SB 1047 with Socialist Characteristics: China’s Algorithm Registry in the LLM Era

What do the regs really do?

ChinaTalk first covered China’s algorithm registry nearly two years ago, back when it was a freshly minted, relatively untested apparatus. How has the system evolved since then? Pseudonymous contributor Bit Wise fills us in.

In July 2023, China issued binding regulations for generative AI services, which, notably, require output generated by chatbots to represent “core socialist values.” These regulations have stirred debate on how tough the Chinese government is on AI: are regulators putting “AI in chains,” or are they giving it a “helping hand”?

These debates have largely focused either on the text of the regulations or on its evolution from a stringent draft to a more lenient final version. What has received less attention is how the regulations are actually being implemented now.

Does China have a genAI licensing system?

In this post, we unpack one key enforcement tool of the Interim Measures: mandatory algorithm registrations 算法备案 and security assessments 安全评估.

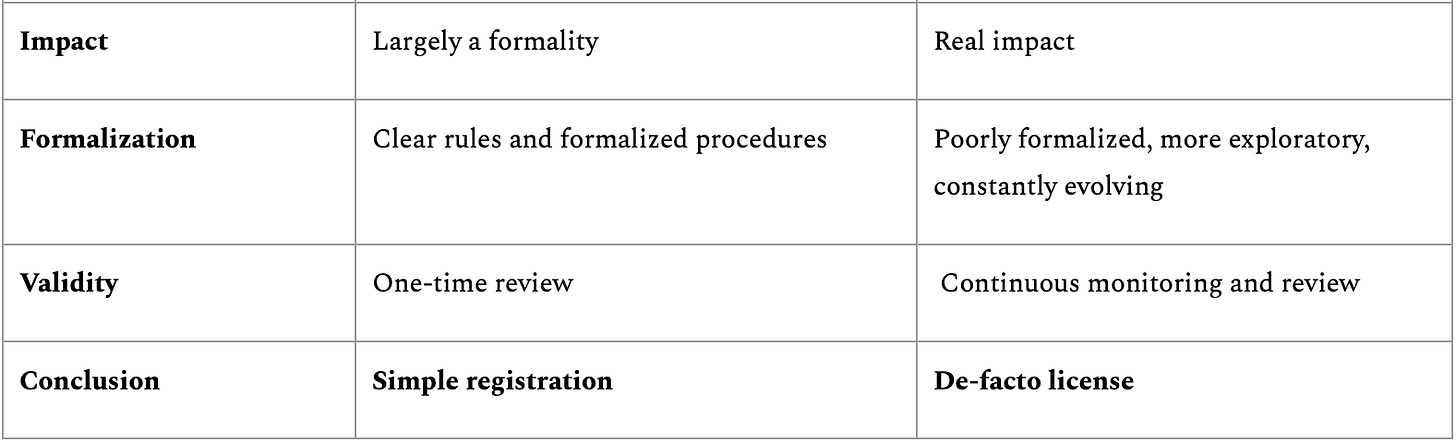

Even though the algorithm registry is a central enforcement tool in China’s AI regulations, it is still relatively poorly understood. One big open question is: should we think of it as mere registration, or rather as a de-facto licensing regime?

Two leading scholars on China’s AI policy have come to essentially opposite conclusions (emphasis added):

Angela Huyue Zhang (p. 46): Lawyers have observed that many AI firms are now merely required to register their security assessment filings with local offices of the CAC, instead of obtaining a license before launching public services.

Matt Sheehan (p. 32): [I]n practice regulators began treating the registration process more like a licensing regime than a simple registration process. They did this by withholding their official acceptance of registrations until they felt satisfied with the safety and security of the models.

The two interpretations have widely different implications. A simple registration system would imply a light-touch approach to AI governance. A licensing system, on the other hand, would allow the government to control which models go online — making it a much stronger tool for social control at the moment, but potentially also a more formidable instrument for governing future frontier AI risks.

In this post, we try to get to the bottom of how the genAI registrations actually work.

