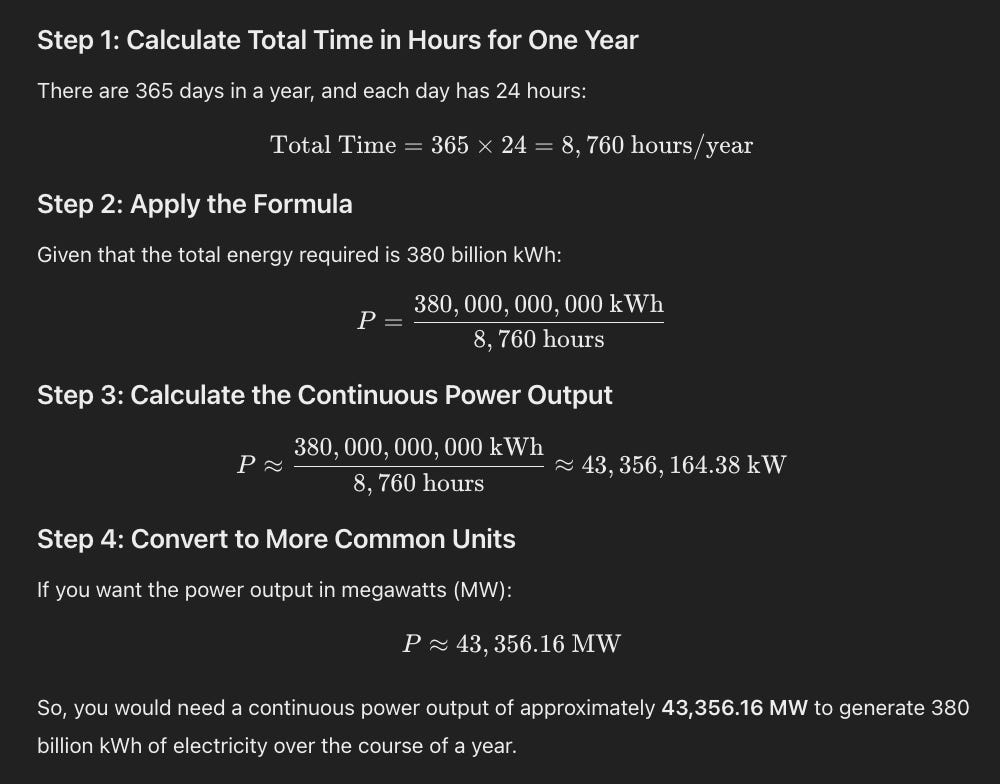

Assume the goal is to power data centers with 100% renewable, intermittent energy, as Huawei recommends. And from the projections above, assume China’s data centers will require 380 billion kWh per year by 2030.

That means data centers will require 43.4 GW of continuous output.3 Assuming each day contains 12 hours of all-you-can-store sunshine and 12 hours with no sunshine,4 and assuming that batteries have 10% energy loss, China would need 573 GWh of battery capacity to cover daily solar fluctuations.

For reference, one gigawatt of electricity is enough to power roughly 650,000 American homes for a year.5

And remember, these are just back-of-the-envelope calculations. In reality, wind energy could provide some nighttime power, but you need battery support to deal with wind inconsistency, too.

Disclaimers in mind, is this level of battery deployment possible? Well … never say never. China manufactured 904.5 GWh of total battery capacity in 2023. Today, Chinese battery producers face staggering overcapacity and an increasingly unfriendly export environment. Those leftover batteries have to go somewhere.

“Although China is building smart grids and adding green energy storage capacity, the process is not fast enough to catch up with the surging power demand in the AI sector.”

~ Chen Gang, Deputy Director of Policy Research at the East Asia Institute

Even if battery deployment is not an insurmountable obstacle, effectively developing grid architecture to integrate this much battery storage will pose an even greater challenge.6

To be sure, in addition to solar and wind, Huawei’s list also mentions hydropower, which is enticing for its ability to provide large amounts of consistent electricity. A recent study found that untapped hydropower could provide as much as 30% of China’s energy needs, and the first zero-emission data center in China (三峡集团东岳庙数据中心) is powered by electricity from the Three Gorges Dam. Beijing has plans to build a mega dam in Tibet’s Medog county, upstream from India — if successful, the electricity generated by this project would be three times that of the Three Gorges Dam.

But even hydropower’s potential is complicated: despite increasing hydropower capacity by 18% over the last five years, China’s hydroelectric power generation has fallen by 1% due to severe drought. That’s putting aside the geopolitical headaches caused by damming up rivers that flow into neighboring countries.

