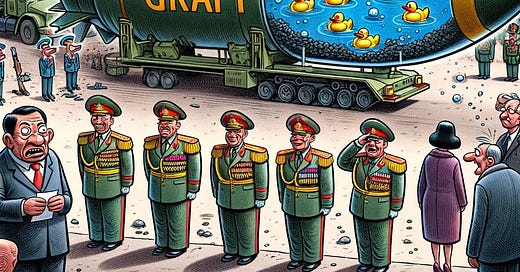

Bloomberg reported Saturday afternoon that Xi Jinping’s 2023 high-ranking PLA purges were prompted by corruption so pervasive that (per US intelligence assessments) Xi is now “less likely to contemplate major military action in the coming years than would otherwise have been the case.”

In particular:

The US assessments cited several examples of the impact of graft, including missiles filled with water instead of fuel and vast fields of missile silos in western China with lids that don’t function in a way that would allow the missiles to launch effectively, one of the people said.

Of course, none of that is surprising to paying readers of ChinaTalk! We brought Joel Wunthow onto the show back in October — the day after Li Shangfu 李尚福 was purged — to discuss the PLA’s structural, endemic problems with corruption, as well as how we should understand the threat to Taiwan.

Key insights from that paywalled episode we’re running below:

Making predictions about Xi’s calculus or timeline on Taiwan is really, really tricky;

The PLA’s timelines are moving goalposts and should be taken as such;

China may be taking the lack of Western boots on the ground in Ukraine as a good sign for its designs on Taiwan — but that may be the wrong lesson to draw;

Taiwan needs to shore up its own deterrence capabilities — to prove to China that it can defend itself before help arrives from the US or others;

For Taiwan, this means spending more across the board, developing and maintaining destroyers and planes, and investing in cheaper one-off tech like armed drones.

When and How Might China Invade Taiwan?

Nicholas Welch: In the assessment of people like Oriana Skylar Mastro, the thing which matters most for a decision over Taiwan is Xi Jinping’s perception, not China’s missile count or anything like that. If Xi perceives that an invasion is plausible or could be successful, then that’s the only thing that’s really going to be driving him.

Is that the right way to look at it?

Joel Wuthnow: Well, it’s part of his calculus. Does he think that, operationally, they will win? If they invade, will they get a foothold? Will resistance crumble? That’s part of it — but part of it is also, “Could this be a Pyrrhic victory for China?”

China might get the immediate prize [control of Taiwan], but suffer such huge economic, political, and military damage to get there that it’s just simply not worth the benefit. That would have to be weighed as well.

Yes, perceptions matter, as does how Xi is thinking about the economic damage and about sanctions. Does he conclude that China has inoculated itself against what the West did to Russia? So does he think about that piece? Does he think about his political survival? Let’s say that I roll the dice on this and it goes badly — are there people that are going to pull their knives out? So all of these questions get to his mindset, and we have to ask them, because Xi is the pivotal decision-maker.

But our confidence in the answers to those questions has to be really low, because none of us really know him. All we know is his pattern of behavior and the speeches that he gives to date. You can try to make inferences, but you could still be surprised by someone who is going to act in a totally different way than you expected for unknown reasons.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about the pattern of behavior, which is one of the things that is making me a little less scared of World War Three than other folks.

So Putin invaded Ukraine in February 2022, but he also invaded Ukraine in 2014. He invaded Georgia. He fought a whole giant proxy war in Syria, also had some fun in Azerbaijan. This is a man who has a long and demonstrated track record of rolling tanks across borders.

Xi has also been around for a while. Say what you want about the Scarborough Shoal[an area in the South China Sea disputed between China and the Philippines] and what happened with India [frequent skirmishes over the border], but I think there’s a real argument to be made that an invasion of Taiwan would be a very different kind of operation. To get to that level of overconfidence, you probably need to win some small wars, unless you’re starting to lose it or some other exogenous shock is happening — maybe some internal political struggle where you want to reassert control over the PLA by having a foreign adventure. So it feels like Xi would need to work himself up to the big one — I would hope so, at least.

