After decades of neoliberalism, how much can America’s bureaucrats crank the dial on effective industrial policy? Will the CHIPS Act succeed at reshoring high-tech manufacturing?

Next week is the CHIPS Act’s second anniversary. To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed Ben Schwartz, the former director for national security at the CHIPS Program Office, which manages a $39 billion grant program appropriated by the CHIPS and Science Act.

Have a listen in your favorite podcast app! Here is the link for Apple Podcasts, and spotify is below.

We get into:

The methods and obstacles for American semiconductor policy;

How CHIPS Act guardrails aim to balance economic growth and national security;

The negotiation process for companies interested in receiving CHIPS Act funding;

Reshoring vs friend-shoring and the challenge of Chinese dominance in legacy chip manufacturing;

Staffing and organizational structure of the CHIPS Program Office, plus the role of Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo;

The challenge of collecting data on secretive semiconductor supply chains.

How to Spend Billions — Grants vs Tax Breaks

Jordan Schneider: To start, why does the CHIPS Program Office matter?

Ben Schwartz: This is the most ambitious industrial policy launched by the US government in more than a generation. What I mean by “industrial policy” is government action to shape the supply chains and market for a major industry — semiconductors, in this case.

This is a huge change. It’s not just that the US is not a centrally-planned communist country — it’s that the US is also not like France. It’s not like Singapore. We don’t have a long history of the central government awarding billions of dollars in grants to shift the economy.

To be candid, it’s anathema to traditional American cultural and political proclivities. A large government-administered grant program is just not the first choice because when you do something like this, you have officials picking winners and losers — and the losers always claim that they were treated unfairly.

Americans just are not really comfortable in having the government get involved with large, profitable companies.

Yet in this instance, the alternative to a grant program would have been the economic equivalent of unilateral disarmament.

That is not an exaggeration. I use a military analogy here because we are in a fierce competition to shape semiconductor supply chains.

