Scientists and the State

Yangyang Cheng on international collaboration, China-related discourse in the West, CERN and brain drain

FYI, I’ll be in Austin for the next week or so if anyone is around and would like to meet up.

Is the treatment of China in Western public discourse inevitable? Yale Law School postdoc, particle scientist and essayist Yangyang Cheng (@yangyang_cheng) joins me and Yale's Alex Liang to talk about understanding the other, how the personal can be lost in the noise of geopolitical tension and science across borders.

From the “new red scare” to Higgs Boson parties, we discuss international scientific cooperation among countries that are none too friendly with each other, borders, why Yangyang doesn’t like “brain drain,” and more. For the full episode, check out the ChinaTalk podcast here.

Transcription by Callan Quinn.

Jordan: Let’s start with a reading!

Yangyang Cheng: I published this essay in the New York Times in April 2020 when the Covid-19 pandemic was raging in the US and when the lockdowns had just started. It is a conversation between my mother and I. My mother lives in China.

Eleven years ago when I was preparing to leave China, my mother impelled me to do two things: get baptized and join the Chinese Communist Party. She was petrified at the thought of me alone in a foreign country. She wanted me to carry the memberships like talismans so that the two most powerful entities in this world and the next one would bless my journey.

I fulfilled neither of her wishes. I am not a Communist, and I do not believe in God. I am a scientist and a writer. It is the responsibility of my vocations to ask the questions obscured by simplified answers. But what happens when the questions I ask can never be answered, when a puzzle has no solution, when every option is wrong?

It is now the beginning of April, and the United States has the most reported cases of Covid-19 in the world. On the first day that the people of Illinois were put under a shelter-in-place order, when the clock struck 7 p.m., thousands of Chicago residents walked to their balconies to sing Bon Jovi’s ‘Livin’ on a Prayer.’

As dusk sets over the city I call home today, it is a new morning for my mother in China. I can picture her standing in our old kitchen, her graying hair tied up in a messy bun. She adds nuts and dried fruit to her congee. She reads the news from state media. The kettle chirps on the stove. She fills two thermal flasks with hot water and looks out the window. She thanks God for her meal and asks him to look after her only child.

My inbox will soon light up again with messages from my mother. She will continue to write while I sleep. I imagine a tunnel opening up through the planet, where our thoughts meet.

I enjoy putting ChinaTalk together. I hope you find it interesting and am delighted that it goes out free to eight thousand readers.

But, assembling all this material takes a lot of work, and I pay my contributors and editor. Right now, less than 1% of its readers support ChinaTalk financially.

If you appreciate the content, please consider signing up for a paying subscription. You will be supporting the mission of bringing forward analysis driven by Chinese-language sources and elevating the next generation of analysts, all the while earning some priceless karma and an ad-free feed to the podcast.

Making a people and culture one dimensional

Jordan Schneider: You have this beautiful line and in one of your essays: “the Chinese language I speak, Standard Mandarin, is as old as Chinese civilizations and as young as the modern Chinese state.”

It stands in for just a broader feeling which you and I probably both have when you see China referred to in political discourse as a sort of distilled down, simplistic, one-dimensional entity and where all the people and the culture and the history are reduced to whatever a politician or think tanker decides is the meaning of it.

Is there something inevitable about this sort of treatment of China in the popular discourse nowadays in the West?

Yangyang Cheng: It's a great question. And it's an urgent one with a lot of stakes. I’ll answer this from two aspects. The first is with regards to how the West imagines China.

I think it is interesting because “the West” is an imperfect phrase. I would quote the Caribbean philosopher Édouard Glissant, who said “the West is not in the West. It is a project, not a place.”

The very creation of the West is aligned with state interests, with capital interests, with imperial interests and with power structures.

So what is China? Coming to my second point and, as you quoted this line that I wrote about in The Guardian earlier this year about whether or not one needs to speak Chinese to know China, I think language is not a neutral thing. Language is a tool of power and it contains history.

It has context. The Chinese language - Chinese languages - both through history and in its modern form, are all closely aligned with nation-building, with projects of the state and with power.

And so it's an evolving thing. It's not something that is set in place and the identity associated with it is also fluid. There is so much richness from this and Chinese languages - Sinitic and non-Sinitic - spoken in the region that we know as China today.

If we flatten all of those into a geopolitical concept, which benefits a lot of Western state interest but also to a great extent benefits the Chinese state interest, it's really a great loss. Not just for Chinese people or Chinese culture, but for humanity and for history.

