Taiwan’s 2024 Elections: A Primer

The nuances of a three-way race, party primary snafus, Taiwanese voter concerns (beyond national security), modes of possible CCP interference, and the future of Taiwanese democracy

To discuss the rapidly approaching Taiwan elections next year, ChinaTalk brought on Kharis Templeman of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. He’s a genuine expert on all things Taiwan, especially its domestic politics.

ChinaTalk’s editor Nicholas and Kharis discuss:

The frontrunners’ profiles — Lai Ching-te 賴清德, Hou Yu-ih 侯友宜, and Ko Wen-je 柯文哲 — and what makes this three-way race different from previous elections;

Why the KMT’s nomination process was somewhat quirky this time around;

The importance of party unity, and why some Taiwanese political parties have failed to unify in past election cycles;

What’s on Taiwanese voters’ minds — beyond national-security concerns;

The CCP’s preferred winner — plus if and how any PRC-based interference may manifest over the coming months;

Why Taiwan’s election system is “unhackable”;

What to make of the spread of disinformation and hyper-partisanship in Taiwan’s domestic media;

And some pro tips on escaping the DC bubble and understanding the Taiwanese populace.

Transcript below or feel free to listen instead!

Surgeon, Cop, or VP?

Nicholas Welch: On January 13, 2024, the Taiwanese populace is going to head to the polls and choose their next president. President Tsai Ing-wen 蔡英文 has already served two terms, so there’s going to be a new president.

I’ll go over some of the facts about the candidates, and then you can fill in the interesting things:

For the ruling party — currently the Democratic Progressive Party 民主進步黨 — the candidate is Lai Ching-te. He is currently the vice president of Taiwan; before that he was the premier, also under Tsai. Before that he was the mayor of Tainan, a large city in southern Taiwan. And before that, he was in the medical field — a spinal cord expert, working in rehabilitation.

For the KMT 國民黨, or Nationalist Party, we have Hou Yu-ih. His career started in police — he was a high-ranking cop. He’s had some interesting caseloads, including dealing with a high-profile hostage negotiation rescue in Taipei, as well as investigating the assassination attempt of former President Chen Shui-bian 陳水扁. After his time as a cop, he was made deputy mayor of New Taipei City when Eric Chu 朱立倫, currently the KMT chairman, was mayor. And since 2018, Hou has been serving as the mayor of New Taipei City.

Lastly, we have a third-party candidate, Ko Wen-je. He’s a member of the newly established Taiwan People’s Party, or TPP 台灣民眾黨. He’s originally from Penghu, and his career also started, like Lai’s, in the medical field: he was an ER trauma surgeon. But then in 2014, he entered politics: he was elected mayor of Taipei as an independent, and served for eight years until 2022.

So that’s the background. What else do we need to know about these candidates?

Kharis Templeman: The first thing you’ve noted is that this is an open-seat race: we’ve got three declared candidates for the presidency, and none as the incumbent. So in that sense, it’s wide open.

Lai Ching-te is the candidate of the ruling party, the DPP, and he’s following in the footsteps of Tsai Ing-wen, who won two very large victories in 2016 and 2020. But he’s going to, I think, struggle a little bit to hold onto the coalition that Tsai built: he’s a bit of a different candidate than Tsai, and polling numbers are showing him quite a bit weaker than Tsai was in the under-forty demographic. For that reason, it’s actually hard to predict who’s going to win this next election.

In addition, there’s a three-way race: Ko Wen-je is the third-party candidate. Traditionally, over the past several elections, we’ve had two major party candidates, the KMT and the DPP. This time around, Ko is polling very well right now — and so that suggests that he may actually draw a significant share of the vote away from the two major parties. He has, I think, a non-zero probability of actually winning the election. And because of that, strong incentives for voters who really dislike one of the candidates to vote strategically for one of the other two.

I expect there to be a lot of volatility in the run-up to the election in January in the polls, and a fair amount of appeals by the candidates to convince voters that they themselves are the second-best alternative to a candidate who’s hopeless. So I think there’s going to be some major shifts in the polls over the next few months, based on who voters themselves see as the most valuable.

