Xiaohongshu favorites

Contributor Yiwen Lu reports:

We have seen tons of news stories this week about Red Note (小红书). Welcome to our favorite social media, TikTok refugees! ChinaTalk has always been scavenging Red Note for gems, such as how to purchase banned NVIDIA chips.

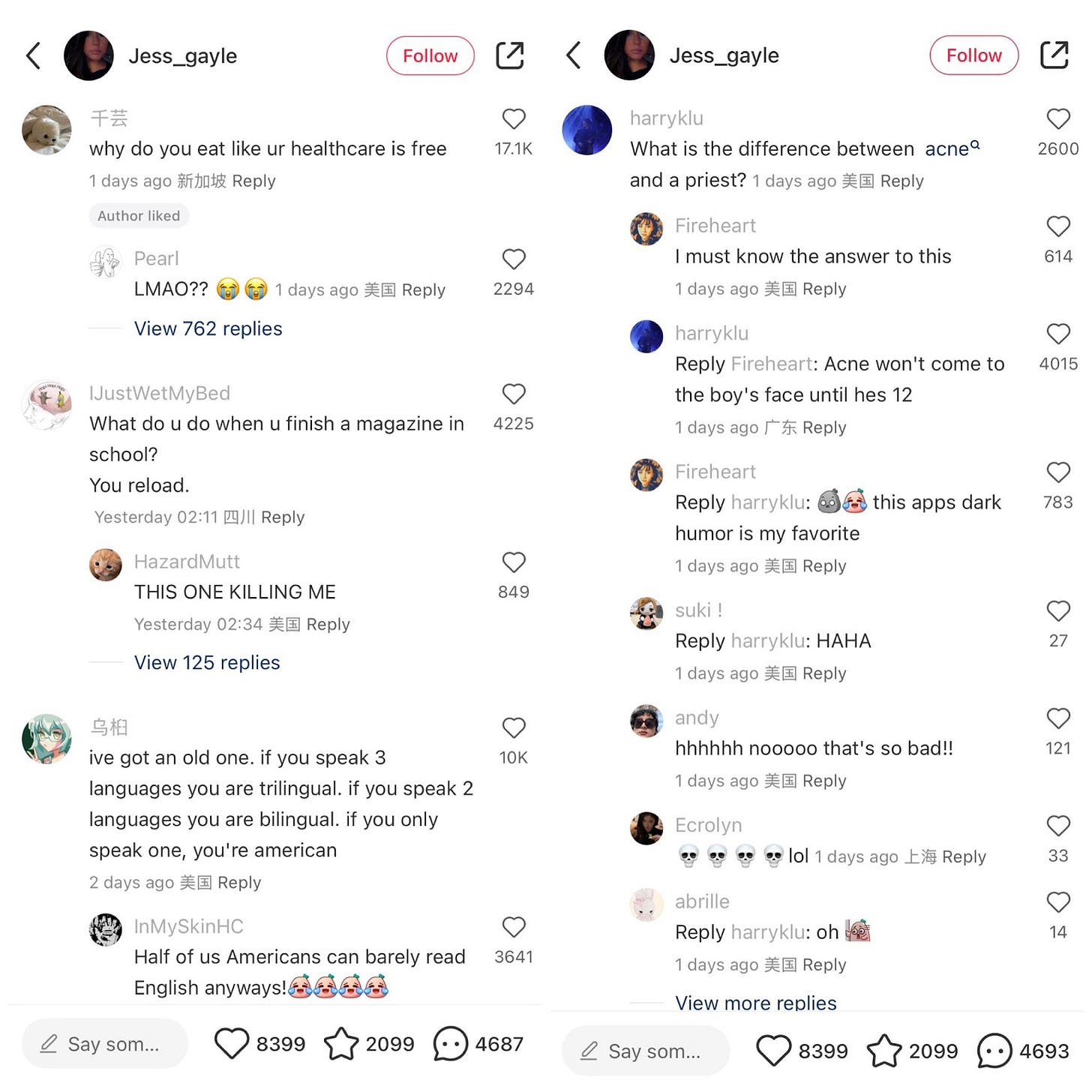

Without repeating what you have seen elsewhere, we compiled a list of the funniest interactions across our feeds.

The comment section under this post: Chinese — give us your American jokes. Please make fun of us so we can laugh.

