Reflections from NeurIPS, The World’s Premier AI Conference

Plus: AI-Generated PRC YouTube Propaganda!

I spent this week in New Orleans at NeurIPS. Having spent most of the past two years engaging with policy questions downstream of AI advancements, I wanted to get a feel for those doing the real work in the field. Some reflections:

The Scene

NeurIPS was global. While most attendees sported American academic or industry affiliations, perhaps less than a quarter of the crowd had native English. My guess is at least 30% of the conference spoke fluent Chinese, with that group evenly split between Chinese and American affiliations. The rest were European or South Asian, with what felt like literal single-digit cohorts of Black and Hispanic researchers. The median age was around 28, reflecting how much new talent has come into the field in recent years. There was perhaps an 80/20 gender split. Leading lights like Jeff Dean and Yoshua Bengio spent some time just standing around chatting with whoever.

When attending Semicon, I wrote,

There’s something beautiful about how international the exhibition floor was. It’s one thing to read report after report with charts that show how global an industry it is; it’s quite another to walk the floor and see firms from across the world, most of whom play irreplaceable roles in fabrication and packaging. In the early decades, the United States was a completely “self-reliant indigenous innovator.” The progress we’ve seen since the 1980s, however, would not have been possible without the rest of the world’s work on advancing microelectronics.

