Sen. Young on Tech Legislation (AI, Chips, Chevron, Civil Service)

How to keep tech innovation bipartisan

Where is Congress on AI? How will a second Trump term impact US innovation? Does Congress have what it takes to step up and legislate in a world without Chevron?

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed Senator Todd Young of Indiana (R). He’s a rare breed on Capitol Hill these days: an actual legislator. Sen. Young drafted the Chips and Science Act with Sen. Schumer and is the co-author of my personal favorite bill this Congress which aims to establish an Office of Global Competition Analysis. He announced earlier this year that he would not be endorsing Trump’s candidacy this cycle.

We get into…

Biden’s woes

The case for an office of tech net assessment

The future of tech legislation post-Chevron

The Senate’s AI Policy Roadmap and where the GOP is on AI regulation

Chinese espionage and high-skill immigration policy

Listen on Spotify by clicking below:

Biden 2024

Jordan Schneider: We’re recording this on the morning of July 10th. Senator Bennett – with whom you co-authored an excellent bill pushing forward an Office of Global Competition Analysis – went on TV last night saying that he didn’t think Biden could win. Do you have any reflections on what’s happening on the other side of the aisle right now?

Senator Todd Young: I tend to subscribe to the old adage that when your opponents are drowning, you generally don’t want to throw them a life ring. But it suffices to say, this is a sad situation. It really stems from the fact that the president seems to be declining in health, as we all do as we age. Unfortunately, too many people who are close to the president seem to have not been forthcoming — and that includes certain members of the media — about his health. In the near term, that gives me some concerns about our national security, but in the longer term, I think it’s fair for the American people to want more information so that they can make an assessment of his ability to lead going forward.

I do think that these questions are likely to continue, and this will be an ongoing narrative should he stay in the race, but, I don’t want to get into play and pundit. This is a sad situation and the American people deserve better.

AI on the Hill

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start by discussing the Office of Global Competition Analysis. I’d love to hear you reflect on how policymakers got up to speed on semiconductors and how they’re coming up the curve on AI.

What information inputs do legislators receive today around emerging technology and what structural changes do you think the country needs in order to improve that information flow?

Senator Todd Young: The way I gathered information on our semiconductor tech and production gap with other countries, was by talking to certain members of the national security community, who happened to be at some social gatherings I was attending. I heard our precarious situation referenced in a classified setting when we were having a briefing from some military, officials and administration leaders. But there was no systematic way for me to assess the precarity of our technological advancement and our, military, capacity to produce semiconductors and certainly no way for me to compare in a rigorous way, our ability to produce these semiconductors, how important they were, and how other countries were doing.

There was no office of net assessment for us to assess our strength versus the strength of certain adversaries. That’s what we need. That’s what the legislation that Senator Bennett and I have coauthored would provide.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss the overruling of Chevron. In her dissenting opinion, Justice Kagan specifically pointed to AI as the sort of thing that would be really difficult to legislate in a post-Chevron world.

Why are legislators reluctant to give their staffers raises and hire more of them and bring back the OTA? What gives?

Senator Todd Young: Members of Congress believe that those expenditures are unnecessary. I don’t. There will be things that we champion and advance in this generation that in retrospect will be regarded as misguided.

It was misguided to eliminate the OTA as a modest expenditure. It helped members of Congress make smart decisions about technology. There are ways that in my own office, we’ve been able to augment our team. We brought on some scientists and technical experts to interface with the experts, but I think every member of Congress needs that kind of expertise at the ready.

Let me step back from the question you’re getting at here, which is, with the Chevron doctrine, Sotomayor’s, I think, lamentation that, the government will be unable to adjust policymaking nimbly enough as we learn more things about emerging technologies like AI – I think that’s a fair concern, frankly.

I supported overturning the Chevron doctrine because I think government has grown too distended, too out of touch with the concerns and sometimes the values of the people I represent. But there is a risk here. Congress now needs to fill in the gaps, legislate, and watch for major changes in society that require quick adjustments.