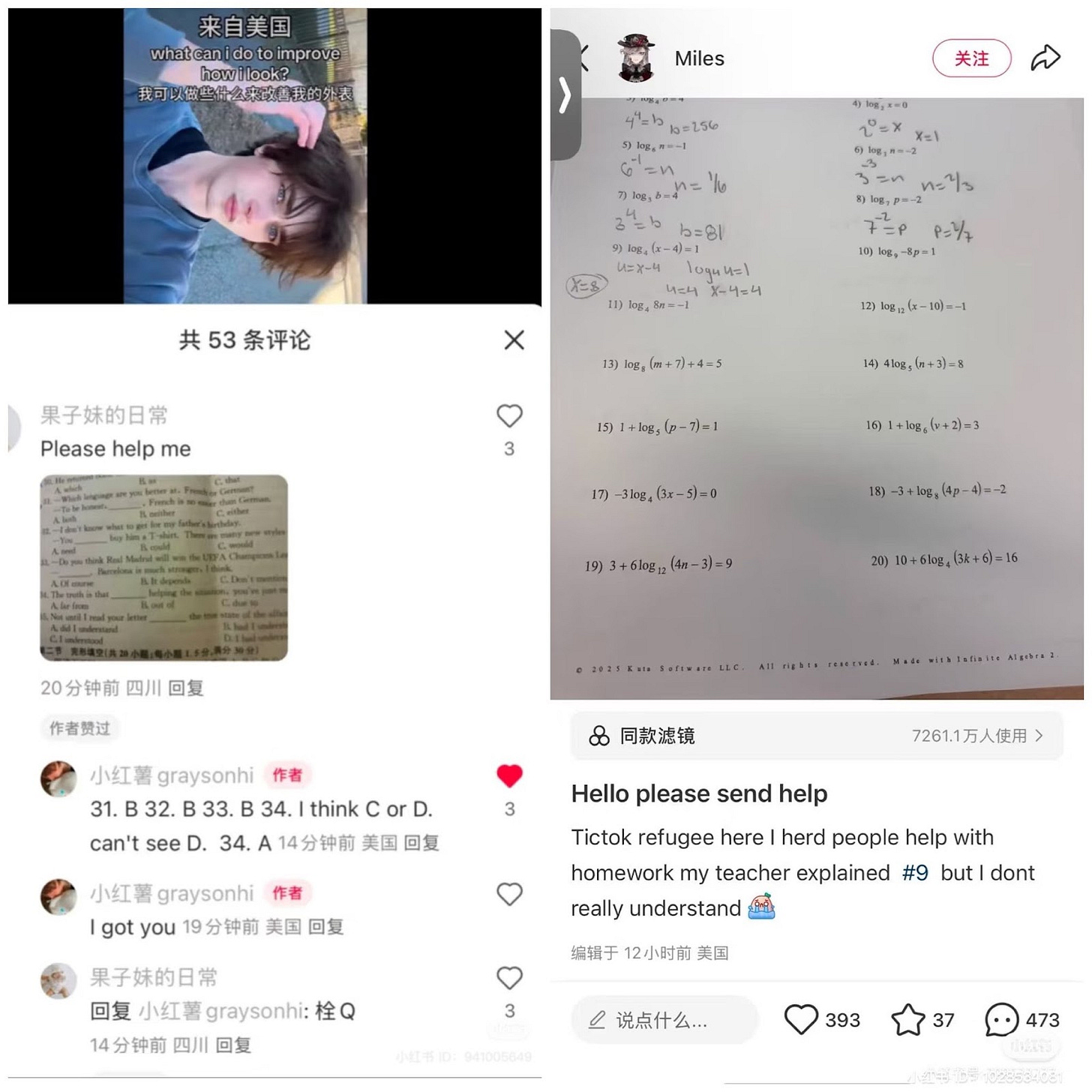

The homework exchange goes both ways.

