Are politicians and actors two sides of the same coin? Can you become a better public speaker by studying soliloquies? What can Shakespeare teach us about the nature of power?

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed Eliot Cohen: SAIS professor, military historian, and counselor to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. He is also the author of The Hollow Crown: Shakespeare on How Leaders Rise, Rule, and Fall.

Co-hosting is Jordan’s little brother, actor Phil Schneider. He recently graduated from Yale where he starred in a production of Hamlet. He’s played Romeo, Octavius Valentine, Richard II, and Leontes. Also, he’s looking for a new agent + advice about navigating showbusiness — please reach out at jordan@chinatalk.media to connect!

We discuss:

Royal/executive power — what getting it does to you, and why relinquishing it is so hard;

Court intrigues of yore (and today);

Timeless techniques for exhorting and manipulating the masses;

What makes a great speech;

What it really means to be an effective leader, and how great leaders know when it's time to quit.

I’m heading to Oslo in two weeks! If you live in Norway and/or have reading recs, please reach out.

The Cost of Power

Jordan Schneider: Let’s kick it off with a passage. Eliot, why don’t you give us some context on the Hollow Crown speech?

Eliot Cohen: The Hollow Crown speech is given by Richard II, who’s one of the more feeble kings in Shakespeare, although he is brilliantly fluent.

He’s actually very smart, but he ends up deposed and comes to a sticky end. Here, he’s been deposed — and this is a guy who’d been obsessed with being king — and he delivers this soliloquy…

Phil Schneider:

For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings;

How some have been deposed; some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed;

Some poison’d by their wives: some sleeping kill’d;

All murder’d: for within the hollow crown

That rounds the mortal temples of a king

Keeps Death his court and there the antic sits,

Scoffing his state and grinning at his pomp,

Allowing him a breath, a little scene,

To monarchize, be fear’d and kill with looks,

Infusing him with self and vain conceit,

As if this flesh which walls about our life,

Were brass impregnable, and humour’d thus

Comes at the last and with a little pin

Bores through his castle wall, and farewell king!

Cover your heads and mock not flesh and blood

With solemn reverence: throw away respect,

Tradition, form and ceremonious duty,

For you have but mistook me all this while:

I live with bread like you, feel want,

Taste grief, need friends: subjected thus,

How can you say to me, I am a king?

Eliot Cohen: That is wonderful. I have to tell you: I’ve been doing a whole bunch of podcasts about this book, and it usually falls upon me, and I am not a tenth as good as Phil. Bravo.

Let me just say a few things about that speech. I think one of the more poignant things about it is where he says, I need friends. One of the things that’s so striking about him as a character — striking about Shakespeare’s kings in general, but that I would argue is quite characteristic of most people at the top — is that it’s very hard for them to have friends. Some of them lose the capacity for friendship.

One of the great themes, I argue in this book, is that Shakespeare shows how the exercise of power over a long period of time can really strip away your humanity.

One of the things I talk about in the book in terms of Shakespeare’s technique is that he often uses what the Greeks called anagnorisis. That’s when somebody says, “Oh, that’s what’s happening,” or, “Oh, that’s who I really am.” There’s a great moment in Henry VIII where that happens. The person who’s speaking is Cardinal Wolsey. He has been, in effect, Henry VII’s Prime Minister. He’s from very humble origins, the son of a butcher. He rises up in the church, becomes a cardinal, extremely powerful, and then he is suddenly deposed.

And this is what he says.

Phil Schneider:

Farewell! a long farewell, to all my greatness!

This is the state of man: to-day he puts forth

The tender leaves of hope, to-morrow blossoms,

And bears his blushing honours thick upon him:

The third day comes a frost, a killing frost,

And,—when he thinks, good easy man, full surely

His greatness is a-ripening,—nips his root,

And then he falls, as I do. I have ventured,

Like little wanton boys that swim on bladders,

This many summers in a sea of glory,

But far beyond my depth: my high-blown pride

At length broke under me, and now has left me

Weary, and old with service, to the mercy

Of a rude stream, that must for ever hide me.

Eliot Cohen: What’s happened there is that Wolsey undergoes anagnorisis. “This is who I am.” He’s been swimming on a sea of glory, but far beyond his depth, and — pop, the inflated bladder that he’s been clinging to goes, and down he goes. I remember when I heard that speech — I said, “Oh my goodness, I know that guy.” If you live in Washington, you do know that guy.

It’s a device that Shakespeare uses: this moment where somebody’s facing the truth. What’s fascinating to me is that there are occasions when life mirrors art rather than the other way around.

