R&D Renaissance with Kumar Garg

Philanthropic R&D for human flourishing and national competition

To discuss America’s comparative advantages in national competition and the structural forces that drive (and limit) innovation, ChinaTalk interviewed Kumar Garg.

Formerly an Obama official in the Office of Science and Technology Policy, Kumar spent several years at Schmidt Futures focusing on science and technology philanthropy. He has been a mentor and cheerleader for ChinaTalk over the years, and he is the president of the newly established Renaissance Philanthropy.

We discuss:

The inspiration behind Renaissance Philanthropy and its focus on mid-scale, field-transforming ideas

Strategies for identifying underexplored, high-impact projects — including weather forecasting, carbon sequestration, and datasets on neurocognition

Structural challenges for R&D funding at the level of government and universities

The role of focused research organizations like OpenAI in accelerating progress and understanding long-term drivers of productivity

A wide angle-view of US-China competition and strategic innovation

The underresearched importance of alliance management.

Spotify:

Apple Podcasts:

The Classical Innovation Model

Jordan Schneider: Tell us about Renaissance philanthropy — what’s the backstory and thesis?

Kumar Garg: Renaissance is a young organization. Our name and thesis harken back to the Italian Renaissance. We’re inspired by how wealthy Italian families played an outsized role in supporting innovators, scientists, and thinkers like da Vinci. We’re exploring the role wealthy patrons can play today in driving a 21st-century renaissance.

There’s enormous untapped giving potential among today’s wealthy families. A study of 2,000 families with large fortunes showed they’re giving less than 2% philanthropically.

When asked why, they often cite two reasons: they’re still actively working and plan to give later, or they haven’t come across exciting ideas. These reasons stem from the same issue — they’re busy and not encountering compelling opportunities.

Rather than waiting for donors to reach a later life stage like Bill Gates, who exited his career to focus on philanthropy, we want to engage them earlier. In science and tech, it’s challenging to be strategic by just interviewing individual researchers, who are trained to pitch their next project rather than discuss field-wide challenges.

Earlier today, I was talking to somebody who was explaining the advances in neurotechnology. We have new methods and tools which should allow us to understand the way the brain works. At a technical level, these tools didn’t even exist three to five years ago. Now, we could actually build high-dimensional data sets that could allow us to understand the whole brain in a model organism.

The dataset they want to build is just too big for individual research projects, but it’s also too small for a major university capital campaign. These ideas often struggle to get funding from research agencies like NIH because they fall outside the scope of individual investigator awards.

Renaissance aims to identify these big mid-scale ideas — three to five-year efforts that could unlock a field — and match them with donors excited about the thesis. We want to draw more people into strategic giving by presenting them with exciting hypotheses and teams to support.

Jordan Schneider: How do you source these ideas and find CEOs who can execute $10-30 million projects? What should potential applicants from the ChinaTalk audience know?

Kumar Garg: Interested individuals can reach out through our website (or email info@renphil.org). We’re looking for ideas that go beyond incremental research steps to strategies that could accelerate entire fields.

We start with a field-level view, asking what strategies could help us progress faster. This requires identifying roadblocks, bottlenecks, and areas that are less incentivized for individual researchers but highly beneficial for the field.

When interviewing researchers, we often start by discussing datasets. Creating high-quality, multidimensional datasets is valuable for the community but not always rewarded in the current system. We ask researchers to describe dream datasets that could accelerate progress in their field, then work backward to determine what’s needed to create them.

We also look for projects requiring close collaboration between researchers from different disciplines, which can be challenging to fund through traditional channels.

Another approach to locating gaps is working backward from important problems. For example, famed UChicago economist Michael Kremer made a general observation that AI is improving weather prediction.

Michael spends a lot of time working on sophisticated economic models, and one of his research areas is smallholder farmers. [Ed: Professor Kremer won a Nobel Prize for his contributions to development economics in 2019]

He considered how AI could benefit smallholder farmers by more accurately predicting monsoons. If you can predict monsoons farther in advance, that could potentially increase crop yields significantly in a whole bunch of countries, such as India. Farmers could figure out when they need to harvest their crops before the rains come. Because as an economist, he could estimate the economic value for that increase in the accuracy of monsoon prediction.

