We recently hosted two fantastic guests to discuss the rapidly approaching 2024 Taiwan elections.

Voice for the pan-Green populace is Lin Fei-fan 林飛帆, currently a board member of New Frontier Foundation. He was previously the twenty-second Deputy Secretary-General of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), spanning across both Tsai Ing-wen’s 蔡英文 first and second terms. He’s also well-known for leading the Sunflower Student Movement in 2014.

And voice for the pan-Blue crew is Lu Yeh-chung 盧業中, a professor in the Department of Diplomacy at the prestigious National Chengchi University 國立政治大學. He received his PhD from George Washington University, and his research specializes in international relations theory, US-China diplomacy, American foreign policy, ethnic conflict, and nationalism. He has advised several Taiwan government ministries on foreign policy.

(Disclaimer: the views expressed by both of our guests reflect only their own, not the views of their institutions or universities.)

Taiwan and China — Part of the Same Family?

Nicholas Welch: I have a number of friends from mainland China (who’ve never been to Taiwan), and if I were to ask them about the Taiwan issue, odds are they would say something like, “Listen, unification is inevitable, and it’s the right course of action — not because of history or nationalism or some kind of legal argument, but because we’re all part of the same family 兩岸一家人.”

So my question to both of you is, “Are you?”

Lin Fei-fan: Well, I can understand how Chinese people think about their relationship with Taiwan, since many mainland Chinese probably don’t have the chance to come to visit Taiwan and to experience the similarities and differences between Taiwan and China, or to understand how the Taiwanese identity’s been formed.

But I think it’s democracy that changed our whole understanding of ourselves. It’s the democratic process that helped us to form our new identity. That process helped people to understand, “Yes, I’m a citizen. I’m a citizen living in Taiwan. I can have a choice. I can vote on our parliamentary leaders. I can vote on our presidency directly.”

So I think that democracy helped us to recognize ourselves as Taiwanese — and I think that it’s not just the identity differences, but also the regime differences between Taiwan and China that put us on totally different ways of living.

Nicholas Welch: Professor Lu? — what would a pan-Blue person say in response to the question: 兩岸一家人 — are we part of the same family on both sides of the Strait?

Lu Yeh-chung: Pan-Blue supporters usually share the view that — in terms of cultural ties, religious ties, and even history — yes, we are very close to each other across the Taiwan Strait.

But in the meantime, I think this is a question about sense and sensitivity — that is, it’s all about interactions, cultural ties: we can engage or interact with each other. It’s quite important to know that, especially for the KMT leadership and also for the presidential candidates, they seem to be adopting a rather pragmatic view on this.

And in the meantime, we all know that there is rising nationalism in China right now — and also that the top leaders in China still want to unify Taiwan “by all means.” So for KMT supporters, we know that if the KMT presidential candidate right now becomes the president in the near future, we need to be very cautious about the interactions across the Taiwan Strait.

Some people would say the KMT is a pro-China party, pro-unification party. But my take is that, as a perspective from academia, the KMT is the political party which knows China better.

The KMT has the experience interacting with China. And learning from those experiences, we all know that defense, dialogue, and de-escalation — these are the key strategies Taiwan should adopt to sustain and secure ourselves.

Nicholas Welch: Definitely — that seems consistent with what the KMT has said for a long time.

I found this quote from a book written by KMT politician Shao Zonghai 邵宗海 in 1998: 兩岸問題的本質絕非黨派鬥爭,國土之爭,而是製度與生活方式之爭 — in other words, “The essence of the cross-strait issue is definitely not a partisan struggle or a struggle over land. Rather, it’s a struggle between systems and a way of life.”

That sounds very consistent with what you were talking about as well. But back to Fei-fan’s point from the DPP perspective: even if you were to acquiesce that we share common ancestry and culture, the difference in regime can’t be understated.

