Hi folks, in early September I’m likely heading out to Taipei (and hopefully Tokyo as well). If you’re in town it would be great to meet up. To connect just respond to this email.

The following is the first article from ChinaTalk’s newest editor, Wu Fan, a recent NUS sociology graduate who specialized in East Asian media culture.

Earlier this year, Xi Jinping conducted his third visit to Xiong’an New Area 雄安新区, a smart city in construction he referred to as the “city of the future.” It will aid the coordinated development of pre-existing city clusters, including the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region 京津冀, the Yangtze Economic Belt 长江经济带, and the Yangtze River Delta 长三角. Simultaneously, the project will help relieve Beijing of nonessential functions to its role as a capital — in particular, maintaining its position as China’s political, cultural, international communication, and scientific innovation center. Xi envisions this “millennium project” to be free of urban maladies 城市病; in fact, the residential aspect of this “COVID-proof” smart city was inspired by the challenges of living “a full life in times of confinement.”

Similarly, Tencent in 2020 revealed grand plans to build a smart city, touted as a model for post-coronavirus China. Coined “Net City,” the 21.5-million-square-foot project in Shenzhen will house Tencent’s new headquarters, residences for its employees, as well as public amenities.

Smart cities — which combine the latest info-communications technology (ICT) with urban management — are now framed as the comprehensive solution to China’s many big-city problems.

Yet for all their potential, China’s smart-city initiatives, as said best by Xu Chengwei of Singapore Management University, “are not driven primarily by market demand, but by political and technological ambition.” This approach risks:

Disregarding the surveillance and security implications of smart-city technologies, and

Overshadowing other important benefits of smart cities — namely, sustainability and human-centric social systems.

What is a Smart City, anyway?

There is no single definition, but one of the most widely accepted is the following:

A smart sustainable city is an innovative city that uses information and communication technologies (ICTs) and other means to improve quality of life, efficiency of urban operation and services, and competitiveness, while ensuring that it meets the needs of present and future generations with respect to economic, social and environmental aspects.

A smart city’s key characteristics are

connectivity — devices and systems implemented are connected to each other or some central “brain”;

data — connected devices are exchanging and generating information; and

government involvement — a smart city without the public sector is simply the Internet of Things.

China began converting its smart-city dream to reality since it established its commitment to smart cities in the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011-2015). Since then, ICT companies have been riding the hype train spearheaded by the government: the market size of the Chinese smart-city industry has skyrocketed over twenty-five-fold in less than a decade.

The key players in China’s rapid smart-city-fication are all internationally renowned tech giants. Apart from Tencent, there’s Alibaba’s City Brain system, which took root in Hangzhou and has now been implemented in over twenty cities. ZTE Corporation, a major international ICT provider, runs multiple transportation networks based in Guangzhou, branching off their 5G Smart HSR Vehicle-to-Ground Communication system. Hikvision’s surveillance security system, Huawei’s 5G networks, and AI-driven smart transport by Baidu and Didi round off the biggest names in the industry.

In China, the problems that smart cities seek to address include congestion, pollution, and also public-health and resource-allocation issues brought to light by the COVID-19 pandemic. The digitization of urban management systems made it possible to monitor, control, and contain the spread of the infection — and the government must have caught on: the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) highlights innovation at the center of the modernization agenda, a large part of which involves using state-of-the-art technology for “prevention and control” 防控 of infectious diseases.

Adhere to the guidelines of government-people alignment and mass defense mass government, in order to raise well-roundedness, rule of law, specialization, and digitization of social security. … Adhere to the combination of prevention and control, overall prevention-and-control, strengthen the investigation and rectification of key areas of social security, and improve the coordination of social security joint efforts. Promote the construction of public security big data intelligent platforms. Improve the checks-and-balances for law enforcement and judicial systems, and improve the mechanism for protecting the rights and interests of law enforcement and judicial personnel. Build a national security prevention-and-control system. Deepen practical cooperation in international law enforcement and security.