A note on methodology

We have thoroughly reviewed Chinese-language official policy documents and Chinese legal analysis on the algorithm registry. To triangulate our findings, we have also spoken with several Chinese lawyers with direct experience guiding AI companies through the filing process. These interviews took place from April to June 2024. We are incredibly grateful to every one of them for their willingness to share their insights! We also thank Matt Sheehan for providing valuable feedback on a draft of this post.

Some evidence, though, remains messy, as our sources contradict each other at times. In fact, a common theme recurring throughout our sources and conversations was that the procedures are poorly formalized and constantly changing. This post won’t be the final word on how China’s algorithm registration process works.

Algorithm registry: a short history

The algorithm registry pre-dates the genAI era. It was first introduced in March 2022 with regulations for recommendation algorithms:

Article 24: Providers of algorithmic recommendation services with public opinion properties or having social mobilization capabilities shall, within 10 working days of providing services, report the provider’s name, form of service, domain of application, algorithm type, algorithm self-assessment report, content intended to be publicized, and other such information through the Internet information service algorithm filing system.

第二十四条 具有舆论属性或者社会动员能力的算法推荐服务提供者应当在提供服务之日起十个工作日内通过互联网信息服务算法备案系统填报服务提供者的名称、服务形式、应用领域、算法类型、算法自评估报告、拟公示内容等信息,履行备案手续。

The fact that filings need to be completed within 10 working days of providing services suggests that it was envisioned as a simple post-deployment registration, rather than a pre-deployment license.

The regulation also requires “security assessments” 安全评估:

Article 27: Algorithmic recommendation service providers that have public opinion properties or capacity for social mobilization shall carry out security assessments in accordance with relevant state provisions.

第二十七条 具有舆论属性或者社会动员能力的算法推荐服务提供者应当按照国家有关规定开展安全评估。

In late 2022, regulations on “deep synthesis” algorithms essentially repeated the same requirements; the only minor difference between these regulations was that they defined two separate entities: service providers 服务提供者 and technology support 技术支持者. Slightly different procedures apply to each, but both have to do algorithm registration and security assessments. In practice, one company may file the same model as both a service provider and tech support, if it offers distinct products. For example, Baidu’s ERNIE model 文心一言 has one filing as “service provider” for its consumer-facing mobile app and website, and a separate filing as “technology support” for enterprise-client-facing products.

Note: the definition of “deep synthesis” largely overlaps with that of generative AI. Hence, most generative AI models, such as ERNIE bot, actually undergo model registration under this deep-synthesis regulation.

GenAI regulations: continuity?

So what do the 2023 genAI Interim Measures say? Essentially the same thing!

Article 17: Those providing generative AI services with public opinion properties or the capacity for social mobilization shall carry out security assessments in accordance with relevant state provisions and perform formalities for the filing, modification, or canceling of filings on algorithms in accordance with the “Provisions on the Management of Algorithmic Recommendations in Internet Information Services.”

第十七条 提供具有舆论属性或者社会动员能力的生成式人工智能服务的,应当按照国家有关规定开展安全评估,并按照《互联网信息服务算法推荐管理规定》履行算法备案和变更、注销备案手续。

All of this suggests continuity: we know what this algorithm registry is from previous regulations — now we just apply the same tool for genAI services.

In reality, however, the procedures for genAI models work fundamentally differently from how they worked for other AI systems (such as recommendation algorithms) in the pre-genAI era.