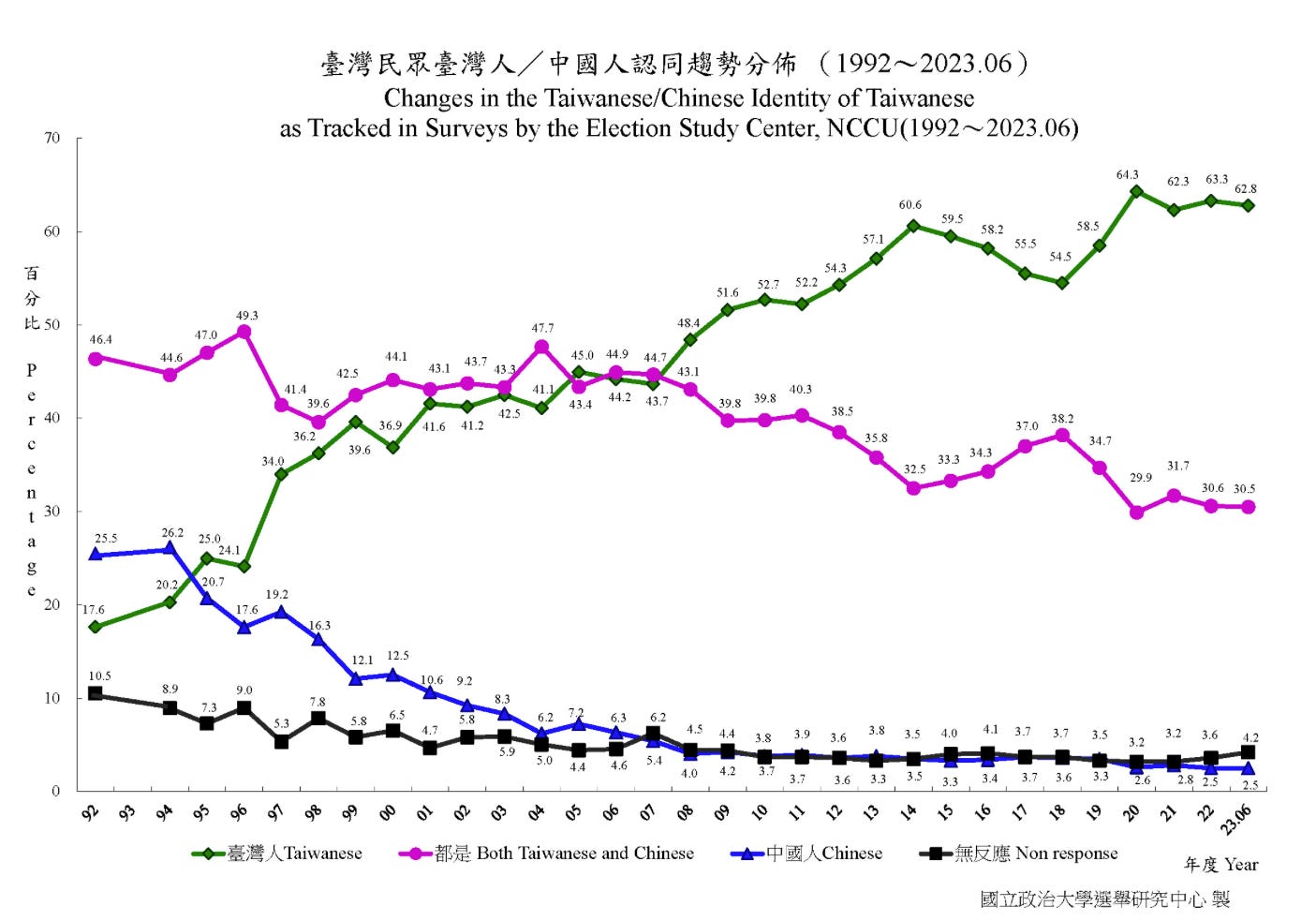

Lin Fei-fan: If you look at the polling right now, if you ask Taiwanese people about their identity, I think a very clear majority of Taiwanese people recognize themselves at “Taiwanese.” But if you look at the polling that asks people, “Would you recognize yourself as Chinese?” there are only 2.3% of people in Taiwan that recognize themselves purely “Chinese.”