Myself, I was born and raised in China. I’m a Chinese citizen but I regard my Chinese identity as cultural and linguistic. It is not something that is dictated by the state.

In a lot of my writings, I'm also trying to contest that, to wrestle and to reclaim my Chinese identity from that very narrow one-dimensional, flattened concept created by the state, whether that is the Chinese government or the US government or some other geopolitical power.

The history of scientists and the Chinese state

Jordan Schneider: I'm pretty sure Yale Law School doesn't make you teach right now, but if they did who and would you want to put on the syllabus? Are there any interesting Chinese and non-Chinese thinkers that you would want to pair together?

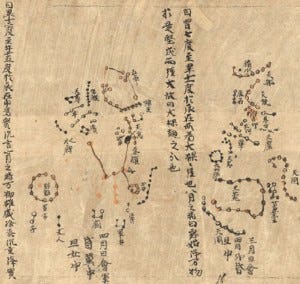

Yangyang Cheng: One course that I've actually wanted to teach if I were given the opportunity is a course examining the relationship between science and scientists vis-a-vis the Chinese state over millennia to the present day.

And in this process, there are also comparative aspects. For example, early Chinese science and scientists can be compared to early Greek science and scientists of a similar era.

Science and technology in China have never been an insular affair. But how they are used and how much is indigenous versus an import is very much also related to the political, social and economic conditions of the time. I think that would actually be an interesting course.

And then we could also read a lot of Chinese thinkers from earlier years writing about pre-modern astronomy’s relation with the state, and the body, the state and the cosmos as reflections of each other.

[And then you could go] up to the 19th century during the self-strengthening movement and how some of the writers and politicians thought about the role of Western technology, and in particular military technology, for self-strengthening and then later for national salvation.

And then to the present day, there are also a lot of Chinese language sources, as well as English language sources, that we can read about this.