Joel Wuthnow:

Right, Xi is not Putin. He has tried pretty carefully over ten years to stay below the threshold of lethal violence, because I think he worries about the accumulating effects of sanctions. He worries about a debacle that makes him look bad. Besides, he wants regional stability for economic growth, which is the core to his legitimizing story.

You can’t exactly deliver the goods to the people if you’re at war with Vietnam or Japan or India. That has been his track record, and I think that does give people confidence.

However, it’s a black-swan realm: you are building the tool to invade. You are trying to inoculate your economy from sanctions. You are doing the things that you would do if you want to at least give yourself the option in the future of moving beyond that threshold. So that’s why people worry about it — because Xi hasn’t been that transparent about what his intentions are.

Xi uses the language of peaceful reunification, but what are China’s options to achieve it? There are very few. So is there going to be a point in which his calculus shifts? At such a point it could be an advantage not to have waged a bunch of small wars, because people could say, “We’re genuinely shocked and surprised and paralyzed, because we didn’t see it coming.” And it becomes the next great intelligence disaster for the West. And China might pull this off better than Putin’s attempt to cloud his intentions by means of an exercise in February of last year.

All of that is to say — there is an alternative. It’s not necessarily a likely alternative, but I think it’s one that is worth worrying about. And because it’s possible, that is what is justifying Taiwan’s defense reforms and US deterrence.

Jordan Schneider: I just finished reading Zubok’s Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union, which tells a very detailed story, from 1985 to 1993. At a certain point, Gorbachev said, “I am going to sign the SALT to end all SALTs, and voluntarily withdraw forces from Eastern and Central Europe.”

There was this incredible moment where meetings began between Western business people and the leaders of the Soviet military-industrial base, with the latter saying, “We want to stop making missiles, and thanks to the Soviet command economy we only know how to make bicycles. Meet us somewhere in between. Teach us how to make microelectronics that are useful for the rest of the world.”

That is so many more degrees more comforting than someone who’s talking about 2027, 2035 and 2049. How should people think about these dates? What is the right conceptual framework to apply to them?

Joel Wuthnow: I think the right way to think about these timelines is that the PLA needs to be told what to do — because if they’re not given dates and they’re not given targets, then they’re going to be spinning their wheels and complacent and distracted by their corrupt schemes. So starting from Jiang Zemin, Party leaders had to tell them, “Look, by 2010 you’re going to do this, by 2020 you’re going to do that.”

They keep needing to revise the dates because of the passage of time. So people have obsessed about this 2027 date, but the PLA needs it. It’s their near-term readiness goal. 2020 was the last one; it came and went, so they need a new target.

The misconstruing of this is that the CCP has some political timeline to resolve the Taiwan question, and that it has to be by 2027. That’s not how the PLA or Xi Jinping is talking about this at all.

They’re concerned with modernization, and wanting to have options sometime this decade because they don’t currently. But it’s not to say that they have a secret timeline, and that by 2027 they need to invade Taiwan, and that’s final. I think that’s a total misconstruing of the evidence and the history.

Invasion Scenarios and Lessons from Ukraine

Jordan Schneider: There’s another way in which you can manifest timelines if you’re running a military and you’re thinking about budgets. There are three levers you can press:

You can increase size,

You can increase the material that you have available now and in the near future,

Or you can invest in R&D to make sure that, ten years from now, your tech is going to be up and ready.

Do you have a sense of how those three curves of investment are playing out?

Joel Wuthnow: About five years ago, the procurement — the long-term R&D — did peak. It was about 40 percent of the budget, which was over $200 billion. It has started to come down, and it’s come down maybe five percentage points or so.

The reason for that is they’ve built this huge arsenal which has to be maintained. If you’re pumping out new ships and planes all the time, those things start to rust, their engines fail, and so on. So that near-term readiness account has been growing by about 5 percent as well. I anticipate that pressure is just going to continue, because it’s not cheap or trivial to maintain and keep your forces trained up.