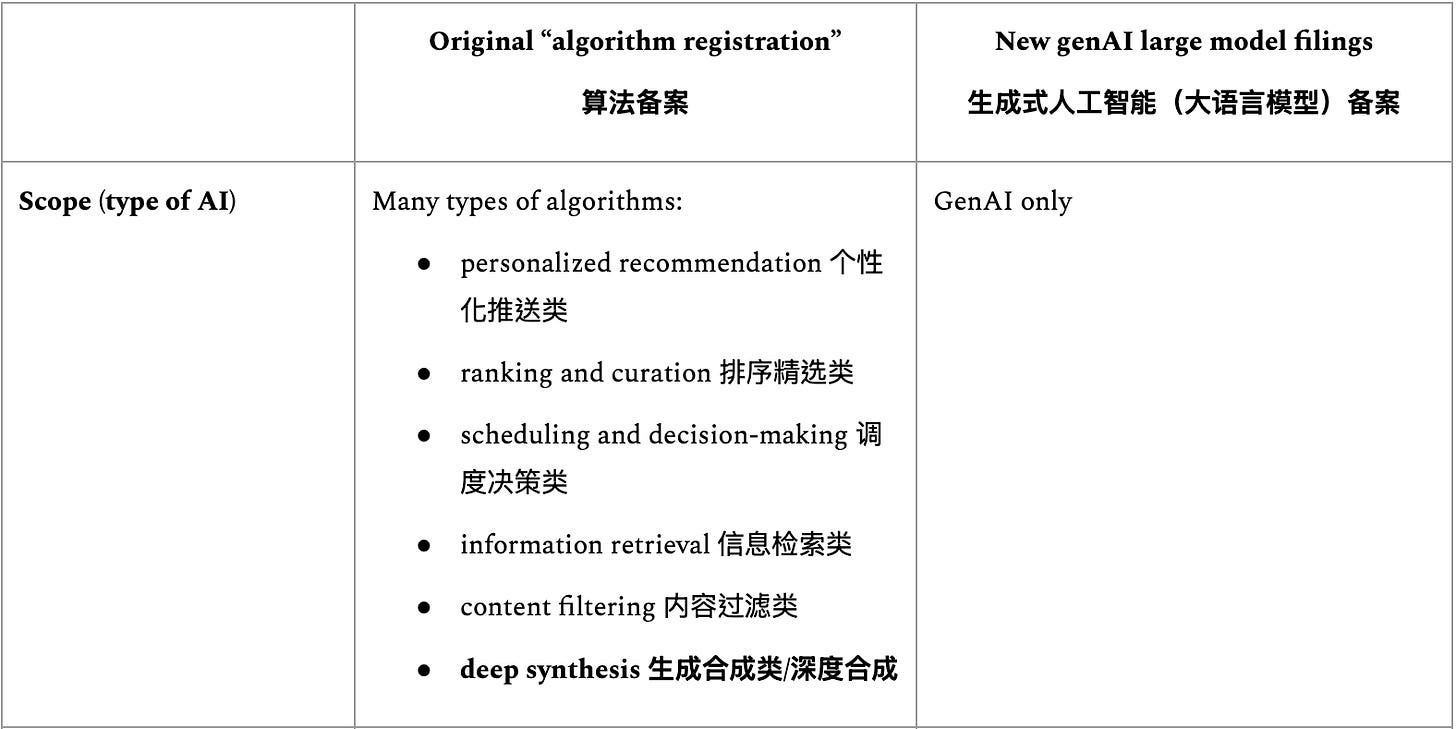

The previous system is still in place, but an additional system just for genAI services has been established in parallel. Chinese lawyers describe a de-facto “dual registration system” 双备案制, consisting of

the original “algorithm registration” 算法备案, and

a new “genAI large model registration” 生成式人工智能(大语言模型)备案.1

How do the two systems work?

The new system has not replaced the old system. Rather, they co-exist in parallel. Companies typically first undergo the regular “algorithm registration.” For some, the story would end there. For some genAI products, however, authorities would then initiate the more thorough “genAI large model filing” as a next step. The scope of services affected by this additional registration process is somewhat unclear, but it generally applies to all public-facing genAI products (or, in Party speak, models with “public opinion properties or social mobilization capabilities” 具有舆论属性或者社会动员能力). Public-facing genAI includes all typical chatbots or image generators available through chat interfaces and APIs.

Information on how the two systems differ is piecemeal. But many sources confirm the same bottom line:

The original “algorithm registration” is relatively easy and largely a formality;

In contrast, the new “genAI large model registration” is much more difficult and actually involves multiple cycles of direct testing of the models by the authorities.