Once the value is written down, then it’s clear that somebody should fund this. It’s not just general improvement in weather prediction — this particular use case has really high social value. But those individual farmers left on their own will not finance that AI improvement. Somebody has to step in and say that aggregate value is really valuable.

To find a donor for projects like these, sometimes the gap is on the demand side — the demand is latent, and you need to define it to pull people in. Sometimes the gap is on the supply side, where certain types of organizational behaviors are undervalued, like data sets.

We are often just asking good questions — “How would we go faster, bigger, better in your field? Are those big ideas hard to fit in the current funding landscape, and if so, why?”

Writing down those details makes for a very strong application.

Jordan Schneider: This seems like a lot of work for you. Is there a way to do this besides just talking to many people? What’s the non-artisanal version of coming up with these ideas?

Kumar Garg: Creating archetypes for this way of thinking is essential. I was partly inspired the work I did with Eric Schmidt creating an organization called Convergent Research, which works with focused research organizations (FROs).

With Convergent Research and the FRO model, Adam Marblestone initially received meta-feedback on his paper about focused research organizations. Once we got some FROs funded and scoped, researchers could see concrete examples and generate ideas that fit the model.

Adam now has a list of 300 FRO ideas, not because he had 6,000 conversations, but because people are coming forward with ideas that fit this model. Our job is to assess funder demand for these ideas and potentially share them with agencies like ARPA-H.

Building out the right set of questions and showing replicable examples will be crucial as we launch various funds, enabling people to envision applications in their fields.

Jordan Schneider: Focused research organizations may sound nebulous, but OpenAI is a prime example. They started with Sam Altman declaring no clear path to profitability, focusing solely on making models smarter. With limited initial funding, they took risks that weren’t being made in academia, DeepMind, or Microsoft Research. It’s a great case study of what scientists can achieve under different institutional structures and incentives, freed from mainstream corporate R&D or traditional academic funding constraints.

Kumar Garg: It’s challenging in the modern university system. While individual researchers build labs with various related projects, the idea of collaboratively solving one mega problem requires both a structure and funding that accommodates it. This approach can have a huge impact, but it’s difficult to implement within traditional academic frameworks.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s consider the individual level. Does this require leaving the tenure track or a comfortable position? Who are the people who go from having a good idea to actually implementing it, potentially taking a lateral step in their career?

Kumar Garg: You find people at different levels of the spectrum, but a common trait is the ambition to move their entire field forward. There are several ways to approach this:

Agenda setting: Researchers can take a step back, identify transformative ideas for their field, and share them compellingly with private or public funders.

Government rotations: Top researchers can spend time at agencies like DARPA or ARPA-H, bringing their orientation to find the next generation of bets.

Alternative roles: Some researchers enjoy running labs but also want to push coordinated research programs with key results. They might become DARPA performers, FRO CEOs, fund managers, or startup founders.

The challenge is that these alternate models often feel invisible or difficult to pursue. We try to make these paths more legible by providing clear examples and explanations of different roles, such as running a focused research organization or becoming a DARPA program manager.

By making these alternate paths more visible and understandable, we can encourage more innovation in career paths, similar to how the concept of being a startup founder has been popularized and made accessible to more people.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting because most of the time, you still need the person to get a PhD first. That process socializes you in a very particular direction. In early science, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, not everyone in the field had to go through this seven-year process where they couldn’t see the forest for the trees due to living under all these constraints. It takes an unusual person to be in that environment for 5, 10, or 20 years and still be able to recognize that everyone’s doing X, but if someone did Y for a while, it could have an incredible multiplier effect.

Kumar Garg: You raise a fair point. The computer science community is having an outsized impact partly because of AI’s rapid development, but also because of the field’s inclination. Not everyone gets a PhD, yet they can still do cutting-edge work. These individuals are now filtering through the broader science ecosystem, bringing down the average age of researchers.