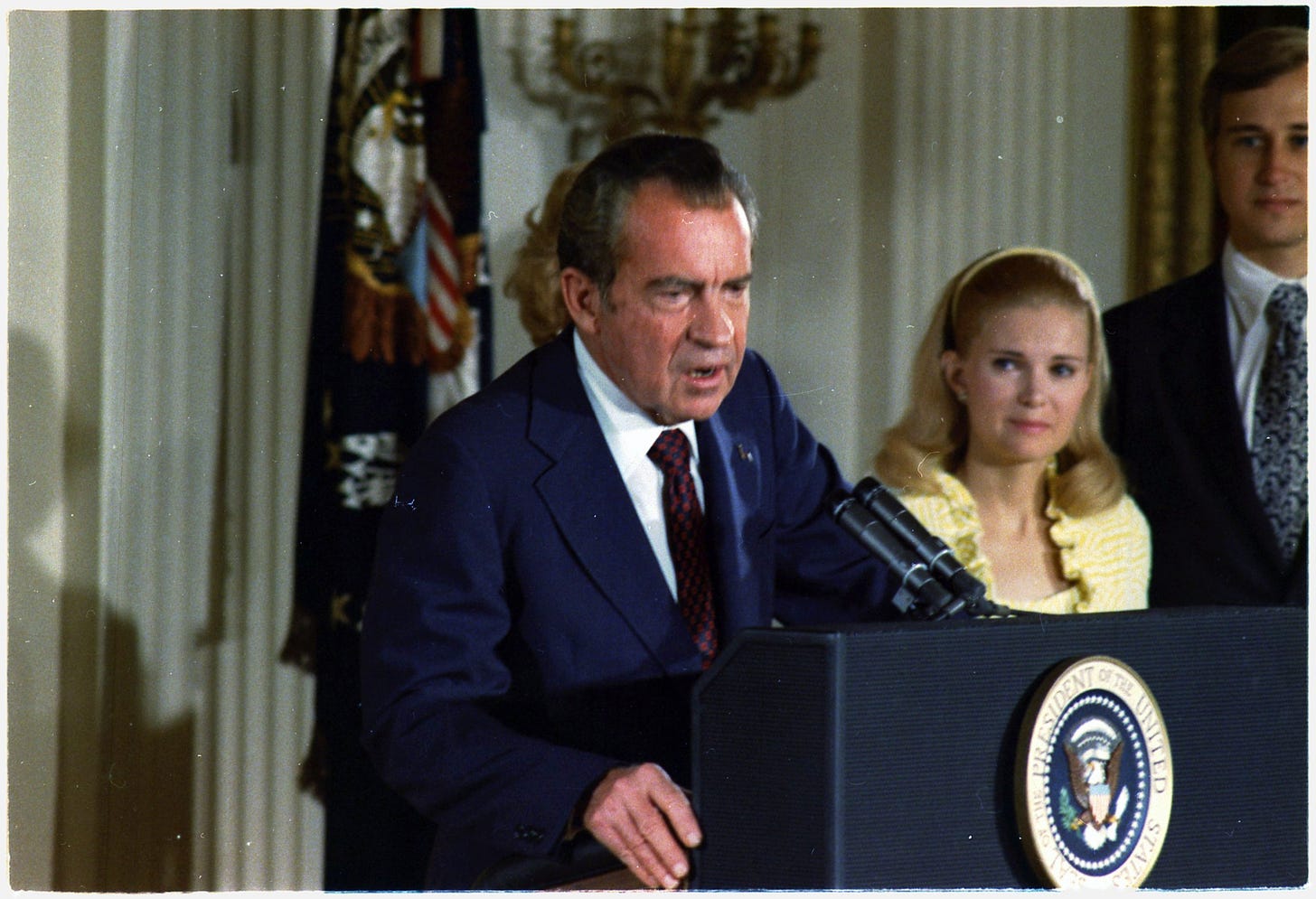

You could say that Richard Nixon’s farewell to his staff was a moment of anagnorisis — where he suddenly realized who he was, what he had done. The tape that you’ll be hearing is a speech to his staff just before he leaves the White House after having resigned the Presidency. On the one hand he’s talking to them, but in another way, like Wolsey, he’s also talking to himself. Here’s a quote from the recording:

We think that when we lose an election, we think that when we suffer a defeat, that all is ended. We think, as TR said, that the light had left his life forever. Not true. It’s only a beginning, always. The young must know it, the old must know it. It must always sustain us, because the greatness comes, not when things go always good for you, but the greatness comes, and you’re really tested, when you take some knocks, some disappointments, when sadness comes. Because only if you’ve been in the deepest valley, can you ever know how magnificent it is to be on the highest mountain. And so, I say to you on this occasion: we leave. We leave proud of the people who have stood by us and worked for us and served us and served this country. We want you to be proud of what you’ve done. We want you to continue to serve in government if that is your wish. Always give your best, never get discouraged, never be petty. Always remember: others may hate you, but those who hate you don’t win unless you hate them. And then you destroy yourself.

Jordan Schneider: I’d encourage folks to check out the recording on YouTube, because watching Nixon’s face as he tries to grapple with what’s happening — you see him opening and then closing, and then the final image that you’re left with is as he’s walking off the stage with a thumbs-up in his head as if it was a campaign rally. It’s this very small moment where he thinks, “Everyone in here whose life I just have completely ruined — not only to mention my own — these people who are supposed to be my friends who I’ve brought up and taken to the heights of power … I screwed it up for everyone.” It’s such a powerful, theatrical moment in American history.

I recently did an episode with Matt Pottinger, who left the Trump Administration on January 6 as Deputy National Security Advisor. Here’s a relevant quote:

Jordan Schneider: Usually when NSC staffers end up in books, it’s not in a particularly positive light — but you’ve had so many nice things written about you! Is there like a secret you can tell everyone, all the PR folks or people living in the bureaucracy?

Matt Pottinger: No, I’ve had my share of pretty nasty stuff written as well. I haven’t weighed the negative to the positive. … I believe that it’s good for people to want to serve in those jobs. I’m very proud of my service on the NSC staff. I’m proud of what we got done. I am proud of my colleagues that I worked with. I worked very hard to try to maintain a good working relationship with a pretty broad range of people.

Jordan Schneider: Nixon’s big swing, his big takeaway at the end of that speech is: you should all be proud of the work that you did. It was so funny watching that bubble out of Matt Pottinger’s subconscious, as someone who clearly left after January 6, testified to the Committee, has some mixed emotions. It must be very difficult for these people to reflect on the height of their power and greatness. Clearly there are things that they regret, but that’s not a face you really want to externalize or have to live with for the rest of your life.

Eliot Cohen: It’s something you wrestle with when you’re high up in government. I was the counselor of the Department of State in the last two years of the Bush administration. I was one of the most senior officials in the State Department, deeply involved in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, both of which I supported.

Even when you’re not working for somebody who’s monstrous like Trump or deeply problematic like Nixon, you wrestle with your conscience all the time, because the things you’re doing have real consequences and may be things that you deeply disapprove of.

