Rickover’s Lessons

"The status quo has no absolute sanctity"

Charles Yang is the executive director for the Center for Industrial Strategy, a bipartisan think tank focused on industrial policy. Previously, he served as an AI and Supply Chain Policy Advisor at the Department of Energy and was an ML Engineer at an AI hardware startup in San Francisco. Today, he’s here to present some excerpts from his research into how Admiral Hyman Rickover built the nuclear navy.

Strategic competition demands more than technological innovation — it requires building industrial power. The U.S. is realizing the damage done by decades of underinvestment in the nation’s industrial base, which now jeopardizes its ability to compete on the global stage. Today, the production capacity of Chinese shipyards is over 200 times that of US shipyards, and China has used its chokehold on critical mineral processing as leverage to retaliate against US sanctions.

A new bipartisan consensus is emerging around the need for industrial policy — from the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act, to the recent bipartisan introduction of the SHIPS for America Act and the Critical Minerals for the Future Act.

As Congress steps into this more active role, policymakers should learn from the successes of our past. Nearly 75 years ago, Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, “Father of the Nuclear Navy”, pioneered a bold program to develop and operationalize nuclear power in the Navy. Under his leadership, the U.S. government harnessed the power of the atom, building the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine and the world’s largest fleet of nuclear reactors for civilian power.

Lessons From the Past

Rickover spent his entire career in the Navy and is still the longest-serving naval officer in US history. He spent the first 20 years of his career as an electrical engineer, where he honed a strong technical foundation and unique management style. In 1946, he was assigned a 1-year tour of duty at the Oak Ridge site of the Manhattan Project. Rickover immediately recognized the transformative potential of nuclear technology — he spent the rest of his career building the “Nuclear Navy,” which ensured US strategic dominance of the high seas for the rest of the 20th century.

Within the span of 10 years, Rickover created an entire office dedicated to nuclear propulsion, and successfully launched the world’s first nuclear-powered submarine without cost overruns. He conclusively demonstrated the strategic importance of nuclear propulsion in a timeframe no one thought possible and helped the US beat the Soviets to nuclear propulsion for submarines by 3 years. His institutional legacy is the US Navy’s safe construction and operation of nuclear reactors.

As the US gears up for another strategic competition, Rickover’s story can offer helpful lessons for aspiring technocrats. Oftentimes, industrial policy is framed in terms of legislation, but Rickover demonstrates that industrial policy is as much about policy as it is about strong leadership.

Talent, Training, and Management

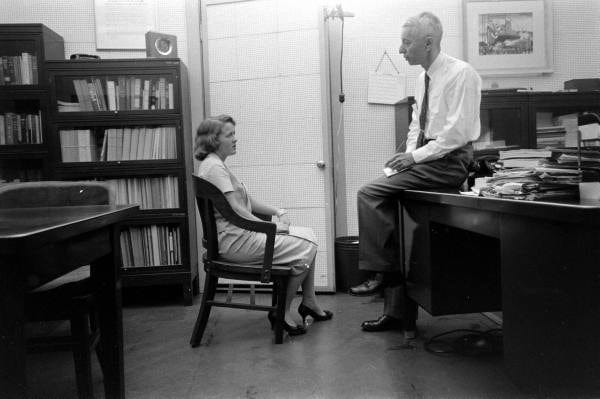

Rickover spent an inordinate amount of time focused on interviewing personnel — he made the final hiring decision for every naval officer who applied to serve on a nuclear submarine until he retired. And he was an unorthodox interviewer, screening for high agency individuals who could think on their feet — literally! To test their composure, Rickover famously made candidates sit in a chair with the front two legs shortened as he loomed over them during questioning.

One interview account:

For one interviewee who said he liked hiking, Rickover asked him if he had ever hiked the nearby “Goat Mountain”. When he said he had not, Rickover told him to bring him proof he had climbed it by tomorrow morning and he would be hired. It turns out that Goat Mountain was the peak of a structure for mountain goats in a zoo. He went to the zoo, asked a tourist to take his picture, jumped into the enclosure, and climbed to the top. He’s hired the next day!

But it didn’t end at the interview process — Rickover believed in continued technical training for his staff and in building out a talented workforce base for this new technology:

While Rickover worked to staff up quickly in the short term, he also set out to build a deep bench and a long-term pipeline of talent. He required each officer and engineer he hired to submit a self-study plan demonstrating mastery of advanced texts in metallurgy, physics, and chemistry, along with field trips to AEC facilities, totaling 854 hours of study or 16 hours per week. He also worked with MIT to develop a survey course on nuclear physics and a master's degree in nuclear engineering, with a curriculum drawn up and agreed to by Rickover, starting in June of 1949. Rickover also worked with Oak Ridge National Lab to develop a 1-year curriculum in nuclear science and technology, a program christened “Oak Ridge School of Reactor Technology (ORSORT) with the first cohort starting in March 1950. Westinghouse, GE, utilities, naval and private shipyards, and Naval Reactors all sent students to ORSORT and the program started turning out ~100 graduates a year, providing another training center to develop a nuclear industry.1 Finally, Rickover had his engineers provide training lectures to a variety of audiences, ranging from senior officials in BuShips to junior technicians, as well as to explain shipboard problems and applications to scientists at Argonne, Oak Ridge, and Westinghouse/GE.