How will we do this? I’ve thought about this. We need to embed, within our federal government, a lot more expertise than we currently have as it relates to AI innovations and AI capabilities. These individuals need to be in touch with members of Congress when there are gaps in our laws. Members of Congress, in turn, need to do their oversight duties, better than they have in the last number of decades.

I’m on the Commerce Committee. Right now, I’m not as incentivized to get to know people within the executive branch at the Department of Commerce who have expertise in these different verticals. But we’re going to have to do that more, hold more oversight hearings, and work with the experts working in government agencies to figure out where the policymaking gaps are.

No doubt about it, this is going to require members of Congress not just to lament the state of things and appear on television – but actually to legislate when required and, yeah, it’s our time to put up or shut up.

Jordan Schneider: We only let the adults in the room on ChinaTalk, and you’re one of them, but a lot of your colleagues aren’t. Do you have any structural solutions for changing the incentives to get folks actually focused and excited about legislating again?

Senator Todd Young: Yeah, I do. We need to increase the quality of technical experts in every agency of government. You do that by changing how much you can compensate people in government. In part, we propose more flexibility in government hiring so you can get those AI experts on board. That will also help with retention.

Some agencies have long done this very well. For example, the Food and Drug Administration is broadly respected. There are some challenges that our pharma, bio, and food companies have with the FDA, but generally it’s a pretty well-respected agency. The Department of the Treasury is also able to attract and retain quite a bit of talent.

We need to do that with other agencies, but I’d say with respect to my colleagues, that’s really where the incentives come in. The number one incentive is the ability to shape these things and not have your handiwork overridden by the agencies.

Next, since Chevron has been overturned, it’s pretty clear that you can’t pass vague laws and leave it to the administrations to figure out the rest. You’re actually going to be incentivized through the law to fill in the messy details of legislation. That requires a lot of work. I know because my legislative efforts actually do fill in the details. To try and Get 60 votes in the United States Senate, which by definition is a bipartisan effort, is oftentimes very challenging and unglamorous. But we will be held accountable for failing to do so. Those incentives will kick in and we’ll respond to them as human beings do.

Jordan Schneider: You pointed to this idea of civil service reform, which I am worried is going to very quickly become a partisan thing in a Trump administration – they’re already talking about their version of civil service reform. Any ideas about how to pick this up in a bipartisan way in 2025?

Senator Todd Young: This is a tough one. This is admittedly a very tough one. On one hand, you're right. Civil service reform, almost in any form it takes, I think most people would agree, it would become a partisan exercise. But to do nothing is also partisan, in a sense, right? The Democratic Party tilt to our civil service, or at least the Democratic Party tilt to large unions, including government unions, it’s pretty apparent to me. I think what we need to do is step back and say, all right, what does good policymaking dictate? Should we make some changes to how our civil service, operates? I think it’s entirely fair for us to open up this Pandora’s box and try to engage in some necessary and responsible policy changes.

I’m not on this particular committee. That may be a blessing because this would be quite the fight, but generally the decision to take a look at how we hire, fire, and hold accountable government employees, and what sort of responsibilities they should have is an essential function of our Board of Directors or Members of Congress.

Jordan Schneider: You pointed to two places that have a reputation for really good talent. The CHIPS Act program office is another, and part of the way they were able to do that is to basically have it written into the legislation that they didn’t have to follow the rules.

Senator Todd Young: Not to quibble, but they had to follow a different set of rules.

But you are right. Because if you look at the performance of the CHIPS program office, it’s starting to receive rave reviews, even from those who are highly skeptical of the broader CHIPS and science effort. But the performance suggests that maybe we should extend this kind of different framework to other areas of government.

I think that’s an appropriate conclusion.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s stay on the CHIPS Act. Aside from ducking my interview requests, CPO gets full marks from me and everyone else who isn’t over-indexing on childcare requirements.

I want to talk about the science part of the CHIPS and Science Act. You’ve spoken in the past about the idea of R&D funding as a national competitiveness imperative. That’s been resonating, but ultimately not enough to get the funding.

Do you have any thoughts on the future of those appropriations? What’s changed over the past year or two that led to the underfunding of the NSF and similar organizations?