Yet you do them and try to figure out: where do I draw the line? The advice which I’ve always given to people going in — which I followed myself — is you should always have your letter of resignation signed but undated, and you keep it in your desk drawer.

People wrestle with those things — and this is maybe a little bit far from Shakespeare, but I think the way you get through it with your character intact is being able to take pride in the actual work you are doing. Then you can get through it. If your sense of value is because “I was close to the President or the Secretary of State,” then you’ve got a problem.

I do think Shakespeare shows you how people who define the worth of what they’re doing in terms of their closeness to the most powerful person, or their own status are the ones who get themselves into moral trouble. I know Matt Pottinger and would count him as a friend. I know how he had to wrestle with what he did, and I give him credit for coming up with it. It was hard.

The one thing you didn’t mention in your introduction, Jordan, was that I was a dean, which is a reasonably powerful position at Hopkins.

Anytime you’re in a reasonably powerful position where you’re exercising power over other people, you are in constant moral jeopardy. You need to understand that, and in a way, you need to be on guard about it. And not everybody is.

Power — In and Off the Court

Jordan Schneider: Eliot, let’s talk about the idea of a court and why it is so enticing.

Eliot Cohen: When you think about the kind of politics that Shakespeare’s interested in and the kind of power that he’s interested in, a large part of it (not all of it — this doesn’t quite apply to his plays about ancient Rome, for example), is about the politics of the court and who’s the crown prince, who are the courtiers, who’s the consort, who’s the usurper. People might say, “Okay, fine, that’s in the era of Elizabethan and kings and queens, or Tudor kings and queens.”

But the important thing for everybody to understand — and that I think anybody who’s been in a serious hierarchical organization understands — is that at the top it is a court.

It’s a court if you are the president. In the State Department, I was a member of Condie Rice’s court. As a dean, I was a member of the court of the president of the University, Ron Daniels. You see court-like dynamics everywhere, and that’s one of the things that’s so brilliant about Shakespeare: he gets you thinking about how that works and who the different characters are in any court.

If you’re thinking about staff, the way to get into it is actually through a set of plays which are not that often performed and not that often read: the Henry VI plays. Henry VI is the son of Henry V, the heroic king who gives the famous Saint Crispin’s Day speech. He becomes king as an infant, and then there are three plays where England is basically torn apart by civil war. A large portion of those plays are about court politics. At the very beginning of Henry VI, his corpse is lying out there and his immediate subordinates suddenly begin fighting over what’s going to happen next, and you see that the kingdom is about to fall apart. Phil, do you have access to Henry VI?

Phil Schneider:

Each hath his place and function to attend:

I am left out; for me nothing remains.

But long I will not be Jack out of office:

The king from Eltham I intend to steal

And sit at chiefest stern of public weal.

Eliot Cohen: So, here we have a conniving courtier. I think if I opened a bar in Washington, I would call it “Jack Out of Office,” in honor of the Bishop of Winchester. Right there you see what’s happened to a court that’s become corrupted under Henry V. They’re getting this terrible news that all these lands that Henry IV had conquered in France have fallen to the French. They’re all running around. They all want to get glory and go out there and try to win it back, and this guy is plotting and conniving. Shakespeare spends a lot of his time with the different courtiers who surround a powerful person, and there’s a lot of this kind of behavior.

My brother Phil is looking for a new agent + advice about navigating showbusiness — please reach out at jordan@chinatalk.media to connect!

Power and the Masses, from Caesar to Trump

Jordan Schneider: We’ve done a little bit on the court — now let’s do some politics of the street! Probably the most famous speech, which we’re going to get a version of from Phil, is Mark Antony’s: after Caesar’s death, he’s riling up the masses to punish Brutus for his dastardly deeds.

Phil Schneider:

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears;

I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.

The evil that men do lives after them;

The good is oft interred with their bones;

So let it be with Caesar. The noble Brutus

Hath told you Caesar was ambitious:

If it were so, it was a grievous fault,

And grievously hath Caesar answer’d it.

Here, under leave of Brutus and the rest–

For Brutus is an honourable man;

So are they all, all honourable men–

Come I to speak in Caesar’s funeral.

He was my friend, faithful and just to me:

But Brutus says he was ambitious;

And Brutus is an honourable man.

He hath brought many captives home to Rome

Whose ransoms did the general coffers fill:

Did this in Caesar seem ambitious?

When that the poor have cried, Caesar hath wept:

Ambition should be made of sterner stuff:

Yet Brutus says he was ambitious;

And Brutus is an honourable man.

You all did see that on the Lupercal

I thrice presented him a kingly crown,

Which he did thrice refuse: was this ambition?

Yet Brutus says he was ambitious;

And, sure, he is an honourable man.

I speak not to disprove what Brutus spoke,

But here I am to speak what I do know.

You all did love him once, not without cause:

What cause withholds you then, to mourn for him?

O judgment! thou art fled to brutish beasts,

And men have lost their reason. Bear with me;

My heart is in the coffin there with Caesar,

And I must pause till it come back to me.

Eliot Cohen: You know, there are a number of wonderful things about that speech — and they really came through in your rendition of it, Phil.

Antony is brilliant at riling up the crowd. This continued repetition — “Brutus is an honorable man” — is actually the thing that initially allowed the conspirators to murder Caesar and the crowd to initially think, “Okay, maybe this was the right thing to do, because Brutus is such an honorable guy.” But of course, what he does is subtly undermine that by getting emotional and choked-up — whereas if you read Brutus’ speech when they came in, he just botches it completely. He only talks about himself and what an honorable fellow he is, and then he leaves and lets Mark Antony do that. Whereas Antony puts on this show of emotion and uses the body as a prop later on, where he says, “Here, I can show you all the different wounds. This was made by this guy, this guy, this guy.” And then of course, famously, the unkindest cut of all from Brutus. Antony is clearly trying to whip them up, and in some ways it feels like cynical manipulation.