So that number, to be honest, is quite striking for Beijing: not very many people recognize themselves as purely Chinese. If you ask Taiwanese, “Would you recognize yourselves as both Taiwanese and Chinese?” some data show that there is 20-something percent of people who recognize themselves as both Taiwanese and Chinese — but that’s based on cultural or ancestral similarities.

So to be honest, from our point of view, the shared culture between Taiwan and China is not a basic criterion for the two countries to think about their common future. There should be more discussion about not just identity, but also our way of life and the political system we believe in.

In terms of policies toward China: I respect what Dr. Lu has shared, that the KMT has its own so-called “3D policy” — defense, dialogue, and de-escalation — but to be honest, in the past couple of years, we have been seeing that the defense efforts of the DPP administration have been facing challenges by the KMT. Even some weapons purchases and indigenous weapons-system development are also being questioned by the KMT. And our strategies — like our asymmetric strategy — are also being criticized by some KMTers. So it seems that there are different understandings of our defense strategy between the KMT and DPP.

And I believe that, if you ask the KMT, “What is the priority of the 3D policy?” — from our understanding, they put dialogue, rather than defense, on top. They probably would say, “We can break even — we can do defense, dialogue, and de-escalation at the same time.” But it seems to us that, in the past, especially during the Ma Ying-jeou 馬英九 period, the KMT put so much focus on purely dialogue, rather than developing our defense systems.

So I think the DPP right now is noting the imbalance between the two militaries — the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and our Ministry of National Defense (MND) force — so we know what’s at stake: we need to put more focus on our defense development, rather than purely focusing on dialogue.

Lu Yeh-chung: I think Fei-fan explained their position very well. But let me lay out some facts here:

In the past almost eight years, the KMT has been the opposition party; and in the Legislative Yuan, the opposition has the duty to watch over the budget — the whole budget, not only defense budget. We all know about, for example, Taiwan’s indigenous submarine tests. Which administration initiated this plan? That was Ma Ying-jeou. So as you can see, for the 3D strategy, the KMT already put defense as the first.

And the KMT also said that asymmetric warfare is quite important, too — and not only the material items, but also the concept itself: we need lengthy and in-depth coordination with our partners, especially the United States, on the real items that we need.

Lin Fei-fan: Ma Ying-jeou was the one who announced the indigenous-submarine project — but he never really put the energy and resources into those defense policies; and actually, it was President Tsai Ing-wen’s administration which actually pushed forward the implementation — including increasing the budget not just for the indigenous submarine, but also our indigenous fighter-jet development. It is also the Tsai administration which formed cooperation with other nations to develop our own indigenous weapons systems.

And not just that. One crucial issue even nowadays — which has become one of the many debates for this presidential election — is people’s attitudes toward military conscription. That’s one key issue which is recognized as a way to show Taiwan’s determination in defending ourselves.

So the KMT is saying that they are focusing on defense, but we don’t actually know their real attitude toward the one-year conscription. Some say that they might roll it back to four months if they get elected; Hou Yu-ih 侯友宜 said that, and now Jaw Shaw-kong 趙少康 reiterated the same stance. But what is the KMT’s real attitude toward it — and what’s the main message the KMT wants to send to the world about their determination in defending ourselves? That’s the question a lot of people are asking.

Lu Yeh-chung: Actually, KMT presidential candidate Hou Yu-ih published an article on September 18 in Foreign Affairs — and in that article, he mentioned the conscription issue. He said that we need to do an overall assessment of the situation across the Taiwan Strait. So it’s not a matter of just cutting conscription back to four months; rather, we need to put Taiwan’s security first. This is quite important.

Secondly, Mayor Hou’s article mentioned one other thing (which was welcomed by many friends not only in the United States, but around the world): if he gets elected, he is going to establish an All-Out Defense Mobilization Council at the executive-branch level, which will be supervised by the vice premier.