He was also known for his unique style of management. Not only did he interview every naval officer in his office, he also maintained direct lines of communication with every nuclear sub commander and project officer on-site with contractors, giving him early awareness of every issue. The demanding oversight he extended over his technical staff under his command pushed them to have greater awareness of their own direct reports:

Rickover was also an intensely demanding and scrutinizing manager. As most writing then was done on carbon copy paper, every night Rickover would collect the “pinks” of every piece of writing from his various teams i.e. the carbon copied half, and read over them at home, including drafts. When his officers protested as to how they should be expected to keep track of everything in their purview, including drafts reports from staff below them, Rickovers responded “It’s up to you to see that I don’t know more about what’s going on in your shop than you do”. By enforcing tight lines of supervision over his officers, Rickover ensured that he maintained full visibility into each team, including the project facilities at Knolls, Bettis, and the shipyards, allowing him to catch problems early on. It also enforced a culture of direct accountability and oversight across the organization.

Rickover’s focus on hiring, training, and close project management represented his philosophical approach to how to build complex systems managed by humans.

Near the end of his career, Rickover testified to Congress after the Three Mile Island Reactor accident. He spent the vast majority of his testimony talking not about regulatory reform, but about the lack of training and inadequate culture of responsibility among the operators.

“Human experience shows that people, not organizations or management systems, get things done. For this reason, subordinates must be given authority and responsibility early in their careers…

Complex jobs cannot be accomplished effectively with transients. A manager must make the work challenging and rewarding so that his people will remain with the organization for many years. This allows it to benefit fully from their knowledge, experience, and corporate memory.”

Industrial State Capacity

Rickover’s scrutinizing style of management extended to the private companies he worked with. He pioneered the practice of project officers, who lived on-site at the projects and who would report directly to him any delays or unforeseen issues, so that Rickover could escalate immediately and ensure the project remained on track.

Government contracting was, and still is today, a largely passive and administrative activity. While Rickover acknowledged that the government was the “customer” and the contractor was the one responsible for delivering, Rickover’s unique approach to program management was exercising tight oversight over the contractors. Rickover hired technical experts into his office and then sent them out as project officers to oversee the various contractor sites. There, the project officer was expected to be the active representative of the Naval Reactors Office, reporting directly to Rickover any issues with contractors and ensuring the contractor was on track to deliver the product as expected. In every sense, Rickover’s project officer was to be his eyes and ears on the ground. Rickover took great pains to ensure there was no customer capture, telling one of his project officers, “Don’t go to dinner with them. Your wives must not get friendly with their wives. You’re not even to let your dogs get friendly with their dogs…when you do that, you become one of them…you don’t represent me anymore”.

Rickover’s success in scaling industrial technology was demonstrated early on with Zirconium production. In 1949, the world had only produced a shoebox worth of purified Zirconium, but the material showed promise as a fuel cladding material due to its durability under high temperatures without blocking the emitted neutrons needed to enable fission reactions. AEC opened up a simple contract for private companies to bid to produce Zirconium, but none of the companies were able to scale up production. Rickover took over production a year later, applied his practice of close project management with the (now defunct) Bureau of Mines, and only then passed it off to industry:

But by 1949, when Rickover was looking to scale up promising fuel cladding material production, the AEC had already decided to run contracts through another AEC division. Unable to exert the centralized control over the contractors, the AEC manufacturers were slow to scale up a high-quality production process. In 1950, after a year of delay, Rickover finally received permission to have the Westinghouse Bettis site directly manufacture Zirconium metal and worked with the Bureau of Mines (BuMines) to purify the Zirconium. Under Rickover’s scrutiny, Bettis scaled a novel purification process to thousands of tons of production capacity. Rickover opened up contract bids for Zirconium only after having derisked this novel technology. When the Secretary of the Navy later asked Westinghouse how they managed to scale up this process, the response he got was “Rickover made us do it”.

“The man in charge must concern himself with details. If he does not consider them important, neither will his subordinates.”

Bureaucratic Innovation

Building big things requires lots of people. Rickover was not only an exceptional manager of people and deeply technical, but his 20-year naval career before Oak Ridge taught him how to wrangle government bureaucracy — and discern which rules mattered and which didn’t. For example, Rickover was interviewing an officer who thought the monthly reports on the gasoline usage of his base’s motorboats were pointless and wasteful. Rickover told him to simply remove the tickler file that tracked the reports from the boss’s secretary file and to send over a note the next day alerting Rickover that the task had been completed. The interviewee did and was hired.

Rickover’s bureaucratic skill is exemplified by his success in rallying the Navy behind the nuclear-powered submarine. He believed this was a feasible, near-term project, despite widely-held convictions to the contrary — including those of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). Even Robert Oppenheimer (who served as one of the first AEC commissioners) doubted nuclear propulsion early on.

In light of initial resistance from the civilian AEC, Rickover formulated a unique bureaucratic innovation to position himself within two chains of command — one within the Navy and the other within the AEC.

Rickover was also able to realize his bureaucratic innovation to occupy a spot on the org chart both at AEC and in the Navy BuShips, something he first formulated while at Oak Ridge. This way, if the AEC refused something, he could respond that “this is a priority for the Navy” and vice versa. Similar to how the Manhattan Project reduced risk by pursuing parallel technological approaches, Rickover would reduce his bureaucratic risk by pursuing parallel chains of command. This unique structure lives on to this day, with Naval Reactors shared between the semi-autonomous National Nuclear Safety Administration (NNSA) in the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Navy.

“The status quo has no absolute sanctity under our form of government. It must constantly justify itself to the people in whom is vested ultimate sovereignty over this nation”

Rickover firmly believed that the right team and the right culture could build incredible industrial technologies at scale, even within the government. While discourse in Washington DC often focuses on regulations or money, Rickover’s life brings a uniquely human-centered view of industrial policy: one that recognizes the importance of state capacity, technical personnel, and most importantly, public leaders with the vision and drive to build technology.

This guy sounds like Jensen

Very excited to read more about Rickover