Phil, just give us the very last line, when they go off, and they are rioting, and war has broken out in Rome.

Phil Schneider:

Now let it work! Mischief, thou art afoot,

Take thou what course thou wilt.

Eliot Cohen: He knows what he’s doing. The other interesting thing is that Shakespeare also makes it clear that Antony’s grief for Caesar, who had been his mentor and benefactor and patron, is sincere.

I think this is a very important point: one of the big things that Shakespeare can teach us is empathy, including with people we really don’t like or we mistrust. Empathy means being able to understand that the person on the other side is a complicated human being, and that they can have different things going on simultaneously.

From one angle, if you look at that speech, you could say, “This is contrived, this is calculated — all he’s trying to do is whip up an angry mob and start a civil war.” But if you look at the context of the things that have just come before, he’s also sincere. I would submit that, when the rest of us look at very powerful people — particularly those who have control over how we live our lives or do our work in some way — our tendency is to oversimplify them. I think being really marinated in Shakespeare will cause you to say, “There’s probably somebody complicated here.”

Jordan Schneider: Speaking of riling up the crowd, perhaps the most famous riling-up-the-crowd speech in US history of the past 50 years was Donald Trump’s speech on January 6. In rewatching this, I see a few fascinating things. First, Phil had 90 seconds, Trump had 75 minutes, so there’s a kind of different rhythm.

The bits where he is almost masterful in seeding the crowd and raising the energy level, it’s really remarkable. Eliot, any thoughts or reflections on that?

Eliot Cohen: On the one hand, I push back at people who make facile comparisons between Trump and Richard III or Macbeth or Julius Caesar. The Shakespearean characters are frankly a lot more interesting and have more admirable sides to them.

For one thing, the three people I mentioned are all formidable soldiers — whereas Donald Trump had a bone spur, supposedly, which got him out of Vietnam, and he doesn’t actually particularly respect military people. But he is masterful in a way, in knowing how to rile up his people. He is calculated about it.

One of the things that he’s very calculated about doing — and this has been true throughout his career — is just staying on this side of the law. So, you’ll not hear him say, “I want you guys to storm Congress and if you possibly can, lynch Nancy Pelosi.” He’s not going to say that; he’s going to say everything but.

That’s what makes demagogues so dangerous. That is what demagogues do. It’s not so much that they say, “I want you all to go out and riot tonight and massacre Jews or overthrow the government.” They do everything but, and keep themselves at a distance.

That said, let no one doubt: Shakespeare’s command of the English language was infinitely superior to Donald Trump’s — and in the play at least — and so is Mark Antony’s.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting, though, to think about command of the English language. In this book you highlight some of the world’s greatest speeches.

There is a tension of the balance between high and low where, on the one hand, yes there’s something that’s very stirring where you’re pulling from the ur-texts of the English language, the St. James Bible or Shakespeare — but you can also do it Trump’s way and still have a ton of effect.

Phil Schneider: Relating to diction, the “Friends, Romans, countrymen” speech is pretty simple in terms of vocabulary. I think what’s striking about it is the Ciceronian syntax and rhetoric that he’s borrowing from.

There are all of these tri-colons that are really rousing, and you have the repetition of the “honorable man.” The more times this adjective is used, the more it foments a question about the integrity of this leader.

Talking about toeing the line, I think Trump engages a lot of times in a praeteritio, or a walking-about, saying, “I’m not going to say something, I’m not going to say this about such-and-such a person because that would be terrible.” But in his walking around, he actually does say it. So I think we’re curious about how these same rhetorical strategies from the Romans and the Greeks can be used, but with more of an earthy, vernacular vocabulary.

Eliot Cohen: I think that’s a great point, Phil, but part of what Shakespeare does — which people forget to do today — is use the music of the English language: meter and all kinds of devices that you can use to make words effective.

It’s a pity now that people have this idea that Shakespeare’s vocabulary is too complicated to understand. That’s not true at all. A lot of it is actually very straightforward, and some of the most effective speakers know how to do that.

I would also say: some of the most effective speakers in Shakespeare, as in real life, are the ones who know how to speak differently to different people. Nobody does a better job of that than the Shakespearean king who most people absolutely adore, and who I think is a complete skunk: Henry V. He can talk one way when he is trying to seduce a French princess — “oh, I’m just a simple soldier.” He knows how to talk to the common soldiers, partly because he spent his youth hanging around brothels, literally. He knows how to talk to the nobles.

At the very beginning of that play, some of the high clergy are trying to get him to go off to war so he won’t steal their lands, and they say, “This guy is something of a chameleon.” He can speak differently to different people; it’s a very high political gift.

One other thing: Winston Churchill was, of course, a great lover of Shakespeare, and had committed large swathes of it to memory. It was apparently hell to perform Hamlet in front of him, because he would be reciting the speech along with you; Richard Burton describes doing this and how unnerving it was. He tried to speed up and slow down and couldn’t shake Churchill off. But if you look at some of Churchill’s most famous speeches — that’s exactly what he does.

Great Speeches, Great Speechmakers

Jordan Schneider: Let’s pause on Shakespeare; we’ll get back to him later, I promise. On the question of different registers: if you think about the twenty-first century and the greatest American speechmakers, Obama comes to mind. You had this list of what has been magic lately, and you got the Churchill in the 1940s, Kennedy’s inaugural — but you left out what was truly incredible, at least for my generation: the Obama speeches.

Eliot Cohen: Okay, here’s my question to you: give me one or two famous lines from Obama’s speeches.

Jordan Schneider: That’s not the way to do it!