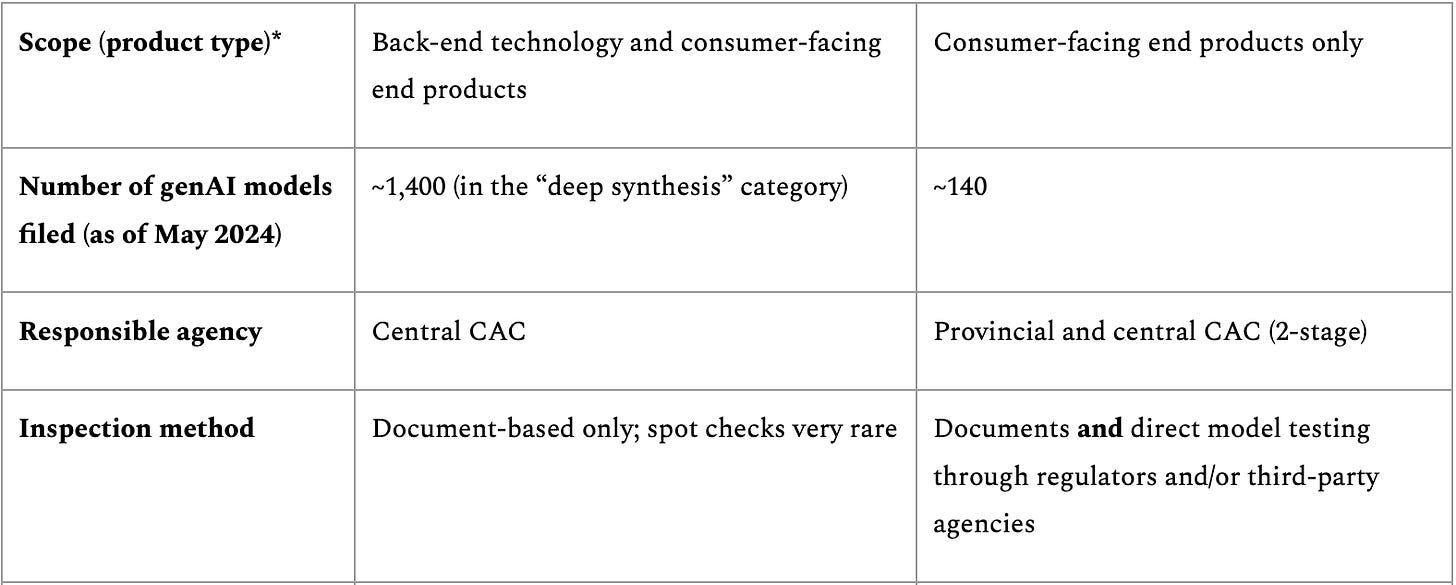

The table below summarizes the key differences.

The term “genAI large model filing” is not actually used by China’s regulators. The CAC gives only one small hint that something has changed: the filing information of genAI models is published not through the regular algorithm registry website, but through provincial-level CACs. The central CAC compiles these announcements into a separate announcement on its website,2 which is distinct from the regular algorithm registry website. This subtly hints at the fact that these are two separate systems.

As one Chinese lawyer aptly put it,

Practice started first, and then formal law-making may follow later.

Foreign AI policy analysts are also not the only ones feeling confused. As the same lawyer noted,

When more than one “security assessment” system exists at the same time, companies will inevitably be confused.