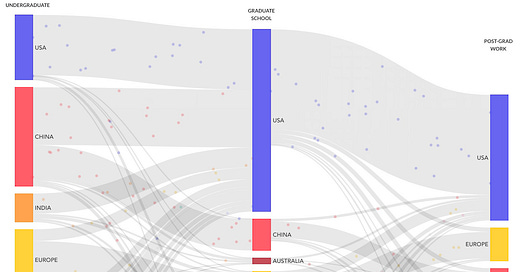

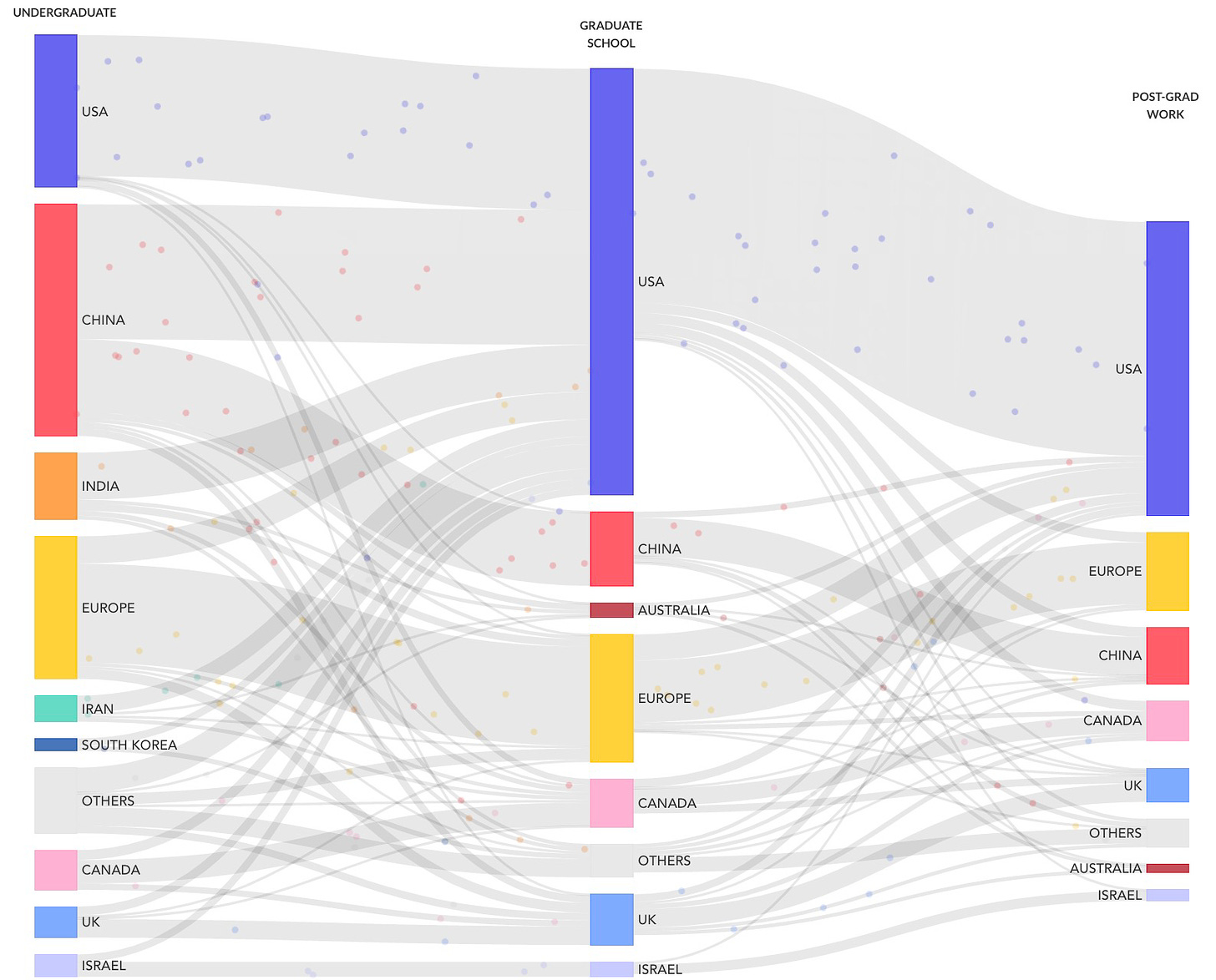

The same holds true for AI research. Immigrants to the US and researchers outside the states drive the research. It was a privilege to get to watch team after global team — many of them collaborations between the US and China — explain their posters. NeurIPS embodied a cosmopolitan vision of open science that has helped drive some of humanity’s greatest scientific accomplishments to date. Attending brought to life Macropolo’s AI Talent Tracker, which charted the career trajectories of researchers whose papers were accepted at NeurIPS 2019.

Here on ChinaTalk, we mainly cover all the forces driving China’s S&T ecosystem apart from the rest of the planet. While I believe many of those drivers are real and merit a policy response, decisionmakers in China and the G7 should understand that we are likely all to lose something profoundly beneficial for technological progress in breaking up these research communities that have flourished since the height of the Cold War.