Nicholas Welch: Something interesting that listeners should know about Taiwan’s electoral system: a presidential candidate doesn’t need a strong majority — over 50% — to actually win the presidency. They just need a plurality. So three-way races can actually be very important in determining who will succeed.

This happened in 2000 when the KMT’s candidate, Lien Chan 連戰 and James Soong 宋楚瑜 had a falling out; James Soong ran as an independent, and he split the vote of people who would normally want to vote for KMT.

And Chen Shui-bian, although he received just under 40% of the vote, still won more votes than the other candidates — so he won the presidency.

Do you see something like that occurring in 2024?

Kharis Templeman: I think it’s more likely than not that we have a minority winner — in other words, no candidate crests 50% of the vote. If it were just a two-party race, or if Ko were just a fringe candidate who wasn’t polling more than, say, 5% of the vote, then we might still have a majority winner. But I think Ko is strong enough to hold on to a crucial sliver of the electorate that would pull down one or both of the other candidates well below 50%.

Nicholas Welch: Could you help me make sense of what the TPP’s platform really is? Ko has branded himself as the third way: “If you don’t like the pan-Blue KMT camp, and if you don’t like the pan-Green DPP camp, then you can vote for me.”

But the TPP was founded in 2019 — it’s very new. What exactly is the TPP’s platform? And what could we expect if Ko really won the presidency?

Kharis Templeman: The TPP started out, really, as a personal vehicle for Ko to exert influence in national politics. So the creation of the party in 2019 was a decision of Ko: he pulled some people into the party with him — but it was very much the party of Ko.

And they deliberately avoided taking kind of a clear stance on cross-Strait relations or on many of the other policy issues that divide the parties in Taiwan today. Ko’s rationale for that was that he’s a doctor, he’s very pragmatic: he just sees problems and solves them; you just need to use common sense to address whatever problems are facing the country. And he’s the candidate of common sense, and the other two parties spend all this time engaging in partisan fistfights, and so he won’t be that.

In Taiwan, every color signifies a political significance. The TPP is not green or blue. They’re aquamarine — they’ve literally chosen the color right in between green and blue to symbolize that they’re the centrist alternative to both camps.

Frankly, even now, I don’t know that I could tell you exactly what the TPP stands for, what Ko would do if he became president.

When he came into office in 2014, he was actually backed by the DPP; the DPP supported his campaign, and so he was originally characterized as being part of the green camp in Taiwan. More recently, he’s drifted toward the blue end of the spectrum. And the conventional wisdom is that his candidacy is likely to hurt the KMT more than the DPP now.

His talking points on cross-Strait relations have been all over the know. He will criticize China in very harsh terms on one day — and then talk about how the two sides of the Strait are part of the same family in the next day. So I think very hard to pin down on a lot of these issues.

The Backstory Behind Taiwan’s Primaries

Nicholas Welch: I’m also curious what to make of the KMT’s candidate at the moment. The KMT nomination process was interesting this time around: they forewent opening the primaries to elections. Before, Hou and Terry Gou 郭台銘 were the frontrunners for the KMT nomination — and then chairman Eric Chu just nixed the whole process and personally selected Hou.

And we’ve seen reports that, for example, Eric Chu has vehemently denied suggestions that maybe Ko should join Hou’s ticket and they should run together to make sure they don’t split the vote. But also: Ko is currently pulling higher than Hou, which is a little bit strange for a country that’s been so institutionalized with two parties.

And the other factor I think about here: in the 2022 midterm elections, the KMT actually performed quite well — in fact, they performed so well that Tsai Ing-wen, who was the chairwoman of the DPP, stepped down.

So I’m not sure how to make sense of the KMT’s odds going forward, and I’m not sure what’s driving these polling and electoral shifts. Can you help shed light on this all?

Kharis Templeman: Let’s talk about the nomination process in the KMT first, because that is, I think, not well understood, even within Taiwan.

