Spies in NY, Ballpoint Industrial Policy, Chinese vs. US Horror Movies, Chinese Football

Friday bites!

Spies in Albany

Peter Mattis is the president of The Jamestown Foundation, served on the House CCP Select Committee, and co-authored “Chinese Communist Espionage: An Intelligence Primer.”

Today, Peter is here to discuss last week’s arrest of Albany operator Linda Sun.

[Linda] Sun in the Gears: The Unknown Casualties of Influence

On September 4, the US Department of Justice unveiled a criminal indictment of former New York state government staffer Linda Sun and her husband Chris Hu. The couple was indicted for acting as unregistered agents of a foreign power, fraud, money laundering, and other offenses stemming from Sun’s relationship with PRC officials at the New York consulate. If Sun and Hu are found guilty, the authorities will make public the details, methods, and consequences of their activities. As the debate about how to address Beijing’s interference in democratic societies reignites, such information is essential for gauging the appropriate response to this aspect of the China challenge.

The indictment describes numerous incidents in which Sun stripped out mention of Taiwan or prevented state officials from participating in Taiwan-related events. In one particularly egregious breach of trust, she also forged the governor’s signature in support of a visa application for visiting PRC officials coming to the United States. In appreciation of her efforts, Hu’s business received several contracts with PRC entities. The money “earned” from those ventures allowed the couple to purchase a 2024 Ferrari and multi-million dollar properties in Long Island and Hawaii. (To put that in perspective, Beijing paid General Lo Hsien-chi 罗贤哲 — the head of telecommunications and electronic information for the Taiwanese army — only six figures for classified information on Taiwan’s military and attempts to block US arms sales to Taiwan.)

Indictments and other court documents preceding a trial never tell the full story. The Sun indictment contains only the minimum information required to show that Sun had taken actions — sometimes on her own, sometimes at the urging of PRC officials — to further Beijing’s interests.

The millions of dollars in benefits that accrued to Sun and Hu, however, suggest that her impact went beyond changing a few lines in a speech or keeping the governor of New York away from Taiwanese officials.

If Sun was willing to scrub references to Taiwan and Uyghurs from a speech or block meetings with Taiwanese officials, what might she have done if a Taiwanese business reached out to the governor’s office? Would she have blocked potential investment in New York? Or, given recent cases where Chinese-American activists were spying for Beijing, how would Sun have handled complaints or concerns expressed by Chinese diaspora communities about CCP harassment and intimidation? Those communications could be buried just as easily as words could be struck from a speech. The distrust that has stemmed from local authorities’ lack of responsiveness to such harassment may, in fact, be a deliberate byproduct of the Party’s influence through proxies like Sun.

The view we have into Sun’s activities is limited by the scope of the federal charges against her — here, that she was acting as an agent, receiving and acting upon foreign direction. But Sun has a fifteen-year history of working in New York politics. With her experience, connections, and — as is evident from the indictment — awareness of her potential influence, Sun is likely to have informally advised others in New York politics outside of her official duties.

These activities almost certainly will not be a part of the trial — but uncovering the full story will be necessary to assess the extent of the damage.

Learning the full truth about Sun’s activities would require a long forensic investigation of Sun’s files, communications, and activities with the public, with companies, and with other New York officials. Such an investigation would also probably necessitate federal involvement — because the limited resources and potential embarrassment of New York may prevent the state from effectively conducting its own investigation. The rub, of course, is that the DOJ is investigating thousands of other cases involving Beijing’s espionage, technology theft, influence, and transnational repression — the DOJ doesn’t need to investigate Sun’s activities any more than is necessary to gain a conviction.

But identifying consequences is an important exercise for the authorities. The consequences of Linda Sun’s influence are still unknown as of yet. New York Governor Kathy Hochul called Sun’s activities “a betrayal of trust”; there may be others, especially in Chinese-American communities, who also had their trust in their state government betrayed. They need an opportunity for their stories to be included in our understanding of the case.

The debate rages on — how should the US counter Beijing’s foreign influence activities and diaspora policies? How can we ensure the crackdown is consistent with democratic values and doesn’t stoop to racial profiling?

This is not a simple challenge. Investigations are hard. Resources and qualified people are rarer than one would think. And in a democratic society, law enforcement should stay focused on illegality, not poking into every potential entanglement with the Party.

But knowing the real cost of Sun’s activities will be incredibly valuable — the facts of this case will frame our options for response. Beijing is engaging in a campaign of covert, corrupting, and coercive interference in our democratic society. Without a concrete impact assessment, it will be impossible to determine what kind of efforts are needed to counter this activity, and how aggressive those efforts should be.

We did a show a few years back on Peter’s book on Chinese spies with his coauthor. Have a listen!

