The Pentagon’s Innovation Insurgents

How to lose a war with China

In his book Engineers of Victory, Paul Kennedy argues that the most important historical variable for transforming resources into hard power is a culture of innovation.

How does one achieve one’s strategic aims when one possesses considerable resources but does not, or at least not yet, have the instruments and organizations at hand?

[The answer is] the creation of war-making systems that contained impressive feedback loops, flexibility, a capacity to learn from mistakes, and a ‘culture of encouragement’…that permitted the middlemen in this grinding conflict the freedom to experiment, to offer ideas and opinions, and to cross traditional institutional boundaries.

To discuss the Defense Department’s culture of encouragement, ChinaTalk interviewed Chris Kirchhoff.

Chris served on Obama’s NSC and was a founding member of the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU). He recently published a book called Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley Are Transforming the Future of War.

In our interview, we discuss:

The origin story of DIU and its early struggles to break Pentagon bureaucracy;

How DIU leveraged “waiver authority” to circumvent red tape under Defense Secretary Ash Carter;

Why the defense industrial base is ill-equipped to keep pace with technological change;

The case for shifting more DoD spending to non-traditional tech companies;

Lessons from commercial spaceflight for future AI governance, including potential issues with a “Manhattan project for AI.”

Secretary Ash Carter

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start with the origin of the DIU. What was Ash Carter’s vision and what was the pre-Ash version of DIU like?

Chris Kirchhoff: The story begins before Ash became Secretary of Defense. At the time, Pentagon leaders were wowed by the revolution in commercial technology in the 2010s. When I worked for General Marty Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, one of my first jobs was to organize a trip to Silicon Valley.

Marty Dempsey is an extraordinary leader, and he had what he called his “campaign of learning.” At our first event, a breakfast with Vint Cerf and other tech luminaries, General Dempsey announced: “I’m here on my campaign of learning. If I don’t learn something, Chris gets fired.”

But what’s most memorable about the trip was our visit to Google, where we met with Astro Teller, head of Google X. Teller briefed us on their self-driving car project, which is now Waymo. One of the test cars, a Prius with a lidar dome, was parked next to our motorcade.

As we were walking back, General Dempsey said he wanted to go for a ride - which was absolutely not the plan given security protocols. But Dempsey got in the backseat and drove off, leaving me thinking I was definitely going to be fired.

He came back after 15 minutes, having watched the Prius navigate autonomously and maneuver around a cyclist. Dempsey asked the key question: “How much does all this hardware cost?” The engineers answered, “About $3,000.”

You could see the lightbulb go off in Dempsey’s head. This revolution in consumer electronics wasn’t just about smartphones — it would impact the military as well.

Jordan Schneider: When you think back about various revolutions in military affairs across history, where some people “got it” and others didn’t, what separates those who understand the future from those stuck in the current paradigm?

Chris Kirchhoff: You have to be modest — it’s easy to view the current push to link consumer and military tech ecosystems as unique. But the more military history you read, the more you realize the deep continuity with the past.

What’s different now is the relative scale. Today’s consumer tech market is $25 trillion. The Pentagon buys a lot of stuff, but we’re talking billions, not trillions. Never before has the commercial innovation ecosystem been so much larger than the defense ecosystem. That’s the generational shift Ash Carter spotted and acted on.

Jordan Schneider: If you think about precision targeting in the 80s and 90s, it wasn’t the DoD pushing shrinking nodes, but the relative balance between commercial and defense R&D was much closer than today.

Chris Kirchhoff: Exactly. That brings us to Ash Carter. In a 2001 article as a professor, he hypothesized that growth in commercial tech would quickly make that ecosystem so much larger than defense that it couldn’t be ignored.

With post-Cold War drawdowns in federal R&D, Ash realized DoD needed to shift to being a fast follower rather than always being generations ahead. He saw this clearly in 2001 and shortly after becoming Secretary moved to create the Defense Innovation Board and DIU.

Jordan Schneider: You have great stories about the outdated tech in military facilities circa 2016. To paraphrase some anecdotes, your co-author Raj Shah visited a command center that “was as if the military had resigned itself to becoming a display in the Museum of Computer History.” Trae Stephens, who co-founded Anduril, said of his early days in intelligence: “20% of my time was merging database files. I thought I’d be doing James Bond stuff with supercomputers. Instead, it was a joke.”