The challenge that the major parties in Taiwan have had for years is how to identify the strongest general election candidate when they choose a nominee. If you just hold a vote of party members, you may get a candidate who’s much more extreme than the median voter in the electorate. Those candidates can appeal to the base, but they can’t appeal to swing voters — and so they do very poorly in the general election. (We’re familiar with this problem in the US in our own primary system.)

Both the major political parties in Taiwan have experimented with ways to mitigate that problem. So rather than having a party primary that is restricted only to party members, they open it up to a larger swath of the electorate. Or increasingly, over the past, say, fifteen years, the parties have moved toward polls as a significant part of the nominating process: they’ll do a poll of the electorate and see which candidate polls the best against a common opponent.

The problem with that: on the one hand, you do generally get the candidate who appears to be the strongest in the general election. But on the other hand, polls can be manipulated. There are all kinds of — what we would normally think of as — fairly technical questions about how to design a sample, how to weight that sample so that it represents the electorate:

Do you use cell phones as well as landlines?

Do you use different polling companies, or all the same?

Do you poll over just one day or over a two-week period?

And most importantly, which candidate do you put your own party’s potential nominees up against in the poll? So for instance, do we put Hou up against Lai and Ko, or just Lai?

And then if there are alternatives, do we put those other candidates up against Lai and Ko and alternatives?

All of those can actually fundamentally shift the result of the polls in a certain direction — so both parties have become less enthusiastic about using that sort of polling mechanism to choose their candidates.

Another problem they’ve run into — especially for local-level races — is that there’s actually a way to rig the system. There are credible rumors of candidates actually renting out an entire building, plugging in 1,000 phone lines into a building, and then having their people in the building answering the polling calls that they know are going to come — basically biasing the polling results toward their favorite candidate. I don’t know how you screen for that. If a candidate really does have the kind of resources to do that, that’s a way to rig the poll results.

And another problem — and the one that became really apparent in 2020 — is that if you’re polling the entire general electorate and they know there’s a poll that might decide the other party’s nominee, a Green polling company is going to get some Blue voters, and a Blue company is going to get some Green voters in their sample, if it’s a representative sample.

And so if you are, say, a member of the KMT, you want to nominate the most extreme DPP candidate, because he’s the easiest to run against — and so you say, “Oh, I really love this one guy.” Or in 2020, a lot of green voters apparently said, “No, you really need to nominate Han Kuo-yu 韓國瑜; we think he would be the best candidate.” So the KMT ended up with, I think, a less-appealing candidate than they otherwise could have in that race.

So that’s the background story here for why the KMT in this election decided not to use the polling mechanism.

In 2022 local elections, they actually tried out an alternative in which they negotiated at the local level, and the party executive committee brought all the prospective candidates together, looked at polls privately but did not announce that they were going to do that, and also just informally canvassed local party members to figure out which of the candidates appeared to be the strongest one. And then the party chairman had the authority just to handpick the nominees after that process.

The outcome of the 2022 election was so favorable for the KMT that they thought, “That actually looks like a good method for 2024 as well. Let’s basically repeat that process for the presidential nomination.”

The problem they’ve run into, of course, is that the rules were very opaque. And the losing candidates — the candidates who didn’t get picked, especially Terry Gou — were really unhappy with that. And the KMT leadership couldn’t really demonstrate to everybody that this was a fair process.

And so it now sounds like Gou is still trying to overthrow the process and get himself nominated as the KMT candidate. I think that it’s unlikely that will happen — but there is not unity in the party now behind their nominee because of disputes over that process and discontent with the way that Hou was chosen. So that’s the problem.

And I should note: the DPP avoided this problem only by excluding every other candidate except Lai himself. He was able to clear the field even beforehand, so they didn’t have an actual contested process to choose their nominee.

In 2020, Lai actually challenged Tsai Ing-wen — but Tsai used her control of the party to delay the primary and then structure the rules in such a way that she had the best chance of coming out on top. And so there were some bitter feelings at the end of that process as well. It’s just that the DPP is generally much better at closing ranks when you get close to the election than the KMT is.

So neither party has, I think, come up with an ideal way to deal with this problem. And every election cycle, they’re still experimenting with new solutions to the challenge.