The other piece you mentioned is about the size of the force. Xi Jinping did cut the PLA when he came into office. It’s at 2 million now, but the personnel expenditures are about equal — as a percentage of the budget — to what they used to be.

So in other words, Xi has fewer people, but he’s paying them the same share of the budget. What that shows you is that people are more and more expensive in China — to hire and to keep in military service. He’s not just coercing people into uniforms, so he’s having to pay them more. That itself is putting some pressure on the budget that might not be going to long-term R&D as well.

Nicholas Welch: I recorded a show this summer with Paul Huang. His take was basically, “Any defense analyst who says that the PLA is going to launch an amphibious invasion doesn’t know what they’re talking about. It can’t be done. It’s impossible.” That aligns with the Office of the Secretary of Defense 2021 report onamphibious invasion. They don’t say it’s impossible, just that it’s one of the most difficult military operations you could ever do.

In a recent publication you put out, you mention one option — what you call a “joint firepower strike campaign,” which is what Paul Huang talks about as well: firing a whole bunch of missiles to try to force Taiwan to acquiesce to the PRC’s terms before a long war is brought about.

Do you have a take there? Is an amphibious invasion just totally out of the picture? What would an incursion against Taiwan actually look like realistically?

Joel Wuthnow:

Realistically, no, I don’t think that an amphibious invasion is totally out of the picture. They’re still training for it and trying to find ways to make up for some of the problems.

For example, they are bringing civilian ferries into their training because they don’t have enough ships to carry the troops and carry the equipment across the Taiwan Strait. So they’re experimenting right now. It’s not going to look like Normandy 1944. It’s going to look like the 2030s: a lot of missiles, a lot of airborne troops coming across, some people coming across in ships after the critical anti-air and anti-ship threats have been eliminated. So it’s not out of the picture.

What Paul is talking about is a massive missile bombardment designed to make Taiwan’s leadership — if they survive — feel extremely vulnerable so that they’ll come to the negotiating table. That’s an option the PLA could choose today. They have so many missile forces arrayed against Taiwan that they could just pull that lever right now if they wanted to.

One reason they haven’t done that so far is that it doesn’t guarantee victory. Unless you’re going to send boots across the Strait and occupy territory, then you are leaving your adversary in place to some degree. So that’s number one. And number two, you’re going to pay some of the cost of a war to do that. You’re absolutely going to kill people by doing that. And once you cross that threshold, then you run the risk of facing sanctions. It means paying the cost of a war without getting the guaranteed victory of a war, which doesn’t seem like a great choice.

The other option is the blockade scenario, and that’s also something they could do, or at least within a certain margin of risk, they could try to do it. They haven’t done that either, because like the missile bombardment, it doesn’t guarantee anything. It puts a huge amount of pressure on the adversary, but wouldn’t guarantee that Taiwan would do what they want.

Jordan Schneider: And I think one of the lessons from Ukraine is that this sort of military adventurism can backfire and make people more enraged than they already were.

Joel Wuthnow: People talk about a blockade because they say it’s less escalatory — just using the Coast Guard to stop ships. But then what? The other side — meaning Taiwan, potentially the United States or Japan — might decide that they’re going to run that blockade. And then China would have to decide whether or not to sink the blockade runners. At that point you’re getting into a war — and that’s very escalatory.

So there are reasons why China hasn’t gone down those paths. They may seem attractive on paper, but once you start dealing with bullets flying and missiles being shot and so on, then you don’t know what the outcome is going to be. And the CCP and Xi Jinping would want to know how this might end with 100% confidence, which is not possible.

Jordan Schneider: Are there any more operational-level lessons that you think Beijing is starting to key into when it comes to Ukraine?

Joel Wuthnow: What China is observing is that Russia isn’t getting away scot-free — with sanctions and arms flowing into Ukraine — but there are no boots on the ground and there’s no no-fly zone. I think from Beijing’s point of view, this situation is in place because of the nuclear deterrent.

