Why did the Soviet Union collapse? Which lessons from Cold War history are relevant for China’s future?

To discuss the successes, failures, and strategies of Soviet leaders, ChinaTalk interviewed Yakov Feygin. Feygin is the author of Building a Ruin: The Cold War Politics of Soviet Economic Reform, which examines how various Soviet leaders, institutions, and economists attempted to boost Soviet growth and national power.

Co-hosting today is Jon Sine of the Cogitations substack.

Listen now on Spotify or Apple Podcasts.

We discuss:

The strengths and limitations of the Stalinist economic model,

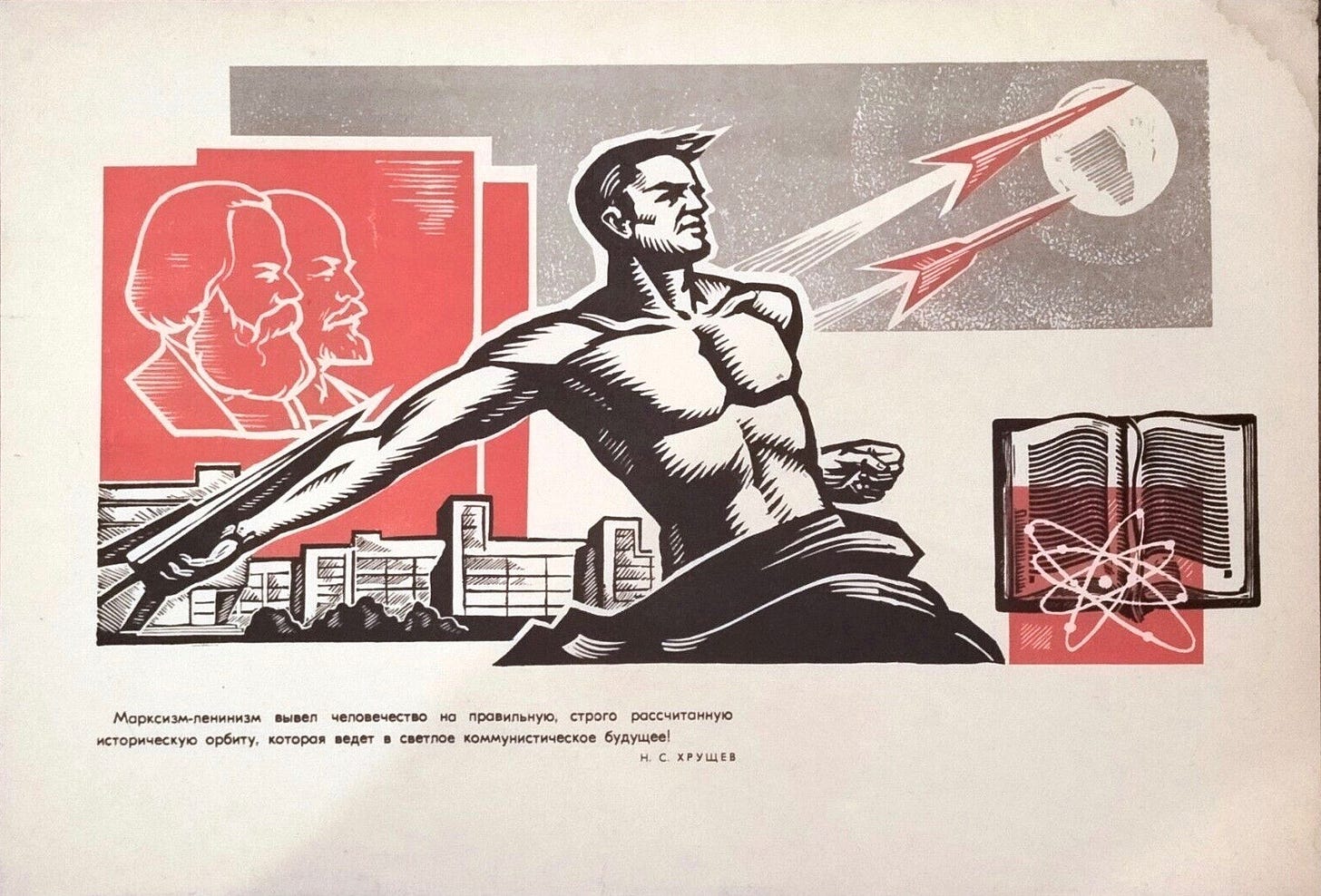

Khrushchev’s shift to “peaceful competition” with capitalism,

Alternative policy paths that could have saved the Soviet Union,

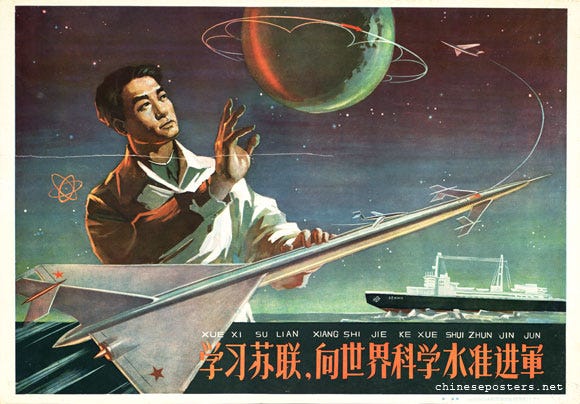

How technological optimism shaped Soviet reform efforts, inspiring the CCP in the process,

Parallels between the institutions of the Soviet Union and those of contemporary China,

The battle between political scientists and historians when analyzing the political economy of authoritarian states.

Post-Stalin Policy Struggles

Jonathon Sine: This is an excellent book, Yakov. Let’s dive right in. What’s the main thesis of your book, and how does it relate to the world today?

Yakov Feygin: The main thesis explores Soviet domestic politics and the evolving concept of a socialist project in the post-Stalin era, which is intrinsically tied to the definition of a socialist economy. To understand Soviet politics, one must consider the Soviet Union’s larger global project as an anti-capitalist state. After Stalin’s death, various factions and new ideas emerged, embedding themselves in specific institutions and attempting to reinvent the system.

This reinvention was a rolling political process that continually redefined socialism while ultimately destabilizing the institutional underpinnings that made it coherent. The Stalinist planned economy, despite its intellectual veneers, was built on specific assumptions about how the world, capitalism, and international relations were supposed to work. In a dark sense, it functioned for its intended purpose. However, as society became more complex and the capitalist system evolved — no longer defined by imperialism as Lenin saw it, but by a hegemonic system with American superpower— the old system ceased to be effective.

The question then became, what comes next? This story has resonances with the Russian and post-Soviet political systems to this day and may offer lessons for other comparative systems.