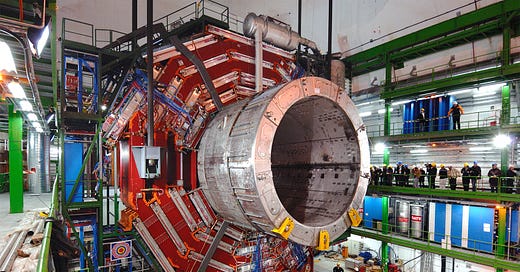

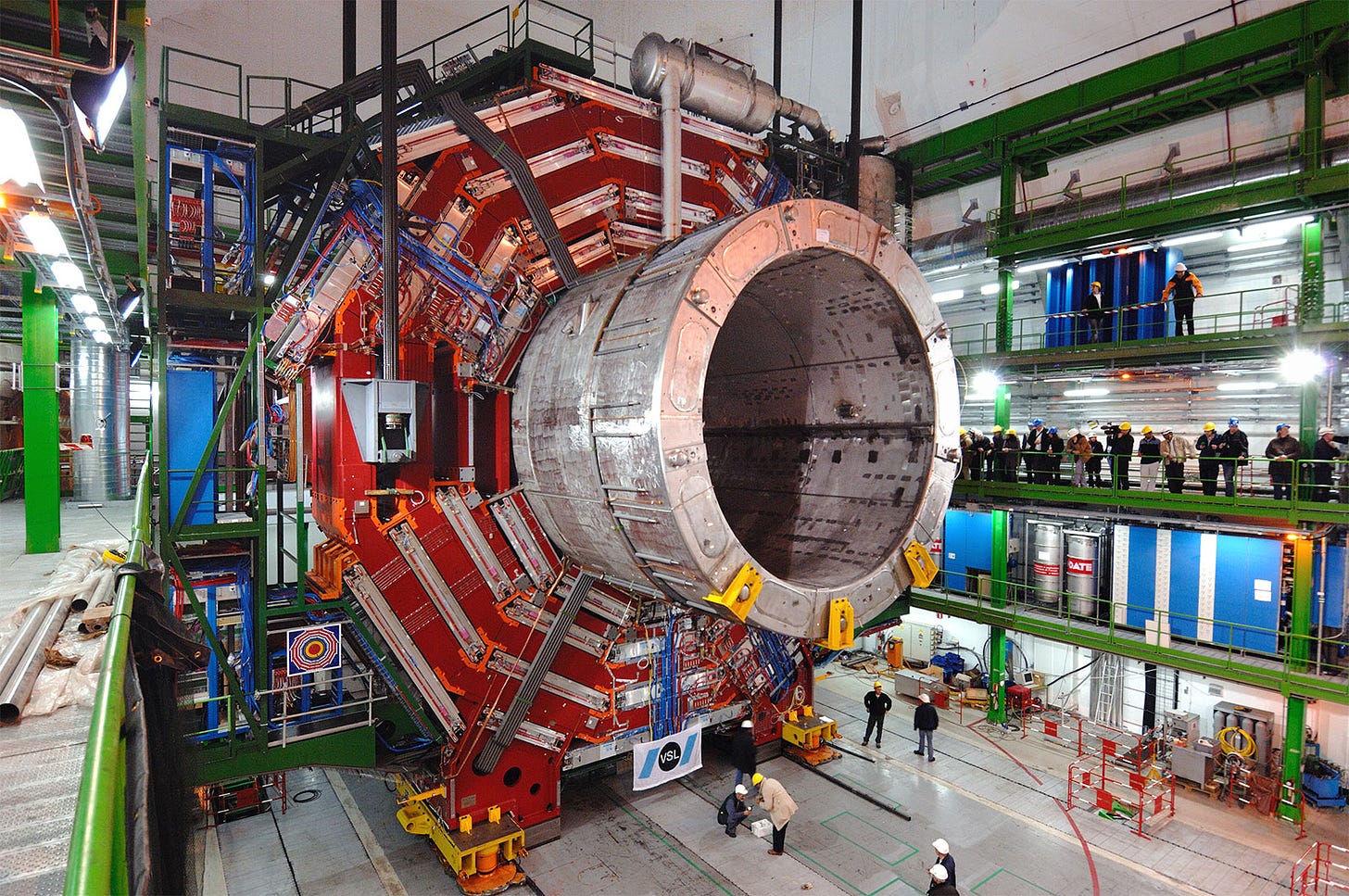

The Large Hadron Collider

Jordan Schneider: Yangyang, I want to take a little detour into the Large Hadron Collider. Well, maybe not into it, but first a story and then a question. So for whatever random reason I was in Geneva the day they announced that they had found the Higgs Boson and had the chance to party with all of those physicists that night.

A few of my friends were interns there and it was the most incredible moment with all these people from all around the world just being really happy. I think there's some sort of vision baked into the Large Hadron Collider and those sorts of international scientific projects which is really antithetical to a lot of the discourse both in the US and in China when it comes to the purpose of science and the reason that nations put money into these sorts of projects.

In China, it's all about self-reliance and making China great again. In the US, we have this rhetoric around internet competitiveness. But as an outside observer, at the same time, there's something really pure and beautiful about humanity and the fact that the world got together and built the Large Hadron Collider.

Am I missing something? Is there something special in that community? What's your take from the inside? And if you are going to pause and spend two years writing about all the themes that came out of your experience in that community, what are some of the threads you'd like to unfurl?

Yangyang Cheng: That's such a lovely story. The Higgs Boson was discovered actually on July 4th. I was a grad student at the University of Chicago at the time, but I did wake up at about 3:00 am to watch the live stream.

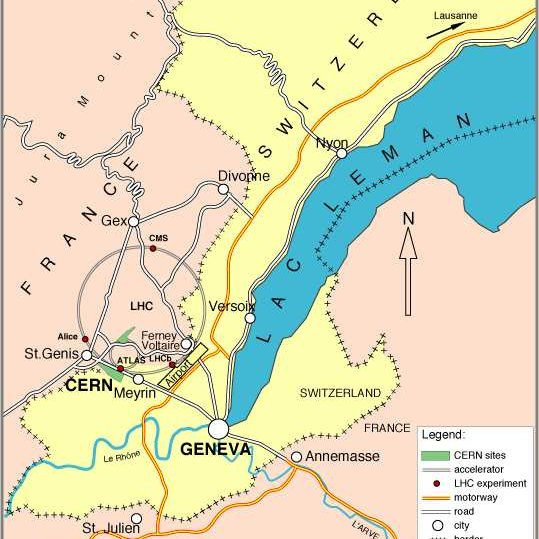

So, I should acknowledge the ideas and also point out some of the constraints of reality and also make some reference to the history. The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), was founded in the mid-1950s and is where the Large Hadron Collider is located.

It was founded as a research center, but it also from its founding had a very explicit geopolitical goal within the context of politics on the European continent shortly after World War 2.