At the outset, Putin warned that things could escalate very quickly if you get involved in our core interests. China’s seeing that the West was easily deterred. You say the word “nuclear” in a press conference, you fly a nuclear bomber around, and presto chango! — you get no foreign intervention.

So China is building this massive nuclear arsenal: bombers, ships, you name it — they’re going to build it. And they’re saying, “This could be very useful: we may not actually have to fight the Americans, which is not the desired outcome; we may be able to keep them at arm’s length.” So the idea that they can narrow the conflict to one just between them and Taiwan, with no third-party intervention, is an attractive outcome — maybe slightly overly attractive one.

I think that’s the major lesson China is drawing from Ukraine — and I think it might be a wrong lesson, because I think there’s a higher chance that the US would get involved in Taiwan compared to Ukraine.

Regional and Allied Deterrence

Jordan Schneider: Speaking of making that deterrence capability clear: Biden has started to be a lot more explicit about America’s commitment to Taiwan, as well as increasing the human tripwire by putting more and more American military trainers on the island.

Any thoughts about the other levers that Congress or the executive branch could pull in order to increase the deterrent capacity — as well as what risks you potentially see on the horizon for that degrading over time?

Joel Wuthnow: Taiwan needs to stockpile a whole lot more munitions than they have.

We sometimes talk about the center of gravity — what’s really going to make the difference for Taiwan in terms of their confidence levels and ability to mow down anything trying to get across the Taiwan Strait. That’s the center of gravity. But if you don’t have enough anti-ship missiles, if you don’t have enough Stingers, if you don’t have enough sea mines and the ability to deploy them quickly — that’s going to erode deterrence. Taiwan does not have enough of those things. They are going to either build them or purchase them from us. But stockpiling is really important.

The other blindingly obvious distinction with Ukraine: Taiwan is an island. We’re not going to be sending in convoys in the middle of a war as easily as sending stuff across the border with Poland.

Taiwan is going to need a lot, whether it’s munitions or fuel, to keep their military running. They need a lot of help with that right now, and finding a way to get that aid to them while simultaneously supporting Ukraine has been a major conversation.

What’s going on in Taiwan with their defense reforms is worsening the problem. How committed are they to sharpening the sword that the PLA would be running into? That’s a whole other set of questions — it makes the whole thing more complicated.

Nicholas Welch: On the deterrence front as well — are there more creative ways we can think about this problem? For example, China is surrounded by fourteen other countries. In a Foreign Affairs piece you wrote last year, you mentioned the possibility that India may seek to take advantage of a Taiwan contingency to reclaim the territory it thinks it lost in western China.

First of all, to what extent do you think that’s a real deterrent effect in the PLA’s mind? How much would that influence whether or not they engage in Taiwan?

And to what extent can those kinds of options factor into deterrence as Western nations think about how to go about it?

Joel Wuthnow: The Chinese call this “chain reaction warfare.” They’re saying that if war breaks out in the main theater, somebody else is going to take advantage of that to kick China while it’s down. That could be India, could be Japan, could be Vietnam.

China worries about that, and because of this worry they’re distributing their military capabilities to all their different theaters. They think they need to have a very high level of readiness in the west, in the south, in the north, even as they’re going to war in the east.

Do they think that they’ve gotten to the point where they’re able to deter adventurism by another country? I don’t know if they’re there yet.

Let’s say the war escalates and it gets protracted, and they need to draw material from other parts of the country to the main theater. That’s a limitation for them — if they need to keep a lot of people in place against India, Japan, or Vietnam. I don’t know that it’s central to deterrence.

I think it’s a complication for them, because I do think that deterrence wins or fails based on what they think they’re going to face right across the Taiwan Strait. It’s proper to focus on that, but this definitely complicates their problem. It reduces the amount of forces they can throw into the main battle. But I don’t necessarily think that’s going to be the pivotal piece of a deterrent in a crisis over Taiwan.

Jordan Schneider: I want to ask you about the importance of Taiwan’s military capabilities. We’ve talked earlier about how important the American commitment to Taiwan is as a deterrent. But Taiwan talks about how it could hold out for one month or two months or four months. To what extent does that length of time matter in a broader strategic sense?