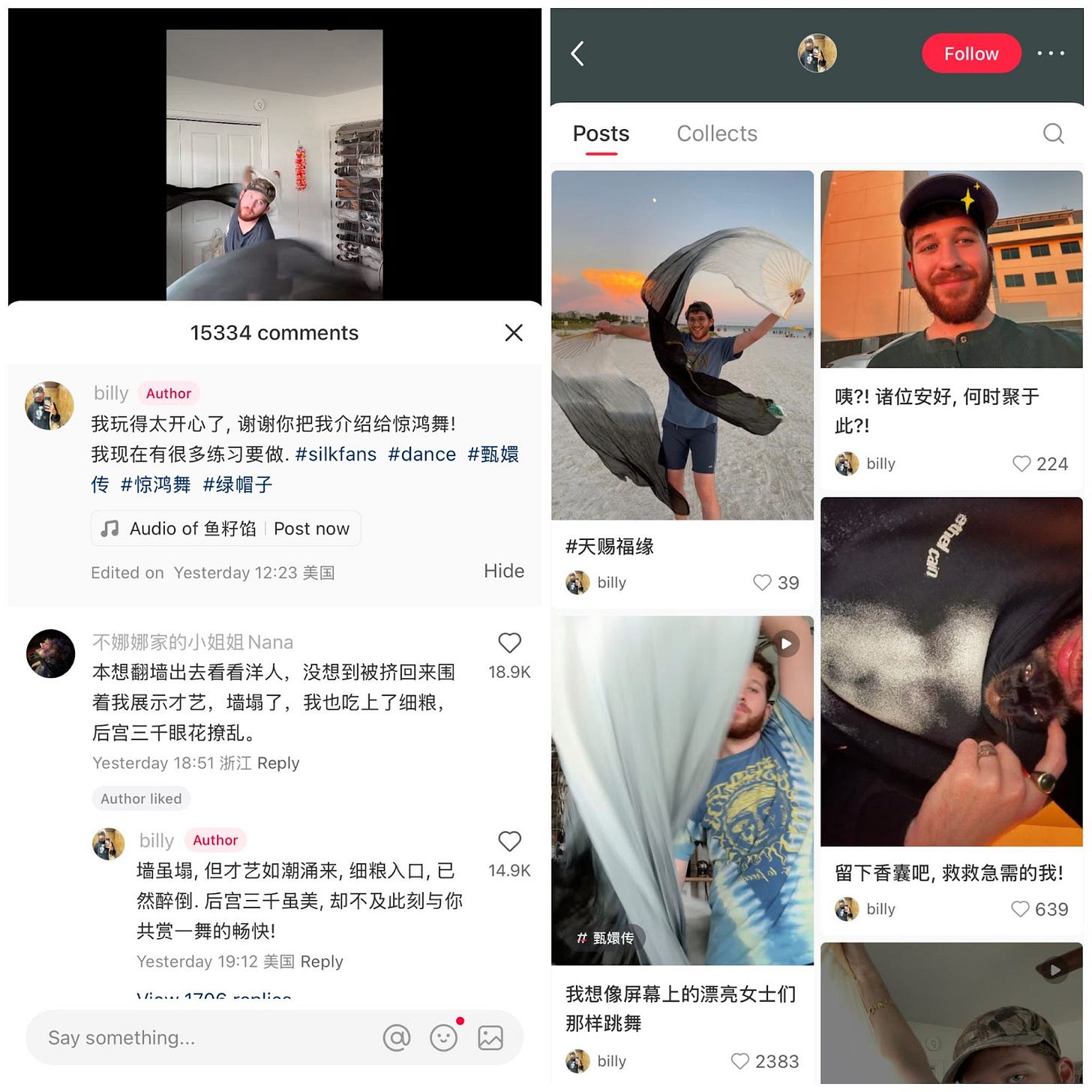

I’m obsessed with Billy from Florida, who learned about 甄嬛传 Empresses in the Palace and apparently classical Chinese as well. Here’s Billy’s Jing Hong dance, Zhen Huan’s signature dance in the show.

Jordan Schneider: fun while it lasted! I’d give it a 6/10 relative to 2021 Clubhouse moment, where you got to bear witness to incredible cross-strait discussions and minority voices from Xinjiang. See our podcast from that time on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.

