The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy

My Fair Lady-ing guerrilla generals, Why Chinese diplomats can't get a date, and reading 100+ Chinese political memoirs

Why has China and its foreign ministry struggled to communicate with the world? In his book, China’s Civilian Army: The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy, Peter Martin (@PeterMartin_PCM) traces the history of China’s post-1949 diplomatic corps, from the impact of Zhou Enlai’s experiences in Paris to reluctant guerrilla-generals-turned-ambassadors trying to get to grips with manning embassies half a world away from Cultural Revolution China.

Along with Schwarzman scholar Jason Zhou, we dissect the international diplomacy up to Kissinger’s visit to China - but we’ll be looking at the establishment of US-China relations and onwards in part two!

Transcription and editing by Callan Quinn.

Peter Martin’s Hundred Memoirs Program

Jason Zhou: Why did you focus on writing about the foreign ministry? It’s not usually considered one of the stronger, more important government organs compared to some of the economic planning or security bodies.

Peter Martin: It's true that it’s a slightly weird topic. I had this general idea that I wanted to write a book on why China has struggled to communicate with the world. Obviously that was prompted by this moment in 2017 when there was this huge opening for China to step into the role that the US was vacating globally. To some extent it did with the Belt and Road and military modernization, but when it came to persuading others and winning friends, it didn't manage to step into that.

I was working in Beijing attending foreign ministry briefings and talking to lots to foreign diplomats, and I became intrigued by how Chinese diplomats might help to answer that question.

They have to inhabit two worlds at the same time: the close, secretive, paranoid world of Chinese politics and then the relatively much more open, cosmopolitan world of global diplomacy.

I figured that it would be interesting to delve into these people who had to simultaneously work both of those worlds and figure out a safe way to walk the line between them.

Jordan Schneider: Delve you did, reading over a hundred memoirs - and it really shows, which is fantastic. The first thing I do when I get a book about China is I look at the footnotes and if there aren’t many Chinese sources, I tend to put the book down. But your book is chock full of them though.

I imagine it was a real slog getting through a lot of it. What kept you going in this quest?

Peter Martin: Yeah. I guess you get better at reading the material, right? It was a real slog at first but then the vocabulary starts to get quite repetitive so it gets easier.

Even now under Xi Jinping, there is a huge amount to be gained from reading original Chinese sources. And I think that's true of any topic, whether you're looking at economic planning or diplomacy or military affairs.

I guess my slightly obsessive personality just kept wanting to keep going. I worked my way through them. I didn't finish though; there were dozens that I never got to. I've got a list somewhere in the bowels of my phone if anyone's interested in completing that.

Jordan Schneider: What was your selection process for who ended up on your bedside table?

Peter Martin: I wasn't particularly systematic about it. The whole time I was trying to build up this story that went from before 1949 till now. And so each time I picked up a book, I was looking for something that would help to fill in gaps.

Lots of them tend to have very lengthy cultural revolution treatments, which is great, but they'll skip over the eighties because the narrative tends to be ‘and then everything got better and China opened up and my life improved’. Which is true, but you want to know what was happening inside the bureaucracy and how that impacted the way that people talked about China.

In the nineties, Chinese diplomats found that on visits to places like Cuba they were getting questions about how the China model worked and they had only ever been in the ‘we need to learn from the world’ mode, right? That was like a little taste of what it was like to be from an economically very successful country and it was new for them. I really found a lot of pleasure in discovering moments like that and that kept me going.

Jordan Schneider: Is there anything particular about the genre of the Chinese bureaucratic memoir as opposed to Western diplomats or politicians talking about their lives that stuck out to you?

Peter Martin: It's more a question of rank. If you read memoirs by junior Western diplomats that are also not especially well edited, they're quite repetitive. When you get to very senior people, they're either ghostwritten or at least they're working with a high-profile publisher who's edited them really well.

I'd say that's true of Chinese-language memoirs as well. And then obviously in China you have the censorship factor too.

My understanding is that none of the senior people actually get to write their own books. They feed into a process with state-owned publishers where they talk through the content that they'd like to include and then there's a committee of people that produce the book in their voice for them. That's pretty uniquely Chinese.