Nicholas Welch: You mentioned before that Lai Ching-te directly challenged Tsai Ing-wen in the 2020 election, but the DPP was able to maintain a semblance of unity, ultimately, because Tsai then chose Lai as her vice president running mate.

And to his credit, Gou, at least on Facebook, has endorsed Hou Yu-ih as the KMT candidate — but that only goes so far.

Kharis Templeman: And he’s not acting like he wants Hou to be the nominee. Gou is showing up publicly at Ko Wen-je events. He did the bare minimum to endorse Hou at the end of that formal nomination process — but there are lots of rumors within the KMT right now that he’s still trying to overturn the nomination. The party actually hasn’t formally selected Hou as their candidate — that’s going to take place on July 23. And so there’s still an outside shot — or at least Gou seems to think so — that he might be able to lead some kind of rebellion within the KMT to overrule the party chairman and get himself selected as the nominee. [Update: After our chat, Hou was indeed formally selected as the KMT’s candidate.]

The difference with 2020 was that Lai Ching-te — on day one after the nominee was announced — endorsed Tsai, didn’t criticize the process, accepted his defeat, and said, “We have to unify to defeat the KMT and China.” Lai’s rhetoric really helped unify the party — he really could have really messed things up for the DPP if he’d refused to support Tsai.

So, in this cycle, Tsai has supported Lai as her successor. There are credible rumors that she would have preferred to see somebody else — but Lai was able to build a critical, decisive coalition behind him within the DPP, and as a result, Tsai is fully supporting his campaign now as the DPP’s nominee. She’s not trying to maneuver behind the scenes to force him out and pick someone else.

Crossroads of Discontent: Quality of Life vs. Cross-Strait Dynamics

Nicholas Welch: And beyond party unity, what are the issues on which the Taiwanese electorate is considering in choosing a candidate? If we’re in the DC bubble, we’re just thinking, “Which candidate isn’t going to push Xi Jinping’s buttons? or, “Which one is most likely going to maintain the status quo?” or, “Which one’s going to bolster the military the most?”

But Taiwanese voters have a lot more issues on their minds. They might be considering slow Q1 economic growth this year; or there have been some pretty serious droughts in the southern part of the island.

Can you speak to what are the factors that are going to drive the average Taiwanese voter?

Kharis Templeman: Well, cross-Strait relations is always the headline issue — and it’s the issue that most clearly divides the parties and the candidates.

But underneath that headline, there are some serious issues — I would call them “quality of life” or “cost of living” issues — that have left a sizable chunk of the electorate dissatisfied with eight years of DPP governance.

The cost of housing right now is astoundingly high in Taipei and the surrounding areas — so it’s just impossible for anybody entering the job market to even contemplate buying a house at any point in their future life, if they’re living in Taipei or nearby (unless they’ve got help from their parents).

And so the prospects of actually getting a job, buying a house, getting married, starting a family — all of that is pretty daunting if you’re a young person in Taipei right now.

And wages in Taiwan are also quite low, even relative to the regional standard. They’re quite a bit lower than in Korea and in Japan, and they haven’t really gone up at the same rate as economic growth over the last eight years.

And so there are a lot of frustrated young people in Taiwan right now, where they feel like that deck is just completely stacked against them.

They can find a job, but it’s not going to pay them much.

The cost of living keeps going up.

Inflation in Taiwan — like in most of the world — has been quite high over the last couple of years; it’s eating away whatever kind of gains they can make in their salary.

And the DPP government eight years ago — when the DPP was running to take over from the KMT — criticized the KMT on all of these issues. But for a lot of young people, things have just gotten worse over the last eight years.

So I think there’s a latent unhappiness with the incumbent party that is creating some real headwinds for Lai Ching-te in the coming election. I think he’s going to struggle to do anywhere near as well as Tsai Ing-wen.

Part of the challenge is that he’s the candidate of the ruling party: he’s Tsai Ing-wen’s vice president; he was formerly premier; he’s very closely associated with the Tsai government in voters’ minds. If everything in Taiwan were going well, he could make a credible case, “Vote for me: I will keep things on the right track” — and he could, I think, make a pretty strong appeal to voters.

