Rep. Gallagher: Can a Scholar-Soldier Solve Congress?

Part 2 with the Chair of the Select Committee on China

I went down to DC to interview Representative Mike Gallagher (R-WI) to discuss his own view of the larger dysfunction in Congress, his role as Chairman of the Select Committee on China, and how his background in military, intelligence, and academia shape his approach to his work. See here for part one of our transcript, below for part two. You can also listen below or watch on YouTube.

Conceptual Complexity in Congress

Mike Gallagher: How frustrating is it for you, who speaks the language and actually knows things, to have to entertain me as a recovering Arabist now in charge of the China portfolio?

Jordan Schneider: Okay, let’s talk about that. Having talked to a lot of recovering Arabists who are trying to say something about China, you actually have enough humility and have done enough of the homework. I mean, come on, you’ve got The Organizational Weapon on your keg over there [a dense book on Leninism from the 1950s recommended on ChinaTalk by Stephen Kotkin].

Mike Gallagher: I do like to read. But that book was too hard for me…

Jordan Schneider: But there don’t seem to be that many of you who do! Is the scholar-soldier thing a rare breed, or do very few of them seem to end up in Congress? Am I missing them? Are they out there and they’re just all in hiding?

Mike Gallagher: I think my path was pretty circuitous, and I’m not trying to be like, “Oh, shucks, Mr. Smith goes to Washington,” as if I stumbled into Congress. I’m driven in a lot of ways. But I think it’s fair to say that — at least for the first decade of my career in the Marine Corps, and then using my GI Bill to get my PhD and working on the Hill as a staffer — I was not pursuing a political career. And to the extent I was trying to shape a political career, it was to have the warrior-scholar model in mind.

I had a lot of great mentors like HR McMaster and David Petraeus, who exemplified that. I would not have pursued my PhD were it not for them. And though I’m not advocating that one should waste time and money on a PhD, I do think it forced me to think through this stuff in a more deliberate way.

Jordan Schneider: So in your thesis, you brought up this idea…

Mike Gallagher: Not even my dissertation committee read the thesis!

Jordan Schneider: (This is my job. This is what you guys all pay me for…) You brought up this idea of conceptual complexity in your thesis: you applied it mostly to presidents, and that’s how it’s done in the literature. But I think you can absolutely do the same thing for legislators. And it seems to me that you’re probably pretty far on one side of the spectrum, in the way you characterize the incentives of the machine that spits out senators and congresspeople, which brings in folks who are more on the other side of the spectrum, or at least incentivizes them to portray themselves that way.

Mike Gallagher:

But if I remember the literature, it’s important to recognize that conceptual complexity is not a measure of smart versus dumb. It’s hedgehog versus fox; you see the world in shades of gray, versus black and white.

It’s actually useful in a lot of high-pressure situations to be conceptually simple, or to have a heuristic that allows you to deal with the complexity. Otherwise, you’re completely paralyzed.

Jordan Schneider: I guess my idea is: sure, if you’re a president and there’s a crisis, you’ve got to bomb or not bomb — you want that simplicity.

But if you’re a congressperson and your job is to negotiate and find a middle ground and trade off this and that thing, it seems as though you’d really want people who are pretty far on the other side. I don’t see a lot of them, at least on my television.

Mike Gallagher: I think what gets you on television is not going out there and being like, “You know, it’s really complicated and there are a bunch of different shades of gray in this problem.” What gets you on television is being very bombastic and forceful, offering a black-and-white view of the world.

So I think the incentives are misaligned in that way. That being said, I will say that when I first came to Congress seven years ago now, I thought the problem was the people — people that were dumb or corrupt or careerist. And of course, there are those people. But I think it has always been that way.

There are a lot of very talented people too. There are a lot of very smart people. To bring it back to our initial point: I think the problem is when good people meet bad process and they get disillusioned, or they then change their way of operating to respond to rational incentives.

If you’re getting rewarded for being black-and-white and not offering any nuance at all, then I think that you’re going to see more of that behavior.

Jordan Schneider: So how do you fix that?

Mike Gallagher: The committee reorganization I talked about before. I think there are a lot of little things. What were the three things I offered in my Atlantic piece? One was the committee reorganization: fixing the divide between authorizing and appropriations.

The other was just changing the schedule. The schedule makes absolutely no sense here. Our work schedule is crazy. A bunch of little tweaks like fixing the calendar and then aligning the fiscal year with the regular year could make this a more productive place to work.

I suspect there are probably some political reforms that influence how people get here in the first place that you would need, some sort of grand bargain on term limits for some campaign finance thing: whether it’s that you can donate only to someone you can vote for or you can’t campaign while Congress is in session. To me that makes sense as well.

Learning from Intel vs Archives

Jordan Schneider: Learning about how the world works as an intelligence officer versus spending time in the archives: what can each one of those teach you that the other can’t?