Tech Chokepoint History: China and Ballpoint Pens

The following is a cross-post from Mary Hui’s excellent a/symmetric Substack.

The idea of technological “chokepoints” lurched to the forefront of the Chinese collective imagination half a decade ago when Washington slapped sanctions on two Chinese tech giants, cutting their access to US technology overnight.

The “ZTE incident” and “Huawei incident,” as the 2018 and 2019 episodes are known, forced a reckoning across Chinese industry and government: dependence on a geopolitical rival had grown so acute that a flick of a pen from halfway around the world could, at least temporarily, cripple two domestic technological crown jewels.

China has gone into overdrive to uncover and dismantle latent chokepoints and prevent new ones from forming. Beijing set up a national technology security system to better protect its high-tech firms. The government’s main science funding body launched an emergency project to study and solve the “chokepoint problem.” And state media published a list of 35 chokepoint technologies on which China urgently needed to reduce its foreign dependence.

Ballpoints and chokepoints

The humble ballpoint pen is a cautionary tale.

There is what’s regarded in China as a “classic” question of manufacturing: why can’t China make a ballpoint pen?

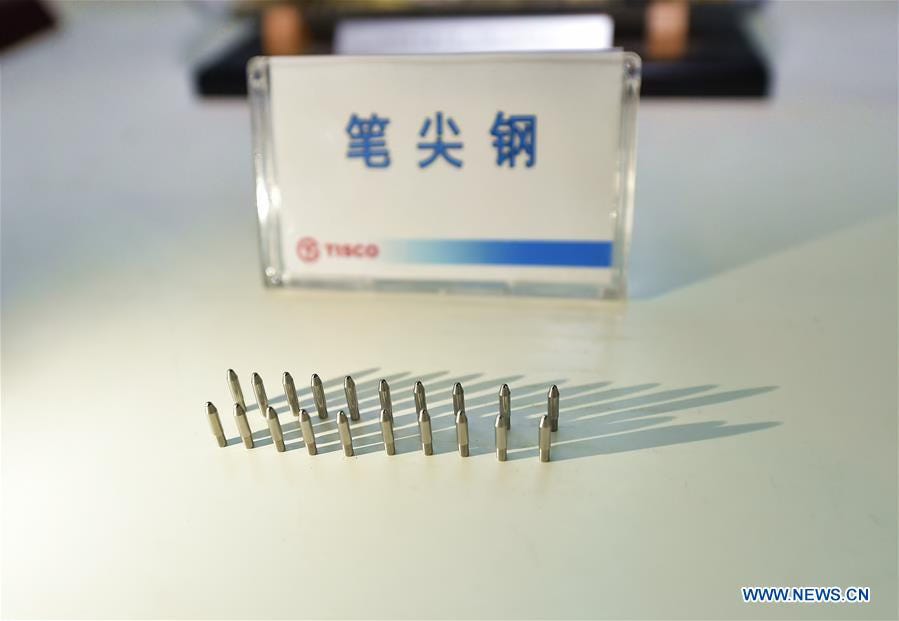

As it turns out, the ballpoint of the ballpoint pen — a tiny metal ball bearing that “mimics the action of roll-on deodorant,” rotating freely in a small socket to dispense a smooth stream of ink — is fiendishly difficult to make, requiring super precise machinery and high-quality steel made to very specific standards.

While China claimed a breakthrough in 2017, manufacturing a ballpoint pen all by itself and “ending a long-term reliance on imported [ballpoint pen tips],” as of 2021 the country was still reportedly 80% dependent on imported pens.

In fact, Chinese imports of ballpoints pens (comprising the ballpoint and ink reservoir) have more than doubled since 2017, from US$12 million to nearly $28 million last year.

As Lin Xueping 林雪萍, an expert on manufacturing technology, wrote in an article last year, it was one thing for a single Chinese company to make a technical breakthrough, and another to get the rest of the market to adopt it.

“Taiyuan Iron & Steel [太钢] finally decided to overcome the difficulties and finally made steel ball materials,” Lin wrote, referring to the Chinese steelmaker that made the pen tip breakthrough. “But domestic ballpoint pen manufacturers are unwilling to use it at all.”

There’s a larger point to all of this: China’s struggles with the ballpoint run in tandem with its efforts to make high-end machine tools.

Machine tools: a technical challenge or an economic one?

Machine tools are machines that make other machines. China is a leading producer of machine tools, accounting for about 31% the world’s output in 2021 (p.10, fig. 12) — ahead of Germany (13%), Japan (12%), the US (9%), and Italy (8%). But China is heavily reliant on foreign technology for high-end machine tools: in 2021, it was 91% dependent on foreign firms for the most advanced machine tools.

That’s in spite of a national-level initiative, dubbed “Special Project 04,” launched in 2009 to boost China’s capabilities in high-end machine tools. But still China has not quite cracked it.