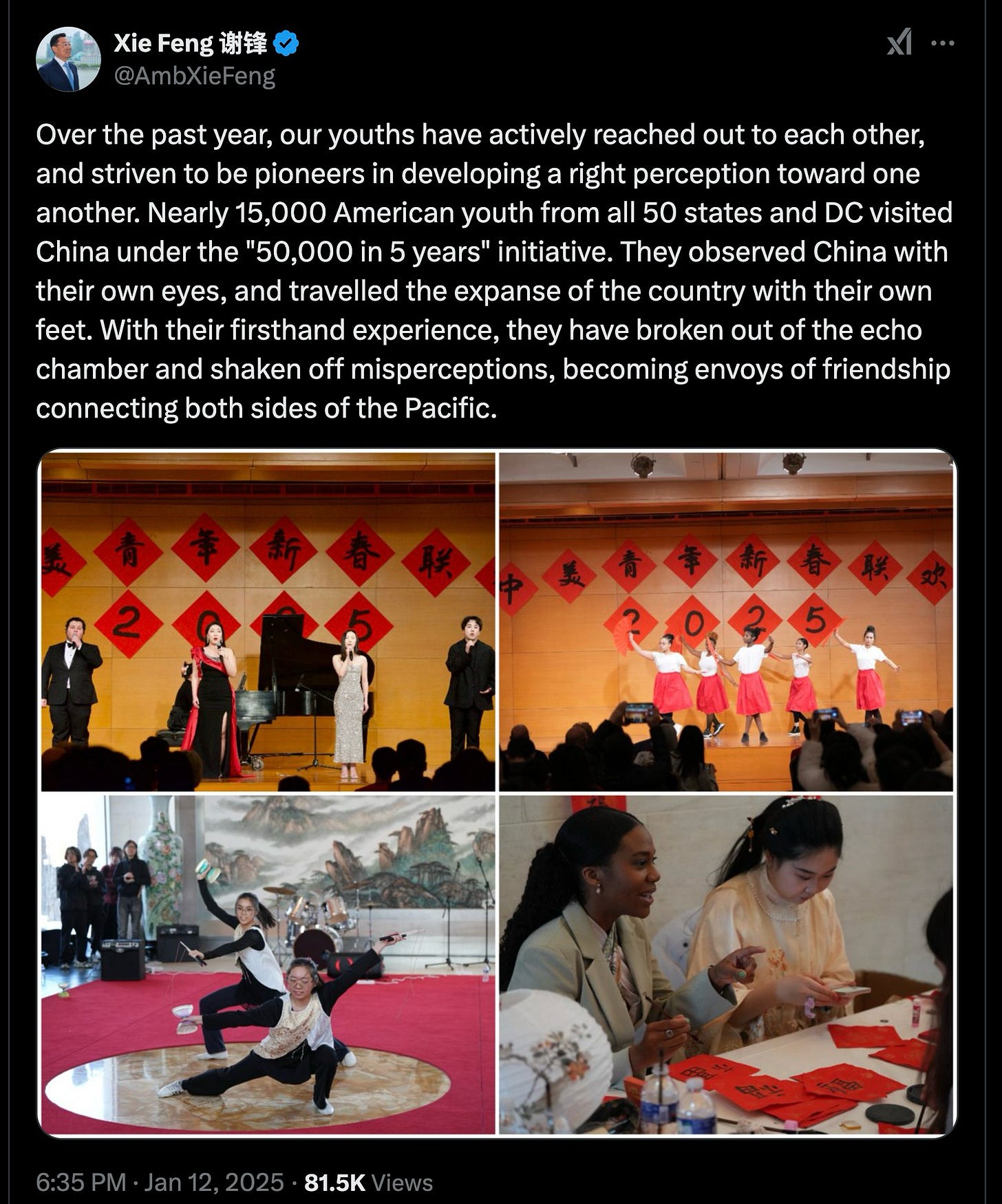

The Rednote saga is another example of the latent demand in China and the US for real people to people communication, not whatever this KPI encompasses…

…and how the Chinese government is scared of it. From The Information:

Read more of Yiwen’s XHS reflections here:

Jimmy Carter gave the US the chance to protect Taiwan while managing relations with China

Pete Millwood is Lecturer in East Asian History at the University of Melbourne. He is the author of Improbable Diplomats: How Ping-Pong Players, Musicians, and Scientists Remade US-China Relations, recently released in paperback.

Establishing diplomatic relations with China was, alongside the Camp David Accords, late President Jimmy Carter’s most substantial foreign policy achievement. As the United States pursues peer competition with China and rues what is remembered as the one-sided benefits of engagement in decades past, we might conclude that Carter should have driven a harder bargain in negotiations with Beijing before diplomatic recognition, or even that Carter was wrong to normalize relations at all. In fact, though, Carter won a critical concession from China that has helped to protect Taiwan even as the United States has an official relationship with the world’s most important post-Cold War actor outside of America.

Before 1978, Chinese leaders had told their American counterparts that diplomatic recognition would only come after the US government totally severed its relationship with Taiwan. Private trade and societal contacts could continue, but all official interactions must cease — including weapons sales. President Nixon and Henry Kissinger had gone a long way to meeting the Chinese position as early as 1971 and privately had concluded they had little chance of persuading China to accept anything more than the United States expressing its hope that China “reunify” with Taiwan peacefully.

After Carter defeated Republican Gerald Ford in the 1976 presidential election, his incoming administration asked to read the secret records of Nixon, Kissinger, and Ford’s negotiations with Mao and Zhou Enlai. Perhaps conscious of what they’d given away in early, excited visits to China, Nixon and Kissinger obfuscated. They only provided the records when Carter’s government threatened to sue. Carter was shocked by what he read. “We should not kiss-ass them the way Nixon and Kissinger did”, he concluded.

In the first summer of his term, Carter sent his Secretary of State, Cyrus Vance, to China. In part because Carter knew he’d soon have to shepherd the Panama Canal treaties through Congress, the president told Vance to put forward the maximum position on Taiwan suggested by Kissinger at the height of the Watergate crisis in 1974, asking Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping to agree to continued US governmental ties to Taiwan after diplomatic normalization, perhaps similar to the semi-official ties that the US had with the People’s Republic at the time. Carter added a further request: to allow the United States to continue to sell arms to Taiwan after recognition.