Eliot Cohen: Sorry to disagree, but that is the way to do it. With Ronald Reagan, it’s “the boys of Pointe du Hoc.” For Henry the V, it’s “we few, we happy few, we band of brothers.” With somebody who speaks really successfully, there will be lines that will echo in your head. That’s why Kennedy’s inaugural is so powerful. “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country.” That’s a very simple rhetorical form — chiasmus — where you turn it backward, and Kennedy, among others, was brilliant at it.

I very deliberately did not talk about Obama as a particularly effective rhetorician, because I don’t think he was. I think he was fluent, he could be eloquent, but there is no Obama speech. There are some speeches he gave which I think were good speeches for the time, but it’s not like Martin Luther King’s, “I have a dream.”

Jordan Schneider: Okay, I don’t know where you want to set the bar.

Eliot Cohen: High.

Jordan Schneider: And Reagan crosses it for you.

Eliot Cohen: Yes. Reagan was a consequential president in a way that Obama was not.

Future Jordan Schneider: I’m going to use the podcaster’s prerogative to insert something after the fact, because I’ve been thinking a lot about this back and forth after we recorded it. First off, I think that by dint of being America’s first black president, Obama is a consequential president, and — I would argue — much more likely to be remembered a hundred years from now then Kennedy or even Reagan.

In general, I think people have a hard time appreciating the magic of politicians they’re not particularly sympathetic to. That goes both for Trump and Obama in recent years. I would submit that, even though this wasn’t an Obama-written line, the theater and moment of Obama singing “Amazing Grace” is something that I think is going to echo for a long time to come.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s do perhaps the banger of all bangers. Phil, how about a St. Crispian’s Day?

Phil Schneider:

This day is called the feast of Crispian:

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when the day is named,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say ‘To-morrow is Saint Crispian:’

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars.

And say ‘These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.’

Old men forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day: then shall our names.

Familiar in his mouth as household words

Harry the king, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester,

Be in their flowing cups freshly remember’d.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition:

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

Eliot Cohen: What a brilliant speech. It’s so brilliant in so many ways. He’s going to make these guys brothers. He calls himself Harry the King, so you’re going to be able to say, “I fought with Harry the King.” He’s going to encourage you to brag. He’s going to tell you that you’re a real man, and that for the rest of your life, you’re going to be surrounded by all these gentlemen in England who go around holding their manhoods cheap.

Now, what’s really going on? He’s launched an unjust war. They’re outnumbered — usually when it’s done in the movies, it’s raining, it’s miserable. The speech is tremendously inspirational — and it’s also, at a profound level, false. Because if you look at the scenes just before, the first scene of Act Four, he makes it clear what he thinks of these guys. There’s a long soliloquy which I’ll ask you to read, Phil. This is Act Four, Scene One. Henry’s been walking around the camp at night, incognito, and he’s hearing that his soldiers are not quite sure that this is a just war. They know that they’re the ones who are going to be suffering and dying, whereas the nobles will get ransomed, and finally they say, “If it’s an unjust war, it’s the king’s fault, not our fault. That’s his load to bear.” Henry then launches a soliloquy; he’s speaking to the audience, revealing his innermost thoughts, which go as follows.

Phil Schneider:

Upon the king! let us our lives, our souls,

Our debts, our careful wives,

Our children and our sins lay on the king!

We must bear all. O hard condition,

Twin-born with greatness, subject to the breath

Of every fool, whose sense no more can feel

But his own wringing! What infinite heart’s-ease

Must kings neglect, that private men enjoy!

And what have kings, that privates have not too,

Save ceremony, save general ceremony?

Eliot Cohen: This is what he really thinks; remember, in a soliloquy, you reveal what you really think. These guys are fools; he’s the king. It’s really unfair that they blame him for the completely unjust war that he just started, and he says, “What’s the difference between being a king and being anybody else?” Well, ceremony — but on the next day, he’s going to tell Gloucester, “I want glory, that’s what I really want.” Ceremony is just the form, the corner office. Actually what he’s out for is glory; that’s what he really wants. So in my view Henry’s a complete hypocrite, but he is a brilliant manipulator of human beings, which is what some leaders are.

Phil Schneider: In that speech, Henry V’s education in East Cheap — his curious upbringing in London’s pubs and brothels, manifests rhetorically. His experiences in London’s seedy underground enable him to motivate his soldiers in a way that other leaders in Shakespeare fail to.

Eliot Cohen: Let’s start with the fact that he says, “There I was with King Harry,” which is an informal form of address. Nobody would have dared call his father, Henry IV, who was a very formidable king, Harry, and he would never refer to himself in their eyes as “Harry.”

This speaks to a certain kind of intimacy in the relationship that he has with his soldiers. He understands their desire to brag, so he says, “You guys are going to roll up your sleeve and show the scars.” That does two things; that says, “Yeah, actually you may get wounded in this battle, but you’re going to be able to brag and boast.”

There’s a very interesting contrast with a play that we may be able to talk about later, Coriolanus, where the Roman general is just about to get to the very top of the Roman hierarchy, and then he blows it because the mob wants to see his wounds, his scars, and he thinks that’s vile, that’s disgusting, that’s shameful.

Henry V would probably not show his own wounds, but he understands that these guys do want to be able to show their wounds and that that’s very important in motivating them. The other thing that’s invidious, but which he does deliberately: it’s not just how good they’re going to feel, it’s how crummy everybody else is going to feel for not having been there.

Phil Schneider: Yeah, there’s a hierarchy of honor.

Eliot Cohen: He’s also appealing to some of their lower motives. I think all of that is because he spends the first part of Henry IV and a good part of Henry IV Part Two hanging around in the pubs, in the brothels. He’s being educated by Falstaff, who’s this wonderful comic figure, but very much a low-life. What’s brilliant and shocking about it is that for him to become king, he has to drop Falstaff at the beginning of Henry V, which breaks Falstaff’s heart and really kills him. Shortly before, when Falstaff had asked him for a job, he looks at him and says, “I know thee not, old man.”