Joel Wuthnow: It definitely matters because Taiwan is going to have to hold out for some period of time if they’re attacked, because the US military and others are not right there. So there needs to be time to mobilize. If it’s a large conflict, that could mean sending ships across the entire Pacific Ocean, which takes weeks. So they have to be able to hold out to some degree.

China, meanwhile, is trying to figure out how quickly it can get this done. If you can present your adversary with a fait accompli, then it doesn’t matter.

China is talking the language of speed — of very short duration and high-intensity conflict. They want to get it all over and done with.

But it’s important for deterrence that Taiwan broadcast its ability to put up a fight, knock out some of the planes, some of the ships, and buy themselves time. So the time equation absolutely matters.

The other piece is: what’s the regional situation? The US has a lot of combat power in Japan, South Korea, potentially in the Philippines. Will that be helpful or not in a conflict? It’s much closer than coming from San Diego or even Hawaii. So is China willing to strike those targets and risk bringing those countries into the conflict knowing that it must be done in order to protect their operation?

There are many different variables in the equation that it makes it hard to predict.

Is Taiwan Spending Enough, and on the Right Things?

Jordan Schneider: Thirty years ago, China and Taiwan basically spent the same amount on military forces. But now it’s something like 12 to 1. How useful are the marginal increases on the Taiwanese side in extending that one week, to one month, to two months for the Taiwanese military to potentially resist an invasion?

Joel Wuthnow: It really depends on how they’re spending it. The latest announcement was that they’re up to 2.6 percent of GDP — or will be next year. If they’re putting all that into Stingers, then I think that’s fantastic. If they’re spending all of that on a fighter that’s going to be obliterated on day one of the conflict, not so much.

When you had Paul Huang on, he was critiquing Taiwan for spending way too much on large, high-value conventional forces because they’re not useful in wartime. I agree with that, and that’s been a message to them for a long time. What they would argue is that you need those capabilities in order to beat back even regular peacetime coercion.

You can’t intercept a fighter with a drone, you can’t intercept a ship with nothing. You have to have destroyers, you have to have planes, and they have to be functional. You can’t just have old things that are breaking down all the time; you have to upgrade them.

But the question is: where’s the right balance? Between peacetime and safeguarding your own sovereignty on one hand; and then buying what you actually need to defeat them or to delay them in war. Are they finding the right balance? A lot of people will still say Taiwan is unbalanced. I still count myself as a bit of a skeptic on that front.

Nicholas Welch: I hear people in Taiwan and the US say basically the same thing: they’re not buying enough asymmetrical capabilities or “large numbers of small things.”

It seems as though both are aware of this — but Taiwan last week instead rolled out their first homegrown submarine. They like these new projects. Do you have any sense of why we’re not able to just send more munitions to Taiwan?

Joel Wuthnow: There are different reasons. Part of it is that the US defense industrial base isn’t producing very much of it anymore. The factories have been mothballed, the workers are not trained for it, and there’s been no demand for it until very recently. So restarting some of that is very important.

Obviously the other constraint is that some systems have been prioritized for Ukraine. Finding bureaucratic and industrial ways to ramp up production and shift it to where it’s needed is important. But I do think that right now, Taiwan needs to look at alternatives. They have to be able to cheaply produce — potentially from the private sector — things like armed drones, things that you can 3D print and throw up in huge numbers, and that are basically for one-time use. There’s no reason why they can’t do that.

Our DoD just released this thing called replicator about a month ago. It’s the idea that you want to have a huge number of drones to overwhelm your adversary by mass, and it’s eminently doable. Taiwan can have their mini-version of that — just throw up enough armed drones that might cost $1,000 each at an invading fleet. Some of them are going to get knocked out, but many of them won’t. And that’s very helpful in the near-term.

So they need to think creatively and not get stuck in this bureaucratic mindset that the only thing that’s going to save them is a billion-dollar submarine. That’s not the case.