On the face of it, Vance’s suggestion was flatly turned down by Beijing. Today, when Vance’s trip is recalled at all, it is remembered as a failure. But, back in Washington, Carter’s National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski had noted what he called a “loud silence”: Deng had said nothing about arms sales. This was the first suggestion that Carter might be able to square the circle of establishing diplomatic relations with China and preserving a meaningful say over the future of Taiwan.

Like Nixon and Kissinger before him, Carter saw real benefits to a normalized relationship with China, the term used to refer to full diplomatic relations. Brzezinski was born into a Catholic family in Warsaw and his father had been a Polish diplomat posted to Moscow during Stalin’s Great Purge. Carter’s National Security Advisor was a virulent Cold Warrior and helped persuade Carter to move away from the US–Soviet détente of the Nixon era and toward renewed confrontation with Moscow. This would become transparently clear following the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, with Carter funneling weapons to the Afghan mujahideen and boycotting the 1980 Moscow Olympics. But Brzezinski’s arguments for challenging the Soviets found an earlier expression in Carter’s push for closer ties with Beijing.

One of the primary means through which closer ties were achieved was the transfer of scientific expertise and physical technology to China — including technology that had potential dual-use applications in both civilian and military sectors. As early as 1975, Deng Xiaoping had complained to Kissinger and President Ford about US export controls on the most advanced American technology. Deng said that, if US leaders wanted to move the relationship forward, they should reconsider blocks on China buying top computers. China wanted to use the computers for oil exploration, but the US government knew they could also be repurposed for conducting rocket tests and even nuclear weapons calculations. Kissinger quickly responded to Deng’s complaint, opening a new channel for circumventing the US government’s own restrictions on transfers of sensitive technology to communist states. After Ford’s election loss to Carter less than a year later, Carter continued and then deepened this policy of selling more powerful technology to China than would be transferred to other communist states including the Soviet Union — even before diplomatic normalization with Beijing.

Accelerating Chinese technological modernization helped strengthen China’s economy and military ahead of a possible future military clash with the Soviets. Seen in the context of China’s subsequent rise to economic but also military might, this triangular Cold War logic might seem short-sighted. In fact, Carter’s administration saw that more distant future coming. They knew that China saw the US as “a long-term adversary” and internally Carter’s top China advisers pledged not to “play Santa Claus”.

The United States sought reciprocity for this technology transfer in the form of normalization talks. Deng was the Chinese leader most strident in pushing for access to US expertise. Alongside his requests for physical technology, he also made Carter’s top science advisor, Frank Press, call Carter in the middle of the night to agree to receive 5,000 Chinese students as soon as possible. Carter barked back that Deng could send 100,000. Within five years, Deng had.

But Deng was, as Brzezinski had noticed after Vance’s 1977 China trip, the one leader willing and able to make compromises on normalization terms. In the final tense months of negotiations toward recognition, Deng continued to offer loud silences on whether arms sales to Taiwan could continue. The US side agreed to halt sales in 1979, the year after recognition. Other Chinese interlocutors, like Ambassador Chai Zemin who headed China’s Liaison Office in Washington, took this to mean a permanent cessation of sales. But Brzezinski had visited China in May 1978 and believed he’d got Deng to tacitly consent that weapons would continue to be sold again from 1980. After all other normalization terms had been agreed upon in December 1978, US Ambassador Leonard Woodcock met with Deng to clarify that the United States would resume arms sales. Deng said that China “cannot agree” to future sales — but he also consented to normalize regardless. In a press conference following the announcement, US officials said clearly that sales would continue.