Open vs. Closed Source — a Vibe Check

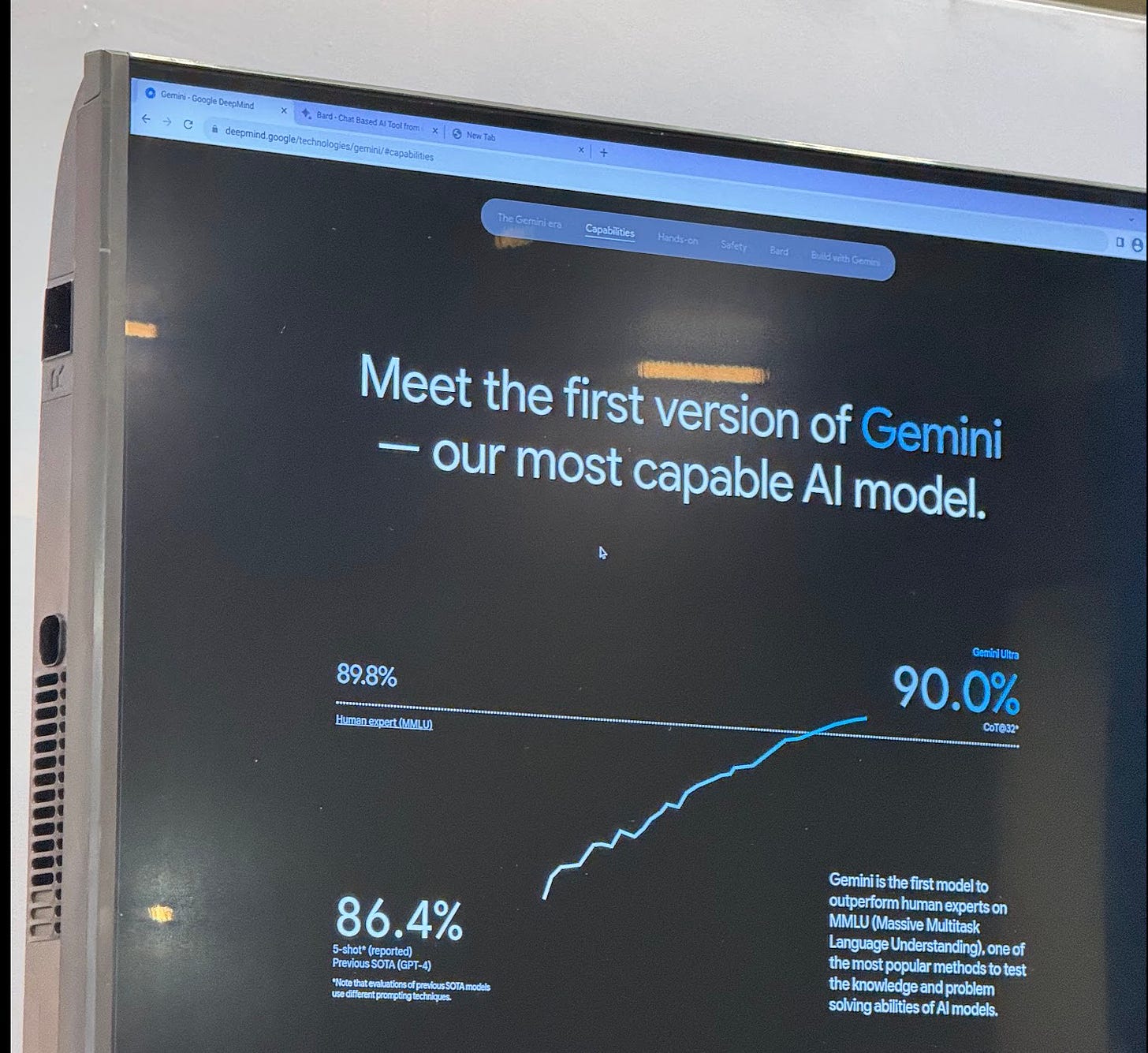

Google’s booth prominently featured the Cot@32 chart that last week made them a laughingstock on Twitter.

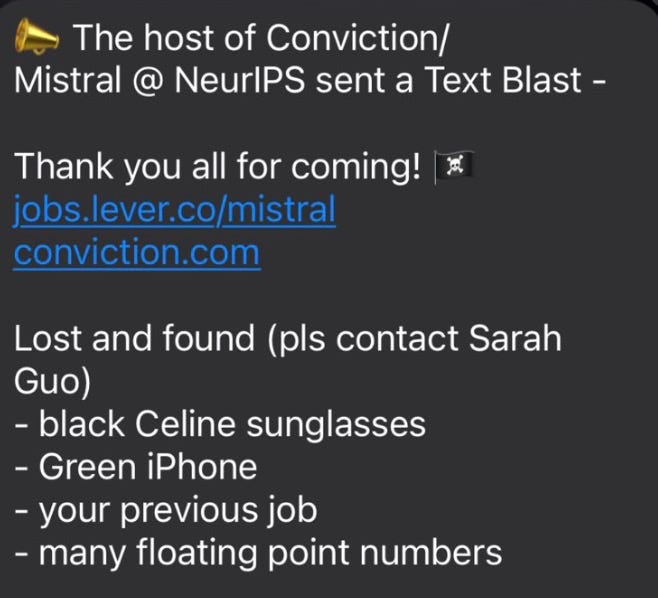

On Wednesday night, OpenAI threw an invite-only reception at some small restaurant. Meanwhile, Mistral — a French firm famous for dropping a GPT-3.5-level open-source model via a torrent link — threw a frat party complete with Bud Light, Doritos, and pizza. No one at the door took names.