Erika DeBenedictis figured out the importance of peer networks among young researchers when working on research automation. These networks can be leveraged to promote new ideas and tools. For example, to encourage more young biotech founders, engaging with the research networks of young biotech researchers and introducing the idea of founding a company can be effective.

These emergent talent networks are probably underexplored. This relates to the Renaissance point about the social networks that drive progress. In Leonardo da Vinci’s era, many interesting people were illegitimate sons of nobility who had access to resources but lacked predetermined social obligations, allowing them to forge their own paths.

The science community will always benefit from attracting people who want to go off the beaten path, but we also need to build more paths to make it less challenging for them.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss the donor side. What range of net worth is worth 30 minutes of your time? Why do you think this approach resonates more than other options available today?

Kumar Garg: My involvement in philanthropy was somewhat serendipitous. While working in the Obama White House on science and tech policy, I realized that while the government brings enormous scale to its initiatives, the early work of identifying opportunities and organizing workshops is often too early for major federal agencies to get involved. This is where funders can play an outsized role.

Philanthropy and donors play a crucial part in an ecosystem where most R&D funding comes from the government. However, donors can contribute significantly to agenda-setting, identifying major opportunities, fostering interesting collaborations, and addressing overlooked areas.

Catalytic capital can have an outsized impact when used effectively. We’re at the beginning of unlocking this capital, and most of the giving that will happen hasn’t occurred yet. We have a huge opportunity to capture imaginations and harness resources for big public goods and ideas that solve problems.

When talking to donors, donor advisors, or staff members, I often help them understand that there is important work to be done. Many people feel paralyzed when faced with large-scale issues like climate change, where the government is already spending huge sums. The key is to provide them with a mental model at a more micro level of what’s not being done that could make a significant difference.

For example, we provided early funding for enhanced rock weathering, a climate solution that wasn’t widely known two years ago.

Basically you can break up certain types of rock and actually use it as fertilizer and it actually functions as a carbon sink and as a fertilizer. I remember having this conversation with Eli Dorado a few years back where he recommended we look at enhanced rock weathering.

Those early grants from a small set of folks helped get that subfield going. Now, through the work that Stripe is supporting, this is considered a pretty important technology that might help with carbon approval. There are donors who work on smallholder farmers in Africa who feel this might be a core part of their strategy and increase farmer income.

Giving people examples — and a sense of confidence that their ideas didn’t just miss the boat entirely — shifts their mental model.

“We are figuring out new things. They’re going to be important to solving big problems, and you can help figure those things out.”

It pulls them in. My hope is that they get addicted to it, and their core motivation becomes making the world a better place. We all benefit from that.

Jordan Schneider: It’s fascinating how your career experiences have led you to this point. You needed to be part of a behemoth organization to see its blind spots. The same goes for PhDs who become frustrated when they enter government.

Your background, including working for one of America’s wealthiest individuals, presumably helps when pitching to donors. What you’re proposing is fundamentally a high-variance, unconventional idea that isn’t typical philanthropy, like donating to Massachusetts General Hospital. It’s something that other philanthropists, such as those at the Hewlett Foundation, have overlooked when it comes to climate issues. It’s an interesting combination of factors that brought you here today.

Kumar Garg: Indeed. I benefit from seeing the system from various perspectives. This is why I recommend people enter government or move between different sectors, becoming “tri-sector athletes.” It broadens your understanding of what’s possible and what’s missing.

One of the real blind spots in science and tech funding is that people often start from basic first principles, asking if an idea is good. However, if you’ve spent time in government, you’d ask why the government isn’t funding this idea if it’s so promising. There’s usually an entire agency dedicated to funding good ideas in a specific field. This line of questioning leads to interesting insights.

For example, I spoke with a venture capitalist in early healthcare who wasn’t familiar with NIH’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program. When I mentioned that SBIR’s funding matches the VC investment in early-stage healthcare (about $2 billion each), it raised questions about potential disconnects between government funding and commercialization efforts.

Being curious about why systems work the way they do and why certain opportunities are missed can lead to significant breakthroughs. You’re dealing with substantial funding flows, so understanding these dynamics is crucial.