To get back to the overall theme of the book and what we can take away from it, I think it shows you: often, to be a really effective leader, you can’t be a nice guy. You can’t necessarily be a straightforward guy, and you frequently cannot show your real feelings and emotions. You end up manipulating people. I think Shakespeare’s right in that sense, and I think he’s also right in at least implying that, alas, it is necessary.

Hanging Up Your Hat (or Staff)

Jordan Schneider: Eliot, the fascinating thing to me about this is: if you’re a leader and you’re running a country, you have to think you are better than everyone else in some way — but at the same time, you can’t think that all the time. You can’t make other people feel that. There’s this weird tension between internalizing your superiority and feeling of deserving all this power. But at the same time, if that’s the only way you manifest into the world, then someone’s going to coup you.

Eliot Cohen: My personal view of this is that people wrestle with that often. The problem is that once they’ve been in power for a while, they can’t throw it off. They forget the moments where they understand, “I’m like you,” as Richard II said, “I need to have friends, and to eat and drink.”

That’s why, toward the end of the book, I talk about people who’ve walked away from power. There’s one, King Lear, who does a terrible job of it. He’s going to divide his kingdom, but he still wants to be treated like he’s king. He becomes furious when his daughters no longer really treat him as a king once he’s abdicated.

The most interesting case for me is Prospero, the magician in The Tempest. He had been a duke, he’s deposed by his brother and is marooned on this desert island. He has all kinds of magical powers and at the end of the play, when he’s done everything he wanted to do, he’s got his evil brother at his mercy, he’s got the king at his mercy, they’ve reestablished their relationship, and he’s marrying his daughter off to the king’s son…

Phil Schneider: This is a beautiful speech. I was lucky enough to assistant-direct an off-Off Broadway production of this a couple years ago, and we had a wonderful older actor who just embodied the magnitude of this character. And because Tempest is the penultimate or maybe third-to-last play Shakespeare ever wrote, some people have likened the speech of Prospero putting down his book to Shakespeare putting down his pen.

He’s conjuring all of the spirits on this island that have essentially been his little fairy slaves, that have enabled him to do his magic over the last couple decades.

Ye elves of hills, brooks, standing lakes and groves,

And ye that on the sands with printless foot

Do chase the ebbing Neptune and do fly him

When he comes back; you demi-puppets that

By moonshine do the green sour ringlets make,

Whereof the ewe not bites, and you whose pastime

Is to make midnight mushrooms, that rejoice

To hear the solemn curfew; by whose aid,

Weak masters though ye be, I have bedimm’d

The noontide sun, call’d forth the mutinous winds,

And ‘twixt the green sea and the azured vault

Set roaring war: to the dread rattling thunder

Have I given fire and rifted Jove’s stout oak

With his own bolt; the strong-based promontory

Have I made shake and by the spurs pluck’d up

The pine and cedar: graves at my command

Have waked their sleepers, oped, and let ’em forth

By my so potent art. But this rough magic

I here abjure, and, when I have required

Some heavenly music, which even now I do,

To work mine end upon their senses that

This airy charm is for, I’ll break my staff,

Bury it certain fathoms in the earth,

And deeper than did ever plummet sound

I’ll drown my book.

Eliot Cohen: Beautifully done. Here’s the thing about this: Prospero is going back to be duke again. He’s accomplished everything he’s wanted. He has these spectacular magic powers, which he’s just cataloged, and which Phil just presented to us. So the question has to be asked: okay, after you’ve done all these things, why do you want to break your magic wand and take your book of magic spells and throw it into some deep trench in the ocean? Wouldn’t you want to hang on to all that?

I think there is an answer to that, and I think the answer is that Prospero has come to recognize that the exercise of this rough magic — the original working title of my book was Rough Magic, off the idea that power is a kind of rough magic — was dehumanizing him in some way. It’s very striking: at the very beginning of the play, when he’s explaining how they got to the island to his daughter, who’s he kept very sheltered, he has to take off his magic robe, and she has to help him take it off.

He can’t speak to his daughter the way a father should speak to a daughter while wearing his magic robe, his robes of power. It’s not that he’s cheerful about any of this; he says, “I’m going to go back, and my every third thought will be of the grave. I’m an old man. I’ve begun thinking about death.” But he is a much more attractive human being when he has relinquished power. That’s part of what makes him a compelling figure.

In the book, I talk about leaders who’ve been unsuccessful at leaving power, but also those who have. Of course, the great one from American history is George Washington, who did it twice, first as commander of the Continental Army, after Independence has been won. He makes a very big production — by the way, he loved Shakespeare, he loved theater — of returning his commission to the Continental Congress where he stood and they sat, making very clear who’s in charge, and he hands over the paper commission.

Then of course, he later steps down as president. The most impressed spectator to all this, from a distance, was King George III, who twice said, “If he does that, he’ll be the most remarkable man of the age.” I think Washington understood that, and like Prospero, neither retirement was particularly happy, for a whole bunch of reasons, including his health, but going well beyond that. But it is part of what made him a truly great man, as well as a great leader.

Jordan Schneider: So we’ve had the beautiful exits. We’ve also had some not particularly beautiful exits, two of whom are currently running for president in their late seventies and eighties. It’s exceedingly rare for people to know when to hang up their hat.

Eliot, let’s start with Shakespeare and then we’ll talk about Biden and Trump.

Eliot Cohen: I think the best example of this is toward the end of Henry IV Part Two, when the father of Henry V, the guy who gives the St. Crispian’s Day speech, is dying. Prince Hal, as he then is, comes in to pay his respects and sees the crown. He thinks his dad has croaked and he puts the crown on his own head, and his father wakes up and there’s a furious scene. They sort of reconcile at the end — but the thing that’s so striking about Henry IV’s exit, and particularly these rather harsh words that he addresses to Prince Hal, is that it’s clear that he doesn’t think anybody else can do the job that he’s done.