Europe had been ravaged by war and then the nations and individual national governments came together and thought [about the creation of] a scientific project that could to some extent help to unite these countries that had been trying to decimate each other for so long.

The choice to build it on the Franco-Swiss border is a reflection of that. So it does have a cosmopolitan ideal. And, as you mentioned, it is a large international collaboration with dozens of member countries and hundreds of institutions from all over the world.

I think that was one of the things that really drew me to particle physics when I was still an undergraduate student in China. I was really curious about these fundamental questions about nature. I was amazed by the majestic instrumentation and I've always been interested in and worked a lot on the hardware side of it.

Finally, there is also the aspect that I was intrigued by the nature of the collaboration. How can people from such diverse backgrounds and nationalities - and a lot of these countries are not very friendly with each other - work together for a very long time? And also, in the present sense, work together on something beyond immediate utilitarian purposes?

I think these are inspirational examples, but then I would come to the pragmatic part of it. I do not want to give the impression that somehow CERN is an ideal and that it is perfect. It is very much not. As I mentioned earlier, it is an experiment located in Europe.

This is not an individual's fault, or the fault of CERN management or anything, but this is a result of global geopolitics and these power structures, right?

Not all passports are created equal. So if it's a large international collaboration, how do people travel? And also it's related to where the state of social economic development with a state and educational and scientific infrastructure in one's native country.

And so right now collaboration at CERN is still very much a white male majority, Europe and North America dominated project. Particle physics in general is [like that], and is probably also not so different from a lot of other branches of physics.

How do we democratize the scientific profession on a global scale? That is a very important question. And that is a responsibility of the scientific community, of the political policymakers and also the public in general.

To give a very immediate example, CERN is built on the border. Many of my colleagues live in France because the rent is cheaper but they may access civil services like their doctors on the Swiss side.

With the Covid pandemic, Switzerland and France began to enforce their borders and it created very significant problems.

For various reasons, like for pandemic control, it can be valid, but we also need to understand that a national border is not a magical boundary. It is not the most optimized boundary for containing a pandemic. It's simply because it is the boundary that is aligned with organized state power.

So these are our realities that we have to contend with. But I also wanted to point out one thing that I think is still a lesson that we can reflect on today: during the Cold War when the Soviet Union was, largely by its own design, closed off to the West, there were Soviet scientists at CERN first and then later at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory just outside of Chicago.

A lot of particle physicists did leverage their institutional prestige and their political connections and lobbied their national governments to create these channels for Soviet scientists to come work at CERN and Fermilab.

Soviet scientists still couldn’t travel freely and had to travel with their government minders. That was something that carried a degree of security risk, but that risk was weighed against the benefits.

It was also a time when the world was on the verge of nuclear war so actually having these kinds of conversations open between nuclear and particle scientists and understanding what each other was doing was actually constructive to peace.

I think that was an important lesson that has particular relevance today as well.

Jordan Schneider: It's interesting because you saw the scientific collaborations between the US and Soviet Union cooperating on space-related projects getting into the seventies and eighties, and saw that impetus to use science as a bridge.

You don't see that a lot in 2021, even though the world seemed a lot scarier and the risk of nuclear war was probably higher back then than it is today. Is there something about the way the world looks between the US and China where no one is really that scared of some existential crisis and so you don’t see anyone advocating for science to be used as this sort of bridge?

Yangyang Cheng: I'm hesitant to paint it this way because the world was certainly much more divided then. And then again, the primary reason for that was because of the nature of the Soviet Union, and also China then as well. It was the government's own policies that forbade Chinese nationals to travel overseas.

At a time when the world was structurally divided, there were some of these channels being pushed open by some very brave individuals. The world is not like that today.

It is a lot more integrated in terms of science and technology, education, and commerce in particular.

We can think about Operation Paperclip, where the US government recruited large numbers of former Nazi scientists and brought them to the US.

They were people who were members of the Nazi party and had fought for Germany - not necessarily in the trenches, but they had contributed to the effort - and would not pass immigration scrutiny. But they were scientists or engineers and had these particular skills the US found helpful in its Cold War with the Soviet Union.

And so officials would put a paperclip on their immigration files to mark these individuals and help them pass through security screenings. Of course, the most notable alumni of this was Werner Von Braun, who was later instrumental in the US space program.

I think there is an issue of nations and national governments trying to appropriate science and use that as a tool of state power. That is really not new and it is always inherently dangerous.

And what I do worry about now is that the kind of rhetoric from both the United States and China really sounds quite similar.

