The CCP's Eternal "Politics of Simpletons" + Tweets of The Week on Kung Fu Panda, Mongols, and Carbs

“If we don’t hold meetings, how do we show that we’ve implemented our work?”

Two announcements at the top. First, this month I’m launching the ChinaTalk-Rhodium Student Research Symposium! If you’re graduating this semester from an undergrad or masters program, and have done any research incorporating Chinese-language sources, submit your paper or thesis for consideration here! Authors of the best five papers will win $200 each and have the opportunity to appear on the ChinaTalk podcast talking with me about your findings. Profs, please forward to your students!

And second, I’m hiring! Rhodium is looking for a research assistant to support our growing technology and industry research practice. If you have confident Chinese and strong English-language writing skills, a passion for technology policy and industry analysis, and maybe some Python or R, please apply here.

The following was written and translated by Alexander Boyd, a freelance writer. His Twitter handle is @alexludoboyd.

In Xi’s China, cadres find themselves in a trap. As one county chief recently put it to Xinhua: “If we don’t hold meetings, how do we show that we’ve implemented our work?”

And so a vicious cycle is born. Meetings cannibalize work time, leaving cadres grasping for proof of their achievements, leading to—you guessed it—more meetings. This pathology, “formalism” in Party parlance, is endemic to the Chinese Party-state but likely grows more acute during times of tightening in thefang-shou cycle.

An essay published in the back pages of People’s Daily in May of 1957 put the “cadre’s conundrum” plainly. “Discard the Politics of Simpletons,” written under the pseudonymous byline Bu Wuji (translation: foretell no superstitions), singled out the endless seas of meetings, discussions, and paperwork that resulted from politics in command for criticism. Cadres’ pie-in-the sky plans, lust for glory, and penchant for choosing the superficial over the practical also received withering scrutiny.

The essay was a subtle critique of the Hundred Flowers Campaign and agricultural collectivization. After Khrushchev’s address to the 20th Congress of the CPSU in 1956, “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences,” sprung de-Stalinization on the global Communist movement, Mao—shaken by the perceived attack on his own Stalinesque personality cult and naïvely confident in the Chinese public’s ardor for the Party—launched the Hundred Flowers Campaign, inviting criticism of life during the first seven years of the People’s Republic. The campaign was soon abandoned in favor of a nationwide purge after an unexpectedly boisterous outpouring of complaints.

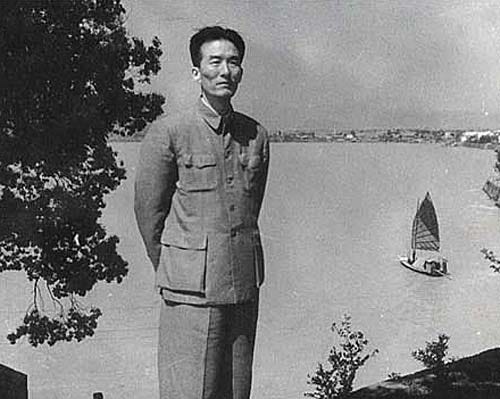

The identity of the essay writer remained a mystery until the Cultural Revolution. It wasn’t penned by a would-be dissident unhappy with his lot in the new regime but by a Maoist of the highest order, Deng Tuo, then editor-in-chief of People’s Daily. Deng was a Leninist literatus; both profoundly dedicated to the CCP and an independent thinker with a passion for China’s cultural heritage. His life and work are given great detail in Timothy Cheek’sPropaganda and Culture in Mao's China: Deng Tuo and the Intelligentsia. He was primarily famed for his columns, Evening Chats at Yanshan and Notes from a Three Family Village, as well as a Marxist history of famine relief in China published in 1937. “Discard the Politics of Simpletons,” sprinkled with classical verse, is a testament to his idiosyncratic mind.

For those observing China today, Deng’s words remain salient, especially when it comes to rural work. As Scott Rozelle put it in ChinaTalk recently, “It's a lot easier to solve poverty for 20 million people than it is to solve the low-income problem for 900 million people.” But history is only a rough sketch of the present and the Party has changed with the times. Deng’s writing should be read primarily as a window into the Mao-era, no matter how tempting the present parallels.

“Discard the Politics of Simpletons” by Bu Wuji (邓拓, Deng Tuo)

While observing recent events, I awakened to a truth. Precisely as the Tang Dynasty’s Lu Xiangxian put it, “There are basically no problems under heaven, simpletons stir them up themselves.” Some comrades among us rush about, I don’t know why, day-in and day-out to do completely unnecessary things. No matter the issue, they cannot bear to let things go. All must be seized, and seized with a death grip no less.

For example, a comrade in County X sends out an order calling for all the county’s cotton to be topped at the same time [the process of topping cotton in Mao-era China is shown in the opening song of this 1958 film]. Accordingly, rural and commune cadres frantically put their members and organizations to work. In a number of fields where the cotton is not yet ready for topping, they top the shoots anyways.

Similar examples abound. When inspecting our previous work, was not a great deal of it unnecessary! Speaking strictly of personnel work, a large portion of it is unnecessary.