Censorship changes a lot over time. Some of the books written in the nineties and the early 2000s are really quite thoughtful about reflecting on the role of the state versus the market, and what it means to tell a true version of history or to be a loyal communist party member.

None of these people are dissidents, right? They’re taking the official narrative of Chinese history and giving their own personal spin on it. But that's quite a bold thing to do in a system like China’s.

Books that have come out more recently are a bit more like ‘I want to thank the motherland and the communist party for fostering my professional development’ and much closer to Xinhua copy. But that makes sense given China's political change.

I enjoy putting ChinaTalk together. I hope you find it interesting and am delighted that it goes out free to eight thousand readers.

But, assembling all this material takes a lot of work, and I pay my contributors and editor. Right now, less than 1% of its readers support ChinaTalk financially.

If you appreciate the content, please consider signing up for a paying subscription. You will be supporting the mission of bringing forward analysis driven by Chinese-language sources and elevating the next generation of analysts, all the while earning some priceless karma and access to an ad-free feed!

The Structure of China’s Diplomatic Corps

Jordan Schneider: Did Zhou Enlai’s time with communist groups in France have any impact on the structure of the party and the foreign ministry?

Peter Martin: The structures of the communist party were inspired partly by the military. There was this whole kind of intellectual climate that went into Zhou’s thinking about the PLA as a model for Chinese diplomats.

The key characteristic that Zhou wanted to model was discipline. That was important for The PRC when it thought about putting diplomats out into the world because of the radical difference between home and the outside world.

At home they were focused on the control of information, of remaking society along incredibly radical lines. They were worried constantly about foreign plots and foreign interventions so they had to figure out a way to make that workable and square that circle.

That's one of the reasons the PLA jumped out as a model. Also the People's Liberation Army had just led China to victory in the civil war and so there was a great deal of bandwagoning.

Jordan Schneider: One of the fascinating things was this idea of doubling, where can't go out alone. It’s also something that the North Koreans do.

There was this great anecdote that you had where you write:

“The buddy system quickly became a part of daily life. Sometimes its implementation was even comical. When one trainee diplomat in Vietnam was asked on a date by a local woman in 1961, he immediately reported the invitation to his superiors. The embassy earnestly researched the woman's request and eventually ruled that he could go on a date as long as four other Chinese students accompanied him. He didn't get a second date.”

Where did this doubling idea come from and how does it sort of feed into broader themes of how the foreign ministry wanted to run itself?

Peter Martin: This is one of the types of weird questions that kept me going with the memoirs because it took me ages to track down where it had come from.

I'm still not sure exactly but my understanding is that this was an idea that Zhou Enlai had in 1949 and it was first implemented in the Moscow embassy by China's ambassador.

He insisted that he was accompanied by someone else as he walked around Moscow to make sure that there was no question of him leaking secrets or doing anything improper. And this was in the Soviet Union, which was at this stage supposed to be a close friend of the PRC.

It was something that was implemented in Chinese embassies across the world and has survived right up until today. The implementation has been spotty and imperfect, and has tended to be less closely followed at times when China's political system has been a little bit more open.

You can speak to former US and European diplomats who would go out for coffees with Chinese diplomats on their own and hang out in the nineties and the 2000s. They knowingly broke this rule. But under Xi Jinping, this buddy system has been implemented with extraordinary zeal, as you would expect. It's very much in fitting with the rest of the Xi project.

Jordan Schneider: Have you read Red Roulette yet?

Peter Martin: No, but I'm excited to.

Jordan Schneider: So in Red Roulette, Desmond Shum in his youth is running around Shanghai holding hands with his buddies and it's like the best time of his life. He spends the rest of his life searching for real friends. It's kind of funny thinking about this as like a horrible flip of that. Your ‘best friend’ could ruin your life and report you for talking to the wrong person or dating someone without approval.

Peter Martin: When you ask people what's it like to work in a system like this, oftentimes the answers you get are really surprising.