This is quite a clear policy argument in this campaign — because for now, under the Tsai administration, all-out mobilization efforts are under the Ministry of National Defense. We need to elevate that to the executive-branch level to make coordination better. So that is the essence of Hou’s idea for defense policy.

The CCP’s Favored Party, and Why

Nicholas Welch: I think it’s indisputable that the CCP absolutely despises Lai Ching-te 賴清德 and Hsiao Bi-khim 蕭美琴 of the DPP. Hsiao Bi-khim, for her part, has been sanctioned twice on the “Taiwan independence” diehard separatists list 台獨頑固分子.

Meanwhile, Hou Yu-ih of the KMT has long rejected the “one country, two systems” 一國兩制 unification proposal; he’s by no means the dream candidate of the CCP either.

So my question here is: why is it the case that the CCP has so much better relations with the KMT, even though, in theory, the DPP would be perfectly willing to accept Communist rule of the mainland? It’s the KMT that wants to unify and install its government in mainland China; KMT vice presidential nominee Jaw Shaw-kong supports unification, but not with the People’s Republic of China.

That’s always been an interesting paradox to me. What do we learn about the CCP from the fact that they treat the DPP with so much hostility, even though if you were just to read the party platforms (KMT; DPP), it’s the KMT, not the DPP, which seeks to be an opposition party to the CCP.

Lu Yeh-chung: Let me explain the VP candidate Jaw Shaw-kong’s position on this. My observation is that people tend to see him as a pro-unification politician in Taiwan. Part of the reason is that he was one of the founders of the New Party 新黨, which used to be a very important political party in Taiwan. The New Party was established in 1993 — and back then, the New Party was quite powerful, especially in the Taipei mayoral election in 1994.

Part of the New Party’s political party platform was in favor of unification. And back then, the majority of people in Taiwan identified themselves as Chinese, or at least Chinese plus Taiwanese.

But also, this was about a power struggle within the KMT: New Party members used to be KMT members — and when the KMT was under Lee Teng-hui 李登輝, these people thought that Lee was leaning toward Taiwan independence. So they used this new political party as leverage, as a political proposition to garner support from the general public. Saying “pro-unification” was one of the strategies they adopted vis-à-vis the KMT.

So for now, I would say that Mr. Jaw seems to be very pragmatic to me. He’s mentioned many, many times that he didn’t go for unification with the CCP because it’s a Communist regime.

But I think no matter what, the decision is going to be made by the Taiwanese people. So Beijing should definitely respect this.

And for now, I would say that Xi Jinping already has a full plate — so I don’t think it is wise to put the Taiwan issue as the first priority to Xi Jinping right now.

So from the KMT’s perspective, maintaining the status quo is the key issue for all candidates in Taiwan. And for the KMT, of course, they have experience interacting with China — so maybe there will be a better chance for the KMT to cool down the situation by having a resumed dialogue across the Taiwan Strait. But, as we have debated, deterrence is still quite important to Taiwan.

Lin Fei-fan: I think that the reason the KMT is more preferable to the CCP is quite clear if you look at the track record and the past experience we have.

The last time the KMT was in power (2008 to 2016), the KMT, based on the foundation they and the CCP both agreed upon — the 1992 Consensus — signed over twenty-two agreements with Beijing. These ranged from social cooperation to economic cooperation, like the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) and the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA). And if the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement wasn’t stopped by the Sunflower Movement of 2014, the KMT probably would have moved forward and pursued more economic cooperation with China.

During those eight years, Taiwan opened the door for Chinese investors and China-Taiwan exchanges. Even today, I think people are still arguing whether and how much space has been left open for Chinese to infiltrate Taiwan society at different levels, from school to religious to community sectors. Without national-security thinking to protect our national interests, that’s quite concerning for a lot of people.