Senator Todd Young: The prioritization of funding for the science portion has mostly fallen on partisan political lines, with Democrats being supportive of more R&D funding and the science portion of the funding, and Republicans being more skeptical.

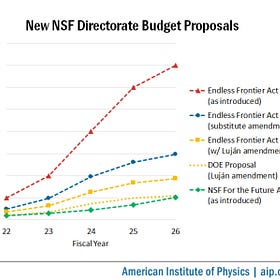

I’ve been one of a handful of Republicans who have been vocally supportive of course, being a coauthor of the broader effort, but – this should not be a partisan effort. I authored the Endless Frontier Act, which is the science portion of CHIPS and Science, years before the Chips and Science Act passed with Chuck Schumer. That effort began during the Trump years and we were working with some high-placed individuals in the Trump State Department.

What we saw beginning in the Eisenhower years was a massive increase in federal research investment through our research universities and DOE labs. We were able to win the space race in the subsequent decades. We saw amazing growth in aerospace and many other sectors on account of that seed corn investment through our national research enterprise. But the trend lines began to change in the ‘90s and the 2000s.

Though the benefit-to-cost ratio of research investments is off the charts, we’ve seen we saw the percentage of research applications go down just because the resources to fund them were drying up. Those are lost economic opportunities, for our entire economy.

As our fiscal situation has deteriorated, there’s naturally been a desire to pull back from a number of investments, but I would remind a number of my fellow green eyeshade legislators out there that the real number we should be looking at as we think about our fiscal deterioration is the debt-to-GDP ratio.

It’s a fraction — debt/GDP. You can’t starve your economy of one of the components of your GDP, which is R&D investment, in order to deal with the debt.

Let’s grow the denominator while we try and control the numerator as well. That’s how I look at it.

Going forward, will things change?

There’s a real opportunity to remind the Trump administration that they can take credit for this reinvigoration of the research enterprise. The genesis of this idea was in part a function of my interaction with the Trump administration. Let’s make America grow again, right?

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, I remember those heady days of a hundred-billion-dollar Endless Frontier.

Endless Frontier Neutered!

Yesterday I published an Emergency ChinaTalk podcast with Sam Hammond of the Niskanen Center on the butchering of the Endless Frontier Act over the past week. It’s one thing to not like the Tech Directorate (more context in last week’s edition, this was initially going to get $100bn over 5 years and now is a rounding error in this bill), but the Senate …

Senator Todd Young: We had the Endless Frontier Act, and then you had US Innovation and Competition Act (USECA), and then we had CHIPS, and then we had CHIPS Plus, and then we had CHIPS and Science. We went through a lot of iterations. The marketing department worked overtime there.

Jordan Schneider: Speaking of spending lots of money, let’s talk about the AI policy roadmap, which advocates for spending tens of billions of dollars on AI innovation each year. Where did that price tag come from, and what will the government spend that money on?

Senator Todd Young: I don’t think the government’s going to have to spend a lot of money, except for on some fundamental research. This is one of the categories of government spending that the likes of Milton Friedman and so many others embraced. Spending money on a public good is something that’s been broadly supported in my own party. We found bipartisan support for it through this AI roadmap development, including myself, Chuck Schumer, Mike Rounds, and Martin Heinrich.

Is that a lot of money? Yes, it’s a lot of money and we need to get more clarity for members on exactly what this money would be spent on. But where did this amount of tens of billions of dollars in government research on AI come from? It came from the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. This was a group of experts, co-chairs were Eric Schmidt, formerly of Google, and Robert Work, long time Pentagon luminary and leader. They recommended that figure.

We embraced it because we had heard from the best minds in the world – from Zuckerberg to Gates to our Pentagon officials and many others – that it made a lot of sense.

But beyond that, I don’t think much money is going to have to be spent. We’re going to have to change how we spend some of our money on education and the workforce in this country and make sure that every American is literate in artificial intelligence and is ready for an AI-enabled world.

The main challenge of preparing for this AI-enabled world is going to be one of adapting our existing laws – whether through statute or court-made law through precedent – which hopefully reflect our standards on privacy and consumer protection. Sometimes that will require legislative fixes, and that needs to be handled as it’s always handled through committees of jurisdiction. Occasionally, they can be adjusted even in this post-Chevron environment through regulatory action.