In line with the concept of prevention and control are efforts to reduce pollution, monitor natural reserves, and curb social unrest. ICT will be used for “mass defense and mass governance” 群防群治, a social security system that China has been implementing since the 1950s.

China also launched a national plan — the China Standards 2035 — to set the standards for the next generation of technology. Blockchain, cloud computing, 5G, AI, and geographic information systems (GIS) will be pushed to take center stage both on local soil and internationally.

The fine balance between hyper-surveillance and (in)security

Observers in China and abroad have duly noted that China’s smart cities are really surveillance cities where the close monitoring and management of large populations lay the foundation for national security. Indeed, there’s almost one CCTV for every two people in China — and these cameras not only use facial recognition but also emotion-detection technology that, for instance, can predict problematic behavior in public spaces. Via sensors which collect data 24/7, surveillance has extended its reach from urban infrastructure to everyday home appliances and personal electronic devices. Citizens gain some operational efficiency via optimized systems — particularly in transport — but at a great cost to their liberty.

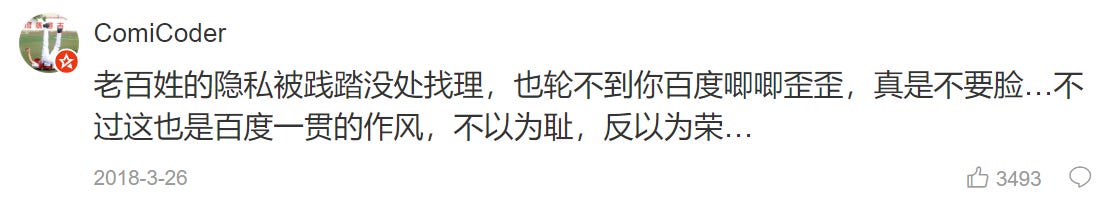

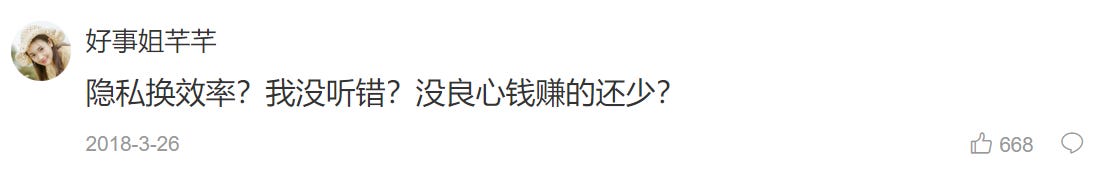

Tech giants are taking the lead to allay public outcries against this pervasive hyper-surveillance — but often to greater backlash. For example, at a 2018 panel discussion in Beijing, Robin Li 李彦宏 — the CEO of China’s biggest search engine, Baidu — claimed that “Chinese people are more open or less sensitive about the privacy issue,” since they would be more willing to “trade privacy for convenience, for safety, for efficiency.” Chinese netizens quickly and harshly criticized his claims on Weibo:

Baidu is in no place to yammer about people’s privacy getting trampled on with nowhere to seek recourse. You’re really shameless … But then again, this is just how Baidu does things; they’re not ashamed of it — in fact, they’re proud of it!

Exchanging privacy for efficiency? Did I hear it right? Earning so much money without a moral conscience?

Indeed, the power imbalance between the netizenry and control of media opinion has not stopped many from airing their dissent about how these top-down systems are “ruining their lives.” On popular Chinese blogsite Wangyi 网易, office workers shared that behavioral sensors in employee surveillance systems which track their every move on company devices have led to instant expulsions without any negotiation. This system of behavioral sensors quantifies employees’ usage of company devices to perform “resignation inclination analysis” 离职倾向分析, in effect reducing each individual into a mere statistic; this analysis is used by more than 100,000 companies in China. It’s no wonder that sentiments like the following are spreading like wildfire:

Getting fired on the first work day of the year — just my luck! Before the Chinese New Year, we were informed that we’re not receiving our year-end bonuses because the company has not been performing well, so I started to apply for new jobs right away. I was planning to hop over to a new company the moment I got a job, but who would have thought that I’d be called in by my boss the moment we returned back to the office? And I received a whole reprimanding: “Don’t think I don’t know what you’re doing while at work — I know exactly when you want to leave the company!” While I was still stumped, my friend sent me this screenshot — it’s truly a wakeup call. Look here, everyone! It’s all thanks to this Sangfor Technologies 深信服 and all their [redacted swear word] business!