The energy solution that must not be named

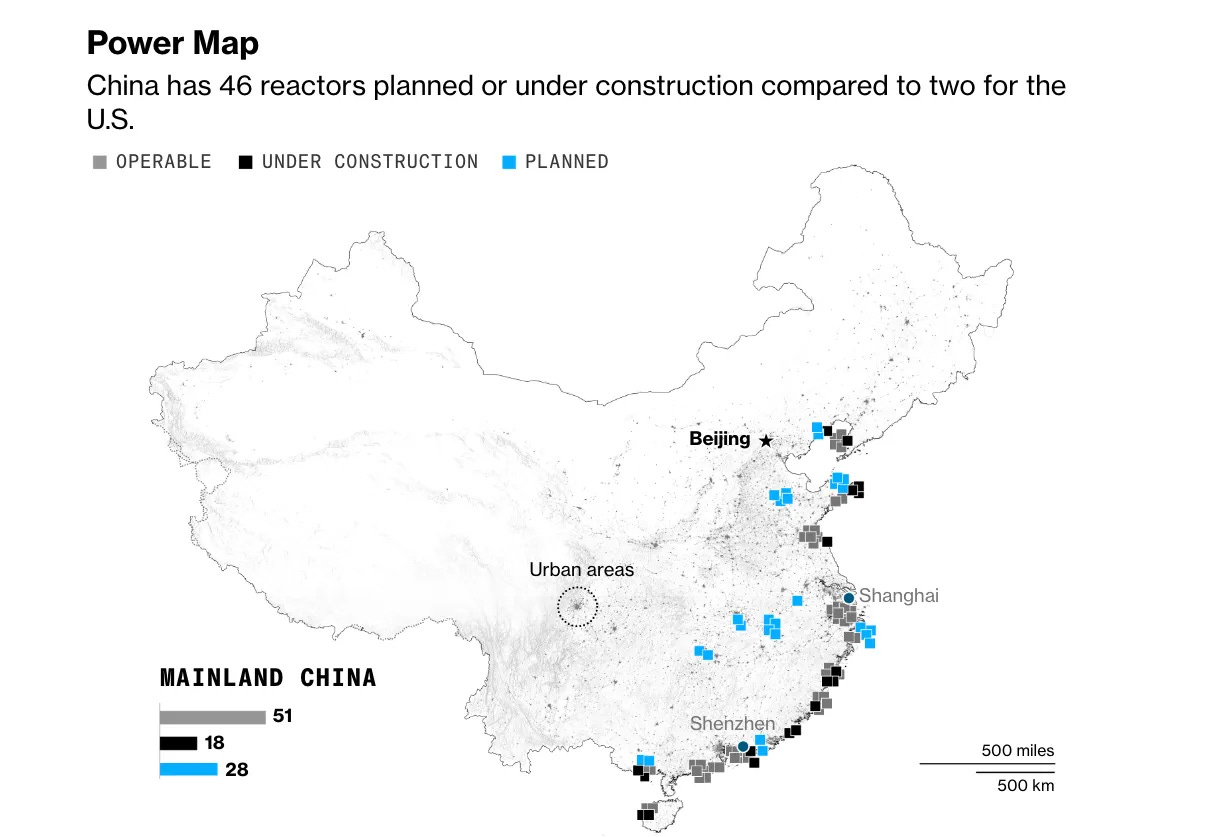

The public EDWC plans do not mention nuclear energy at all, which is suspicious. For decades, Beijing has been aggressively expanding its fleet of nuclear reactors, including plans for a bunch of inland reactors that appear to be in the middle of nowhere. And just the other day, on August 19, China’s State Council approved eleven new reactors in a single day.

Unlike renewables, nuclear power doesn’t suffer from intermittency problems. However, conventional nuclear power plants rely on water for cooling, which isn’t ideal for generating power in China’s desolate desert interior.

But this is by no means a dealbreaker. China leads the world in cutting-edge next-generation nuclear technologies that require no water. China has built successful pilot projects for cutting-edge reactor designs, including sodium-cooled fast-neutron reactors, liquid-salt/gas-cooled thorium reactors, and small modular reactors (SMRs).

Among the new projects approved on August 19th is the Xuwei 徐圩 Phase I reactor, which will be the world’s first commercial-scale high-temperature gas-cooled pebble-bed reactor.7 China’s research on this reactor design began with the explicit intent of eventually building a fleet of nuclear plants in water-scarce interior regions.

Taken together, these innovations indicate that nuclear power could be a dark horse in China’s green compute race.

So why has nuclear power been excluded from the data center discussion?

One possibility is public sentiment. In the late 2000s, anti-pollution protests swept across China. The 2011 Fukushima meltdown made nuclear energy a target and energized protests into a perfect storm — 50,000 environmental protests broke out across China in 2012 alone.

After Fukushima, China’s central government placed a moratorium on approvals of new nuclear plants, and the party spent a year debating whether nuclear power was safe. Provincial officials in the dry, tectonically active western regions did not want nuclear reactors built in their backyards.