But instead he needs to promise to fix a lot of problems that people are worried about — and he’s going to have a hard time making that case, because he was premier, he was in a position to fix it, and the problems didn’t get fixed.

And so if you vote for Lai, for a lot of voters it’s an endorsement of the status quo, the way things are now in the domestic economy.

So I think those issues, especially among younger voters, may create an anti-incumbent trend in the electorate.

Nicholas Welch: Speaking of younger voters: one policy change that DPP made with respect to young people is extending the mandatory military conscription period from four months to twelve months.

And interestingly, Hou Yu-ih has said that he does not support this, and if he were elected president he would keep the mandatory conscription period to four months.

You can make lots of arguments on both sides: I know people in the DC world don’t like the signals that keeping military conscription short would send to their willingness to fight or to America’s role in such a fight. But people in Taiwan may say, “I don’t like standing in line and cleaning barracks toilets for four months, so why would I want to do that for twelve months?”

Could you speak to that concern of all?

Kharis Templeman: I should clarify that Hou floated a trial balloon where he said, “I want to reverse this policy” — and then a day later he walked it back. So it appears to be the case now that Hou supports the extension of conscription to one year, and that maybe there’s some division within the KMT on this issue as well.

Regardless, it’s not a good look for him in the eyes of Washington DC, where there’s strong support and actually a lot of pressure on the Taiwanese government to reform the military, and to extend conscription as one part of a much larger set of changes.

As you might imagine, young people in Taiwan are not particularly enthusiastic about the idea of having to spend a year of their lives in the military. The support for the change tends to be higher among older people who don’t have to bear the burden of it now.

But it’s another issue that could potentially undercut the DPP’s support among young people.Tsai Ing-wen, to her credit I think, decided that it should be an important priority for her government to extend conscription just for national-security reasons, even if it came at some kind of a political cost. But the DPP may end up bearing part of the cost of that decision.

And in fact, one year is probably not long enough. Taiwan used to have a two-year conscription, and people who’ve looked at this issue in the United States have almost universally said that Taiwan needs to be at a minimum of two years again to send a signal to Beijing that they’re well-prepared to fight off an attack — and as a signal to the US that the Taiwanese are committed to their own defense at the level that the US is.

The hope among a lot of the people I talk to in the US is that this is a first step, a down payment on an extension of conscription to two years and maybe more.

Whoever the next president is in Taiwan is going to have to deal with that contradiction — where voters, by and large, don’t want that extension, and Taiwan’s largest patron and most-important security partner does.

If the CCP Could Cast a Vote…

Nicholas Welch: Let’s talk about China. What does the CCP make of all of this?

I think historically, it was probably pretty safe to say that the CCP much preferred the KMT candidate. The KMT was much more on board with the idea of unification under some terms.

But this time around is a little bit different in the sense that all three candidates, including Hou Yu-ih, have rejected the “one country, two systems” unification proposal.

Will that influence how China sees cooperation with the future Taiwanese government? Do you still think they would prefer Hou over another candidate?

Kharis Templeman: Yeah, I think generally they would prefer the KMT to win. They certainly don’t want the DPP to win — I think that’s clear.

They just don’t trust the DPP at all. They have a paranoia about the DPP — that Tsai Ing-wen herself tried to overcome. She made a lot of rhetorical concessions in her inauguration speech when she came into office that were intended to try to reassure Beijing that she would not support Taiwanese independence, that she would not try to separate Taiwan from China. And Beijing’s response was, “That’s not good enough. You need to go further.” And politically, it was impossible for her to go further without losing most of her party.

So there’s just a fundamental, irresolvable conflict or difference between the DPP’s view of the cross-Strait relationship and Beijing’s view.

And the KMT has had some difficult relations with Beijing, but there’s fundamentally a level of trust and understanding between the two sides — between the KMT and the CCP — that doesn’t exist between the CCP and the DPP. So I think, all else equal, they would definitely prefer a KMT candidate in office. They feel like they can at least work with someone from the KMT — the DPP is just hopeless, and they need to squeeze the DPP and try to undermine them at every turn.