In the case of the buddy rule, I talked to Western diplomats who said they felt sorry for their Chinese counterparts, that it must be really embarrassing for them. That was my assumption as well. But when you talk to Chinese diplomats or former diplomats, they really liked the rule because it protects you. If there is a leak or something goes wrong, you have someone to vouch for you and you get to maintain your sense of innocence.

It shows just how radically different the incentives for individual behavior become in a system like this.

Jordan Schneider: The other buddy system that folks are probably used to is cops, right? That certainly happens in the West.

Peter Martin: Militaries use it too. Military attachés based in countries where there are worries about espionage will often go out and meet people in pairs.

Every diplomatic service puts restrictions on foreign contact or reporting requirements on foreign contacts. There's kind of a sliding scale but the PRC is way further along that scale than most.

How Guerrilla Fighters Became Cosmopolitan Diplomats - Or Not

Jordan Schneider: I want to take us back to the early years of the foreign ministry. There are these great Eliza Doolittle-type stories. These diplomats, many of whom did not speak any foreign languages, had to figure out how to make the transition from guerrilla to party-going jazz listener. What were some of the hijinks there?

Peter Martin: Zhou very deliberately picked, almost exclusively, PLA generals to act as ambassadors. These people had been fighting an underground guerrilla war for the last couple of decades so they were the last people you would send to cocktail parties. But that was the new task. Many of them were very unhappy about it and really fought in some cases to get themselves relieved of foreign ministry duty and sent back to the PLA.

Jordan Schneider: And of course the cushy capitals were not the the places that recognized China in the early years.

Peter Martin: I think China's first ambassador in Poland had his desk crafted from a door stuck on top of two bits of wood. These were not cushy jobs.

The process of getting these people ready to go overseas was incredibly daunting. There are examples from Hungary and also from Moscow where they found themselves sitting around idle in the embassy because they didn't really know what they were supposed to be doing as diplomats.

They went out and consciously had meetings with the Soviet foreign ministry and other diplomats from the Eastern Block and took notes on what the diplomats in an embassy do. Then they sent these notes back to Beijing and they were gradually compiled into training materials for the diplomats going overseas.

So there was that official side of getting them trained up. But there was also things like how do you eat? How do you make small talk? They held mock diplomatic receptions for some of these people in Beijing where they wore Western suits for the first time in their lives and they were taught to hold a knife and fork.

In many cases, they were instructed on what kind of questions you ask to keep conversation going and what you should avoid.

These lessons lasted for a long time. Li Zhaoxing, who was China's foreign minister in the early 2000s, recalled being told to not eat his food noisily, which he found really insulting at first. And then he realized that he did kind of slurp his noodles and maybe that it was a good lesson.

That stuff has obviously faded over time. They don't need to teach that now, but it lasted for a long time.

Diplomacy During the Cultural Revolution

Jason Zhou: What was it like for Chinese diplomats who were actually outside of China during the cultural revolution? You mentioned in the book that a number of diplomats were recalled to China. So who was actually in charge of the embassies?

There are some amazing anecdotes - one of the famous ones is about fist fighting outside of the Chinese embassy in the UK.

Peter Martin: Embassies were left with skeletal operations. At one point every single Chinese ambassador was back in Beijing with the exception of Huang Hua, who was in Egypt. There were a couple of diplomats who reflected on how Chinese embassies ended up feeling more like monasteries than embassies.

And at this time, there was such intense factional fighting in Beijing, even inside the foreign ministry, that they would get one cable with a set of directions one day and the next day something completely contradictory.

They could tell that something was going on, but they had no way of knowing exactly who was on top and exactly what they should be doing.

There were embassies where diplomats painted Maoist slogans in big red or gold letters on the outsides of the buildings, where diplomats went out and handed the Little Red Book out in the streets, even quite a few embassies where people started growing their own vegetables because they felt maybe they'd be politically safe if they showed that they were contributing to production and being workers rather than just diplomats hobnobbing with foreigners.

It was a pretty extraordinary atmosphere and many of those left overseas were also the most left wing and ideologically extreme people. When ambassadors were sent back overseas, many of them were pretty worried about facing these people and they didn't know if they were going to follow orders or if they were going to be hostile.