Perhaps the problem is less technical and more economic. That’s the assessment from Lin, the manufacturing expert who’s also affiliated with a think tank run by China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology.

Top-notch machine tool beds, Lin reckons, demand very specific kinds of cast iron, with strict requirements for things like smelting method, casting temperature, and presence of trace elements. The problem is that demand from Chinese machine tool makers for this kind of cast iron is too small to make economic sense for iron foundries to work on developing the specialized materials.

“Made in China has two weaknesses: one is ‘can’t be made,’ which is a real technical chokehold; the other is ‘can’t be used,’ which is often stuck on non-technical barriers,” Lin wrote. “Ballpoint pens and cast-iron machine beds — both have stumbled for this reason.”

Implications for industrial policy

What lessons can we draw from China’s ballpoint pen travails?

Perhaps one is that just as the free market alone can’t solve certain problems — industrial policy may be more suited for tackling certain challenges than others.

In the case of China, it seems that its brand of top-down industrial policy has worked well for electric vehicles, batteries, critical minerals, shipbuilding, high-speed rail, and solar panels — but less so for semiconductors, machine tools, and ballpoint pens. One hypothesis is that the latter group of technologies requires a far more complex coordination of the industrial ecosystem. As such, the sheer force of the state’s will is more likely to run up against the fundamentals of market economics.

The upshot, for the US and the West, is not to parrot Chinese industrial policy, but to play to existing strengths. That means using government intervention to shape incentives, trigger certain behavior, and target market failures and distortions — but then stepping back to let the market solve for things.

China has long been dependent on imports of the tiny steel ball bearings that dispense ink from pen to paper. Beijing didn’t like that. In 2011, its science and technology ministry launched a national research project aimed at developing and industrializing “key materials and preparation technologies for the pen manufacturing industry.”

State-owned steelmaker Taiyuan Iron and Steel (TISCO) got the memo and got to work. Five years and 60 million yuan in state funding later, it declared success. Domestically made 2.3mm ballpoint pen tips began rolling off factory lines. TISCO’s shares jumped nearly 30%.

Chokepoint unblocked and chokehold broken? Not quite.

Today, China is still reportedly 80% dependent on imported ballpoints. Though TISCO did notch a technical breakthrough, domestic ballpoint pen manufacturers were reluctant to use the China-made ballpoint pen tips. The new steel balls didn’t work well with existing Swiss precision machine tools. They were not readily compatible with imported Japanese and German ink. And it made little economic sense for domestic steel mills to set up a new production line for such a tiny output of ballpoint tips.

In short, China made an isolated technical breakthrough on ballpoint tips that was of little use to the broader Chinese industrial system.

Pinpointing a systemic problem

Semantically, chokepoint implies a single point of dependence and failure.

But as the ballpoint pen story above illustrates, fixing a chokepoint requires far more than making a single breakthrough. Any solution has to be congruent with the existing network of suppliers and manufacturers, and their incentives, cost structures, and business models.

“The chokepoint problem involves the intersection of multiple supply chains and multiple nodes. It is extremely difficult to exhaust the problems simply from one industry or one industrial category,” writes Lin in his book, Supply Chain Attack and Defense 供应链攻防战.

“To tackle the problem, it is far from enough to just list the chokepoints,” he adds. “Chokepoint products are just the tip of the iceberg. Their underlying related factors below water can only be detected if there is a systemic understanding.”

There’s a larger industrial policy lesson here. Certain strategic and emerging industries require government prodding to kickstart, attain viability, or retain. But there are also lots of technologies where the market will always know far more than technocrats; just look at China’s wasteful ballpoint pen foray. The first step to breaking chokeholds is sorting out the real ones from the fake outs.

Chinese vs. Western Horror Movies

A translation from our friends at Weibo Doom Scroll.

A discussion on the difference between Chinese horror and western horror:

Western horror: You come home to see that your three-year-old son is dead, his guts are all over the floor, and your cat is licking up the blood. Chinese horror: You come home to find your cat is dead, its guts are all over the floor, and your 3-year-old son is meowing.

When you mention Chinese horror, the first thought that comes to mind is Grave Robbers’ Chronicles 盗墓笔记, where Wu Xie 吴邪 was in the cave, and he found Lao Yang’s 老痒 corpse and photo ID. But Lao Yang is outside the cave staring at him.

One is a sensory shock, one is a psychological shock. Chinese horror is better at leaving you with PTSD. Here’s an example. Western horror is like: you walk into a pizza store in a bad part of town, and just as you’re about to pay, you find the owner has a knife in hand, with a bloody piece of pizza in his mouth, staring at you with a furious expression before he leaps at you. You run and hide and finally manage to escape from him. Are you going to be scared of pizza stores from now on? Sure. But you’ll stop and check outside the store to see if the owner is a tiny, cute girl or a muscular guy before you decide whether or not you go in.