Mike Gallagher:

What [intelligence and academic research] have in common is that both impress upon you how valuable it is to be able to write well, and quickly. To be able to express your thoughts in simple and direct prose is a valuable skill whether or not you want to be a policymaker, or even work at a tech company.

I think that’s an increasingly rare commodity. I’m not saying I’m a great writer, but I think if there’s anything I’ve done well — and a shoutout to a great China hand, Oriana Mastro, who taught me this — she had this concept of sacred writing time, where she would get up super early and just write for an hour and block out everything else. And when I was struggling to finish my dissertation because I was working full time, that was the only thing that allowed me to make progress.

I’d wake up at 4:15, and then from 4:30 to 5:30 I had that Freedom app on my computer that blocks all Internet, and I’d just write for an hour. So writing is important, at least in how I think through the world.

In terms of differences between being an intel officer and a struggling wannabe academic in Abilene, Kansas, living out of the Holiday Inn Express? I’ve never thought about that before. I was a human intelligence guy, right? So, as we used to say, the problem with humans is that it involves humans, and you’re having to make a judgment call on the reliability of the source in front of you, whether it’s a detainee that you’re interrogating or a source you’ve cultivated over the course of many months. That might actually be easier than having to make an assessment of the reliability of someone you’ve never met whose notes you’re reading, or whose marginalia is scribbled in whatever file in Abilene.

But in either case, it involves a judgment call. It’s an area-fire weapon. It’s not a precision-guided munition, as it were.

Jordan Schneider: What have you taken from those two roles? What mental models have been injected by dealing with Iraqi detainees versus trying to figure out what the hell Eisenhower was thinking after Project Solarium?

Mike Gallagher: I had this formative experience in Iraq where we were looking for this bad guy for a while, and the previous unit had been looking for this bad guy for a while, and we thought we knew exactly where he was on various occasions and couldn’t find him.

And it turns out that we, through a source of ours, were able to find him hiding inside of a couch, which to me was this lesson: even at the tip of the spear in an area where we felt like we knew everything that was going on and we didn’t have to worry about these big geopolitical problems — it was all about the tribal politics of the Mahalawi tribe versus the Karbuli tribe and things like that; it still was very messy, and the fog of war was very high. So I think it gave me a basic sense of humility.

I try to apply what I call the Lance Corporal test now: as we’re making these big decisions in DC, I try to think through — when it’s translated to the tip of the spear — the complexities and the unintended consequences.

Mental models from Eisenhower: I do think a basic respect for the decisionmaking process, which Eisenhower was exceptional at. He attended almost every single National Security Council discussion.

The Solarium exercise, which I wrote a chapter on, is famous now for how deliberate and rigorous it was, and for [Eisenhower’s] ability to force debate and productive dissent.

I’ve also taken a basic appreciation for prioritization and how necessary it is at the level of grand strategy. If you read Eisenhower, there’s this constant tension between the investments necessary to defend the American way of life — and he thought about it very much as a way of life and a spiritual thing as much as it was a physical territory — and what that would do to America over the long term, whether it would fundamentally alter America because of those investments and because of the demands of the Cold War.

Beyond that, I don’t know. Maybe unconsciously, I have all these mental models. I do think — and I try to be honest about this — because I’ve spent so much time thinking about the late 1940s and 50s, there’s a tendency for me to see parallels in the present day. I try not to overstate that.

I know people argue over this phrasing of whether we’re in a “new Cold War.” But I find the analogy useful both for the similarities it illustrates, as well as the differences it illustrates. And they’re obviously very real differences: Communist China is not Soviet Russia.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on Eisenhower for another second. So when he set up the Solarium, he bounded what could be debated and said, “These are the facts, and we’re going to engage with them and go from there.” And I think something that is very broken about America — which maybe was slightly less broken in the 40s and 50s — was the appreciation of facts as they were. Then you could have a debate about a tighter range of more relevant things than “is the sky blue.”

Thoughts on how that maybe does or doesn’t apply today?

Mike Gallagher: I take your point. One thing I said — particularly in some of the brutal debates we’ve had over the last election and some of the more divisive things politically in recent years — is that it’s not even as though we’re having an ideological debate.

We’re having an epistemological debate about what’s true and what isn’t. And obviously, I think that’s related to the fracturing of the media.

In Eisenhower’s day, there were only a few sources of information. I think most people trusted one of the two newspapers that were available or one of the four channels that were available. No such situation exists right now.

Jordan Schneider: The thing is: people were very wrong then, too. People thought Stalin was great. People thought Mao was doing a good job. So you could all agree about something and still be really wrong.

Mike Gallagher: Totally. No one conceived in 1950 that the North Koreans would invade the South or that China would then become involved later on.