The most interesting part of DIU version 1.0 was that Congress tried to pull the plug and defund the program, which motivated the reset. What drove you and Raj to ultimately get on board for the reboot?

Chris Kirchhoff: It goes back to leadership. Ash Carter is a serious guy who doesn’t miss much. When he heard DIU wasn’t succeeding, he sent Todd Park to investigate firsthand. That says something about how Ash approached his job — not leaving anything unnoticed.

I credit Ash for realizing DIU’s initial incarnation wasn’t set up to succeed, going back to the drawing board, and thinking hard about how to make it work.

“To the extent present military and civilian leadership is articulating its strategy, it is one built, for the most part, on a continuation of previous programmatic and budgetary trendlines.

If there is a strategy for losing a future war in China, this is it.”

- Chris Kirchhoff in Unit X

Hacking the Pentagon Bureaucracy

Jordan Schneider: Can you tell the story of the “term sheet” you crafted at the beginning to set DIU on a path where it could potentially succeed?

Chris Kirchhoff: When Secretary Carter approached us about potentially leading the DIU reboot, we’d already watched the first team struggle. During an earlier visit to their office, I remember literally sitting on folding chairs for our briefing, thinking “I’m glad I didn’t come work here."

Raj and I carefully considered what would be needed for success in the reboot.

First, we needed personal commitment from the Secretary of Defense. We needed his personal buy-in to our unit because we knew how difficult the internal struggles would be. Working closely with the Secretary and his staff was critical to avoid being buried under layers of bureaucracy.

The second key item on our term sheet was “waiver authority.” This was a new idea in the department. The concept was that if you hit a policy or procedure (not a law) squarely blocking your mission, you could request it be waived.

Under the policy we set up, the owner of that policy had 14 days to handle a waiver request. If they declined, it would go immediately to Secretary Carter for review. This was an incredible bureaucratic weapon because now anyone who wanted to block us would have to answer to the Secretary of Defense.

That waiver authority ended up being the most important early tool we had at DIU.

Jordan Schneider: It’s striking that waiver authority and Other Transaction Authorities (OTAs) are basically ways to avoid doing things the way everyone else does. Thinking back, to what extent would you keep any of these rules if you could start from scratch?

Chris Kirchhoff: The challenge in any public sector institution is that you can’t really start from scratch. Our government doesn’t allow experimentation easily by design.

But at DIU, we tried to look afresh at what was possible. We had this phrase among our group of change agents: “Just legal enough.” ‘

There’s often an enormous distance between the strict letter of the law and where the practice is.

“Can we do this acquisition faster? Is that legal?”

“Just legal enough.”

The most incredible example is Lauren Dailey, an acquisition dynamo. Her father was a tank driver, and her way of serving was to become a civilian acquisition expert in the Pentagon.

She stayed up late reading the text of the just-passed National Defense Authorization Act and found a single sentence that would change how OTA contracting could be done. It allowed the immediate conversion of a successful OTA pilot into a production contract.

This was a game-changer. Before, if you were a firm and got an OTA, there was no real path to go from a one-off technology pilot to something at scale. Lauren brought this to our attention, and we took it all the way up the chain.

In just over two weeks, we got everyone to agree on a whole new process for OTAs which we called the Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO). That allowed DIU to crack the hardest problem we faced - how to let contracts at Silicon Valley speed.

Jordan Schneider: We’re recording this July 3rd. Everyone across the executive branch is wringing their hands about the Supreme Court’s Chevron decision. Have you put any thought into this? Will this change help the DoD to shed some of its shackles?

Chris Kirchhoff: Well, I’m no lawyer, but I think Chevron will be much more disruptive for regulatory agencies. I’d be interested to learn what the exact implications are for the Department of Defense.

But it’s a general reminder that institutions tend to accumulate rules and procedures over time — and those might not serve their evolving goals. Leaders should consider what they can discard when trying new things.