But here again, this invites members of Congress to do their job, as this technology rapidly changes our society and our lives, mostly in a positive way.

The GOP Platform on Tech and Immigration

Jordan Schneider: You’ve been a strong supporter of NIST and the AI Safety Institute. I’d like to read you a line from the GOP party platform, if I may.

We will repeal Joe Biden’s dangerous Executive Order that hinders AI Innovation, and imposes Radical Leftwing ideas on the development of this technology.

That kind of seems like killing the AI safety institute. What’s the case you’d make to your fellow party members to convince them that the work NIST is doing is valuable and important for the country?

Senator Todd Young: I know some people are on the platform committee, and there are parts of this GOP platform that I think are really important. Our party came together on some provisions related to life and marriage, for example.

But, I also know that sometimes these things are developed by 22-year-old interns, and they got the AI portfolio because they knew how to operate the latest version of ChatGPT. I am not reading too much into that. It was vague, it was populistic, and it was not of great concern to me.

What I’m more interested in is my interaction with certain, former and probably future Trump administration officials, who are really excited about the possibilities of artificial intelligence, but recognize that we need some responsible regulatory structure. They acknowledge that some of the things in the Biden executive order were quite wise and need to be put into law to be given some permanence.

Other things are not perfect. It’s going to have to be revisited, which is natural in these early stages. Then in Congress, at least so far, the issue of artificial intelligence and lawmaking around it, has not grown particularly partisan. In fact, if you look at that document, two conservative Republicans and two liberal Democrats put that together and we were able to come together on a whole range of issues.

I think you’re going to see mostly continuity and evolution of policymaking between administrations, but naturally, there will probably be some changes as well.

Jordan Schneider: Trump proposed no tax on tips, and the next day we had bills in the House and the Senate to do that. He also went on a podcast and talked about stapling green cards to PhDs, but I haven’t seen any bills on that idea. What gives here? Where are we on high-skilled immigration?

Senator Todd Young: The more the merrier! That’s where I am. If we can train some of the world’s best talent and help endow them with amazing potential to add value to economies and improve lives – why wouldn’t we want to reap the fruit of our harvest? “You can stay here. You can stay here for a few years and, employ our people, innovate, spend a bunch of money, and lift our economy.”

I think we can do two things at once. We can control our border, we can rationalize our legal immigration system, and we can admit there are certain categories of workers where we need more. We need more rich people. We need more smart people. We need more people with amazing ideas and potential to improve our lives, and they’re graduates of our universities. I’m all in for that.

Of course, we’ve got to secure the border, Most everyone now agrees with that. I think the Biden, administration only started agreeing a couple of months ago, when it began to hurt them politically, which is unfortunate,

Jordan Schneider: We’ve talked a lot about the “promote” side of the ledger – on the “protect” side of AI and semiconductors, we have compute, we have data, we have algorithms.

Do you have strong opinions about where and how the US should be decoupling from China when it comes to artificial intelligence?

Senator Todd Young: I think we need to rebalance. Some of our colleges, I think Purdue University in my home state has done a very good job of rebalancing who we train to program these artificial intelligence models. That’s one thing we have to do with respect to the algorithm piece.

With respect to compute, again, we need to be thinking about workforce issues and if we can rebalance away from Chinese nationals – just to be direct about it – toward India and other large economy countries that want to send more students over here. We should be doing that – rewarding very good behavior. But we should invite foreign capital, foreign businesses in.

If you think about the third leg of the stool, we have to unlock more data and continue to invest in research. To the extent we can produce synthetic data to train these models, that’s going to be a force multiplier.

State capitalist economies – China and Russia and such – can take the health and genetic data of their entire populations without having any moral qualms or legal obstacles. That produces a lot of data. We’re really going to have to up our game in terms of making sure that we’re able to unlock more data and put it into formats that can be used to train these models.

This is where Congress definitely is going to have a role to make sure that there are secure and clear property rights around data, so developers will know what they can use and what they cannot use to train models.

