Recently at a CSIS event, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer laid out his framework for legislating on AI. In an optimistic reading of the history of American innovation, Schumer explained,

It was America that revolutionized the automobile. We were the first to split the atom, to land on the moon, to unleash the internet, and create the microchip that made AI possible. AI could be our most spectacular innovation yet, a force that could ignite a new era of technological advancement, scientific discovery, and industrial might.

Most politicians and commentators of late have focused exclusively on the downsides AI poses. But Schumer emphasized, “Innovation must be our North Star. … The US has always been a leader in innovating on the greatest technologies that shape the modern world.”

Schumer’s recognition that innovation has long been the US’s secret weapon is remarkable and bodes well. He continued,

If applied correctly, AI promises to transform life on Earth for the better. It will shape how we fight disease, how we tackle hunger, manage our lives, enrich our minds, and ensure peace. … We have no choice — no choice — but to acknowledge that AI’s changes are coming and in many cases are already here. We ignore them at our own peril.

To be sure, Schumer’s speech makes pointed references to the challenges AI will pose to society. He specifically mentions: near-term structural unemployment, IP theft, the enabling of anti-democratic forces — specifically the CCP, as well as those seeking to undermine US elections.

The policy questions he chose to highlight are critical ones that ChinaTalk has been exploring extensively in recent years.

One, what is the proper balance between collaboration and competition among the entities developing AI? [ChinaTalk’s take]

Two, how much federal intervention on the tax side and on the spending side must there be? Is federal intervention to encourage innovation necessary at all? Or should we just let the private sector develop on its own? [ChinaTalk’s take]

Three, what is the proper balance between private AI systems and open AI systems? [ChinaTalk’s take]

And finally, how do we ensure innovation and competition is open to everyone, not just the few, big, powerful companies? The government must play a role in ensuring open, free, and fair competition.

I appreciate how Schumer is taking an appropriately humble approach to projecting AI’s future. “We don’t know,” he said, “what artificial intelligence will be capable of two years from now, fifty years from now, 100 years from now.” The worst thing policymakers could do for American competitiveness is to apply, as Stewart Baker recently characterized Europe’s approach, “EUthanasia” to AI such that we lose out on the benefits of the technology.

I discussed with Jeff Ding on the show last month how GPTs — general-purpose technologies like electricity and, potentially, AI — are true “engines of growth” and serve as the path to sustained productivity increases across decades. National power is downstream of a large economy. Lawmakers’ first and foremost aim should be to ensure that American businesses and bureaucracies can take advantage of AI’s promise, while also limiting downside risk and ensuring adversary nations don’t use this technology to leapfrog America. It seems to me that Schumer and his team are on the right track.

ChinaTalk is Hiring!

With three of ChinaTalk’s editors heading to grad school this fall, I’m looking to bring more part-time editorial support on board. If you’re interested in a 5-10-hour/week position for the next few months helping to put together this newsletter while getting to do your own original coverage on modern China, consider applying!

Irene—Chinese Women’s Lives on the Margins

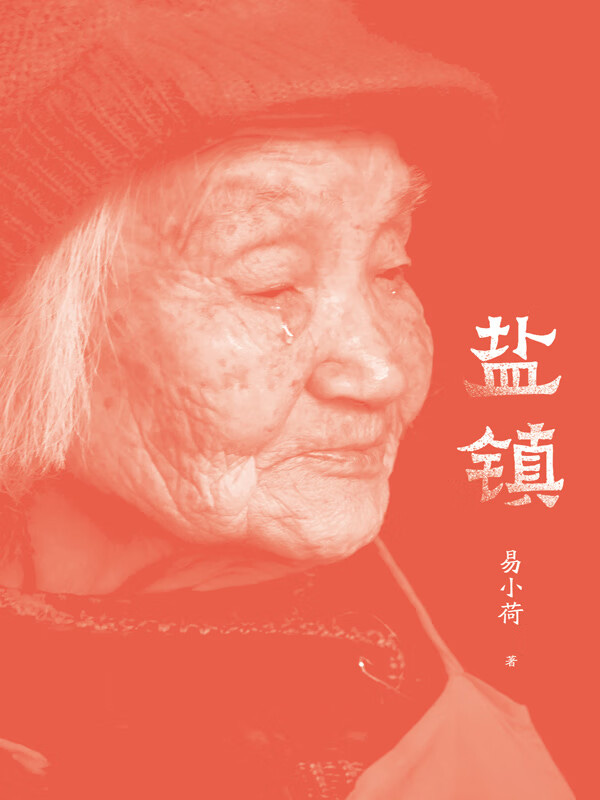

Yi Xiaohe 易小荷, a respected journalist formerly of Southern Weekly, published a new book in February, which I’m very excited to read in full after seeing an excerpt recently. Yi is from Zigong 自贡, a salt-producing part of Sichuan which used to be among China’s wealthiest locales but is now in decline. After a career setback in 2021, she moved from Shanghai to a small town in Zigong for eighteen months to write Salt Town 盐镇, a work of nonfiction documenting average women’s lives in China’s margins.

There are no churches here; the master at the temple spends most days performing morning and evening chants in solitude. Whenever a family faces a problem they can’t solve, the most common response is to ask for advice from the clairvoyant lady in the next village. She always tells them, in the voice of their relatives in the underworld, that there are still people who care about them in this universe and that all shall be well.

Life in the salt town is made up of countless thin, broken wounds; the women try desperately to stop the bleeding, while the men scatter more salt.

Listen to Yi Xiaohe discuss her year in Zigong on the 看理想电台 podcast here.

Bryan Cheong — ChinaTalk’s Chief Tea Correspondent — on a Summer Green

In warmer weather I turn to green teas. The long straight needles of 2023 Ming Qian Anji Bai Cha 明前安吉白茶 from Seven Cups look like pale alpine fir needles. Unfurled in water, they turn pale green, less white-ish than previous years, as the name Bai Cha (or White Tea) suggests.

These tea buds are picked in a very narrow window of time — before they have time to turn dark chlorophyll green and capture the returning spring sunlight — and are then justled in long semi-circular heaters so they have a uniform needle-point shape. The consumer may have their demands for uniformity from year to year, but what avails such demands to nature and to a plant like the tea tree?

Anji Bai Cha is quite a modern tea, cultivated from tea bushes found in Anji County in Huzhou, Zhejiang, in 1982, and named after a tea that delighted the Song dynasty Emperor Huizong 宋徽宗. The Emperor Huizong in his Treatise on Tea 大觀察輪 wrote of a translucent tea grown only in four or five households, each with only one or two tea trees, that was beyond compare. An imperial connection, however tenuous, is excellent for marketing.

The Emperor was an aesthete so in love with art that he is almost a caricature of the Song Dynasty itself. He invented a calligraphy style “slender gold” 瘦金體. His brushstrokes seem fragile, just like the needle leaves of Anji Bai Cha named in his honor. Unfortunately, his taste in culture didn’t help him much politically: he died in captivity as a prisoner of the Jurchen Jin Dynasty.

Despite appearances, the summer has relaxed Seven Cups’ Anji Bai Cha from its initial greenness. To the nose, the dry leaf smells like the fresh rolled oats of a Saturday breakfast. It has the creamy note of freshly boiled green soybeans. In the mouth, it is smooth, gentle, calming, and above all, clean. It is the subtle, jade-like, green-gold tea to clarify a muggy summer day.