We’ve created a system of bureaucratism for ourselves. After deploying cohort after cohort of cadres, we then deploy a separate group of people to do personnel work. One must discuss with them often, hold meetings, help them write reports, read reports, approve reports, etcetera etcetera. We’re busy to no end, and the majority of cadres become trapped in daily “public work” from which they are unable to extricate themselves. We comfort ourselves, and everyone else, by saying that we serve the people and that it is all indispensable “political” work.

I think that if we must call all of this “politics” then we can only say it is a politics of simpletons. Approximately speaking, any political activities that rely on optimistic wishes, pursue superficial results, crave glory, and lack actual outcomes can in practice be called “a politics of simpletons.” Apart from allowing those truly good-for-nothing simpletons to revel in their own mediocrity, what is the use of such a politics?

Right now, some comrades clamor emptily to strengthen ideological and political work. They show themselves to be busier by the day, busy holding meetings, discussing, reporting, and the like. At times they’re too busy to breathe. These comrades have no real understanding of ideological and political work nor the masses’ most urgent demands.

These comrades should calm down. First they must think of a way to completely rid themselves of the politics of simpletons in order to change themselves into true political workers.

But to be a true political worker is not easy in the slightest. Many turn to the politics of simpletons without realizing it. We see before us fools, some who even have the power to command. In this way, it is inevitable that the politics of simpletons would arise in some areas. If they take the next step towards developing this politics of simpletons, it will develop as mediocre doctors treating illness does, everything goes to pieces.

In a poem, Lu Fangweng [Lu You] wrote: “An incompetent doctor commands a life, an idiot critiques an essay.” This is a cutting warning. Think about it: if a sick patient meets an incompetent doctor who randomly prescribes medicines and treatments, a trifling flu will grow more serious, and finally become fatal. Is this life not trapped in the hands of an incompetent doctor? If a great essay falls into the hands of an idiot, they will believe they understood the whole thing, nitpick, and wantonly add in “corrections.” Isn’t this a shame? When an incompetent doctor takes responsibility for your treament, your life is in their hands; when an idiot serves as your editor, your essay will assuredly be critiqued and excerpted at random.

I myself have been both a patient and an editor, so I’ve got a feel for both sides. These few words were spoken from the heart and were not an alarmist’s cries. I hope that my comrades will think and reflect deeply on this issue, and, please, at all costs avoid drafting chaotic plans like incompetent doctors randomly prescribing medicines, killing the patient in hopes of avoiding harm. In regards to problems that you don’t completely understand, it’s best to avoid taking the initiative.

There are still those who will unhappily retort: Is this not abandoning leadership, letting the chips fall where they may? Answer: It both is and isn’t. It is because our leaders must boldly relax their grip, relax it again, and relax it once more; I fear that the leadership styles of the past must be reformed, which is to say, there should be a certain degree of relaxation. It isn’t because in principle and in practice there are still leaders. We must never transform into a state of anarchy. As the masses of people have undergone revolutionary education, I believe they will never stumble down that path. With that being the case, there is really nothing to fear. Those who fear chaos and yell constantly that “we can’t ease our grip” are simpletons troubling themselves in search of wrong, worrying about nothing.

Deng’s life ended in tragedy. His connections to Peng Zhen, mayor of Beijing at the start of the Cultural Revolution, led to his downfall. Peng was the mayor when Wu Han, a historian unfortunate enough to have answered Mao’s call to write plays about Hai Rui—an upright Ming dynasty official—was purged. Deng was called a traitor in the pages of the paper he formerly edited. Children sang nursery rhymes about his demise: “Wu Han, Deng Tuo, Liao Mosha; three black melons from the same vine. Strike! Strike! Strike! We’re determined to strike them down!” Deng committed suicide on May 17, 1966, making him one of the Cultural Revolution’s first victims. The final line of a parting note he left to Peng Zhen and others read: “This heart of mine has ever been respectfully loving of the Party, respectfully loving of Chairman Mao.”

Deng was posthumously rehabilitated in 1979. By 2012, his world-class collection of Chinese art was on exhibit in the National Art Museum of China. In 2016, Qi Benyu, the infamous Central Cultural Revolution Group polemicist who had labeled Deng a traitor in People’s Daily, wrote in his memoir that he regretted forcing Deng to commit suicide.

Tweets of The Week

Uniqlo isn’t anywhere near Muji-levels of indifference to Xinjiang. The government wanted records of the entire processing history of the cotton. Expect more firms to get caught in this dragnet.

Quoting from Chenchen’s thread: “you’ll be able to visit the White House. They (grade 9 students) took a bus for hours to Chengdu, then a 40 hour train ride to Beijing on a “hard seat” ticket…to visit the website of the WH. He remembers the excitement and that the teacher was telling them this was the magic of the Internet. “You kids from the mountains in northeast Sichuan can know what’s happening across the Pacific Ocean directly from the US presidential office”, and the image of the US as a “civilizational beacon”…he thinks its events like this that seeded the dream of going to the US in the hearts of so many students.”

And if you think manufacturing mRNA vaccines are hard, just try a 5nm chip on for size…