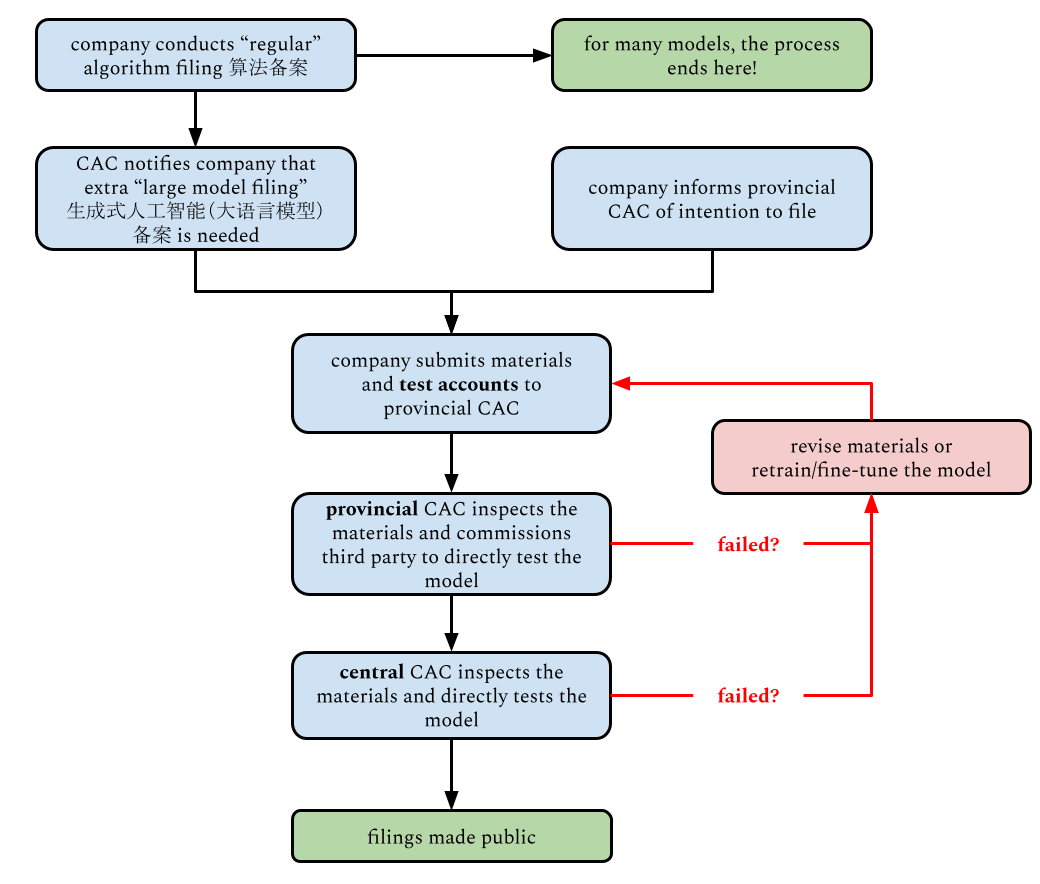

The graph below summarizes the procedure for the new “genAI large model registration”:

A company would typically start with the “regular” algorithm registration. For many models, this would be it! Public-facing products, however, would then be asked to conduct the additional genAI large language model filing. As mentioned above, there is lots of ambiguity on which models are considered “public-facing”. Some anecdotes shared by industry insiders suggest that the scope is interpreted relatively broadly in practice, and may include some products only intended for enterprise users.

Apart from submitting documentation on internal tests (which we will cover in a forthcoming post), the companies need to create test accounts for the provincial cyberspace authorities, granting them access to test the model pre-deployment. Some Chinese lawyers told us that CAC has outsourced these tests to third-party agencies, but we do not have any insight into which institutions these are. The process can involve multiple rounds of renewed fine-tuning until the CAC is satisfied with how the model behaves.

There is no official information on what the CAC (or its endorsed third-party institutions) actually tests in these inspections. All insiders we talked to, however, agreed that content security will be front and center.

Oversight may have evolved beyond a one-time licensing process to a more dynamic approach, similar to how the PRC regulates online content generally. It appears there is ongoing communication between the CAC and AI service providers even after a model went online, mirroring the relationship between regulators and traditional online content platforms.

As mentioned before, some details remain confusing, as different sources contradict each other. For instance, there is conflicting information on whether companies themselves initiate the process, or whether it always starts from a CAC request after the regular model registration. There is also conflicting information on the role of provincial CACs. Some sources claim that they conduct tests on their own, while others claim that they just forward documents to the central CAC. It is possible that both claims are true and that it differs by province, but this is speculation.