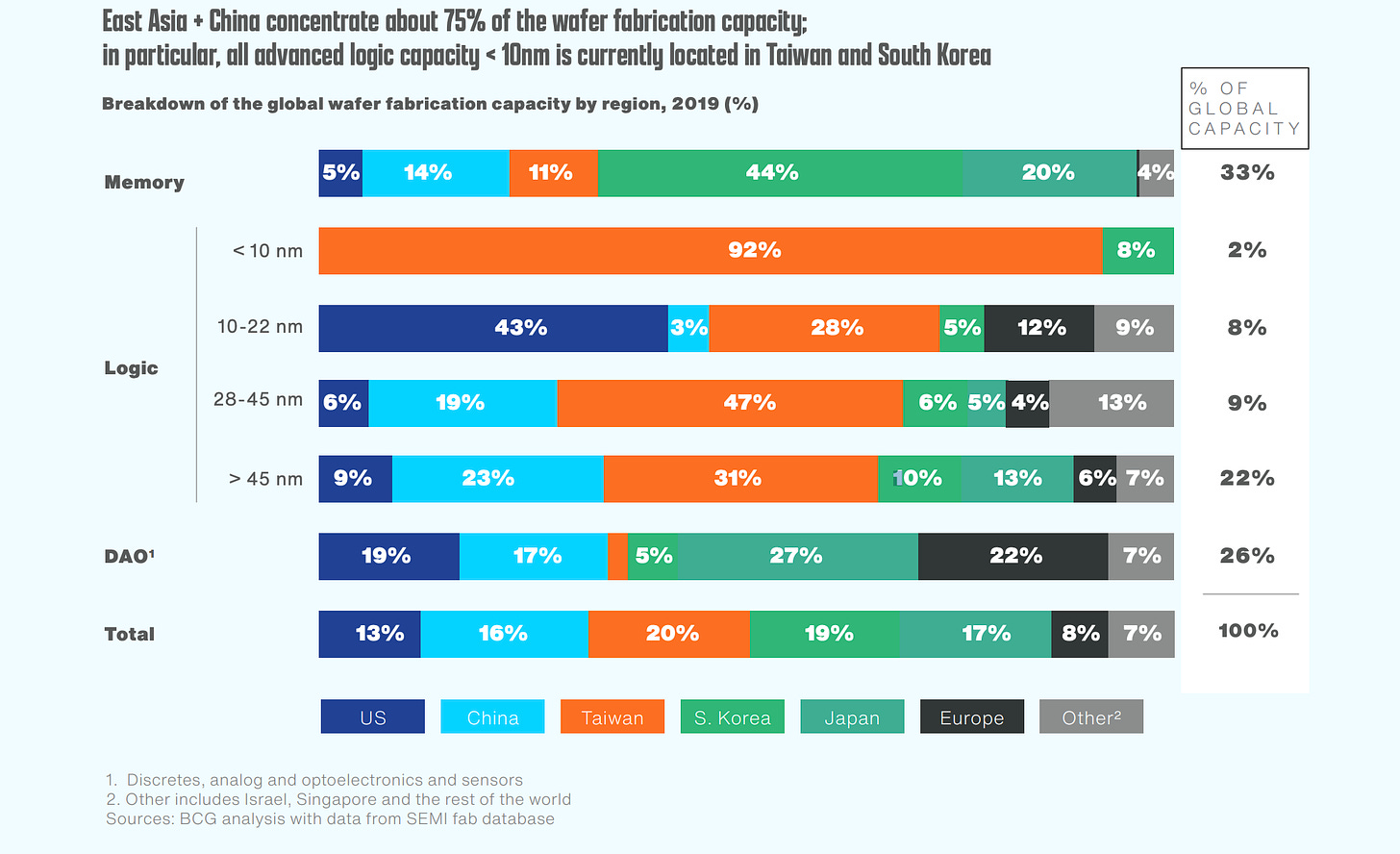

For decades, the US government sat back and let foreign governments shape those global supply chains. The US used to be the leader in semiconductor manufacturing in the sixties, some call that our golden age. We did basically everything, but over time we lost leadership, and we went from 40% to 12% of global manufacturing.

We ended up in a situation where we were producing exactly zero leading-edge chips.

That’s a problem that transcends the individual market participants. That’s a public problem, a collective action problem, a national security problem. It’s not just that we lost the leading edge either — we also experienced shortages in legacy chips (also called foundational chips).

During the COVID pandemic, there were acute shortages affecting the auto industry, with huge impacts on our economy. By some estimates, the Chinese government has been adding around 80% of new capacity in legacy chips for the past couple of years.

We face a situation where the absence of US government action here isn’t a free-market, neutral situation. No — foreign governments have acted with their own incentives. Companies acted on a very understandable profit incentive to increase margins and lower costs — but that has resulted in extreme geographic concentration risk in terms of where this stuff was being produced. 92% of all leading-edge chips are produced in Taiwan.

This is a real issue, because if you lose access to those chips, it’s not just going to affect a couple of consumers, it’s going to affect the entire economy. If we lost access to those leading-edge manufacturing capabilities, it could affect 10% of the global economy by some estimates.

This is a major effort to shape supply chains in a way that increases our resilience and helps alleviate a really acute national security risk.

Jordan Schneider: I’m completely convinced that the status quo was not sustainable from an economic and national security perspective. But about the methods we chose for dealing with this problem.

There already was a big tax and investment incentive baked into the CHIPS and Science Act. If we’d stopped there, we wouldn’t have to bother with signing individual agreements, not to mention the heap of riders making demands on companies.

Why did the CHIPS Program Office choose these specific methods?

Ben Schwartz: $39 billion may sound like a lot of money, but in the semiconductor industry, it could cost as much as $30 billion to build just one fab. You really need to be nuanced and creative in how you stretch that funding. We needed to basically negotiate and push companies in directions that they wouldn’t consider for a flat amount of funds.

The fact that there was candid uncertainty about timelines and how much money companies would get, actually crowded in more private investment than a single straight tax deduction.