If you think about it, that’s Trump’s “I alone can do it” — but I think it’s also, alas, where President Biden is: “I’m the only guy who can really defeat Trump and run the country properly.” Which is nonsense, but I think it’s understandable for somebody who’s been in the Senate for half a century or something like that. It is a good example of how power messes with your sense of reality.

Phil Schneider: The Prince goes, “I never thought to hear you speak again.”

And his father replies:

Thy wish was father, Harry, to that thought:

I stay too long by thee, I weary thee.

Dost thou so hunger for mine empty chair

That thou wilt needs invest thee with my honours

Before thy hour be ripe? O foolish youth!

Thou seek’st the greatness that will o’erwhelm thee.

Stay but a little; for my cloud of dignity

Is held from falling with so weak a wind

That it will quickly drop: my day is dim.

Thou hast stolen that which after some few hours

Were thine without offence; and at my death

Thou hast seal’d up my expectation:

Thy life did manifest thou lovedst me not,

And thou wilt have me die assured of it.

Thou hidest a thousand daggers in thy thoughts,

Which thou hast whetted on thy stony heart,

To stab at half an hour of my life.

Eliot Cohen: What’s so striking about that is that line: “O foolish youth! Thou seek’st the greatness that will o’erwhelm thee.” You’re not up to it, kid! That’s what he’s really saying. It’s partly because Hal is a very different guy than Henry IV in some ways. In other ways, he’s actually very similar — they’re both manipulative, duplicitous, cunning, ruthless, characters.

Henry IV can’t let go, and he can’t believe that his successor will be able to do the job. By the way, that’s extremely common in the world of business and just about everywhere else; people are just convinced, “so-and-so is going to be the next CEO, but I bet you they can’t handle it.”

Jordan Schneider: I love the Churchill quote you had; he’s 80 years old, and he says to and Antony Eden, the guy’s anointed successor who he’s been training for 15 years, “I don’t think he’s got it. He doesn’t have the juice.” Mao ran through seven people; Reagan ran through seven people.

To get to this point, so many things have gone so right for you, and then you live a life for five, ten years where everyone around you is telling you how brilliant you are, and you have a whole institution whose job it is to make you seem infallible. Then to acknowledge, “I’m actually replaceable and someone else can step in and things won’t fall off the rails” is a tricky psychological thing to get around when you’re at the end of your life.

Eliot Cohen: There’s one another part to it, which is that you’ve also suffered, because powerful people suffer on the way up. Their sense of responsibility, their fears, the mistakes that they know they made that other people don’t know they made … I think any leader is carrying a lot of scars around with them, and that contributes to that feeling of “you don’t know what I went through, and I doubt that you could get through it the way I did.” I agree with everything you said, but I think that’s another element.

Phil Schneider: I was just going to paraphrase the author’s words: there’s an inability to accurately assess his own succession that arises from a failure to fully understand himself.

I wonder what the St. Crispian’s Day speech would sound like from the mouth of this leader. He’s wary of someone who perhaps possesses a strength that he himself doesn’t.

Eliot Cohen: I think that’s right. Succession often goes badly. Most of the examples I give in the book are historical or current political ones, but I do have some business examples. I talk about Jack Welch, the famous head of GE, who really built it and developed, among other things, a very elaborate program for selecting people and grooming people for higher positions. His personally selected, carefully vetted successor was Jeffrey Immelt, who presided over the breakup of GE, and effectively, its collapse.

I contrast this a bit with Steve Jobs at Apple, who actually very successfully picked a successor, one who was very different from him, from the button-down culture of IBM, who had a different skillset. The reason why, I suggest, is because Steve Jobs had suffered a lot. He had been fired twice from big jobs in big, humiliating ways, and he was a cancer survivor, although he eventually died of it. This had induced a kind of humility in him, which I think is very rare in high level leaders. I suspect that the suffering that gave him that humility is actually what also allowed him to pick a successor who grew Apple far more than he did.

Jordan Schneider: Thinking about the idea of running all these quantitative tests to find our next person — but at the end of the day, if the top person in charge is the one choosing the successor, there’s going to be so much human attachment. “Who reminds me of my son or daughter?” That kind of thing is going to end up bleeding into it, and that’s really where you get thrown off.

It’s not this idealized version of a Chinese meritocracy where first you run your city well, then you run your state well, and you get promoted or not. It comes down to these personal relationships, and just because you can win over your boss and play court politics well, doesn’t necessarily mean that if you’re in the seat, you’re going to be able to drive in the way that the country needs you to.

Eliot Cohen: Or it may simply be that the tasks which your successor are going to have are very different than the tasks that you had. Again, I think one of the things you can learn from Shakespeare — and from elsewhere, too — is that leaders are not fungible. It’s not a universal competence where the same person is good for every situation.

I’m a military historian, essentially. There are some generals who are great at fighting defensive wars; there are some who are great at fighting offensive wars. There are some who are great at conventional war; there are some who are great at irregular war. You shouldn’t assume that they’re all equally good at each of them.

Jordan Schneider: Let me speed-run through some other observations I had about your book. Henry V, when he meets Kate, the French queen, she goes, “Oh, I don’t want to kiss you, I don’t kiss people.” Henry goes, “Oh, Kate, nice customs curtsy to great things,” which immediately conjured up Trump’s 2005, “I just kiss women. They let you do it. You can do anything when you’re a star.”

The violence arc that you portray in Macbeth of a series of murders all working, all of a sudden becoming a pattern — I love the little parallel you drew there from mass murderers to Thane of Cawdor…

But what do you want to end on?

Eliot Cohen: Well, I love Coriolanus.