The real wild card here is actually Ko Wen-je. As mayor, he was able to travel to the mainland and speak in Shanghai at the Cross-Strait Forum. And he’s used some phrases in the past that Beijing has reciprocated and adopted: there’s a phrase about both sides belonging to the same family, and Beijing actually started to use that phrase in some of their official statements about the two sides of the Taiwan Strait. That was, I think, a positive signal that they saw Ko in a different light than they would see a DPP candidate.

More recently, though, Ko has been quite critical of the CCP. And he’s also got this background as a physician who came into electoral politics with the backing of the DPP — so I think he’s still a bit tainted by that in Beijing’s eyes, and so it’s not clear to me what Beijing would do if he were actually the president next year. I think a lot would depend on what he says over the next six months, and then what he says in the run-up to his inauguration if he is the president.

The KMT is a known quantity — from the CCP’s perspective, it’s far preferable to dealing with the DPP. So all else equal, they would prefer that Hou Yu-ih win this election.

Nicholas Welch: Do you think that China will attempt to influence the elections in any way to achieve that outcome?

I mention that because they’ve been known to shoot themselves in the foot before:

In 2016, Chou Tzu-yu 周子瑜, a member of the K-pop group TWICE, was forced by her pathetic employer to make this groveling apology for holding a Taiwanese flag in a music video for about two seconds. And when they polled people in the 2016 election, over a million voters were aware of the issue at the time. And of course, Tsai Ing-wen won quite easily in 2016.

Then we have 2020: the protests in Hong Kong the previous year put the final nail in the coffin of “one country, two systems” ever working. I think people became very skeptical of cross-Strait cooperation. And once again, we saw Tsai win quite easily.

China may view that election history differently, or the reasons for the outcomes differently. But do you think that the CCP will try to interfere in this election?

Kharis Templeman: I think the smart move for the CCP — if they really do want the KMT to win — is to be quiet and to do as little publicly as possible to try to influence the outcome. They have, as you noted, a repeated history of shooting themselves in the foot, of doing something that causes a backlash against their preferred candidate or positions. And so I would expect them, over the next few months, to actually dial back some of the military pressure on Taiwan.

Some of your listeners may know this: they are already lifting some of the arbitrary bans on Taiwanese agricultural exports to the mainland, and they’re doing this in a very piecemeal way. But they are trying to signal that, if the Taiwanese voters choose the China-friendly candidate, you can expect more of these concessions in the economic realm.

So I think the most likely strategy for them is to try to dial back some of the explicit threats against Taiwan and focus more on the benefits that Taiwan might gain by electing a more China-friendly candidate president.

That said, the CCP is a big, unwieldy bureaucracy, and it’s conditioned to say and do things that can often be very tone-deaf in the Taiwanese political environment. The Chou Tzu-yu example that you mentioned — I don’t think there was any chance that was planned by the CCP. It was something that bubbled up from a low level, probably a bureaucrat or somebody trying to influence this group. And it just so happened that their long-standing insistence on artistic groups endorsing the one-China principle meant she had to apologize, and it was on TVs in Taiwan all day during election day. I don’t think that was at all intended by the CCP.

So there could be something totally unintended that pops up in the last days before the election that really triggers a lot of anger toward the PRC and motivates Taiwanese voters who are on the fence to swing toward the DPP and away from the KMT.

I think that the strategically most-sound approach is for the CCP to focus on the benefits that Taiwan would get and to dial back a lot of the overt military and diplomatic pressure. But they could do this very carefully over many months, and then suddenly have it blow up in the week before the election as well. It’s going to be exciting. Stay tuned, folks: it’s going to be a fun few months to follow.

Low-Tech, High-Stakes

Nicholas Welch: Also regarding election interference: something that I found really interesting when I was taking your classes is that Taiwan’s election system, in your words in an academic paper, is “unhackable.” It has some really interesting and notable features which make it quite resistant to interference.

I don’t think very many people know how Taiwan’s elections actually operate on the day of — could you talk about what makes Taiwan’s elections different?

Kharis Templeman: Sure, let’s talk about that.