Changes in the making?

A running theme throughout all our sources and conversations was that the new processes are still poorly formalized and constantly changing. What happened to one company may be different from what happened to another; what happened three months ago may be different from what happens now.

One Chinese lawyer told us that the CAC struggles to keep up with the large number of filings, so the agency is considering a risk-based categorization, after which only a smaller number of high-risk models would have to undergo the more thorough registration process. This would be a familiar story: in spring 2024, the CAC relaxed data-export security assessments because, among other reasons, the authorities could not keep up with the large number of applications.

There are no official details on when or whether such ideas may become reality for genAI registrations. In August 2024, however, CAC head Zhuang Rongwen 庄荣文 proclaimed that CAC would “adhere to inclusive and prudent yet agile governance, optimize the filing process for large models, reduce compliance costs for enterprises” 坚持包容审慎和敏捷治理,优化大模型备案流程,降低企业合规成本 and “improve the safety standard system in aspects such as classification and grading” 在分类分级、安全测试、应急响应等方面丰富完善安全标准体系. This shows that regulators are still actively exploring ways to tweak the algorithm registration process.

How hard is it to get through this process?

According to CAC, as of August 2024, 190 models have filed successfully. There is no good data on how many models have not passed the filing process; the government releases only successful filings, not failed ones. As one of the lawyers we spoke to pointed out, it is not even really possible to “fail” the process. If you do not pass, you adjust your model and try again. Some companies, though, might get caught up in this circular process for a long time.

In May 2024, China tech news outlet 36kr estimated that there are 305 models in China, of which only around 45% had successfully registered at the time. This rate doesn’t necessarily imply that the other models have failed their applications. For instance, 60 of the 305 models have been developed by academic research institutions; it’s possible that those institutions never intended to put them online in the first place, and thus never tried filing.

Implications

The main goal of this post was simply to provide insight into how algorithm registrations for genAI products in the PRC work right now. But what does it all mean for China’s AI industry? What does it mean for AI safety?

It is clear that Chinese regulators get pre-deployment access to genAI products, and can block them from going online if they are not satisfied with content control or other safety issues. This may mean that,

The enforcement of China’s genAI regulations is somewhat stricter than that of previous AI regulations, such as those for recommendation algorithms — suggesting the PRC sees a greater threat in genAI compared to previous AI systems;

Regulatory hurdles for providing public-facing end-user products are significantly higher than for enterprise-facing products. It’s possible that some companies will increasingly focus on B2B rather than B2C, or launch products overseas first while waiting for filing results in China.

Much more to cover

As part of the “genAI large model registration,” AI companies need to submit a number of attachments, such as

Appendix 1: Security Self-Assessment Report 安全自评估报告

Appendix 2: Model Service Agreement 模型服务协议

Appendix 3: Data Annotation Rules 语料标注规则

Appendix 4: Keyword Blocking List 关键词拦截列表

Appendix 5: Evaluation Test Question Set 评估测试题集

The state has published detailed technical guidelines for these. In our next post, we will make a deep-dive explainer of the technical AI standard that covers the processes for Appendix 3, 4, and 5. So keep an eye out on your inbox!

In summer 2023, some lawyers initially referred to the “genAI large model registration” as “security assessment 2.0” 安全评估 2.0. That was because the state was falling back on a security assessment for “new technology or new applications” 双新评估, introduced way back in 2018. These assessments would also involve the public-security organs beyond the CAC. The April 2023 draft of the genAI regulation referenced this type of security assessment — but this regulation was just a temporary arrangement. Since the issuance of the final genAI regulations, only the term “genAI large model registration” 生成式人工智能(大语言模型)备案 is widely used, and it’s clear that the CAC is the only government agency responsible for enforcement.

The central CAC announcement is updated only periodically. At the time of this writing, the announcement has been only updated twice, in April and August 2024. Provincial registrations are updated on a rolling basis via provincial cyberspace bureaus’ WeChat public accounts.

Very cool