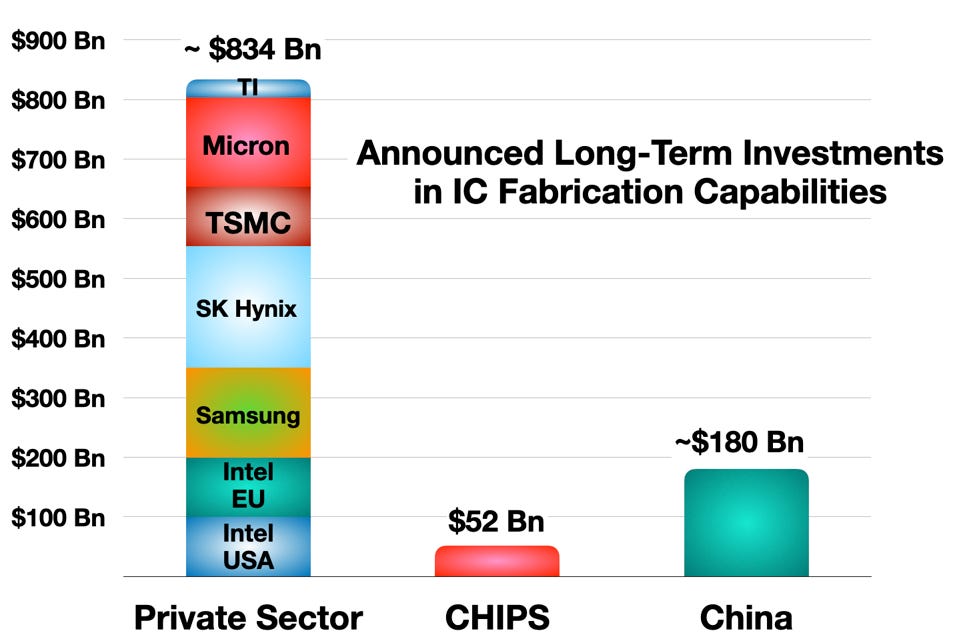

The process of negotiating crowded in a substantial amount of additional funding. The Semiconductor Industry Association came out with a figure, in which they stated that they estimate that something like $264 billion had been crowded in since it was signaled that the CHIPS and Science Act would pass with this grant program. The White House website had a more ambitious figure – something like $640 billion in new investments associated with chips. The reality is somewhere in between those two numbers.

[Jordan after the fact: I wouldn’t necessarily put an industry association who has every incentive to show the bill is a success as a lower bound here, but clearly the number is in the hundreds of billions]

It’s also really important what that money represents. Tangibly, the kind of investments we’ve gotten in the United States are themselves quite significant. The $100 billion multi-state program that Intel is committed to is unlike anything we’ve seen in American history. The $65 billion commitment that TSMC has made, the leading semiconductor company in the world, is the largest foreign investment we’ve ever seen. Samsung comes in shortly under that with $40 billion, the second leading-edge foreign company in the world. We have seen Micron’s investment of $75 billion for leading-edge memory. SK Hynix also announced their own investments in the United States.

The fact that those companies are committing to what they’re committing to doing here in the United States is also an unquestionable success of this program. That’s unambiguous. There is no other country in the world that has the combination of that kind of technology and those companies all operating in the same space. It’s not clear to me that you would have gotten that kind of thing just from tax incentives.

Companies are going to do whatever maximizes their profitability. That’s their responsibility to their shareholders, which inherently means that longer-term resiliency questions about supply chains are not going to be prioritized.

If you give a tax incentive — that will cut costs for a shortened period of time, but if there aren’t hooks in that funding stream, then over time those companies are just going to default back to maximizing efficiencies rather than maximizing resiliency.

In this instance, the reason this is a national security problem is not because costs are too high. That’s not the problem. The problem is that there’s this severe geographic concentration risk and that doesn’t get solved with the flat tax. You actually need hooks into these agreements that keep companies focused on where this stuff is manufactured and what their supply chain looks like from a resiliency standpoint.

Jordan Schneider: Regarding supply chain resilience — CEOs read the news too. Would any of these investments happen without the CHIPS Act, or did it feel like you were pushing on an open door?

Ben Schwartz: There’s a spectrum of sensitivity among companies in this space. Companies, particularly those that are feeding the auto industry directly, probably have been more sensitive to the need for resilient supply chains, mostly because the auto industry experienced very painful shortages and have told some of their suppliers to diversify their footprint.

There are other parts of the supply chains that have not. It was shocking to hear how much they simply didn’t care that they were exposed to risk in certain parts of the world.

There would have been some investments in the United States, regardless of the CHIPS program. Would it be anything like the degree that we’ve seen? Absolutely not. This unquestionably had a significant impact in shaping where these projects were to be built.

I have a humble view about the role of the US government in shaping private industry. We need to be aware of the limits of what we know and understand about very complicated supply chains. We have to be humble about the tools that we have available to actually shape those things, which are not nearly as powerful as some people in Washington assume they are. We had really a significant impact here, and we’ll continue to have it as long as this program exists.