Jordan Schneider: We’ve discussed the structural issues in government funding. Regarding established philanthropies involved in climate or science and technology, where do you see structural oversights in their programs and among their program officers?

Kumar Garg: Looking at both the public and private sectors, one significant gap becomes apparent when you step back: we allocate R&D money to some societal problems but not others. Once you realize this, it’s impossible to unsee.

As a society, we invest heavily in defense R&D, we allocate a decent amount to health and new therapies, and we spend smaller amounts on energy and space. After that, the spending drops off significantly. However, if we consider the major aspects of human flourishing — food, housing, work, learning, building strong relationships with friends, family, and community — we see a discrepancy in R&D investment.

We spend very little on R&D for criminal justice, education, workforce development, and housing. Midway through the Obama administration, around 2012, I read a paper suggesting agriculture would be a significant driver of future climate emissions. When I inquired about the R&D component for agriculture in our climate strategy, people were puzzled about what that might entail. Alternate sources of protein sounded completely random back then.

The same happened with transportation R&D early in the Obama administration. How could we make roads better? What do we need to do to prepare for the emergence of automated vehicles? What does the budget look like for impactful projects in these areas?

Of course we should have R&D in these fields, but we’re significantly underinvesting in R&D for social sector aspects.

This oversight leads us to discover innovations accidentally through national security spending. For instance, the Department of Defense has been a major funder of alternative medicine to ensure the health of returning warfighters, which is a prety roundabout way to fund that research. Similarly, some of the most interesting education and workforce experiments have been funded by the DoD because we allocate almost no R&D dollars to the Departments of Education and Labor.

If you’re a funder working on mental health, the environment, or homelessness, consider the R&D component of your strategy.

If you can’t identify one, don’t dismiss it—this might indicate a huge opportunity to develop that component. Otherwise, you’re simply waiting for accidental positive outcomes rather than actively investing in shaping the future.

Our view used to be that R&D should be the third bullet point of any plan. If you can’t articulate what the R&D would entail, you’re in an even worse position—people haven’t even conceived of that component of the strategy. This blind spot leads people to treat science and technology as a sector rather than a crucial component of any problem-solving strategy.

R&D on Strategic Competition Mechanics

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about China. What are the big picture questions you’re interested in regarding how the US should compete?

Kumar Garg: Here’s my question for you, or at least the hypothesis I want you to reason out with me: If the US and China are engaging in strategic competition, to what extent should they emulate each other’s strategies? To what extent, especially on the US side, which I know more about, should we play to our advantages?

I’ll throw out a few key points:

First, talent. The US is a global magnet for talent. People, especially science and tech talent, want to move here. How much should the US lean into that?

Second, the US has deep capital markets, which have created substantial room for entrepreneurship and building emerging industries on top of our university system. How can the US leverage that?

Third, the US has been home to many platform technologies in biotech, such as mRNA and CRISPR, as well as the early computing revolution, mobile technology, and now AI. To what extent should the US frame itself as a place where platform technologies thrive? What are these platform technologies?

There’s also an interesting question regarding drones.

Finally, to what extent is the healthy relationship between research in universities, formal government research agencies, and the private sector an advantage or disadvantage for the US?

I often wonder about the IRA, which is partly treated as a set of subsidies for key industries, whether in clean tech or chips. To what extent will subsidies be a major part of the future picture versus these core US advantages?

So, what do we need to improve? What should we double down on? What should we copy?

Jordan Schneider: I’m going to approach this from a different angle. I’ve been reading a lot of Paul Kennedy recently, one of the greatest living historians. His 600-page tome, The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914, has been particularly enlightening. It’s a deep exploration of diplomatic history, culture, religion, science, and media, examining how England and Germany interacted and ultimately became enemies, leading to World War I.

This book has challenged my thinking because many dynamics in the US-China context today are scrambled when considering Germany and England. For instance, England was the dominant power and Germany the rising power, yet Germany was the scientific powerhouse. Every consequential English inventor spent time in Germany to engage with their university system.