Chinese horror is more like: you go buy bread, and a kind old grandma hands you the bread and tells you with a smile, “Go on and eat it.”

You don’t think anything of it in the moment, but when you return to the street, everyone on the street turns to look at you with the exact same smile and tells you, “Go on and eat it.”

When you get home, your parents stare at you, smile, and say, “Go on and eat it.”

You’re freaked out and go to the bathroom to wash your face, and the you in the mirror smiles at you and says, “Go on and eat it.”

Even if nothing happens in the end, I think you’ll never go buy bread again, whether it’s a cute little girl selling it or an old grandma.

It’s really simple. Western horror makes sense, and Chinese horror is all about things not making sense. When things don’t make sense, you get a strong sense of dissonance and feel uneasy.

Here’s an example. Five people enter a haunted house and get attacked by a ghost. In the end, three people survive and get out, and two people die.

That’s very logical: go into a haunted house → get attacked → two people die → three people survive is a very complete line of logic. Everything makes sense, and it’s how Western horror stories work.

But if five people go into a haunted house and get attacked by a ghost, and six people walk out in the end, and everyone is really happy that they all survived and skip on toward home — that’s Chinese horror.

Right? Isn’t that freaky?

Because it doesn’t make sense.

It doesn’t make any sense that five people walked in and six people walked out.

Why does Chinese horror feel oppressive? Because your imagination goes wild when things don’t make sense. It’s basically you scaring yourself.

Does the movie director know what scares you? Probably not. But if you’re in charge of scaring yourself, of course you’re gonna get scared, because you know exactly what you’re afraid of.

Your imagination goes to your precise fears and you get freaked out.

Have you seen the classic horror movie Nightmare on Elm Street? Freddy kills people in their dreams, and people die when they are killed.

That’s very logical. Whether you have money or not, you die if you’re cut into pieces with a chainsaw.

It’s very bloody, but it’s not that freaky.

But in the classic Chinese horror movie A Wicked Ghost 山村老尸, does Aunt Mei 楚人美 walk around with a chainsaw? Does she cackle in people’s ear?

No.

They even play a piece of Yue Opera at the end, and that high-pitched singing sets your hair on end.

But as a piece of traditional Chinese opera, why would Yue Opera make you feel so freaked out? Why would it cover you in goosebumps?

Because it doesn’t make any sense.

When a lot of things that don’t make any sense come together, the conflict in logic makes you doubt yourself. And when you start scaring yourself, Chinese horror has won.

I saw a ghost story once that there’s a superstition that you can’t leave your shoes pointing at the bed, or ghosts will crawl into bed using the shoes. One night, the wife couldn’t sleep late at night, and while the husband got up to go to the bathroom, she kicked his shoes all over the room and then waited to see how he would react. But after the husband was done, he came back and started wandering around the bed muttering, “Where did the bed go?” When I read that, I literally felt a chill go down my spine.

A single line in Chinese horror can give me goosebumps for half a month. I remember a short story where a girl came home to find the power was out and the elevator wasn’t working, so she called her mom to come downstairs with a flashlight and help her up the stairs. Along the way, she chatted with her mom about her day at school like normal, and when they reached her door, her mom suddenly smiled at her and asked, “Do I look that similar to your mom?”

Alexa Pan — Chinese Song of the Week

This week’s song is Goalkeeper 守门员, by Chinese Football.

Chinese Football is a habit that’s hard to kick. Formed in 2011, the band tends to make light of their origin: guitarists Xu Bo 徐波 and Wang Bo 王博 met as fellow fans in Wuhan when there was “still a bit of punk feeling left” in the city. Their band name is as much a tribute to Illinois indie rockers American Football as it is a silly publicity stunt.

Self-described as “emo,” their style evokes equal parts nostalgia, apprehension, and hope. (For those who see music: sunlight dancing off shattered glass and dew.) The emotional songs come playfully packaged: the soccer motif pervades their first, eponymous, album, while later works borrow video game aesthetics and metaphors.

“Goalkeeper” hails from the first album. In a way, the song is as straightforward as the goalkeeper’s job, opening with a two-chord progression, melodies running back and forth in the penalty box. The guitars weave a net of sound, both more orderly and elastic than the typical wall, catching every kick of the drum. The lyrics, rich with soccer allegory and puns pairing Pelé (贝利) with paradox (悖理), describe a goalkeeper lost on the field, eventually leaving their post and moving forward. One could interpret this story as the band’s own: they’ve long aspired to “break out of Asia, step into the world, give it our all, leaving nothing behind.”

If you liked this song, catch Chinese Football on their upcoming North American tour.

Somewhat unrelated thought: shouldn't we be recycling discarded ballpoint pens?