There are definite tradeoffs, which is why people should just opt into the ChinaTalk view of the world and only get their information from your podcast and your Substack! And then we can all agree on the bounds of the debate. There is, however, this debate that persists today about whether Eisenhower rigged the game: whether he went into the exercise basically already having decided on a version of what was Task Force A under George Kennedy’s — a great Wisconsinite — leadership, sprinkling a little bit of B and C on top of it, but [having] rigged the game in favor of his preferred strategy.

And I think that’s a conclusion reached most notably by Richard Emmerman, who with Robert Bowie, wrote Waging Peace: How Eisenhower Forged an Enduring Cold War Strategy, and a classic article called Confessions of an Eisenhower Revisionist: An Agonizing Reappraisal. I slightly disagree with it, but the debate rages on.

Defining the China Debate

Jordan Schneider: That is the critique that some would give you and many of your colleagues: look, the bounds in which you’re willing to interrogate versus not interrogate are more narrow than they should be.

Mike Gallagher: I think there’s a shared bipartisan recognition that the CCP … well, actually, no, there’s not even a recognition that the CCP is our greatest threat. I think there’s a meaningful number of Democrats who would say climate change is our greatest threat. Someone attacked us for being too bipartisan and groupthink, a bunch of prominent people have. But there are a lot of meaningful disagreements happening on the committee, even within the parties.

There are dramatically different views between me and members of the Financial Services Committee on how to get outbound. There are different views on the overall relative prioritization of climate change, there’s obviously disagreement between me and the Biden administration on engagement and whether it’s useful right now.

Then there are debates that are more in your community — or the outside think tank community — more than they are in Congress: what exactly China’s ambition is. Is it just regional dominance? Is it global dominance? What does global dominance mean? Are they trying to reshape the system? Are they actively trying to destroy us? Are they trying to get us to commit physician-assisted suicide? This is the debate in Rush Doshi’s book [The Long Game] and Ian Easton’s book [The Final Struggle].

There’s debate over whether or not Xi Jinping is serious when he says, “I’m going to take Taiwan by force if necessary.” There’s a debate about the timing for that.

The biggest divide is between the financial community and the national security community. And in some cases, that divide is bigger than the divide between me and my ranking member on a lot of issues.

Jordan Schneider: Strategic shocks versus solarium-considered development: I think we have a horrific case study happening right now in Israel. You have had a horrific attack — and if you could press pause on time and think for three months about all the different options that you would take to deal with the problem, that would be great. But that’s not going to happen because they live in a democracy.

I could see a similar thing happening in a Trump, DeSantis, or — God forbid — Vivek 2025 administration: where a blockade happens, a bombing happens, and all of a sudden there’s going to have to be a decision point of whether or not it’s worth it to defend Taiwan. Are you worried about that? You mentioned the isolationism threat earlier. What does America need to do to think through the tradeoffs of that?

Mike Gallagher: In the more immediate term, I’m worried there are bizarre parallels to 2014 to 2015, where we had tried to extricate ourselves from the Middle East and chaos ensued, and we had the first failed pivot to the Pacific.

I think the idea of the pivot is flawed, this idea that we can neatly pick up our investment in one region of the world and focus on the Indo-Pacific. I know I’m simplifying it — I know smart people like Kurt Campbell and otherwise would reject that characterization.

But the point is: we have interests in the Middle East that we’re going to have to defend and advance, and we have interests in the Indo-Pacific — and I do think the Indo-Pacific is our priority theater. But I worry that in bizarrely similar ways, i.e., Biden comes in trying to resuscitate the lifeless corpse of the Iran Nuclear Deal, misunderstands the basic alliance structure, underestimates the lengths to which Iran would go to screw up any rapprochement between Israel and the Sunni Arab Gulf states, Saudi Arabia in particular…

Now we’re going to be dealing with regional chaos that’s going to consume so much of our time and energy that we may not put in place a deterrence by denial posture [in the Indo-Pacific] in the next three years that would make an invasion [of Taiwan] less likely.

But to the thrust of your question:

I do worry. I feel like part of my job on this committee is to make the case that defending Taiwan matters, or that helping Taiwan defend itself is aligned with our current policy. But certainly if China were to attack Taiwan, I would make the argument that we have an interest in helping repel that invasion.

Jordan Schneider: The question is: how much can you really “solarium” your way into putting the cards in the right way in the deck so that when your strategic shock comes, you end up choosing the right path.

Mike Gallagher: Well, I don’t think we need to solarium our way into it. We don’t need to have some prolonged six-month debate about the best path forward. I suspect you could lock me, Eldridge Colby, and Eli Ratner in a room, and we would come up with something.

Jordan Schneider: Because this is not a strategic surprise.

Mike Gallagher: Because this is something we know.

