Semi Stories of the Year

"Industry wants to have their cake and eat it too. They want the subsidy, plus the ability to sell to China unconditionally."

Doug O'Laughlin of Fabricated Knowledge and Dylan Patel of SemiAnalysis recently came on ChinaTalk to discuss the most important semiconductor stories of the past year. We discuss:

the politicization of semiconductors

RISC-V’s rise

Samsung and Intel’s stumbles

Arm’s decision to take on Qualcomm

The Semi Cycle and Politicization

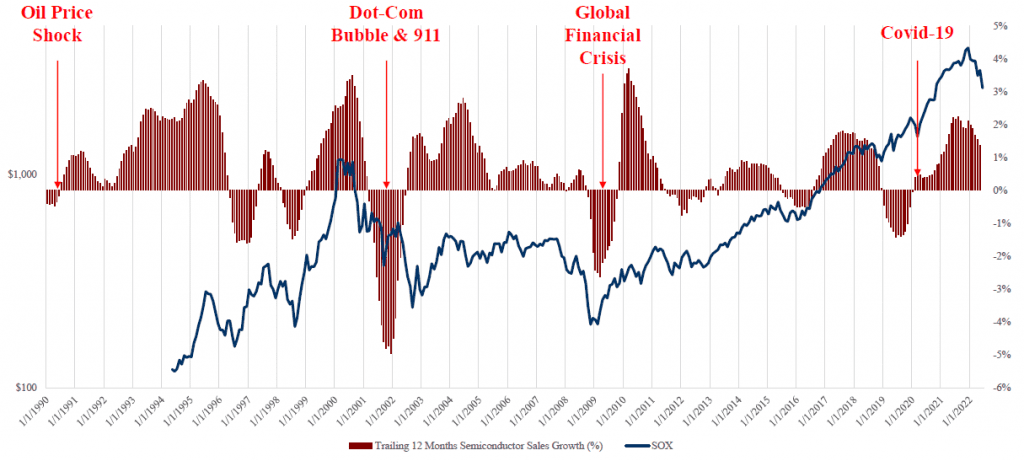

Doug O’Laughlin: This cycle is the realest one we've had since ’09 essentially. In ’09 the demand, the demand dynamics were much worse. We’re still in this will-they-won't-they of a global recession (or not), but this cycle has been really interesting and, obviously for me, the second biggest story of the year.

If you've been following the industry, the cycles have been getting better and better over time: less intense, less crazy, less massive over-inventory, less supply-driven… This cycle, on the upside, was almost beautiful in terms of demand: the ultimate upcycle. We're not having the ultimate downcycle — this is not the 1990s — but we are having a meaningful downcycle.

The fact that this cycle will probably be as intense as ’09 without anywhere near the end-market intense destruction makes the inventory cycle that we're currently going through the number two story of this year.

Dylan Patel: It went from shortage-shortage-shortage to surplus in the snap of a finger. Doug and I were screaming it for a little bit just because we follow the stocks and such, but I still [know] engineers in the industry that are like, “Oh, it's still a shortage.”

Jordan Schneider: In 2020, 2021, and even the first half of 2022, we had these enormous announcements of CapEx from major manufacturers around the world in both memory and logic. What's going to happen to those numbers in the coming years?

Doug O’Laughlin: They're going down. [With regards to] the CapEx that got delivered in 2020 and 2021, the supply is still coming online, and utilization, essentially, was at the highest it's ever been in the entire history of the semiconductor industry. So yes, the upcycle was really intense and it was longer than average as well. One of the things that are really interesting is if you look at the 2018 cycle in memory, it was really tepid and I think that many investors, myself included, had a belief that because of the memory oligopoly, things would be a little chiller from here. And now after two quarters of down 30% pricing, we're like, “Oh, this is still just as intense as it used to be.” I really feel like that has broken the belief of cyclicality getting a little better.

What's also weird is even right now — we're talking about an over-inventory — there are still segments of the industry that are in undersupply. I feel like the leading-edge aspect of this cycle was really interesting, where the leading edge became really sexy again, really needed, and underinvested. That is something that's definitely changed. For example, this entire inventory correction is mostly happening on the leading edge, but there is still some stuff in the lagging edge, like these really old hundred-nanometer chips that are just completely out of demand or out of supply, [that they] still can't get enough of.

Dylan Patel: Samsung is blowing up the memory oligopoly. Everyone else is cutting. Micron said, “We're going to cut our equipment by 50%.” SK hynix said similar stuff. And then Samsung goes and decides, “Ah, we're going to increase it.”

The politicization of the semiconductor industry means that there are subsidies and there is going to be spending. So it might not be down as much as we think.