If you’re a CEO, you’re focused maybe on the next five years, maybe ten years — your time horizon is just inherently shorter than what’s really in the public interest. This is something that is actually a fundamental issue in terms of the competition we face with the Chinese Communist Party. There is somebody in Beijing that has been focused on industrial policy for decades, and that person has time and the ability to really drill down on a subject and plan things that will impact the Chinese economy for a long period of time that doesn’t like that.

Issues of time and focus are not areas where the US political system has an advantage. We don’t do that well. But industrial policy really does require that focus and the ability to think in longer terms, which is why, candidly, industrial policy in the United States is only going to work if it’s bipartisan. The CHIPS and Science act was a bipartisan thing. My hope and prayer, candidly is it remains that because it’s the only way that it’s going to work over time.

Jordan Schneider: In thinking about Taiwan contingencies, is an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure? Is there a possibility to fix this in 15 or 20 years?

Ben Schwartz: There’s no risk elimination in this scenario. This is about risk mitigation in terms of where we try to diversify the geographic footprint of critical manufacturing. I will say that the way that I think about this is that it’s much harder to go from zero to one than go from one to two or one to three in terms of just capacity. Just having a foundation of, say, leading-edge capability here in the United States, even if it’s relatively small in terms of global capacity, is still extremely valuable from a resiliency standpoint.

I also think that there’s a technology leadership factor as well, which is just having advanced technology in the United States can create a virtuous cycle in terms of having people that need to be trained in the United States to operate those fabs to have a research and development function.

I’m very proud that in some of these deals we’ve negotiated, it’s multifaceted. It creates these positive clusters that involve not just manufacturing, but leading edge R&D and supply chain clusters and things like that. You get this virtuous cycle of innovation and growth and whatnot. There’s places for people to go work after they study and et cetera, et cetera. There’s the resiliency question and factor about having capacity here, but there’s also the technology leadership aspect of having advanced capabilities in the United States.

Negotiating Semiconductor Security

Jordan Schneider: We’ve talked a little bit about why leading-edge logic capability in the US is something that’s important and relevant over the long term. But more broadly, how did you guys conceptualize what national security meant in the context of the CHIPS Act’s mandate?

Ben Schwartz: This is a subject that doesn’t get nearly as much attention as some other topics. But obviously, it’s important because it was the NATSEC team, it was my team that was leading a lot of these efforts. Let me break it down into a couple of components.

We use the Presidential Policy Directive 21 to help identify what we mean by “supply chains critical to national security.” These are things like aerospace and defense industries, transportation, the electrical grid — things that affect the public writ large and don’t just decrease the cost of a personal electronic device for an individual consumer.

This is an area that is of greatest interest to the public. When we looked at project proposals, the first thing we asked is, “If we increase capacity here in the United States for this, how is that going to feed these critical supply chains, or will it at all? Will it feed the defense industrial base?”

One of the things that’s absolutely essential for our society to function is not just a free economy and a functioning economy, but military capabilities to protect that economy. Today, that means that we need to make sure that the supply chains behind the F-35, the F-15, and other major weapons systems are not vulnerable to disruption.

I’m especially proud that our team was able to convince some of these applicants to onshore critical defense capabilities. In some instances, they introduced technologies that had just never been available to the DIB, because sometimes you actually can’t incorporate technologies manufactured abroad for security reasons into majority sensitive programs. Now we’re going to have those here in the United States.

Next, we needed to make sure that these investments were reasonably protected from various types of threats. The statute that authorized our program specifically called out things associated with “operational security” — cybersecurity, the threats of counterfeits, concern about foreign influence and control of operations, et cetera.

I was very privileged to work with a team of just absolute superstars with the nerdiest but most critical knowledge of things like cybersecurity standards and how equipment communicates with the internet and outside systems. How do you structure corporate governance to make sure sensitite information doesn’t leak out to foreign countries?

Finally, at the direction of Congress explicitly, the team focused on implementation of guardrails. In Congress’s infinite wisdom, they put in some fairly pointed language about preventing the expansion of capabilities in foreign entities, of concern foreign countries, of concern for companies that receive CHIPS grants. The point is that we don’t want to inadvertently advantage the development of technologies related to national security in a country like China or Iran.