Jordan Schneider: Interestingly, in that Trump interview I referenced, the interviewers were tiptoeing around by saying, “We need more high-skilled immigrants from India and Europe,” and Trump actually went off and said, “And China too.”

But we also have this GOP platform that says Republicans “Will use existing federal law to keep Christian-hating communists, Marxists, and socialists out of America.”

Just to push back a little bit, Senator – I don’t want to liken this to, say, the Chinese Exclusion Act – but there is something tricky and very uncomfortable about you saying that one nationality is preferred over others when we’re talking about people who want to live and settle and bring their lives here, right?

Senator Todd Young: Yeah, and it’s uncomfortable for me to say it as well. There’s a thoughtful counter. The fact that it’s uncomfortable for you or me doesn't mean we shouldn’t talk about it. Otherwise, we get into sort of like safe spaces, and that would not lead to very good decision-making or lowercase-l liberal democratic dialogue.

The challenge is that we’re dealing with dual-use technologies here. The artificial intelligence solutions that are used to help us choose an optimized grocery list are quite similar in how they operate to some of the AI technologies that help you make better decisions on a battlefield.

That’s the challenge. Are you training people who operate within a system that will allow the People’s Liberation Army to improve their capabilities over a period of time. I think that's the sort of hardnosed consideration we're supposed to have.

Now, there’s a competing view here, and it’s a bit in tension with what I've just laid out, and I’m still struggling, admittedly, to reconcile it – and that is, “Wait, what about the opportunity for brain drain out of China?”

But then the counterpoint will be made, thoughtfully, “Isn’t there leakage from that brain drain out of China, into the United States?” Leakage meaning espionage. You have to concede there’s a fair amount of espionage, very difficult to quantify. These are the moral dilemmas that were put in, not because I just decided to go there, but because this horrific regime in Beijing put us in these moral dilemmas.

If we have a limited number of resources to invest in education – we want to continue to invite foreign nationals for all kinds of reasons. In part because it subsidizes tuition for our own students, in part because they add value to the economy, they build better relations with the world and so forth.

If you have two equally merited students, one from India and one from China, should you give a little favor to the country that is more cooperative with us?

India may not always be the best example, right? Just this week, we saw Modi, palling around with, Putin – but at least they’re on-side as it relates to the broader competition between us and China.

I wanted to elaborate because it’s very easy for those who aren’t thinking about the entire picture to just shy away from this conversation because – think of the border security challenge. The Biden administration, for the better part of three and a half years, refused to secure our southern border because they didn't want to be called racist. That’s my reading. That’s a good illustration of what failing to adapt to the times can lead to.

Jordan Schneider: There were a whole lot of foreign nationals who were working on the Manhattan Project, and part of the reason the West won World War II was because we got the better Germans. It’s not an impossible square to circle, and I agree with you that you can’t just refuse to talk about issues of espionage.

Senator Todd Young: How many individuals was that? How many foreign nationals were on the Manhattan Project? Enough to monitor, right?

Jordan Schneider: The total number of people working on the project was like 130,000. But yes, the core group in Los Alamos is different than a broad innovation ecosystem.

But I guess the ultimate question is this: is the dominant strategy running faster, or ensuring that your secrets don’t leak no matter the cost? Ultimately there is some sort of trade-off there, right?

Senator Todd Young: There’s absolutely a trade-off. We would all agree, and this is where we’ve ended up on policymaking so far, that there are certain types of research that are so sensitive on account of their national security implications that you have to really be scrutinized before you can participate.

Through the CHIPS and Science Act, we were actually able to raise the standard, which I think was, broadly agreed to be an appropriate countermeasure to some of the leakage that’s occurred. But still, we’ve had far too much, and I think this will be an ongoing, debate, and candidly, though I landed on one side of the line, I’m open to counter-argument.

But what I won’t do is embrace a particular position because it feels uncomfortable. Instead, what I’ll do is embrace a position based on what is in the national security interest and broader interest of my constituents.

Jordan Schneider: Senator Young, we end every episode with a song. Do you have one that captures the energy of your tech policymaking?

Senator Todd Young: Ha! Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap – AC/DC.

Very good interview. I was not expecting that song LOL