Jordan Schneider: My grandfather was the publisher for a trade magazine Solid State Technology for the industry in the fifties and sixties. The family lore was that when the cycle was down, he would let all the US firms buy ads on loan — it got that bad. They would make him more than whole when the cycle turned.

Doug O’Laughlin: Forecasting is better now, to be clear. I have been doing a lot of history work this last year, just trying to get context of cycles. Man, some of the cycles back in the day, you're like, “What the hell is going on?” The ’97 cycle for memory was insane: I think they had a 70% drawdown and then another 20%, so memory pricing went down 85%. How do you plan a business on that? And while the pricing is going down, they're increasing supply the entire time. The context of history makes you appreciate how much better this is, but yes, it is still cyclical and it will probably always be still cyclical.

Economic Cold War?

Dylan Patel: I can only guess, but I think what finally got the US to be like, “Oh crap,” was the SMIC 7-nanometer. Maybe, if you look at the exact technical specifications, it's more like an eight, but it's really cool and amazing that they were able to achieve that. I think that might be what partially lit the fire of the CHIPS Act. One day, Chuck Schumer said SMIC achieved 7-nanometer on Capitol Hill.

Jordan Schneider: I think the SMIC 7-nanometer story was enormous, and there's also been reporting subsequent that this was something that really helped get the ball moving in the inner agency. With regards to export controls, you had the chip shortage, covid, supply chains in general…it was just something in the atmosphere that led voters and their representatives to be more amenable to this sort of stuff. Of course, you just had Taiwan tensions and the fear of something happening setting us back decades in terms of what our lives would look like without access to the Taiwanese semiconductor ecosystem. The salience of this risk woke a lot of people up as US-China relations really fell off over the past few years.

Dylan Patel: This is now, in my opinion, economic Cold War. It's the start of more and more escalation. The decoupling is real.

Maybe you could argue it started with Huawei, but now we’ve gone to, “China, you cannot have lithography tools, deposition tools, AI chips… Oh, by the way, this is everything that the economy's going to be.” That's my biggest takeaway from this year.

Jordan Schneider: We're recording this on December 15th, Yesterday, Reuters reported that China was considering a $132 billion subsidy program for its domestic ecosystem. [Bloomberg subsequently reported in January that Chinese officials were having second thoughts about the spending]. It's not like either side is going to be putting the knives away anytime soon because this is downstream of the political relationship, which is a function of where Xi has been, where he's likely to go (which is a) nowhere, and b) to dark places), and the response that you're seeing (both in the US and around the world) to the direction that Xi has led his country in the past decade. I'm pessimistic. BIS’ Alan Estevez in an interview late year, when asked by Martijn Rasser of CNAS whether they are considering doing this for other technologies, said, “Yeah, we meet every week talking about this.”

It's not just chips; it has the potential to spread to every “force-multiplying” technology that's going to be coming down the pipeline. We're also looking at elections in 2024 where this stuff could be turned up another notch by having a Republican in the White House.

Doug O’Laughlin: I think when we look back in history, we can definitely point to 2022 as being the year [that] the delineation between the supply chains [and] the thought process that both of these countries are going to have to have completely separate supply chains really all began.

They already have separate internets. In many ways, by not being able to even interact with each other directly, we've been pulling away from each other for a long time. I think that that is definitely the biggest story. It's bigger than semiconductors, but I feel like it percolated up through semiconductors.

You're talking about other industries; I think they're doing a call for essentially a CHIPS Act for the biopharma industry, which is another obviously huge force multiplier for the future. So this is just going to continue.

Jordan Schneider: I think more and more industries are going to try to play the cards that the semiconductor industry did, as Dylan said, with [saying], “Our thing is super strategic [and] it's going to change the world. You need to win the future? You need to win the thing that we're doing. So please give us a lot of money; don't make it too hard for us to sell to China, but this is the deal. And we're going to need to be compensated for the cut in market share that you're going to be inflicting on us.”

Doug O’Laughlin: American industries want to have their cake and eat it too. They want the subsidy, plus the ability to sell to China conditionally.

These are bitter pills to swallow because American industry interests are definitely always going to protect the profit pool. But that's just their incentive. Over a long enough period of time, it does feel like most of the business that is being done in China is at risk.

That's a big takeaway for me. I think if you're an investor thinking about investing in China, you should definitely consider how terrifying it is that we're doing economic war and cannon fodder is probably the financial flows between the two countries.

That's something I'm very cognizant of and thinking about often: if there is a linkage, it should be discounted, or maybe considered at risk, in any way, shape and form. That's just how this is going if we're doing economic war.

Next we get into:

Samsung and Intel’s stumbles

RISC-V’s rise

Arm’s decision to take on Qualcomm