The critical thing here is that Taiwan’s voting and counting is very low-tech and very transparent:

The voting is done via paper ballots.

There’s a large number of polling places relative to the size of the electorate.

The rules are very standardized throughout the island — they’re open from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. on a Saturday.

There’s no absentee balloting, and there’s no early voting — so for a vote to count, it has to be cast between 8 and 4 at the polling place that a voter is assigned on Election day. That’s it.

So right away, you screen out a lot of the things that complicate American elections, like mail-in votes that arrive a week later, or questions about whether the signature on the ballot or the mail-in vote was actually accurate or not. The Taiwan system has none of that. It’s very simple that way.

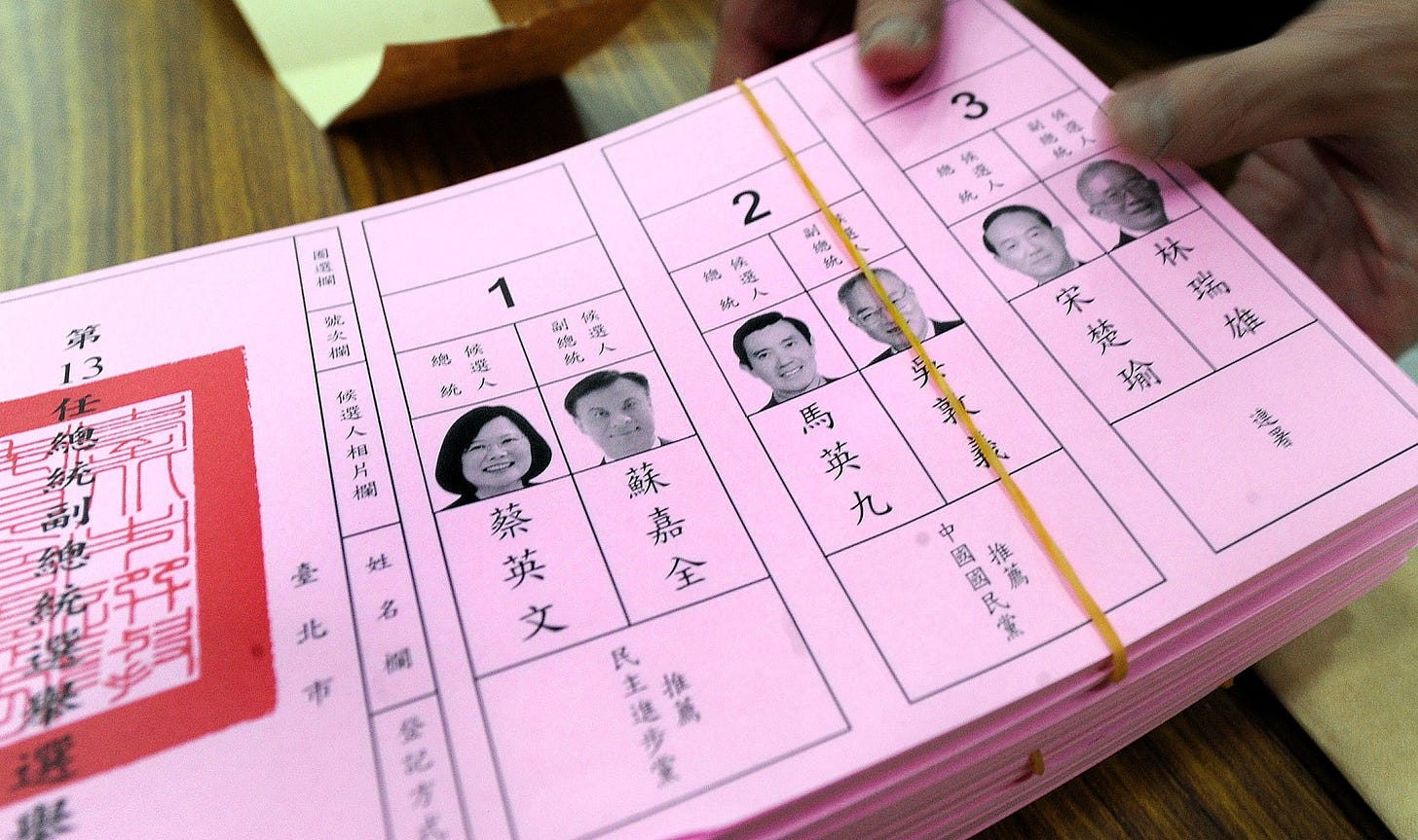

It also has a lot fewer races on the ballot than the US does. In each race that is being chosen, the voter gets a separate ballot for that race. So in the general election next January, there will be 1) a presidential ballot, 2) a district legislative ballot, and 3) a ballot for the party list. So they will get three pieces of paper.

The ballot is very simply designed: a picture of the candidate, the candidate’s name, and their party. And there’s a place to stamp your vote for that candidate — the stamp is a special symbol, and you have to use that stamp in the voting booth to cast a valid ballot.

Once that ballot is stamped, it’s just dropped in a box in the middle of the polling station and it sits there until the end of the day.

After 4 p.m., they close up and then immediately rearrange the room: the same poll workers who’ve been monitoring the vote the whole time then do the count in public view of everyone; so it’s actually done at the polling station immediately after the polls close.

You typically have about a dozen poll workers there calling out each vote, picking it up, looking at it by hand, calling it out, and recording it. And anybody who wants to watch that count can actually come into the polling station and be in a position where they can observe each vote being counted. So if you have any concern that there may be miscounts or ballot stuffing or votes being tossed away — any individual, even a foreign observer, can go in and just watch the count and reassure yourself that they’re actually counting accurately.

The last thing that’s great about this system is — because it’s done at the polling place using these paper ballots and there’s no absentee or early voting — the vote is done very quickly: It’s usually completed within two to three hours after the polls close. So they are in a position actually to announce the winner, say, five hours at the latest. And they typically certify the count — every single vote that’s cast all throughout the Republic of China on Taiwan — that whole process is certified by the next day.