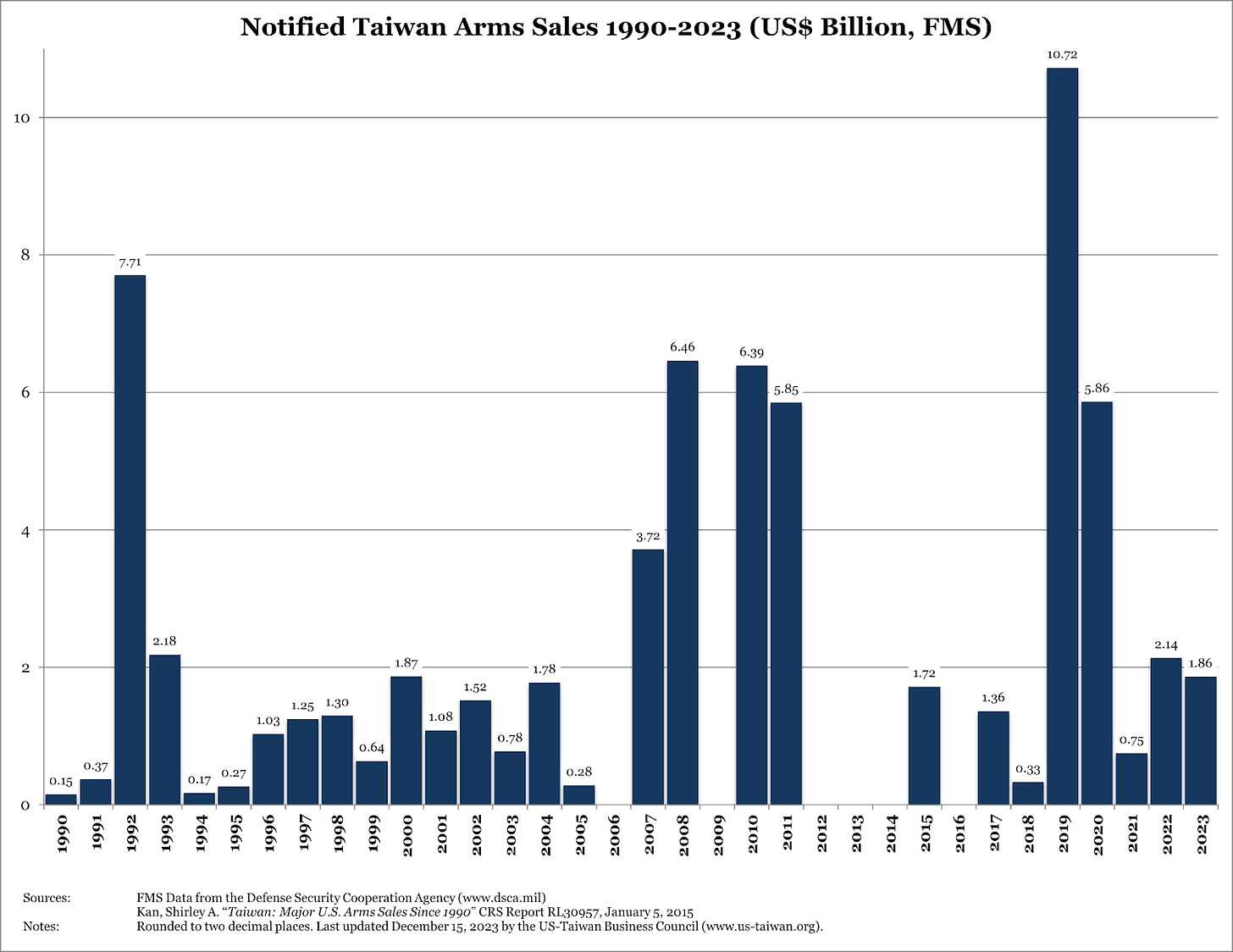

And so they have. Between 1980 and 1987, yearly US deliveries of weapons to Taiwan did not exceed $400 million. But by the mid-1990s they were worth more than a billion dollars per annum on average. Major multi-billion-dollar deals in the Obama years were followed by a further spike under Trump.

China vehemently opposes these transfers, but there has been little that Beijing has been able to do to stop the sales, even when the bilateral relationship was close in the 1980s. Deng tried to reopen the issue of arms sales after recognition. Negotiations led to the 1982 communique between the governments issued by Carter’s successor, Ronald Reagan. Reagan offered vague assurances that weapons sales to Taiwan would decrease over time — if tensions between China and the island did — but Reagan steadfastly refused to give an end date for sales.

Only now can we fully see what Deng gave away and what Carter won. Normalization was a success for Deng personally and for China. But Deng also allowed the United States a tangible means to exercise a say in Taiwan’s future, while also maintaining a relationship with China.

Some in the Nixon and Ford administrations were unconvinced that Taiwan’s continued viability was a fundamental US interest. Yes, Taiwan was a US ally — the alliance only ended after US recognition of the PRC in 1978 — but the Chiang regime had been useful primarily as a shared enemy of Communist China. Thus, the island appeared unimportant when Kissinger seemed to have made a friend of Beijing. The Chiang regime was also, in the 1970s, still brutally authoritarian, with its secret police murdering its opponents — even, in one case, outside their Californian home. Some officials might have been puzzled why Carter had worked so hard to maintain the US relationship with the island.