Even after the moratorium was lifted, mass protests succeeded in shutting down a uranium fuel plant in Guangdong (2013) and a waste reprocessing facility in Jiangsu (2016).

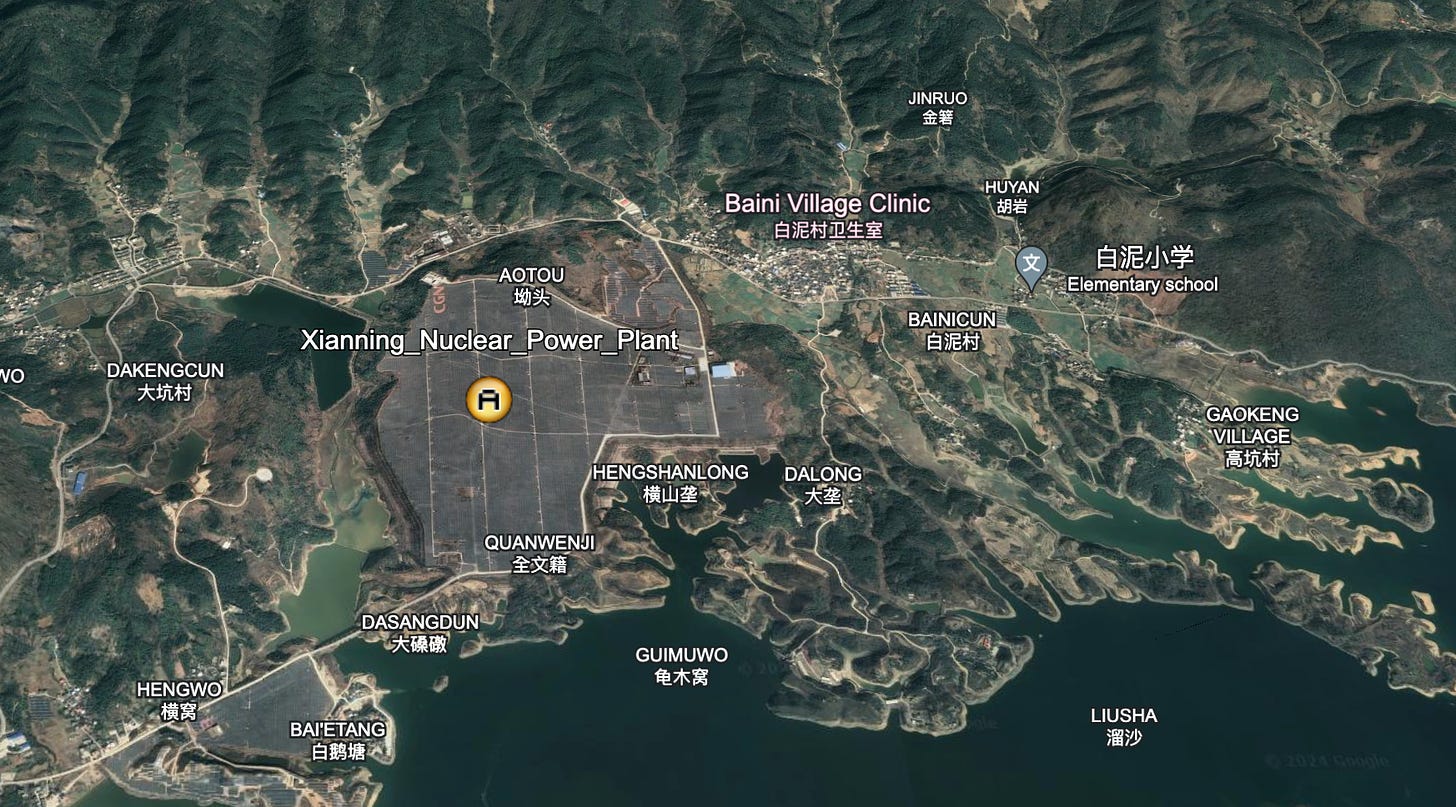

Inland reactor construction never resumed. The flagship Xianning nuclear power plant 咸宁核电站 was heralded as China’s first commercial inland reactor, cooled by water from the Fushui River. It’s been listed as “planned” since 2010 (and appears on the Bloomberg map above), but there’s no evidence that construction ever began. As of 2024, the reactor site appears to have been transformed into a solar farm.

Thus, nuclear could be included in the “other” (等) sources of green power (风电、光伏、水电等可再生能源).

But if that’s the case, the government prefers not to advertise it.8

Perhaps the contributions of nuclear power are already priced in. Even if Beijing can’t build inland reactors for some time, adding conventional nuclear power plants near the coast makes the whole power grid greener. Computing from China’s western regions draws power from the broader grid, so even the distant conventional reactors will help fuel the power-hungry data centers.

But there’s another explanation for excluding nuclear power: maybe China isn’t actually serious about making data centers green.