Here was their text the next day:

Some interaction between talent, capital, and GPU access will define which firms lead on AI and whether a closed or more open-source vision of the technology prevails. While OpenAI and Google are the two closest to GPU Rich status, enabling the talent they attract to work on the bleeding edge, the vibes in open land are something to behold. And at least for this generation of tech, firms like Mistral are proving you can fast-follow on the cheap.

On both sides of the divide, hype is real, with people feeling overwhelmed and excited by the pace of change. As Daniel Gross recently put it in Stratechery,

I always think in all these technological revolutions, there’s always the question of, “Why didn’t it happen in 2017 or 2018?” There was no material science breakthrough that enabled this suddenly; it was not LK-99. It’s just that for every moment in history — and maybe there are some eras where there’s more and some eras where there’s less — the floor is just flooded with gold, and you’re waiting for the team to notice and pick it up and take the bet on it.

It’s Okay to Specialize

In the weeks before NeurIPS, I blocked off time to try to digest some foundational and trending ML research. It’s important for policy analysts to meet researchers halfway — but after NeurIPS, I feel less guilty for living one or two layers of abstraction from cutting-edge research. Even someone with an ML PhD can only really grok 10% of what’s happening in the field. It’s an art for tech policy analysts to find the right personal mix of following research advances, market dynamics, political developments, and historical reading to provide a unique and useful perspective on technological change. Overall, there’s a necessary division of labor so that tech policy analysts won’t end up with the best takes on whether Mamba is the real deal.

This argument runs the other way as well. It’s hard enough for these researchers to push the frontier of their fields. The Hintons and LeCuns of the world have spent their lives in computer science, not thinking about how society can and should respond to technological change. As Tyler Cowen has recently argued, “true expertise on the broader implications of AI does not lie with the AI experts themselves.” Just as after cosplaying as an ML researcher this month I hope no one is taking my ML-qua-ML takes too seriously, folks should properly discount whatever ML leading lights tweet out about regulation and policy.

Paid Sub T-Shirt Promo, This Week Only

If you sign up for an annual subscription to ChinaTalk this week, you’ll get our first-ever T-shirt!

China’s AI-Generated YouTube Propaganda

From ChinaTalk editor Irene Zhang.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) released a new report on Thursday about a network of YouTube channels producing AI-generated video essays on US-China tech with a clear pro-Beijing bent. Researcher Jacinta Keast notes that this campaign appears particularly sophisticated, presenting “detailed arguments on technology topics including semiconductors, rare earths, electric vehicles and infrastructure projects.” What makes this network stand out is also the fact that it may have attracted large, genuine audiences in the hundreds of thousands; Keast observes that the “substantial number of views and subscribers suggest that the campaign is one of the most successful influence operations related to China ever witnessed on social media.”

The aesthetics of these AI-generated thumbnails are glorious:

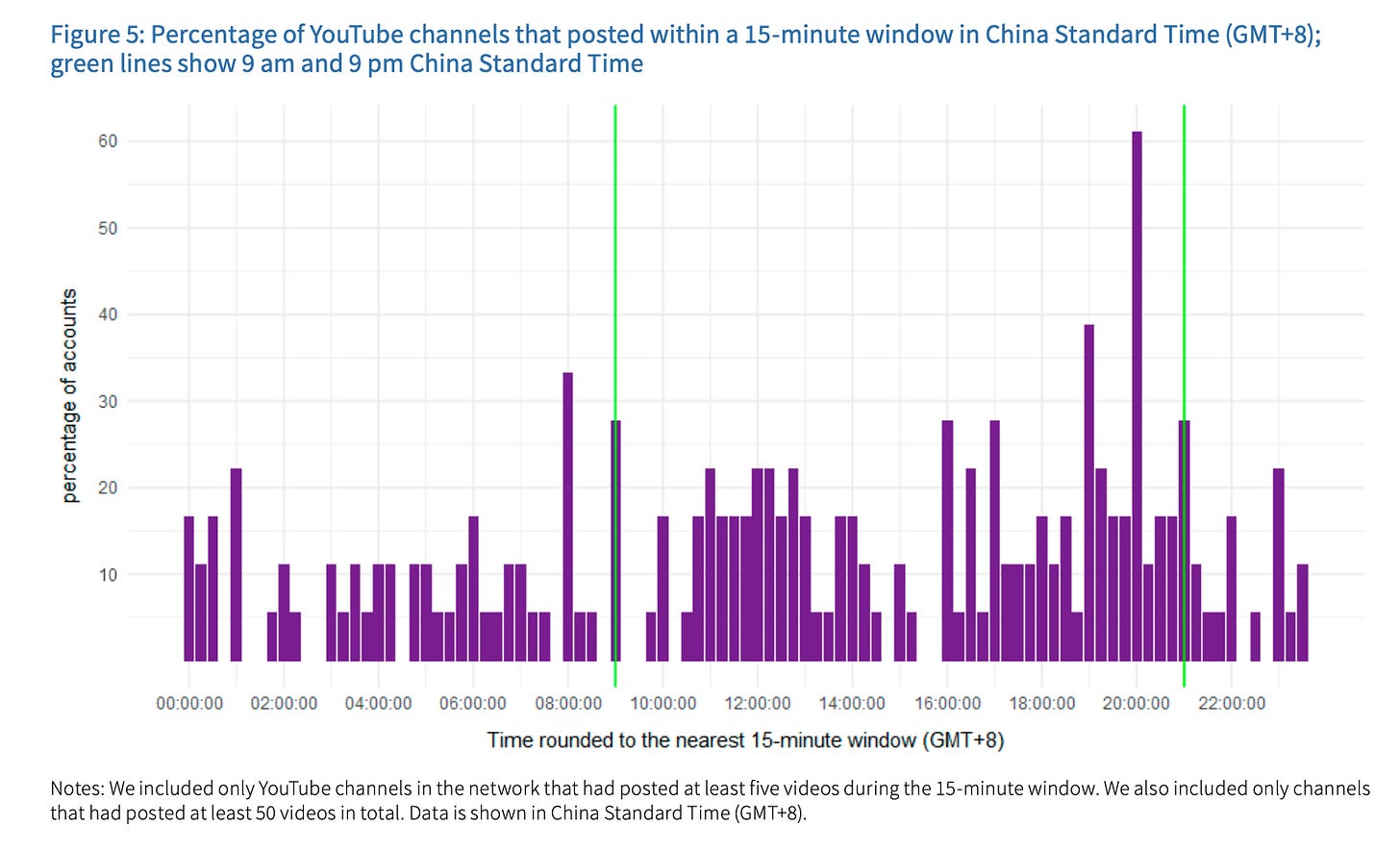

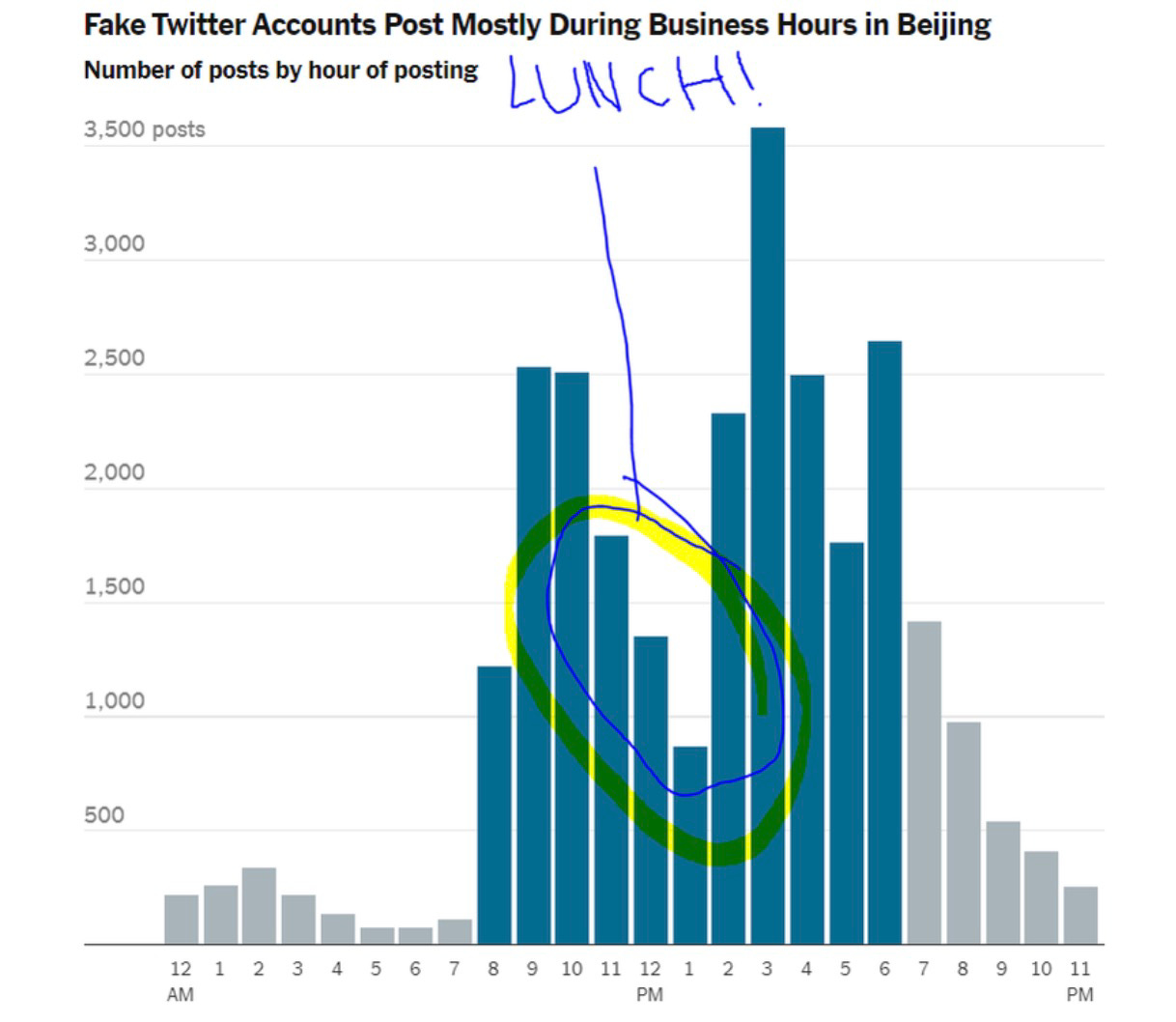

While they post content frequently, they still take regular lunch breaks, just like Jordan found in his analysis of Chinese Twitter influence networks from 2020.

From Jordan’s 2020 report:

Keast’s research shows that these channels’ voiceovers are created with generative AI. She identifies at least two channels explicitly trying to pass these voiceovers off as genuine human recordings. These videos are pretty scarily human-sounding: had I not known that the voiceovers are AI-generated, I would probably not have suspected them of inauthenticity. (The video descriptions are still pretty bad, though.)

Keast says the network pushes six main narratives:

1. China and Russia are responsible, capable players in geopolitics and current world events.

2. China is winning the US–China tech war and overcoming US sanctions.

3. China is highly capable and trusted to build massive infrastructure projects.

4. China is winning the rare earths, critical minerals and electric vehicles competition.

5. The US economy is weak, and the US dollar is no longer the world’s strongest currency.

6. The US is headed for collapse, and its alliance partnerships are fracturing.

It’s an important reminder that the era of AI-generated propaganda is already here. Subscribe to ChinaTalk on YouTube for independent, in-depth videos still done by real people!