What we have to do is just surge the right type of hard power to the Indo-Pacific — and to the First Island Chain in particular — to make it a fundamentally unpalatable military proposition for Xi Jinping. That is the thing we must do within the next five years, before it’s too late.

Jordan Schneider: Last thing: how do you think you’ve improved in this role, and what do you want to keep working on or get better at? Or what skills do you wish you had?

Mike Gallagher: I wish I were better at speaking extemporaneously, and I keep thinking I’m going to wake up and that’s going to be a skill I have. But I have to write things out and think about them, to pretend like I know what I’m doing.

I think I’m getting a better respect for different committee jurisdictions and how you need to bring people along and you can’t just ram something down their throat. This is because of the fundamental challenge of the committee: we don’t own legislative jurisdiction, so our power comes from our ability to make the case publicly, do investigations, and then build unique coalitions. That’s something we’re still working on.

Jordan Schneider: And you as an individual — and a legislator?

Mike Gallagher: So many things. As much as I crapped on the soundbite culture and how TV rewards the black-and-white analysis, you do have to do it.

I think I’ve grudgingly accepted the fact that, in order to be successful, I have to engage on TV. Particularly whenever I can do it with my ranking member, I think it sends a powerful message. I’m naturally built as an introvert, and I’m naturally wired to just read books and write things. But getting comfortable with the external-facing part of the job is something I’ve accepted and I’m trying to get better at. I’ll leave it at that.

Jordan Schneider: Well, you’re welcome on ChinaTalk to help you practice.

Mike Gallagher: I loved this conversation. Since you referenced cognitive complexity, I have to confess that I actually think the measurement of it is totally bogus. They measure the transcripts of interviews — non-scripted answers — and they code it. Part of what I did in that dissertation is to problematize the measurement of foreign policy experience, which is easier to measure — like, Truman rates historically low, even though he led the Truman Commission, which was the reason he became vice president. So, actually, with a more accurate measurement, he becomes a higher-level-scoring president. I do think experience matters.

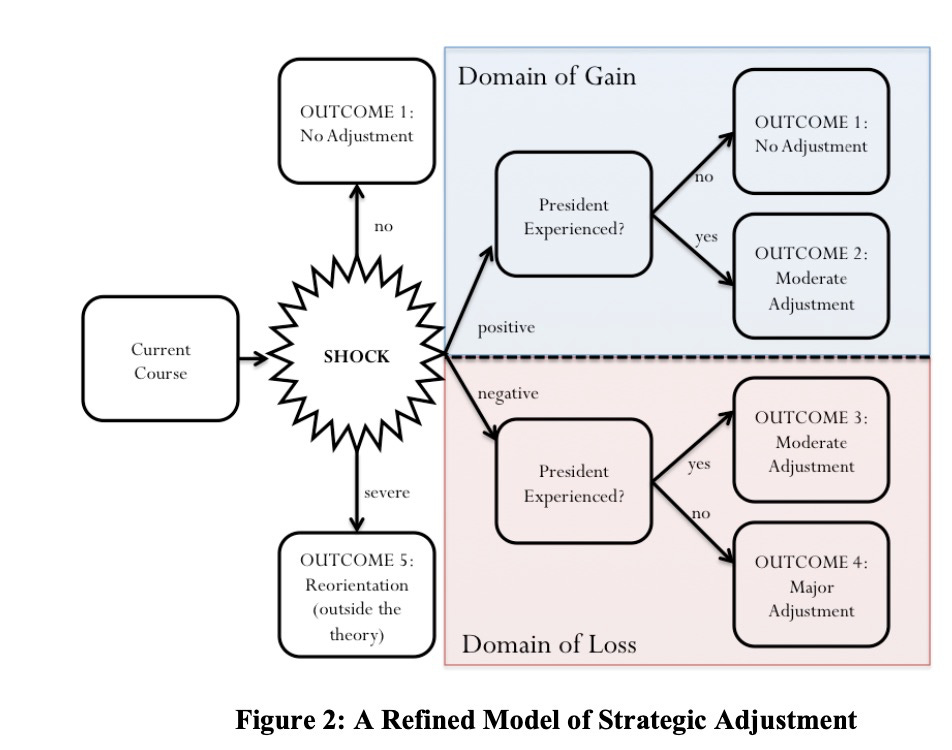

On the other hand, in the course of that, I gained a respect for prospect theory. I think prospect theory is actually useful: it helps understand decision-making in a useful way that isn’t overly simplistic.

Jordan Schneider: Well, earlier you said Selznick was too hard for you. So to balance you off, I brought you a copy of Elting Morison’s Men, Machines, and Modern Times. It’s beautifully written, exploring case studies of how bureaucracies respond to technological change.

Mike Gallagher: It’s like right up my alley. I love it.

Jordan Schneider: Rep. Gallagher, thanks so much for being a part of ChinaTalk.