On the political end, COVID-tracking apps were used by authorities to curb protests amid messy public health management policies which, ironically, the apps were originally intended to serve. In fact, in 2022, protesters in Zhengzhou fighting to recover their frozen savings from banks found that their clearance status on the app turned from green to red, indicating that they were no longer permitted to move freely. Systems like these conveniently create exclusionary criteria on citizens’ mobility — geographically and socially.

With hyper-connected systems stored on the cloud, the promise of security frequently comes under scrutiny in the event of security lapses.

In 2019, security researcher John Wethington found a Chinese smart-city database hosted by Alibaba that could be accessed from a web browser without a password. The database held hundreds of facial recognition scans — gigabytes of data — that made several references to Alibaba’s City Brain.

The 2022 Shanghai data breach let loose twenty-three terabytes of personal identifying information (PII), ranging from passport numbers to food-delivery records. The data were offered for sale for over $215,000. The government has sought to erase nearly all discussion on the matter.

Chinese “digital authoritarianism” and the “world digital brain”

It is no wonder, then, that anxieties around China’s “digital authoritarianism” are on the rise. Indeed, in a sharing by Samm Sacks, a senior fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, the cybersecurity maturity of many Chinese companies prior to the 2017 Cybersecurity Law was so low that for some companies “the baoan, the security guard, was their cybersecurity point person.” In view of the data breaches since, we can only ponder how effective these regulations have been.

The muddy parameters that define smart cities in policy papers create problems of their own. Local agency is inevitably curtailed, because it is difficult for importing countries to scrutinize the complexities of city brains which extensively deploy AI. The lack of transparency also means that municipalities are not in full control of where their city’s data is stored and who has access to it, especially when it is supplied by a foreign country.

Huawei’s projects on foreign soil have been met with mixed responses: collaborations have been halted in Germany and France, which take a harsher stance regarding Chinese technologies entering their critical infrastructure. Meanwhile, Malaysia and Indonesia have readily taken up projects across many of their cities. The reception of China’s smart-city technologies roughly draws parallels to geopolitical alignments with or against the US — which isn’t surprising in light of the US-China “Tech Cold War.”

To that end, the distinctions between “safe” and “smart” cities are often blurred. The frontrunners in China’s smart-city development — Huawei, ZTE, Hikvision, Dahua Technology, and Alibaba — have been exporting “safe city” and “smart city” packages to cities around the world, especially China’s strategic partners. State media claim that “the Chinese solution” — China’s high-tech measures to manage the COVID-19 pandemic — reflects the systemic advantages of domestic smart-city technologies.

Liu Feng, deputy director and secretary-general of the Urban Brain Special Committee of the Chinese Society of Command and Control, lays out a geopolitical vision for Huawei’s City Brain:

[It will] gradually expand from the city brain, to the provincial brain, national brain, and finally the world digital brain [世界数字大脑] or a world digital nervous system. The construction of the world’s digital brain will be the third important opportunity to establish the world’s technological ecological standards and systems after TCP/IP and the World Wide Web.

Lessons from smart-city successes

Although the invasive nature of surveillance and digital governance in China is often faced with rampant skepticism by observers, China’s smart-city projects are not without their merits.

For instance, Hangzhou’s ranking as the fifth-most-congested city in China fell to fifty-seventh after the launch of City Brain. The AI algorithm that manages more than 1,000 road signals around Hangzhou has improved emergency-response times to (potential and real-time) traffic accidents by up to 49%. In fact, surveillance has even helped to identify images of traffic violators with 95% accuracy in Shenzhen via computer vision technologies incorporated into the roadway surveillance network.