To an American, that’s amazing, right? I think we’re still counting votes in California six months after the election, or it feels that. It takes a long time to get all the votes counted. Here in Taiwan, it’s very fast — as a result, you know the winner.

And the vote count also is very accurate. In some cases, there have been very close races, and they’ve had to go back and do a recount. The number of votes that change is typically in the single digits, maybe double digits — but it’s very, very accurate. And then the spoiled ballot rate, too — that is, votes that are thrown out as invalid because somebody stamped two boxes or they signed their name to the ballot — the spoil rate is about 1%. It’s significantly lower than in the US.

So if you wanted to try to manipulate the results, you would have to do it on a wide scale under the full view of all of these ordinary people coming in to watch the count. In that sense, in my view, the count is almost impossible to hack.

Blue Screens and Green Screens

Nicholas Welch: So it sounds as though the votes themselves, the election system itself is really hard to manipulate.

But that, of course, doesn’t address the media scene in Taiwan, which is quite hyperpartisan and actually surprisingly prone to spreading misinformation.

For example, even this year, one story that caught fire was that the US had a so-called “plan to destroy Taiwan” — that in the event of some contingency, the US would just eliminate our interest in Taiwan by destroying the island wholesale. This, of course, is fake news, but a lot of people bought onto it, and this was broadcast in prominent networks.

Another story which spread was about a US evacuation plan: in the event of an invasion, how would the United States evacuate American citizens who are on the island? And people considered this story to be an indication that the US had no resolve to defend Taiwan whatsoever, that they were already planning for defeat.

So these kinds of stories tend to stick in Taiwanese media for some reason. What can we make of all this?

Paid subscribers get access to the rest of our discussion, which includes:

The unique pressures that Taiwanese journalists face, especially during elections season;

To what extent and from which sources we can expect disinformation in Taiwan over the coming months;

How mainstream DC rhetoric regarding a future invasion of Taiwan could play into the KMT’s hand — and possibly the CCP’s;

What US delegations should do when they visit Taiwanese politicians — and what you can do to better make sense of what matters most to the Taiwanese populace.