At the same time, Germany, despite being more advanced in some ways, still aspired to English culture. Their wealthiest children were sent to Oxford and Cambridge because that represented a life of luxury.

My takeaway, echoing Paul Kennedy, is that we need to zoom out further when considering a multi-decadal national competition strategy. It’s less about specific policies like subsidies or green cards, and more about the bigger picture. If you’re the larger economic power and you’re not mismanaging the transition from economic power into military power, you’re generally in a good position.

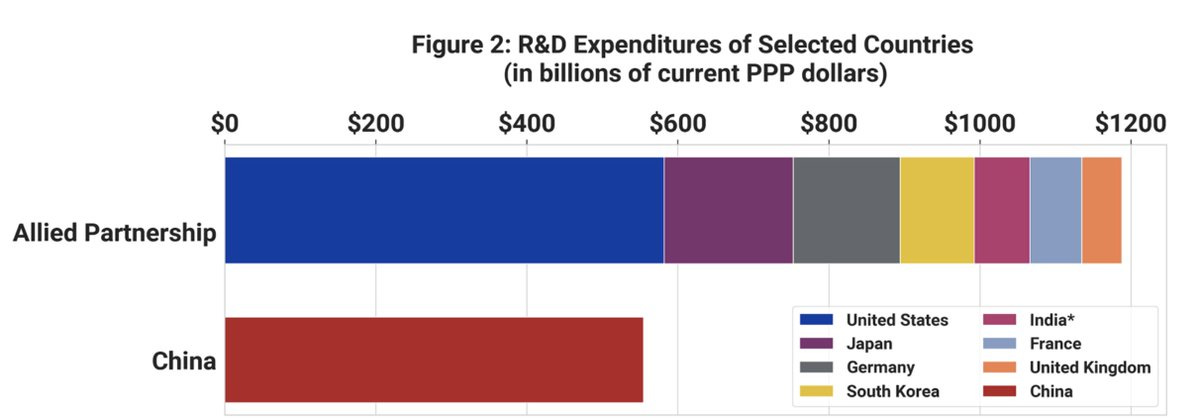

The US has a significant advantage: allies who comprise two-thirds of global GDP. If we don’t squander that, we can afford to make mistakes elsewhere and still be okay.

America’s growth, technology, and universities make us an attractive partner. There are enough repellent aspects of the CCP’s worldview and foreign policy choices that Japan, the EU, South Korea, and Taiwan probably won’t go align with China — even if the US doesn’t get everything right.

Kumar Garg: Wearing my policymaker hat, it’s clear that some of this won’t be under US control due to the two-sided dynamic. If other countries feel pushed by China, they might be drawn closer to the US. But it’s interesting to consider what US policymakers could proactively do to be better allies or to think about these longer-term trends.

Jordan Schneider: Absolutely. While we often focus on specific, tactical issues in ChinaTalk episodes, it’s important not to dismiss the broader view. If we’re risking 20% of global GDP going in a different direction, perhaps we need to increase our research tenfold to better understand what’s happening in areas like maintaining NATO and our alliance with Japan.

Kumar Garg: One reason I’ve been a huge fan of ChinaTalk is its focus on public goods — things that are valuable overall but often underfunded. While some aspects of foreign policy, like Middle East policy, are well-funded [Jordan: by Arab governments...Korea and Japan weirdly stingy both for think tankers and when it comes to influence operations and intel…], others that will matter significantly are not. We used to track this on the philanthropic side: how many people can actually speak the language and track work happening in key countries the US cares about? How much fresh analysis is happening?

My current view is that we’re moving in the wrong direction. The number of people I interact with who have active working relationships in China has been dropping for the past five years. This will impact our ability to understand how things are working.

Jordan Schneider: The structural problems you identified in the science and technology space absolutely apply to Asian studies. What I’m doing isn’t easily understood by government grants or even traditional US-China funders. There’s plenty of potential in both humanities and hard sciences, but it’s challenging to find support.