There are linguistics that are a bit different, but they really sound quite similar in terms of national competition, national power, science and technology and national leadership.

I can understand how politicians may say that it’s because of the constraints of their role, but it's something that I do think civil society, academia and the scientific community have an obligation to reflect on and at times to push back against. It is a very dangerous mindset to think that the problem is not bombs, but whose bomb.

And that comes back to what I mentioned at the very beginning, right? Judith Butler posed the question of what makes for a grievable life. If bombs and weapons kill people and if the people are equally grievable and possess as much humanity [as each other]... If we come from that starting point and then use that to evaluate how science and technology is being used and how scientists conduct their work, I think that that is a much more responsible standpoint.

Otherwise, if we cling to a national framework, it is inherently exclusionary, logically inconsistent and intellectually dishonest.

Alex Liang: Going back to the rhetoric that we use and the terminology that we use. You were talking about the “new red scare” and you broke down each word of it that you took issue with. Are there other words in the discourse that you have issues with or terminology that we use? and I'm thinking here things like “ chilling effect” or “brain drain.”

Yangyang Cheng: I would acknowledge that a lot of people who use these words come from positions of good intentions, and that they are alarmed by this heightened scrutiny with a racialized tint.

I think “brain drain” is a terminology that I really dislike. It's also a really ugly term even just in terms of language, in terms of aesthetics. It's almost like a violent terminology, and that is at its core dehumanizing. I am not a brain, I'm a person.

There are two layers as to why a brain drain is problematic. The first is it has this connotation that somehow science and technology are instruments of state power and scientists are geopolitical state assets or some form of rare mineral. And then there are the countries where the US or China compete to extract more and create this form of hegemony over it.

That is a very parochial and indeed a very dangerous mindset.

It's not a good thing for one country to have a monopoly over any branch of science or any group of scientists.

It is actually diversity, including geographical diversity, that is important for the safe, ethical, responsible, sustainable development of science.

The second layer is that brain drain also enforces this idea of the “good immigrant”, and that again also enforces national borders and gives people a value or a score of who is desired and who is not by trading their degrees, their education, their skills, labor, or even their stories to purchase a ticket across a border.

If we believe fundamentally that migration is a human right and not a privilege, terminology like brain drain should be a fiercely resisted.

Jordan Schneider: Can you wash some of the ugliness of such phrases out with another and close this with a reading as well?

Yangyang Cheng: Yes. And since we were talking about science and technology and the use of borders, I thought I would read a few paragraphs from an essay I wrote for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists for their 75th anniversary issue. It was published last December.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, I should also mention, was founded by Manhattan Project scientists in the fall of 1945 when they were reckoning with the costs of their creation and on the critical relationships between science, scientists and state power. The title of the essay is “The edge of our existence: A particle physicist examines the architecture of society”.

“The coronavirus came from nature. It has no morals, no agenda or belief. Its presence among our species is a result of human activity, a reminder of our disruptive power and our ultimate vulnerability. No armies or weapons, material wealth or political borders can protect us from changes in the ecosystem. As we continue to expand our presence on Earth and exploit it for short-term gain, as more areas become uninhabitable due to flooding, drought, or fires, as melting glaciers and warming seas awaken ancient pathogens, what’s happened in 2020 is only a prelude to the much worse to come

“The face of our planet is shifting. We are all becoming displaced. It starts at the margins: The most vulnerable are the first to feel its impact. The way we respond to their plight will determine our own fate. If we cling to old ideas of citizenship and creed, if we use the pretense of scarcity to justify our bigotry, if we let migrants drown at sea and refugees languish in camps, it won’t be long until we realize that we too do not belong anywhere. If we are determined to shape our identity through the destruction of a collective other, we are only ensuring our mutual demise.

“The state of our humanity is not measured by the richest or the most powerful, nor can it be understood by listening only to those safely at the center. The border is not an edge but a new beginning. The ones who have persevered in the periphery hold the key to our future survival. Their presence disrupts our comfort, challenges our norms, uncovers the paucity of our moral imagination. Their voices, the forcibly silenced and deliberately unheard, enrich our vocabulary at a time when the enormity of the truth puts us at a loss for words. The liberation of the most oppressed will necessitate the destruction of all systems of oppression. The empowerment of the most disenfranchised will empower us all.”

Have thoughts, comments or ideas you want to share about this week’s ChinaTalk? Leave your feedback in the comments!

Thanks for reading,

Jordan