The wider goal of inclusive urbanization has also been gradually achieved in some cities via increased accessibility and efficiency of government, healthcare, and social services.

In Shanghai, the municipal government offers residents more than 100 streamlined government services through a Citizen Cloud platform mobile app. Citizens can easily retrieve their driver-license details and health records, as well as reach out to local services.

Similarly, Guangzhou launched a regional health-information platform that not only stores residents’ electronic health electronic health records, but also is linked to local hospitals and clinics. Through an integrated smart medical app, healthcare institutions can offer patient services, including appointment booking, fee payments, and home delivery of prescription drugs.

A uniquely Chinese advantage is its planned “city cluster” 城市群 approach, which aims to boost economic growth and ecological sustainability. President Xi spearheaded this regional approach in 2014 by first appointing Beijing as the leader of the development of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region 京津冀. By 2035, five major city clusters are expected to be established in China — many of which have already taken shape and are becoming powerhouses of China’s GDP as well as urban expansion. The geographic distribution of Chinese smart cities tends to align with these regional economic development patterns, which include city clusters, satellite towns, and the rapid construction of the nationwide grid of high-speed railways.

To be sure, many of these successes come from more affluent cities which are typically more well-equipped to leverage ICT. Even so, researchers also note that “second- and lower-tier cities enjoy more freedom to innovate with fewer bureaucratic restrictions and may therefore play a larger role in prototyping new technologies and service models.”

The future of smart cities and digital urbanization in China

It is difficult to assess China’s actual progress in smart-city development, as most candid assessments are likely controlled documents meant only for internal government circulation. Many research centers inevitably rely on network surveys, databases, and unspecified data analysis methods to rate and rank smart-city projects. In fact, “instead of publishing detailed official assessments, official media outlets trumpet quasi-official studies as indicators of smart city development.”

For now, only time will tell if China’s smart cities stay true to the nation’s urban vision: to directly benefit residents, rather than simply make administrations efficient — tracing back to Premier Li Keqiang’s government work report delivery in 2014 that emphasized “human-centric new-style urbanization.” Technology is the key to building a smart city, but it is not enough to make a city smart, and neither is it the end goal.

Next up, how Alibaba’s smart-city platform suffers from uniquely Chinese flaws

By Luke Cavanaugh, who produces interweave.gov, a newsletter covering digital government developments in Europe and Asia.

In early 2018, Alibaba Cloud executive Min Wanli addressed a packed conference center in Kuala Lumpur. “Every moment [human beings] are sensing different signals either through our eyes, our hearing, our speech, our text messages,” he began. “The body digests and extracts the most important information and then decides what action you want to take.” But why, he asked, could a city not do this, too?

Min’s question was far from hypothetical. He was discussing the technical detail of a collaboration between the Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC) and Alibaba on the introduction of the City Brain to Malaysia. It was a project that Min had been working on in Hangzhou, where Alibaba is headquartered.

The City Brain began in 2016 as an intelligent transport system. Its artificial intelligence focused on processing data in real time based on current traffic status and speed information, using it to adjust bus frequencies and control traffic lights. Hangzhou, once one of the most congested cities in China, saw its average congestion time reduced by more than 15% during the platform’s first year of operation.

Its scope today is far broader. From the Industrial Brain to the Medical Brain, the Environmental Brain to the Financial Brain, Alibaba is deploying artificial intelligence and neural networks across Chinese society.

But as a standout example among China’s Smart Cities, the City Brain is the product of a unique political system. Government backing has allowed the City Brain unparalleled access to data and the ability to scale. With total Chinese investments in Smart Cities surpassing 2.4 trillion yuan in 2020, and Xi Jinping himself reiterating the importance of China’s digital government strategy this year, the stakes for success are high.

And it’s not just the ongoing tension between Alibaba and the government that threatens to derail its vision.

Stick around for 2000 more words of reporting on challenges to domestic development and the international prospects of China’s Smart Cities vision.