Jordan Schneider: That’s an interesting closer, Yakov. While reading this book, I kept drawing parallels with Xi’s China, Deng’s China, and Mao’s China. Let’s start with Stalin — what was the Stalinist model, and why did it make sense for the USSR at the time?

Yakov Feygin: The Stalinist model shares similarities with other modernization efforts. The core of this model is a macroeconomic principle — rapid modernization requires substantial fixed capital installation, necessitating a high rate of investment. The identity S=I means the savings rate must increase significantly.

Most developing countries have raised their savings rates considerably at the start of their industrialization. The short to medium-term gains from this approach can offset the reduced household consumption, as productivity gains push the economy closer to its production possibility frontier. Many emerging or developing countries undergo this process, which partly explains why the Soviet Union was popular as a model in the 1960s and 1970s.

However, not all countries commit genocide against their peasant classes — that’s a particular feature of Stalinism. To understand why this happened, we must consider the Stalinist worldview.

The 1917 revolution — enabled by fissures in the imperial system — remained within Russia’s borders.

Consequently, the Soviet Union had to modernize rapidly outside the rules of standard profitability to avoid foreign capital influence. This approach — intimately tied to geopolitics in Stalin’s mind — aimed to prepare the country as a base for a longer-term revolutionary process.

This system was designed to achieve high industrial modernity and rapid, large-scale outputs in critical sectors. These weren’t directly military tools but built a framework for independence from capitalism and power to operate in the imperial world, directed towards a larger long-term goal.

Jonathon Sine: It’s interesting how people often forget the high growth rates under Stalin. Even later, economists predicted the Soviet Union would overtake America within a decade or two. The party served as a mobilizational element underpinning this forced industrialization drive.

Could you describe the key institutions that Stalin put in place for a planned economy, especially since China today doesn’t have a planned economy in the same sense as the Soviet Union?

Yakov Feygin: That’s an excellent question. The Stalinist planned economy was chaotic, as detailed in works by scholars like Paul Gregory. The plans weren’t really plans — they were more like throwing ideas at a dartboard to see what stuck. There was a veneer of planning in the institutions, but they didn’t accomplish much.