There’s actually a lot of nuance in implementation. It’s actually quite complicated interpreting that statute, applying it consistently, and doing it in a way that maximizes national security but also allows companies to remain commercially competitive and viable.

These things, the resiliency question, the operational security question, and the guardrails implementation are things that don’t get a lot of press. But over time, as people study this program, people will, more people understand, actually the critical importance of this work.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss bringing manufacturing here. Anything can be susceptible to cyberattacks. We just had half of the American economy go offline because Crowdstrike had an incompetent intern.

It’s one thing to have manufacturing here, but these fabs need data flowing in and out. Is it even feasible to secure them?

Ben Schwartz: Yes. There’s a way to structure and manage this problem. I was privileged to serve with cybersecurity professionals. The traditional way of managing this kind of issue is through the formula Risk = Threat × Vulnerability × Consequence. This is typically used in the security community to break down seemingly unmanageable operational security risks into components and address each component reasonably.

Standards exist for cybersecurity, but there’s also the operational structure. You visit these facilities and check their physical security program, insider threat program, contractor vetting processes, and information firewalls to prevent leaks to foreign parents.

We can’t eliminate risk entirely, but we can minimize it, focusing on the most consequential aspects from a national security perspective.

Jordan Schneider: Was this a culture shock for organizations unfamiliar with the Pentagon’s extended universe? Had these companies been thinking about these issues? You mentioned earlier that there was a lot of teaching on your end.

Ben Schwartz: It varies. Some companies have been serving the defense industrial base for a long time and have robust protections in place. They might be part of the Trusted Foundry program, administered by the Department of Defense to ensure classified and sensitive systems are supplied with parts and semiconductors that go through rigorous security structures.

Other companies have never served the defense industrial base and weren’t interested until we pushed them because we had leverage. Some of the most advanced technology comes from companies that get their margins purely in the commercial space. When they look at the margins for working with the defense community, they wonder why they should bother. In our case, we said they should because this is a national security program, and they need to provide a good justification for receiving funding.

There are also companies that will probably never work with the defense industrial base, but were interested in increased security because they were aware of vulnerabilities in their commercial operations. Smaller companies, as well as those that had gone through mergers and acquisitions, didn’t have uniform standards in place. They welcomed the opportunity to learn from and partner with the U.S. government.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about the CHIPS guardrails. What were some of the decision points you had in implementing that provision?

Ben Schwartz: I can’t discuss particulars for individual companies. Legislation is never perfect in terms of its ability to be translated into clear programmatic decisions. Congress used categories of semiconductor technologies of national security importance throughout this legislation. We’ve had to figure out how to use those categories to align with the increased complexity of how things actually work in the real world.

Our objective on the national security side is not to kill projects in the United States through non-commercial security standards, because that doesn’t serve national security. The least secure project, as I told my team, is the one that doesn’t exist.

Jordan Schneider: For context, the CHIPS guardrails essentially state that if you’re going to take CHIPS money, then there’s a time horizon during which the U.S. government has a say in whether or not you invest directly into the PRC. If you decide to build a plant or expand your footprint within China during that period, the CHIPS Program Office can reclaim its money. This was very relevant to many companies because they have fabs, manufacturing facilities, or long supply chains running through China.

Ben Schwartz: To clarify, there’s the expansion clawback that deals with expanding capacity in foreign entities of concern, and the joint technology and licensing clawback that addresses the nature of partnerships with foreign entities of concern. We had to manage both of these requirements in the program.

Jordan Schneider: There’s been news about Intel Capital and other direct investments into startups. Is that your problem, or is it the outbound investment screening team’s issue?

Ben Schwartz: I can’t comment on anything related to a particular company that hasn’t been made public.

Jordan Schneider: Over the course of this process, do you have a favorite deal that exemplifies why the CHIPS Program Office should exist?

Ben Schwartz: Every deal is unique, which makes this program special. We were able to attempt to get the maximum bang for our buck with each applicant by negotiating in a highly particular way to extract the most economic and national security value from these deals.

I particularly liked one of the first deals we announced, with BAE (British Aerospace). It’s a small deal, about $35 million for preliminary terms, but it’s a smart use of U.S. government funding. BAE produces monolithic microwave integrated circuits (MMICs), which are essential to electronic warfare systems in aircraft like the F-35 and F-15. There had been a significant backlog, and they couldn’t produce enough, which held up key components of major defense programs.