I think from Beijing’s point of view, those eight years definitely were the honeymoon between Taiwan and China. And if the KMT succeeds in this election, it will push forward again and again, seeking more cooperation to integrate Taiwan into the Chinese orbit. That’s why we are worried.

So I think that if you look at the history, you will find that the KMT is preferred by Beijing for these reasons: because they’re more tolerant or more willing to sign agreements, or to accept the terms set by Beijing. That’s the KMT’s performance in those eight years.

As to why Beijing thinks the DPP is not the favorable political party in Taiwan — I think it’s quite clear as well: we choose to strengthen our cooperation with the United States, with our allies in Japan, or other regional countries, and also even countries in Europe.

We are seeking out more like-minded countries, which means democratic partners in the world. That’s our direction. We’re trying to move from the previous track — which was clearly putting Taiwan into Chinese orbit — to a direction that strengthens our cooperation with the democratic allies. I think that’s our choice.

But why have we made this choice? And why we cannot just do some balancing, or play in a neutral way? I think that’s quite clear that the whole strategic environment around Taiwan has been changed, especially by Xi Jinping’s ambition. We’ve seen that after 2012,

Xi is pushing forward the Belt and Road Initiative;

He’s pushing forward the reinterpretation of Hong Kong, trying to absorb Hong Kong and turn it into a normal Chinese city;

We’re seeing the situation in Xinjiang — that Chinese civil society is being cracked down harshly by the CCP; and we see that there’s no civil society space for the Chinese people;

And we see that they’re militarizing the South China Sea — they are invading not just Taiwan’s ADIZ, but also they are invading Japan’s EEZ on an almost-daily basis.

So they are breaking the status quo.

What the DPP administration has been trying to do over the last seven years is to try to secure the status quo. You need to push back those efforts by CCP that try to alter the status quo — I think that’s the basic strategic barrier we face. So we need to have a stronger stance on forming alliances with our democratic partners, rather than focusing purely on cooperating with China, or agreeing to the terms or conditions set by China. I think that’s a basic difference between the KMT and the DPP.

Lu Yeh-chung: I think for KMT strategy — especially how to strike a balance between the cross-Strait policy and foreign policy — it is quite important to know that the KMT is supporting a strategy in which we should make friends with both the globe and China. The KMT is not leaning or hoping that China would put Taiwan into its orbit, much less its pocket.

And also, it’s quite important to know that, under the Ma Ying-jeou administration, there were all those agreements. Those were for functional issues. So this is based on functionalism — what we have learned from the European experiences for economic integration.

These functional-issue agreements actually served as the base to restore certain kinds of political trust across the Taiwan Strait, so that we don’t need to worry too much about potential conflict or skirmish across the Taiwan Strait.

I’m not saying that China is not putting up any military threat to Taiwan. But I think we need to develop a pragmatic way of dealing with it. And even VP Lai once said that he wants to have dinner with Xi Jinping. And if we do not have these kinds of exchanges on functional issues, I don’t think there will be any political base for the two politicians to meet with each other.

One other indication is that, under the Ma Ying-jeou administration, Taiwan got to participate in the World Health Assembly and the International Civil Aviation Organization. That is also a way of demonstrating Taiwan’s sovereign status to the world.

So I personally don’t think that interacting with China and engaging with the world are mutually exclusive.

And adding to that: if this kind of anti-China strategy or logic is accurate all the time, then we wouldn’t see President Biden meeting with President Xi. And we wouldn’t expect to see the Kishida administration from Japan potentially meeting with Xi Jinping in the months to come. So I think this is quite important: we should employ pragmatism — not necessarily ideology — to deal with China.

How Tripwiry is Advocating for Independence?

Nicholas Welch: Here’s a hypothetical: during the 2019 Hong Kong protests, there was a vocal minority — not very many — but there were enough people who felt so strongly about the way the CCP was mistreating them in Hong Kong that they advocated for Hong Kong independence. I don’t think that was a majority position, but it was substantial enough.