The first five-year plan relied entirely on inertia and trial and error, often enforced through extreme violence and repression, especially of the peasantry.

Starting from a low base with a large population surplus allowed this approach to work initially. However, by the third five-year plan, there was a growing realization that some logic or reason was necessary, and the very high investment rates needed to be moderated. Steps were taken to professionalize the planning bodies, though this process was interrupted by the onset of World War II in 1939.

Through the mid to late 1930s, there was an increasing understanding that simply throwing resources at problems wasn’t sustainable — the rate of investment needed some rhyme or reason, or returns would be inefficient. Even Stalin began to discuss the negative consequences of “storming” practices. However, a deep disjuncture remained between what some would call Stalinist romanticism or revolutionary romanticism and the need for more planned expertise. This tension was never fully resolved.

Khrushchev’s Hurdle and Socialism in One Country

Jonathon Sine: There’s an interesting quote from Stalin where he says, “The planned economy is not our wish; [but] it is unavoidable or else everything will collapse.”

He goes on to say that the main task of planning is to ensure the independence of the socialist economy from capitalist encirclement. It sounds like he didn’t necessarily intend to have the sort of planned economy that ultimately developed. Could you discuss this and then lead us into how Khrushchev upended that model?

Yakov Feygin: That quote indeed speaks volumes. The practices of Soviet planning were largely improvised and closely tied to Stalin’s political priorities and the attempt to understand what “socialism in one country” meant. There’s a misunderstanding that this concept simply equates to Great Russian chauvinism or Soviet capital-I Imperialism, but it was still very much a revolutionary project. The question was how to have a revolution when the global environment wasn’t as friendly as it had been in 1917.

As Stalin consolidated power and built his framework, many choices were stark. With the assumptions about battling world capitalism and foreign markets collapsing during the Great Depression, improvisation became necessary. For instance, there were initial plans for the Soviet Union to be a major grain exporter, starving its peasantry to accumulate capital. However, it ended up relying mostly on gold exports because the grain markets collapsed.

The quote you mentioned comes from a very interesting meeting where Stalin was addressing economists who were arguing about how to write a textbook for Soviet colleges. The main point of contention was the role of planning in the Soviet economy — whether it had abolished market relations entirely, or if the Marxian law of value still applied in some areas. Stalin’s response was pragmatic, acknowledging that the planned system was improvised rather than designed from the top down. He noted that while state industry was no longer affected by the law of value, there were still gaps, particularly in agricultural markets that weren’t fully socialized.

Moving on to Khrushchev, his era needs to be understood in its political context. Khrushchev — and Stalin’s other successors — were dealing with several challenges including,

A disorienting domestic situation with bottled-up social pressure that had been accumulating since the late Stalin period.

Expectations for change, as the population felt that it had sacrificed a lot, and already proven its loyalty through war. People felt that it was time to start seeing results from that hardship.

The Cold War started playing out differently than Stalin had expected, with the consolidation of American hegemony and the creation of an open trade bloc. France and Britain stayed on-side much more than Stalin expected.

These factors combined to require a new narrative for Soviet legitimacy.

The debate between Khrushchev and Georgy Malenkov in 1955 is a crucial moment in Soviet history.

Malenkov was Stalin’s official successor — he was the Premier of the USSR for a year. He appeared to be a typical Stalinist, but crucially, his wife was one of the USSR’s leading economist-engineers specializing in electrification infrastructure. Such projects have high initial capital requirements and low subsequent costs — a dynamic that forced Malenkov to think about the problem of investment allocation between consumer and industrial goods.

After Stalin’s death, Malenkov advocated for reducing the rate of investment in heavy industry. He gave speeches suggesting compromises with the United States and Europe.

These positions made him deeply unpopular — Malenkov’s argument about the contradiction between consumption and investment implies that the Soviet Union would inevitably be threatened militarily by the capitalist world. That culminates in Khrushchev’s triumph.

Khrushchev emerged as a true believer, who thought the Soviet planned system could simultaneously increase production and consumption without facing trade-offs. He believed that the system’s problems stemmed from the population’s increasing alienation and the disconnect between the grassroots and the party leadership.

Under Khrushchev’s leadership, the USSR doubled down on fixed capital investment and made management by cadres more efficient, resulting in significant growth.