But then Chiang Kai-shek’s son, Chiang Ching-kuo, realized that the only hope for his regime after de-recognition was to win broad American support all over again, including for the nature of the Taiwanese government. Chiang went from Taiwan’s most feared policeman to the president who oversaw — however begrudgingly — the island’s democratization. Beijing seethed, but the 1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis showed it could not prevent Taiwanese self-rule. Carter probably did not expect Taiwan to become a democracy, even as the president who headlined human rights in his foreign policy, but his negotiations in 1978 helped to provide the space for this transformation.

US diplomats today are facing the same challenge Carter did back then: how to manage US-China relations while also preserving Taiwan’s political autonomy. Carter’s steadfast negotiating position combined with a willingness to leverage American strengths at the opportune moment laid the groundwork for a stable, normalized US-China relationship. In doing so, Carter gave Americans today the chance to find the same successful compromise he did.

Uber Eats’ Kinmen Expansion

Scooter-based food delivery is one of Taiwan’s many charms — and the industry has recently been in the spotlight thanks to Uber Eats’ attempt to acquire Food Panda, a regional competitor with better branding.

Taiwan’s government blocked the acquisition based on antitrust concerns, a move celebrated by Taiwan’s food delivery couriers’ union.

In response, Uber Eats is expanding service to residents of Kinmen, a Taiwanese island that lies 10km off the coast of China — and celebrating with pun-filled promotions. For example, coupon code 金選美食 “Kinmen-chosen gourmet food” sounds like 精選美食 “cream-of-the-crop gourmet food.”

Apart from the loss-leading discounts, the expansion might run into another problem — Kinmen is inhabited by Formosan rock macaques, a species of monkey known to attack delivery drivers and steal food. Hopefully, the union will mandate wildlife-related safety guidance for new drivers.

A college student in Kaohsiung brandishes a BB gun at monkeys attempting to steal her food:

Biden’s AI Infrastructure Order: The Right Vision with the Wrong Standards

Thomas Hochman is the Director of Infrastructure at the Foundation for American Innovation. You can read more of his writing at Green Tape.

Earlier this week, the Biden administration released its long-awaited Executive Order on Advancing United States Leadership in Artificial Intelligence Infrastructure. The order outlines an ambitious plan to build frontier AI data centers on federal land, establishing one of the most significant federal interventions in AI development to date.

The EO directs the Department of Defense and Department of Energy to each identify at least three federal sites suitable for frontier AI data centers by February of this year. These centers must be operational by the end of 2027 and be matched with clean energy generation sufficient to meet their electricity needs. Companies building these centers will be responsible for constructing both the facilities and the energy infrastructure needed to power them.

The order’s clean energy requirements will be a huge technical and economic challenge to overcome, particularly given the tight two-year timeline. There is an overwhelming consensus that powering the gigawatt-scale data centers of the near future will require a significant amount of natural gas — nuclear plants often take upwards of a decade to bring online, utility-scale battery storage for solar is still scaling up, and promising technologies like multi-gigawatt geothermal remain years away from widespread deployment.