That would be majorly bad news for the climate, and ChinaTalk will be reporting more on that possibility in the future.

Make It Efficient

To manage the energy demands of data centers, the second key component is increasing efficiency. Due to US sanctions, advanced chips like Nvidia’s Blackwell may be out of reach for China.

Data centers, however, have plenty of cuttable energy overhead.

A primary measurement for evaluating data center efficiency is power usage effectiveness, or PUE — the ratio of the overall energy used by a center to the energy used by the compute resources. The ideal ratio is 1.0; the lower the PUE, the more efficient the data center is.

At the end of 2022, China had 153 “green data centers,” with an average PUE of 1.27. However, 85% of China’s data centers have a PUE between 1.5 and 2. (For reference, Google’s data centers average 1.10.)

The Chinese government has set a standard for new large-scale data centers: achieve a PUE of 1.3 or less — otherwise, they will face elimination (不达标的数据中心将面临淘汰).

Potential avenues to improve PUE include opting for stripped-down “hyperscale” data centers, assigning compute tasks more efficiently, optimizing site selection, and halting model training early. But China is also exploring the commercialization of relatively new and yet unproven technologies like submerged chips.

Broader Criticism

Chinese commentators have questioned not only the technical feasibility of building green data centers, but also the underlying economics. In April 2022, Chen Gen 陈根, a guest lecturer at Peking University, argued that the government-led buildout of high-efficiency data centers ahead of demand would artificially decrease prices and lower profits, thereby hurting tech companies.

Another Chinese researcher, Wang Yuanzhuo 王元卓, argued in a March 2022 piece that the initiative should focus on demand-driven applications:

From past experience, the high social interest and economic benefits of national-level projects easily produces “bandwagoning” and “blind construction and investment,” as seen in new energy vehicles and chip manufacturing, resulting in unfinished projects and even harm to local economic development.

从过去的经验来看,国家级工程因为社会热度高、经济效益好,很容易出现各地“一哄而上”“盲目建设投资”的情况,新能源汽车、芯片制造都出现过这样的情况,最后出现了烂尾甚至影响到地方经济的发展。

These fears are not unfounded. When rolling out new computing initiatives in 2021, one of the government’s stated goals was to increase the utilization of western data centers from 30 percent to more than 50 percent — which indicates a lack of commercial demand for the data centers already built in the west. Adding additional capacity without making those data centers more commercially desirable is unlikely to accomplish much.

The Push Continues

Solar, wind, hydro, and nuclear energy all face significant challenges as Beijing seeks to build a unified national computing network (全国一体化算力网). Just as in the US, China has no easy answer to the impending bottleneck — hence the highly public conferences held in June and August of 2024 dedicated to brainstorming solutions to this juggernaut of a problem.9

Some argue these percentages are overblown and point to increased efficiency as potentially offsetting the increase in electricity required.

This was likely less of a brilliant future insight, and more of an opportunistic approach to deploy renewable energy in western provinces, increase western economic development, and reign in uncoordinated efforts by local governments to jump on the data center bandwagon.

Here, we are excluding wind from the calculations altogether. Leave us a comment if you would appreciate more rigorous calculations, or if the 差不多 math is enough.

Assuming an average of 650 homes per megawatt, given the range is 400 to 900, according to this report by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Microgrids are also touted as a potential solution. One pilot project, “The New Energy Microgrid Project of the Green Energy Center at the Zhangbei Cloud Computing Base in China” 中国张北云计算基地绿色能源中心新能源微电网项目, is currently underway — revealing substantial technological difficulties in the process. Major infrastructure developments would be necessary to make wind or solar the backbone of data center projects.

The first ever gas-cooled pebble bed reactor was China’s Shidaowan demonstration plant, which only has 200 MW of installed generation capacity. The Xuwei plant will have a maximum power output of more than 1300 MW between one high-temperature gas-cooled reactor and two pressurized water reactors, with 600 MWe coming from the gas-cooled reactor.

The major conference in June was titled, “2024 China Green Compute (AI) Conference” 2024中国绿色算力(人工智能)大会, and spearheaded by Tsinghua University and the Horqin Green Compute research center in inner Mongolia.

On August 29th, a similar event was held on the topic of “Market Development in Electric Computing Power Collaboration and Data Fundamentals,” “电力算力协同暨电力数据要素市场发展”交流活动. This event was organized by the China Southern Power Grid Corporation (SOE), China Electricity Council, and China Academy of Information and Communications Technology.

Delaying the nuclear construction program after 2011 to build more coal power plants instead was a bad decision, much more health impact this way since nuclear plants are way ceaner than coal plants.

Good info. Thx. Always interested in is their system of government better or is our bottom up system better? Many times I wonder? They always seem to have a plan and we don't.

We just seem to be good at social causes?