Let’s imagine a hypothetical world in which everyone in Hong Kong aired all the shared grievances they had — with the extradition law, with the booksellers, with national security, everything — but nobody said a peep about independence. Do you think Xi Jinping would have used a softer touch with Hong Kong, or would that have made no difference at all?

Lin Fei-fan: I don’t think that Xi Jinping’s attitude toward Hong Kong was based on how many people in Hong Kong were advocating for Hong Kong independence. You actually see that, starting in 2012, Xi wanted to gradually change the status quo.

The CCP’s Hong Kong policy is coordinated with its national-security strategy. If you look at their investments in Southeast Asia — trying to build military bases in the South China Sea, invading the ADIZ — in all those efforts, you see their ambition to alter the status quo.

So they couldn’t leave any space for a place that could be an example of Chinese democracy. If that succeeds, it would have implications for the Chinese mainland.

I think that’s a very simple calculation. They are not basing their actions on Hongkongers’ attitudes toward Beijing, or their relationship with Beijing. They’re cracking down on Hong Kong based on the simple ideology that, if there is one successful example of democracy in Chinese society, that would threaten the legitimacy of CCP’s ruling, and especially Xi Jinping’s ruling.

So I think the logic is, no matter what percentage of Hongkongers advocate for Hong Kong independence, it’s more about how strongly they’re asking for a full implementation of democracy. So they were asking for that in 2014, in 2016’s elections, in 2018, after the extradition bill — the change in Hong Kong wasn’t triggered by Hongkongers’ demands for independence. It was actually the Chinese reaction to their request for implementation of democracy.

The Ultimate Misnomer: the 1992 “Consensus”

Lin Fei-fan: It seems to me that the basic difference between the KMT and DPP is the conditions you’re going to accept in terms of having dialogue with Beijing.

Beijing requires Taiwan to agree that both Taiwan and China are one China — like the 1992 Consensus defined by Beijing in Xi Jinping’s 2019 announcement. It’s quite clear that the 1992 Consensus is a pillar for moving toward unification.

We recognize the importance of having dialogue. We hope that there is a channel for the mutual communication. But if you send a signal to all over the world as President Ma Ying-jeou did from 2008 to 2016 — during that time, we chose to signal to the world that both Taiwan and China are one China. So if you’re asking people to support us in military or security cooperation, you face difficulties since people doubt your credibility.

Both President Tsai and VP Lai have publicly raised again and again the importance of welcoming dialogue between Taiwan and China. But it should be without preconditions. That’s our stance.

For the KMT side, I think their thinking is that, if you strategically agree with some political condition, then you can have dialogue to maintain the so-called cross-Strait dialogues. But on the other hand, you have the sacrifice not just Taiwan’s national stance, but also a stance not in line with the majority of Taiwanese people’s thinking.

Lu Yeh-chung: I think Fei-fan provided a very straightforward explanation of the definition of the 1992 Consensus. Unfortunately, however, his definition is not the real definition of 1992 Consensus. By the KMT’s definition, that one China is the Republic of China. It is Taiwan.

This is the major difference between KMT and also the CCP. Fei-fan’s definition is very interesting, because he borrowed Xi Jinping’s definition.

So I think it is quite important to make sure that, if we need to resume dialogue across the Taiwan Strait, I don’t think under KMT there would be any sacrifice in our sovereignty.

As a scholar, I would say it is quite important to understand and follow the logic of functionalism. Of course, we need to be very cautious about possible consequences. But managing uncertainties is the major task of all leaders around the world.

Nicholas Welch: If I understand both sides correctly:

Basically, the DPP is saying, “If you say ‘one China, different interpretations,’ the whole world is going to understand that to mean the People’s Republic of China. So we’ve made a concession. It doesn’t matter what we believe. It matters what the world believes.”

And then the KMT says, “Listen, we say ‘one China, different interpretations.’ Our interpretation — the Republic of China, not the PRC, is that ‘one China’ — is still super-valid. And so it’s okay to accept that precondition, because then we can do a whole bunch of other functional and important things — like make cross-Strait economic arrangements, and have actual dialogues with CCP leaders.”