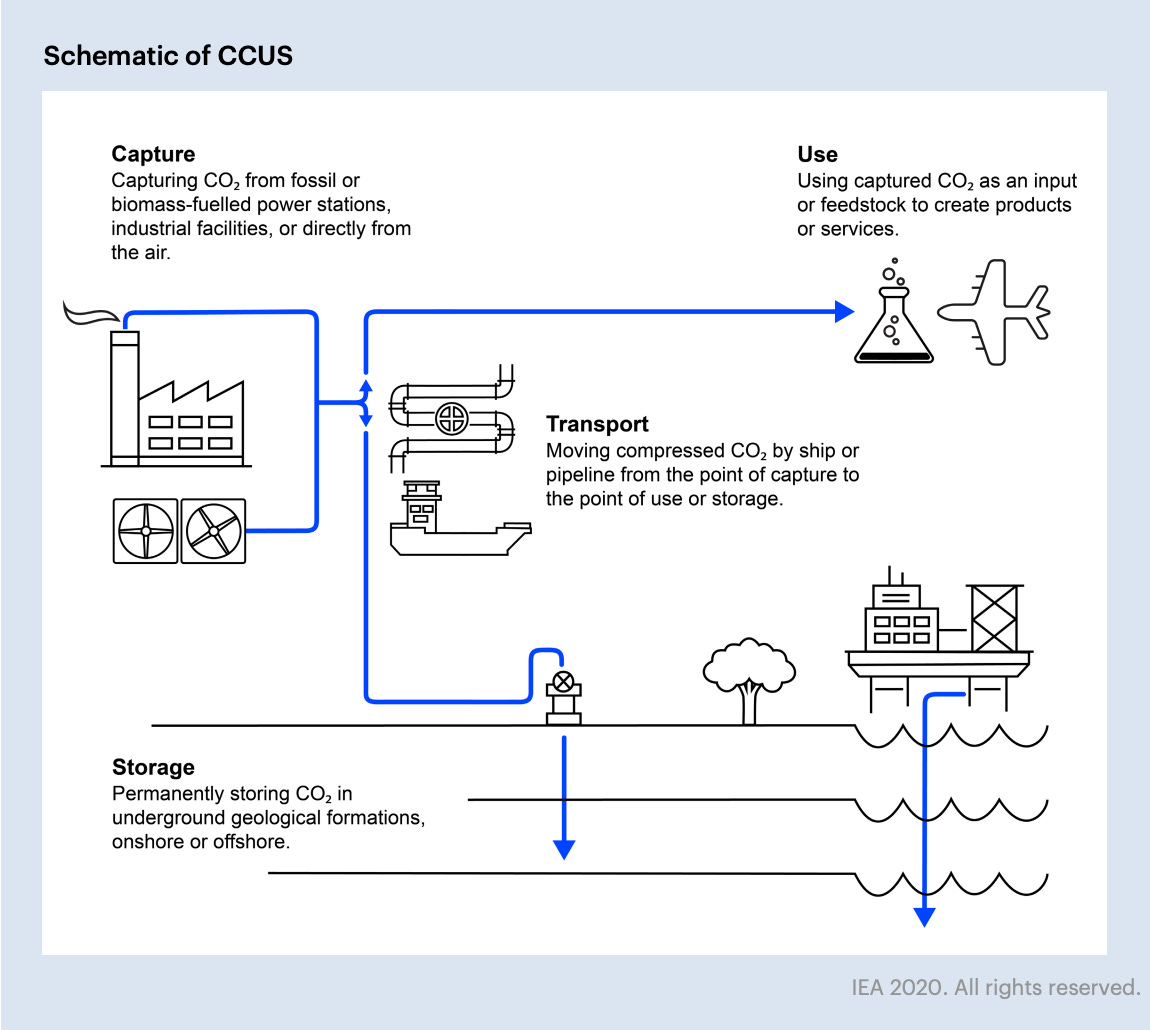

The EO does allow for fossil fuel (i.e. gas) generation… if and only if it’s paired with carbon capture technology.

Taking this path won’t be simple in practice — the order states that any fossil fuel generation must achieve annual carbon dioxide capture rates of 90% or higher, a standard that has never been achieved at scale.

While 90% capture is technically possible, there’s no precedent for maintaining such high capture rates at megawatt scale for extended periods. Folks in the industry have told me that, for megawatt-scale, post-combustion natural gas, no entity has ever achieved a full month of 90% capture rates, let alone several years. While recent incentives like the expanded 45Q tax credit will help promote carbon capture innovation, it seems unlikely that massive breakthroughs will occur so rapidly.

But all of these restrictions could soon become moot — the incoming Trump administration will likely eliminate the order’s clean energy requirements while maintaining its other provisions, allowing these frontier facilities a realistic path to move forward. If the goal is actually to advance U.S. leadership in AI infrastructure as the executive order’s title suggests, this would be a very good thing.

The executive order proclaims that all permits and approvals required for construction should be issued by the end of 2025 and also directs the Department of Defense to conduct a programmatic environmental review of AI data center effects before the site solicitation process closes in June. Both of these timelines are extraordinarily ambitious, and the order doesn’t provide much authority to meet them beyond some hand-waving at “agency coordination” and “permit prioritization.”

As I’ve written, permitting a Manhattan Project-style AI push will require leveraging every statutory exemption and workaround we can possibly find. To this end, the Department of Defense has exemption authorities at its disposal that could become critical vectors of progress. The DoD can invoke Section 7(j) of the Endangered Species Act to avoid consultation for projects deemed necessary for national security. NEPA’s “alternative arrangements” provision allows agencies to bypass standard NEPA procedures in emergencies, including in national security contexts, and 40 C.F.R. § 1507.3(d) allows agencies to make the details of their NEPA documents confidential, effectively making it impossible to sue.

Additional tools become available in the case of a whole-of-government push. These include presidential exemptions for both the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act requirements when projects serve the “paramount interest of the United States.”

If you put all of these together, you can imagine a scenario where the government can effectively transcend every major permitting requirement for AI energy development. While using these authorities for AI infrastructure would represent a significant expansion of their traditional scope, the EO seems to lay the groundwork for this possibility.

As currently written, Biden’s EO isn’t much to look at. But if and when Trump loosens its clean energy requirements, the order could provide the foundation for a national AI infrastructure strategy that keeps pace with the underlying technology.