By using CHIPS funds to support the expansion of capacity at this BAE facility, we were able to address the backlogs for MMICs and lower the overall production costs due to greater economies of scale.

This eliminated backlogs, created more resilience in a critical supply chain, and reduced costs that would ultimately be borne by taxpayers.

The facility is also a trusted foundry, increasing capacity at a site uniquely suited to creating trusted microelectronics. [Ed: CHIPS incentives quadrupled mature-node production at the BAE facility in New Hampshire.]

Supply Chain Data Sleuthing

Jordan Schneider: Semiconductor supply chains are fed by a long tail of components, which is impossible for one person to fully comprehend.

The type of negotiations conducted by the CHIPS Program Office help the government gather information and get closer to situational awareness.

What was the process like for the team to synthesize all this new data?

Ben Schwartz: It’s not an exaggeration to say that the wealth of information we compiled about certain parts of the microelectronics industry is better than any other collection on the planet.

The government is the only entity that can really solve the collective action problem of dealing with geopolitical risks from high concentration of supply chains. We tried to get the best deal by looking at the finances of these companies to determine what we needed to do to get them to build here sustainably, and not a penny more.

Jordan Schneider: There’s no way that these companies would discuss commercial secrets with any centralized data broker other than the U.S. government.

Ben Schwartz: Having worked in private industry as well, I’m aware of the limits of what these companies will ultimately share with us. We did the best that was possible, and that dialogue will continue over time.

It benefits these companies to think about supply chain resiliency issues.

There are multiplier effects where they identify vulnerabilities such as overreliance on a single supplier, and express a desire for more options or a preference for a specific geographic location.

The U.S. government can then consider that when allocating resources.

Jordan Schneider: Can you talk about the Defense Production Act survey and how that potentially fed into some of the BIS export control efforts?

Ben Schwartz: The CHIPS Program Office isn’t part of BIS, but we all work together. Secretary Raimondo was direct when that survey was released — industrial policy is a multivariable equation. If you want increased resiliency, multiple factors affect that output. Grants are just one tool — others deal with trade restrictions, or protect against the non-market behavior of other countries.

We need to understand where these chips are coming from and what foreign governments may be doing. The survey is a tool for the U.S. government to understand supply chains that affect national security. Depending on what information is received and what we learn about foreign governments, other tools in the U.S. government toolbox will be seriously considered to manage risks.

The Chinese have a playbook for flooding markets, which makes the competition the U.S. faces today distinct from the Cold War era.

The Soviet Union never had the same level of integration in the global economy where its exports could drive foreign companies out of business. The Chinese government has that ability if they decide they want to control certain technologies. They can fund something for a very long period, drive prices down to a level where foreign companies can’t compete, and drive those companies out of the market. We need to ensure that doesn’t happen.

Jordan Schneider: Legacy chips are particularly tricky. We’re currently running an essay contest with Noah Smith and Chris Miller about how the U.S. government could address the impending onslaught of Chinese legacy chips. It’s a similar problem to what happened with solar panels.

It’s challenging because you’ve already spent a lot of the money, but it seems like you’ll need to use many different tools to address it. Do you have any particularly clever ideas or suggestions for tools that would be especially relevant in this case?

Ben Schwartz: This isn’t a new statement, but one thing that must be done is to improve traceability and visibility in supply chains. We can’t take effective action until we have a more granular understanding of where chips are produced and how they’re integrated into manufacturing here.

We don’t want to unintentionally make manufacturing uncompetitive in the United States by cutting out the supply of chips that feed that manufacturing.

We also need to have a dialogue with companies about how to effectively protect these markets from non-market behavior. Companies have been hesitant, partly because they may not have the information themselves. It takes money and time to understand where you’re getting your chips from.

We need to have a conversation about the outcomes we’re trying to achieve and how to get there. There’s an information gap, and if the U.S. government takes action, it tends to be a blunt instrument. These are highly complicated markets, and a blunt-force approach could be counterproductive to our own ends.

In terms of tools, we can use are 301 investigations, 232 tools, and Section 5949. These all relate to trade controls – restricting the import of goods that are being produced for political reasons.