Simultaneously, Khrushchev dismantled some of the central structures that had previously managed the system. This combination of factors creates an almost perfect storm in Soviet economic policy.

Jonathon Sine: Let’s focus on that point where Stalin dies and Khrushchev doubles down on investment. This gets to the crux of the argument in your book, which is the issue of distribution. The party-state continuously put resources towards heavy industry under Stalin. Production ministries funneled more and more money towards machinery and goods that could be used for war. Khrushchev effectively doubled down on this approach, though not so much in a war mobilization sense.

What is this distributional issue, and why is it the fundamental problem of the Soviet economy?

Yakov Feygin: The distributional issue in the Soviet economy is rooted in the ideas of the economist Michał Kalecki, who explored the sources of profits under capitalism even before Keynes.

Kalecki argued that profits come from final consumption, which in turn comes from capitalist investment directed towards creating stock. This creates a cycle where consumption, primarily from wage-earning households, is paid for by capitalist wages, which come from capitalist profits that depend on wages.

In graphical terms, while savings might equal investment (S=I), investment leads to savings (I → S). That is, future investment in consumable goods leads to profits, which lead to savings in a capitalist society.

Ironically, Kalecki, a dedicated communist, found himself disillusioned when he returned to communist Poland because the government wasn’t managing the consumption-investment trade-off as he thought it should through planning.

In a socialist economy, Kalecki found a similar problem — you can invest in many things, but returns come when someone else consumes that thing in a way that generates money. If you keep investing in things that aren’t generating returns, you have to write down the capital stock.

This is essentially what started to happen by the mid-1960s in the Soviet Union. There was significant investment in goods that weren’t fulfilling consumer demand, and consumers themselves didn’t have enough budget to spend on the basket of goods they wanted. This resulted in a cash overhang and capital assets that had to be written down.

The agents in my book — party officials, academics, and para-academics — were trying to deal with this disjuncture but kept hitting the wall. The fundamental issue was the misallocation of resources between consumer goods and heavy industry, creating an economy that produced goods people didn’t want or couldn’t afford, while simultaneously underinvesting in areas that could have improved living standards and economic efficiency.

Jonathon Sine: As I read the book, I was trying to understand your discussion of distributional issues. They sound like top-down party-state dictates about where money should flow. Are these entirely separate from issues like price reform and the other topics you extensively explore in the book? You provide an intellectual history of reformers discussing different approaches. However, it seems you’re saying they’re operating within a prescribed Overton window that precludes what you consider the fundamental distributional issues. How are all these elements related?

Yakov Feygin: Some reformers do address these distributional issues. Even those discussing price reform understand it as a way to tackle resource allocation. The interesting question is how they navigate within their prescribed space, which changes over time. From the vantage point of the Kosygin reforms (1964-1969), it might have seemed there was considerable room for change. Hindsight is 20/20, but in 1965, it wasn’t clear how limited the options were.

This is fascinating because it demonstrates that even in the Soviet Union, there were legislative politics within the party-state. More importantly, it shows that Soviet leaders were aware of trade-offs and alternative paths, even within officially sanctioned discourse.

The question then becomes — why weren’t these alternatives pursued? That’s the million-dollar question of the book.

I believe it’s a highly contingent issue. Until the late 1960s or early 1970s, there was a window of possibility for more extensive reforms. The fact that they weren’t implemented is itself a political decision.

The planned economy is not our wish; it is unavoidable or else everything will collapse. We destroyed such bourgeois barometers as the market and trade, which help the bourgeoisie to correct disproportions. We have taken everything on ourselves. The planned economy is as unavoidable for us as the consumption of bread. This is not because we are “good guys” and we are capable of doing anything and they [capitalists] are not, but because for us all enterprises are unified.

Jonathon Sine: Could you discuss some metrics used to gauge the economy’s deteriorating performance? How did people within the system assess this, and how would they have judged the success or failure of certain reforms?

Yakov Feygin: The assessment varied depending on whom you asked within the system. Khrushchev’s approach differed significantly from Stalin’s. Khrushchev believed Soviet economies could be directly compared to capitalist economies, including quality of life measures. He expected the Soviet Union to catch up with the United States in terms of living standards and individual goods usage and output.

This socioeconomic competition was seen as a way to avoid a third world war while demonstrating the superiority of the planned economy model. Khrushchev explicitly benchmarked against the United States, which hadn’t been done under Stalinism. Some who resisted comparing the two systems faced repression of their work and sometimes themselves.