Jordan Schneider: All right, we can end there.

Eliot Cohen: I like dark, and Phil, if you could give us the speech where Coriolanus loses it. Coriolanus is the story of this great Roman general who wants to be Consul. He’s been very successful. He almost gets there, and then the crowd says, “We want to see your scars,” and he loses it. Phil, that’s the passage I’d like you to do, and another passage of a different kind that I’ll ask you to do later on. It’s a wonderful moment where he’s furious at being asked to show his wounds.

Phil Schneider:

Better it is to die, better to starve,

Than crave the hire which first we do deserve.

Eliot Cohen: He really wants to be just appointed to this job. He doesn’t want to have to campaign for it. What really drives him around the bend is when they ask him to show them his wounds.

I taught this once in a class. My students were pretty much all graduate students. The class included about half a dozen veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan and Libya. I said to them, “You don’t have to answer the question, but let me ask you: has anybody ever asked to see your wounds?” That part of the conversation went on for an hour, because they all had been asked that. Many had the same reaction that Coriolanus had: “How dare you, I did this out of honor, I did this out of service, and you want to look into my soul and feel sorry for me? You can’t understand what it is that I went through.”

It really hit me; it’s one of the ways in which Shakespeare speaks to us and to some essentials of the human condition. In some ways those haven’t changed.

Now, where this ends up is a pretty dark place; maybe you could read that speech, Phil.

You common cry of curs! whose breath I hate

As reek o' the rotten fens, whose loves I prize

As the dead carcasses of unburied men

That do corrupt my air, I banish you;

And here remain with your uncertainty!

Let every feeble rumour shake your hearts!

Your enemies, with nodding of their plumes,

Fan you into despair! Have the power still

To banish your defenders; till at length

Your ignorance, which finds not till it feels,

Making not reservation of yourselves,

Still your own foes, deliver you as most

Abated captives to some nation

That won you without blows! Despising,

For you, the city, thus I turn my back:

There is a world elsewhere.

Eliot Cohen: It’s a wonderful depiction of a leader who’s been rejected; that happens too. The fury of it leads Coriolanus to commit treason and nearly destroy Rome.

We’ve doing a lot of high drama here — murderers, battles, stuff like that. Shakespeare is also capable of describing the ways in which the more human kinds of leaders, not always the most successful ones, I might add, can have a very human side.

So maybe let’s go back to where we began: to Julius Caesar. Phil, I’m going to ask you to read the dialogue between Brutus and Cassius from page 86 of the book. In Julius Caesar, there’s Brutus, who’s a bit of a prig and Cassius, who’s a manipulator, who was the mastermind behind the coup that killed Julius Caesar. They’re about to fight the big battle against Mark Antony and Octavius and Lepidus, which as it turns out, will end in their deaths. And the two of them have had a major falling out. Then they realize that there’s been something of a misunderstanding. They reconnect as Cassius realizes, “oh my God, Brutus’ wife, to whom Brutus had been devoted, just died.” They reestablish a human connection. Phil, maybe you could finish us off with that.

Phil Schneider [as Brutus]:

And whether we shall meet again I know not.

Therefore our everlasting farewell take:

For ever, and for ever, farewell, Cassius!

If we do meet again, why, we shall smile;

If not, why, then this parting was well made.

Jordan Schneider [as Cassius]:

For ever and for ever farewell, Brutus!

If we do meet again, we'll smile indeed;

If not, ‘tis true this parting was well made.

Eliot Cohen: I always find that one of the most moving parts of that play. These are two flawed leaders. Neither is entirely successful, but there’s true friendship in those lines. The way Shakespeare shows you there’s true friendship is by having Cassius mirror Brutus’s own sentiments back to him, that this may be a forever and forever farewell, and maybe we’ll survive and if so, we’ll have a good laugh about it. And if we don’t, the parting was well made. I think Shakespeare reminds us that you can strive and you can try and you can lead and you may fail, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that you simply have to lose your humanity.

Jordan Schneider: Last question for you, Eliot. You recommended a handful of other pieces of fiction that you think help elucidate some of the themes that you raise here. Why don’t you give us three novels to take us out on?

Eliot Cohen: Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men, which is basically about Huey Long, the governor of Louisiana, a demagogue, is a fantastic political novel.

Another political novel would be Edwin O’Connor’s The Last Hurrah, which is a fictionalized account of James Curley, who was a very famous, rather corrupt, Boston politician. It’s a very intimate, and somewhat sympathetic, look at politics in an ethnically divided city, and at what motivates the mayor, who wants another go-around.

Then there’s the big one: Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Tolstoy has a darker view of leaders, particularly Napoleon. There’s so much in War and Peace, but one part of it is considering how much of the time Napoleon is fooling himself about his ability to control events. It’s not that Tolstoy depicts him as a monster; he doesn’t. He depicts him as a bit of a fool, and that’s a different kind of take. Historically accurate? I’m not so sure. As a novel? Fabulous.

Jordan Schneider: We’re going to close with Orson Welles talking to Dick Cavett in 1970 about Marshall and Churchill.

My wife made a great point - for the Reagan and Kennedy eras, for example, the information pipeline was print and nightly news. It was hard to avoid the attention and focus mainstream media put on these speeches and administrations. By comparison, today, not only is there an info funnel, it can be curated according to one's bias. Not to mention the exhaustive coverage on political figures such that there is hardly a recognizable news cycle - I can all but guarantee anyone who follows politics knows more about Obama than ever did about Reagan.

For my two cents, I think Reagan vs Obama as consequential presidents is a silly debate. Reagan initiated and presided over the beginnings of the culture wars that have debilitated even Congress, insurmountable income inequality, and the acceleration of the Christian conservative power grab. Reagan may be consequential, but only in the notorious sense to so many of my Gen X.

The speech from Richard 2 is well before his disposition