The distinction is important: the U.S. is a market economy, but some governments use market dynamics for political ends. Their goal isn’t to create self-sustaining industries, but to control technologies for leverage in political and military contingencies. That’s where trade barriers come in, and where we have to protect the country from that kind of threat.

Keys for Leadership and Bipartisanship

Jordan Schneider: Is there any Monday morning quarterbacking you want to do here? Any soapboxes you’d like to stand on?

Ben Schwartz: No program is run perfectly, but I’ve never been as impressed with the public servants I’ve worked with as I have been in this program. A professor of mine compared it to the Manhattan Project in terms of pulling talent from the private sector and other parts of the government together to do something critical for the country in a short period of time.

The most important lesson is that there are limits to what you can accomplish in a short time when trying to do something of this magnitude. You really need bipartisan support to allow the longevity necessary to achieve the desired successes. If a program like CHIPS were to get politicized – which happens easily in this town – it would hurt the country’s ability to compete with China and others.

The lesson is that if we’re going to undertake things of this magnitude, which I believe we absolutely must, it has to be a strongly bipartisan program and must be viewed as a longer-term initiative. The second lesson is that grants are just one tool in the toolbox, and you have to integrate that tool with others that the U.S. government has available, such as trade barriers and countervailing duties.

The U.S. government isn’t really organized to do industrial policy the way we’re organized to do monetary policy. The Fed was designed as an institution to handle monetary policy, and it’s done well over time because it’s typically been non-political and bipartisan. We haven’t institutionalized things for industrial policy like the CHIPS Act in that way, and that may be something that’s really required.

Jordan Schneider: You had one tricky news cycle with the daycare issue, but it’s remarkable how much this has stayed out of the political maelstrom. Whether that means we’ll get more billion-dollar industrial policy pushes in the future remains to be seen. But it’s a testament to the work you did to convince people that this is a special initiative that shouldn’t necessarily be leveraged to pursue other domestic policy goals.

On the Manhattan Project talent concentration perspective, you’ve mentioned many other organizations you’ve worked with. Were people excited about it? I know you had special hiring authorities. What were the ingredients to get the right team in place?

Ben Schwartz: You’ve already named one of them. This stuff is fundamentally about people at the end of the day. We were able to benefit from Secretary Raimondo’s leadership, which I haven’t seen anywhere else in my time in DC.

I’ve supported over half a dozen cabinet secretaries in different jobs, and her direct leadership in getting this up and running, combined with the fact that she’s a cabinet secretary working for a president who made this a priority, was crucial.

Jordan Schneider: Can you elaborate on why cabinet secretaries matter?

Ben Schwartz: When they say to get something done, there’s a system in place to compel people to act. When you’re a mid-level bureaucrat in the system, it’s much harder to make things happen. Most programs in the U.S. government are run by mid-level officials because the authorities and responsibilities of a cabinet secretary are vast. Their attention and focus get diffused among many things.

The direct hiring authority was also essential. We didn’t have to go through some of the typical processes that often dilute the quality of people coming into these jobs. The bipartisan aspect was also instrumental in this whole endeavor. There’s nowhere else that I’ve seen that in my experience in government.

Jordan Schneider: Can you give an example of a roadblock that the Secretary could clear that you, as a lower-ranking official, wouldn’t be able to?

Ben Schwartz: The ability to engage with company leadership, the White House, and other agencies is crucial. CHIPS had dependencies outside of the Commerce Department, meaning other agencies needed to act or refrain from acting for us to be successful. In government, you never want dependencies in other agencies because it’s like a tribal confederacy. They have their own imperatives and won’t necessarily do what you want just because you’re part of the same government.

But when you have senior leadership, they can call another cabinet official and say, “Please resolve this by the end of the week,” and things get done. I imagine it’s not that dissimilar from certain companies in the private sector, where if the CEO is engaged in something, it works differently than if it’s just a VP.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s return to the idea of institutionalizing the industrial policy muscle. I love that Fed analogy. This has come up several times on China Talk when thinking about China analysis or net tech assessment. I’m envious of macroeconomists — they have 400 PhDs just sitting there, clocking in at nine and out at five. Whereas the expertise on many of these other things, as you said, Ben, comes from great people cobbled together from various places – tech firms, investment banks, and corners of the deep state. What’s your plan to build the industrial policy muscle?