Regarding tactical advantages, the cleanest heuristic is to focus on long-term productivity and economic growth. If you can tie your initiative to that over a 10-15 year horizon and it outperforms other options, that’s the policy or donor idea to focus on.

Kumar Garg: One area where we need more activity in DC is understanding the long-term drivers of productivity. When I was in the White House, I noticed that while senior folks in the National Economic Council (NEC) and the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) recognized the importance of R&D, immigration, and commercialization for long-term productivity, often one person was responsible for all of these areas plus four others. Meanwhile, substantial resources were allocated to issues like marginal tax rate debates.

If we’re going to succeed by identifying and focusing on long-term economic growth drivers, we still have room for improvement in how we staff and prioritize these areas in government.

Jordan Schneider: It’s understandable that in a democracy, politicians focus on issues that are more immediate to voters, like marginal tax rates. However, if we’re talking about long-term competition, we need to think beyond presidential cycles. The gains from high-skilled immigration, for example, may not be immediately apparent but can lead to significant innovations. For example, Elon Musk founded Tesla in America as opposed to anywhere else in the world.

This long-term perspective makes the challenges with NSF and NIH funding so frustrating. These institutions operate on longer timescales, and we would hope they can maintain their focus on long-term goals.

Kumar Garg: Indeed, politics is about balancing the important and the urgent. Policymakers must build systems to effectively balance these competing priorities.

Renaissance Book Recommendations and ChinaTalk Parent Corner

Jordan Schneider: How does coaching your children’s entrepreneurial ideas compare to advising me and ChinaTalk?

Kumar Garg: The challenge is that in the real world, people appreciate my advice. However, for my kids, it’s like an anti-signal. If I think something is good, they assume it must be outdated. This applies to fashion advice as well. Sometimes my daughters are in the car when I’m on the phone, and afterward, they question why I said certain things. I have to remind them that they only heard one side of the conversation.

Jordan Schneider: I hear your kids are trying to start an Etsy store, and you’ve been coaching them to find a comparative advantage as creative eleven-year-olds.

Kumar Garg: They signed up for a summer camp that promised to help them make art and sell it on Etsy. On the first day, they were disappointed to learn that the camp would only help with art creation, not selling on Etsy. They proposed selling slime, but I cautioned them that it might be challenging since every kid is into slime.

Jordan Schneider: What’s their annual Etsy purchasing budget?

Kumar Garg: They spend all the money they can get — from grandparents or elsewhere — on various types and textures of slime. They spend considerable time explaining to me how each type is different. We visited the Sloomoo Institute in New York, which is essentially a slime museum. Every eleven-year-old seems to know about it. I suggested they should open one in DC, as it would be an instant pop-up success.

It’s fascinating to observe future trends through my children. They recently mentioned that all their friends are into boba tea, which I now see everywhere among young people. Fifth-graders appear to be early trendsetters.

Jordan Schneider: To close, let me tell you about my favorite Renaissance books. Lauro Martines is one of the more entertaining historians I’ve encountered. He has a three book series on political history during the Medici era. I’ve read extensive Chinese, ancient Greek, and Roman history, but Florence offers a wealth of juicy sources. There are numerous diaries and letters detailing the conniving and intrigue, including murders in churches. It’s captivating because, unlike a monarchy, Florence had competing families and factions. With the Pope nearby and the French making appearances, it’s more thrilling than Game of Thrones. Martines’ work is essentially a historical beach read.

For primary sources, I recommend The Decameron. Written during a plague year, it’s framed as a dinner party in the hills where 15 young people attempt to outdo each other with stories while fleeing the plague. It’s incredibly relatable and alive, despite being 600 years old. It’s a funny, entertaining, and at times profound piece of literature that transported me back to that era more vividly than anything else I’ve encountered. While reading Machiavelli is one thing, imagining people having fun in the Renaissance was a unique experience.

How’s this for something deeply un-antisemitic from 600 years ago!

And lastly, some 1400s Venetian parenting advice:

DoD investing in alternative medicine research doesn't fill me with confidence, that sounds more like the risks of people stepping outside of their lanes - but most of this was really positive/interesting