Jordan Schneider: It really goes to show the political Sword of Damocles hanging over all of these diplomats. On one hand, these are the lucky ones in the sense that they get to explore the world. Living as a poor diplomat in a rich country is very different than being stuck in Cultural Revolution or Great Famine China.

But at the same time, the fact that they had to live their lives attuned to all of this must have just been so cognitively weird for these folks, to be so subject to what was going on at home while being halfway across the world.

Peter Martin: And you have a situation where you can't trust the information that's coming from Beijing, but then you also don't really trust Western reporting on China either. Partly because from an ideological standpoint you shouldn't trust it, but also, practically speaking, in the cultural revolution no one had a clue what was going on so it might not even be reliable.

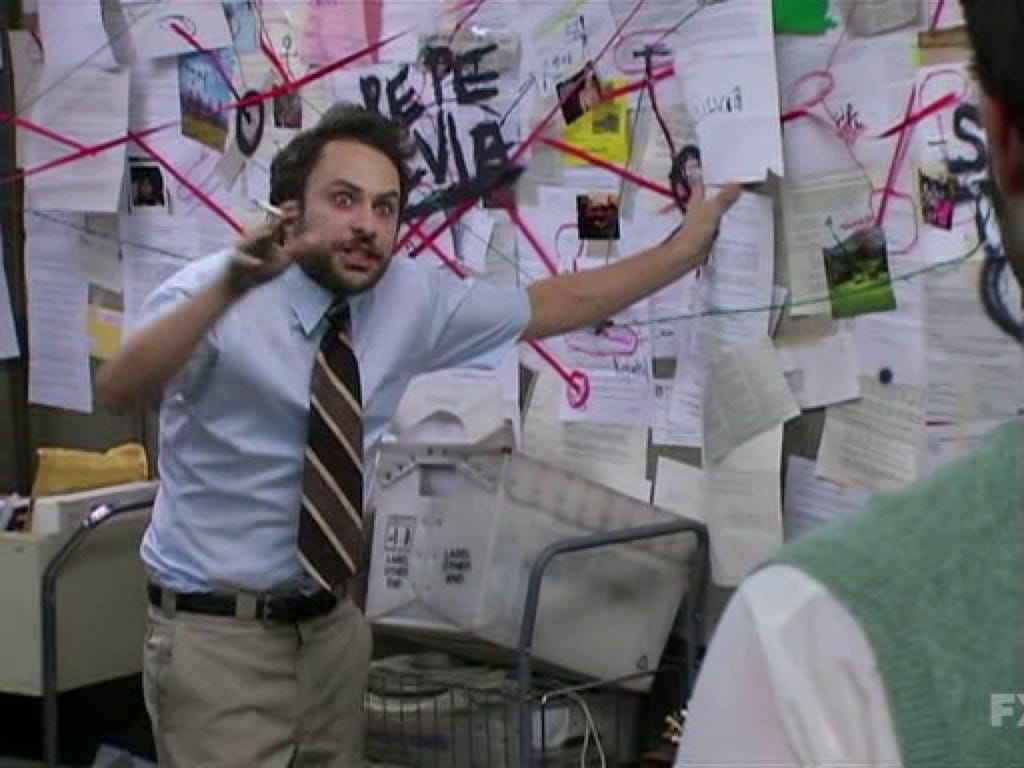

There were amazing scenes as people tried to figure out the demise of the Gang of Four. Western media had no clue what was going on. There was a lot of conjecture. They were receiving wildly contradictory messages from the foreign ministry itself. I think it was the embassy in Italy that had a display up on the wall where they had created something like from a cop movie where the detective has covered the wall of his apartment with all of the clues and laid out a timeline and stuff.

They had done that to figure out what was going on with the Gang of Four and whether they had fallen or not.

Jordan Schneider: In reading your book, you get the sense of stress that is really pervading these folks lives, especially once we hit the anti-rightist campaign and into the 1980s, which we will come to in our second episode.

Want more? The full episode with Peter is available here.

Thank you for reading. ChinaTalk grows only through word of mouth. Please consider sharing this post with someone who might appreciate it.