Ben Schwartz: First, you create an organizational structure designed to achieve specific purposes. If you’re trying to solve a particular problem, you ensure that the organization has all the necessary authorities and resources to solve that problem. For industrial policy, these are dispersed among multiple agencies in the U.S. government. You have USTR, the Treasury Department, and different parts of Commerce, each with their own responsibilities.

Who centralizes and manages the tools of industrial policy? Maybe the NSC, maybe the National Economic Council, or maybe a couple of strong leaders who assert themselves and try to herd the cats. That’s not a great way to do things; you should design a structure tailor-made to serve a specific purpose.

The second thing is about people, and this isn’t new. Some countries have set up systems to effectively do industrial policy. Singapore, for example, has a highly meritocratic civil service. They pay their people well, and the standards are rigorous. If you make mistakes, there are consequences. The reward is decent, and the consequences are significant. This keeps quality people in these jobs, and they don’t necessarily leave for the private sector because there’s something to be gained for them over time.

You need a personnel system that is sustainable and rewards talent.

Jordan Schneider: I was reading Project 2025 last night, and the Commerce Department chapter was interesting. On one hand, it suggested blowing things up, but there was also a part advocating for significant reorganization.

Commerce doesn’t really make sense in how its various authorities are spread out in different places. This person’s solution was to put a lot of stuff in USTR.

Regardless, it seems like the Commerce Department is ripe for some fundamental restructuring of what it can and can’t do, because historically it has been this big, weird agglomeration of different powers. I would vote in favor of giving it more tools. Do you think it should just absorb USTR? It’s kind of strange that USTR is its own thing.

Ben Schwartz: Upon opening that report, I quickly decided my time would be better spent with my children. Consequently, I set it aside and remain unaware of its contents.

Regarding the success of CHIPS, in addition to the secretary’s leadership and White House prioritization, we didn’t inherit an organizational structure designed for a prior purpose. Instead, we built a system specifically for this mission. While challenging because we were “building the plane as we flew it,” it was also liberating as we could create significant efficiencies.

Most government structures reflect historical needs, which don’t necessarily address current or future challenges. Organizational structures should be revised over time. In my experience, one of the most crucial aspects of any institution is aligning responsibility with authority. If you’re responsible for something, you should have the necessary authorities to meet that responsibility. These authorities shouldn’t be held elsewhere, preventing you from accomplishing your assigned tasks.

Jordan Schneider: The only other people I’ve encountered in government with similarly positive reflections are those who were in the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau during its early years, before it became politicized and imploded. It seems that organization was also created for a specific purpose and had special hiring authorities to bring on desired personnel.

To quote Jefferson: “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” Perhaps the tree of liberty also needs periodic refreshing with the hollowed-out husks of bureaus whose relevance have expired.

It’s been a long time since we’ve had a Goldwater–Nichols style hard look at bureaucratic structure and organization. Congress may be too dysfunctional to tackle something like this.

However, in this age of national competition, with China presenting a very different challenge than the Soviet Union did, we might need to reconfigure things from a bureaucratic perspective to respond appropriately.

Ben Schwartz: During my graduate education alongside distinguished military leaders, one wrote a lengthy essay called “Perpetual Adaptation.” This individual, with serious operational experience in complex war zones, argued that successful militaries adapt more rapidly than their adversaries. This lesson applies universally, including to bureaucracies.

You need stability to complete tasks, focus on the future, and maintain predictability. However, you also need the ability to adapt to changing situations. Government isn’t always as incentivized to do this as private industry, where failure to adapt often leads to extinction. Government lacks this imperative, sometimes requiring strong leadership to initiate change.

Over time, if you don’t achieve evolution, you get revolution. That’s how things work, and revolution is often bloody, as you mentioned.

Jordan Schneider: Got a song to take us out on?

Ben Schwartz: I did start a meeting with one of the larger companies where they had submitted a bunch of requests. I said, the theme of this meeting is from the Rolling Stones. You can't always get what you want, but you might just find that you get what you need. And I would say that the meeting proceeded as such.

Hopefully we'll get what we need here in Washington on chips and everything else!

Terrific discussion. Ben displays a level of optimism and positivity often sorely lacking from beaten-down government officials!

Whatever faults it may have, I fully expect that the CHIPS Act will be viewed in hindsight as one of the most important examples of industrial policy in the early 21st century.

This was excellent.

1. More of this

2. Share more broadly

3. More people working on this

We need it