As Khrushchev’s coalition began to crumble in the lead-up to his replacement in October 1964, there was a growing realization that his grand promises of achievement through pure mobilization, without relying on expertise, weren’t materializing. This realization helped create a political opening.

Additionally, the Soviet Union faced a political crisis in the mid-1960s, exemplified by the Novocherkassk massacre of striking workers. The promised prosperity wasn’t materializing. Due to a form of classical inflation not immediately reflected in price increases, more capital had to be written down. This eventually necessitated price hikes, particularly on deficit goods like meat and milk — items that were supposed to be in abundance, even surpassing capitalist economies.

This situation created a clear and widely recognized political crisis.

Jordan Schneider: I’m intrigued by this moment when Khrushchev suddenly decides to compete with the US on their own terms, forcing everyone to take an uncomfortable, critical look at the Soviet system.

On one hand, you have economists realizing they need to learn about American methods of measuring productivity to make comparisons. A few years later, it becomes evident that the trend lines aren’t converging but potentially diverging further than during the more coherent vision of the 1940s and 1950s under Stalin’s industrialization.

Yakov, was this Khrushchev’s only move? Was it inevitable that the Soviet Union would start building its legitimacy in comparison to the US? It seems like they could have promoted socialism’s merits without relying on such a materialist definition of success.

Yakov Feygin: That’s an excellent question. To frame it more clearly, it’s not just about a materialist definition of success. It’s about how to achieve the Soviet Union’s ideological goal, which was internationalist and global, with a Soviet state that had become a normal industrialized society in many ways.

Khrushchev’s answer was to move away from Stalin’s “inevitability of war” doctrine. The post-World War II generation of Soviet leaders wanted to avoid another war if possible, as detailed in books by Odd Arne Westad, Sergey Radchenko, and Vladislav Zubok.

Instead, the strategy became demonstrating the Soviet system’s power to develop a state and attract more countries to their bloc, even if those countries weren’t necessarily Leninist. Initially, there were efforts to reach out to European social democracies and the emerging “Third World.”

The idea was that if the Soviet Union could succeed, a world socialist system would emerge that everyone would want to join, creating a crisis within the capitalist system.

This approach, they hoped, would lead to a less drastic way of building global socialism. Khrushchev’s generation were true believers but wanted to avoid war and the harsh Stalinist approach. Their middle course was to build an appealing socialist modernity as an alternative to the capitalist economy. However, they struggled to figure out how to achieve this in practice.

Surpass England, Catch up to America 超英赶美

Jordan Schneider: Let’s take a brief detour. Jon, do you want to discuss how Mao adopted this “catch up and surpass” 超英赶美 concept from Khrushchev? It became part of Mao’s legitimacy package after the dramatic failure of the Great Leap Forward.

Yakov Feygin: That’s right — when Khrushchev declared the USSR would overcome the US at some point (“догнать и перегнать Америку”), the immediate Chinese reaction was to set their target as Great Britain, which I found quite amusing.

Jonathon Sine: Yakov, you mentioned that explicitly naming the United States as a competitor was forbidden under Stalin. When you read Chinese documents today, Xi Jinping and the Communist Party leadership very rarely make explicit comparisons with the US. They often speak vaguely about “encirclement” nowadays, but rarely talk about the US directly.

Yet there’s an interesting parallel — Khrushchev took the Soviet system from war mobilization under Stalin to a “peaceful systems competition,” a phrase he used explicitly. Now, Xi Jinping explicitly uses the phrase “systems competition” to define the current situation. Even though he is vague about what exactly the other system is, everyone knows what he’s referring to. The contemporary relevance really stands out to me.

Yakov Feygin: That’s fascinating. In China up until recently, and in the Soviet Union under Stalin, they never claimed to be as developed as the West. They would acknowledge being behind because they started later. They always compared themselves to pre-1917 imperial Russia.

Even when they did compare themselves to the United States after Khrushchev, they would say, “We’re not as developed, but that’s because the US has 200 years of exploitative development behind them. We’re showing what can be done in 20-30 years.”

Paying subscribers get access to the second half of the interview. We cover:

Surprising parallels between Khrushchev's Soviet Union and Xi Jinping's China in economic competition and party discipline

The hidden role of migrant labor in Soviet, modern Russian, and Chinese economies

Distributional challenges in China's economy today mirroring those of the late Soviet Union

How China's potential "middle-income trap" compares to the Soviet experience