Is that about right?

Lu Yeh-chung: Let me add one thing. Even for KMT leaders now, we know that the idea or the term “1992 Consensus” is somehow tainted. So Hou Yu-ih strongly suggested that, even if we have this 1992 Consensus, it definitely needs to be in accordance with the Republic of China’s Constitution. So this is quite important.

And I can go deeper. It seems to me that the KMT right now admits to the reality that there’s a difference between sovereignty and jurisdiction. We are not recognizing each other’s sovereignty — because there is a group of people who thinks that we still represent China — but in terms of jurisdiction, there is no mutual denial on this.

Lin Fei-fan: I want to add one more point about the differences between the KMT and DPP on this issue. It’s not just about Taiwan and China — it’s also about the security of Taiwan Strait.

Here’s another major difference: if I heard what Dr. Lu said, if you’re agreeing with “one China,” then Taiwan’s issue with China is simply a matter of Chinese internal affairs. But it seems like that if you are agreeing with “one China,” that would send a signal to the world that the issues related to Taiwan and China should just simply be solved by the Chinese on both sides.

From our point of view, we believe that the issues of the Taiwan Strait should be an international affair. It’s not just purely between Taiwan and China; it shouldn’t be a Chinese internal affair.

Lu Yeh-chung: I think for all KMT politicians, none of them — at least that I have heard — has ever suggested that cross-Strait relations is an internal affair. So it is quite important to note that, again, Fei-fan did a good job by pointing out that the DPP’s position is so straightforward. But we all know that, in reality, nothing would be that simple or straightforward.

We need to interact across the Taiwan Strait with our counterparts to understand what they are thinking about the future of the Cross-Strait relations, the relations with the rest of the world — those are the key tasks for the KMT, if the KMT is to win the upcoming presidential election.

But also, in the meantime, the KMT doesn’t say that it isn’t important to coalesce with our friends around the world. Actually, the KMT also suggested that we should cooperate and collaborate with like-minded countries, like-minded democracies around the world — not only for security, but also for Taiwan’s economic prosperity.

So to me, I wouldn’t say there’s a huge difference between the KMT and DPP regarding Taiwan’s security. But how to achieve that goal — that’s the difference between the two major parties.

Lin Fei-fan: Dr. Lu said that no one in the KMT says the issue of the Taiwan Strait is a matter of Chinese internal affairs. But actually, KMT International Department Director Alexander Huang Chieh-cheng 黃介正 said in June 2022 that the Taiwan Strait is actually in the waters of the Chinese Sea. So he made that point, and he faced a lot of criticism on this.

Lu Yeh-chung: I mean, I don’t know how to deal with that. No one says it’s Chinese internal affairs. So that’s it.

Taiwan Politics Sans China

Nicholas Welch: If the China issue were to be magically resolved, what would be left of your parties’ platforms? What are the key differences between your parties?

Lin Fei-fan: I would say that DPP leans more toward social-welfare policies. I would say it’s a center-left or more liberal political party. Compared to the KMT, we’re more willing to accept more progressive ideas. For example, we achieved LGBTQ rights during our terms in the government; we have subsidies for young parents; we are putting more vouchers on health care for the elderly; and we are putting more energy into some infrastructure bills to push forward infrastructure developments.

Lu Yeh-chung: I think on social issues, those are also the concerns of the KMT. And adding to that, I would say economic development is very important, because we witnessed that our economic growth rate was actually dwarfed by the neighboring countries in the Indo-Pacific region.

The other issue is about Taiwan’s energy. We know that we need to achieve net-zero. The energy issue and economic development are two sides of the same coin. So managing those kinds of risks and uncertainties is quite important.

And also education — that is quite important to Taiwan. Because we know that the birth rate has actually been quite low in the past few years in Taiwan. So it’s quite important to make sure that everybody can have quality education, so that we can have a quality labor force in the years to come.