Jordan Schneider: In the book, you point to an internal vetocracy in the DoD. If you want to do something, you actually need 20 people to not be upset with you. We see similar vetocracies across government with permitting for data centers and so on. There are many veto points where someone can block progress if you haven’t sufficiently convinced them of your vision.

Your theory of success required the buy-in from the person at the very top. What are your recommendations for bureaucrats at the other levels, who don’t necessarily have the Secretary backing them in every knife fight?

Chris Kirchhoff: I’ll explain with an anecdote. In the first couple of months at DIU, Ash Carter became aware of how little time he had left as Secretary. He wanted to make progress every day, which meant he sometimes moved incredibly fast.

Just after Raj and I were appointed, we got a call saying the Secretary was visiting Boston in three weeks and wanted to open a DIU office there during the trip. They also wanted us to have our official charter ratified by then.

Suddenly I found myself in the basement of the Pentagon with the office that writes charters for OSD entities. They have an elaborate process involving circulating drafts to hundreds of offices, any of which can object.

I asked, “What’s the fastest you’ve ever put a charter together.” They said 18 months for JIEDDO during the Iraq War, which they viewed as a land speed record.

I had to uncomfortably push back and say, “The Secretary wants this in 3 weeks.”

One person raised their voice, insisting it was impossible. I had to respond, “I’d be happy to personally tell the Secretary that you said it couldn’t be done. Is that the message you wanted me to deliver?”

Ruffling feathers like this is uncomfortable but necessary.

We didn’t have the charter ready for Boston, but we had it not too many weeks after. That shows what leadership can do.

In the years after Secretary Carter departed, DIU quickly began to struggle, despite the fact that it did have a lot of support at the top, particularly under Secretary Mattis.

In public institutions, leadership is absolutely essential.

Artificially Unintelligent Institutions

Jordan Schneider: How much can AI reduce paperwork?

Chris Kirchhoff: An OSD AI official recently said to me, “Can you imagine if we had ChatGPT at our desktops? For OSD policy offices that spend most of their time writing briefing memos, reports, and template-compliant staff update emails — can you imagine how much faster they could work with LLM support?"

Even though we now have an entirely new office dedicated to this (the CDAO), it’s still remarkably difficult to make AI work in the public sector.

Any employee of a Fortune 100 company likely has a suite of AI tools at their desktop. In theory, people in OSD policy do as well, because the Pentagon decided to build a bespoke custom AI interface just for the DoD. Rather than buying something off the shelf like every Fortune 100 company in the country, we’ve made the problem harder for ourselves.

We still have a long way to go.

Jordan Schneider: I’m going to quote a show I did a few months ago with Garrett Berntsen of the CDAO:

Garrett Berntsen: In my perspective, having done this for a bunch of years now — that group of folks in the department is so stretched just trying to keep the lights on and get paper out the door. When faced with the prospect of taking on a new thing that’s going to be innovative and cool they’re like, “I don't know if I've got time to do that,” even if it would save them time in the long run.

… They’ve seen a ton of waves of this before. They’ve seen a lot of these, “we're going to modernize everything with X new tool,” 15 years ago. When e-mail rolled out, they were told that it was going to make everything easier. Instead, it’s made their lives an endless cycle of responding to e-mails.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s go a little sci-fi for a second. Beyond just having ChatGPT give you four paragraphs on what’s going on in Pakistan, are there other back-office applications of AI that you’re particularly excited about?

Chris Kirchhoff: Well, I’m sure there are many, and my greatest hope is just that the Department of Defense seizes the opportunity to experiment with AI, increasing their productivity, and making it easier for their employees to do knowledge work.

This is an incredible opportunity for the department, but again, DIU was created for a reason. There’s a beautiful quote in the opening of our book from Chris Brose, the longtime staff director of the Senate Armed Services Committee and now head of strategy for Anduril:

[T]he second decade of the twenty-first century was one of colossal missed opportunities for the US military. DoD, on the whole, had missed the advent of modern software development, the move to cloud computing, the commercial space revolution, the centrality of data, and the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. This was the case despite having funded the fundamental research that led to many of these advances. DIUx and DDS were to change this by placing DoD personnel directly in the commercial technology ecosystem.

The track record isn’t great. That should be foremost in mind of not only the current Secretary and Deputy Secretary, but the next several.

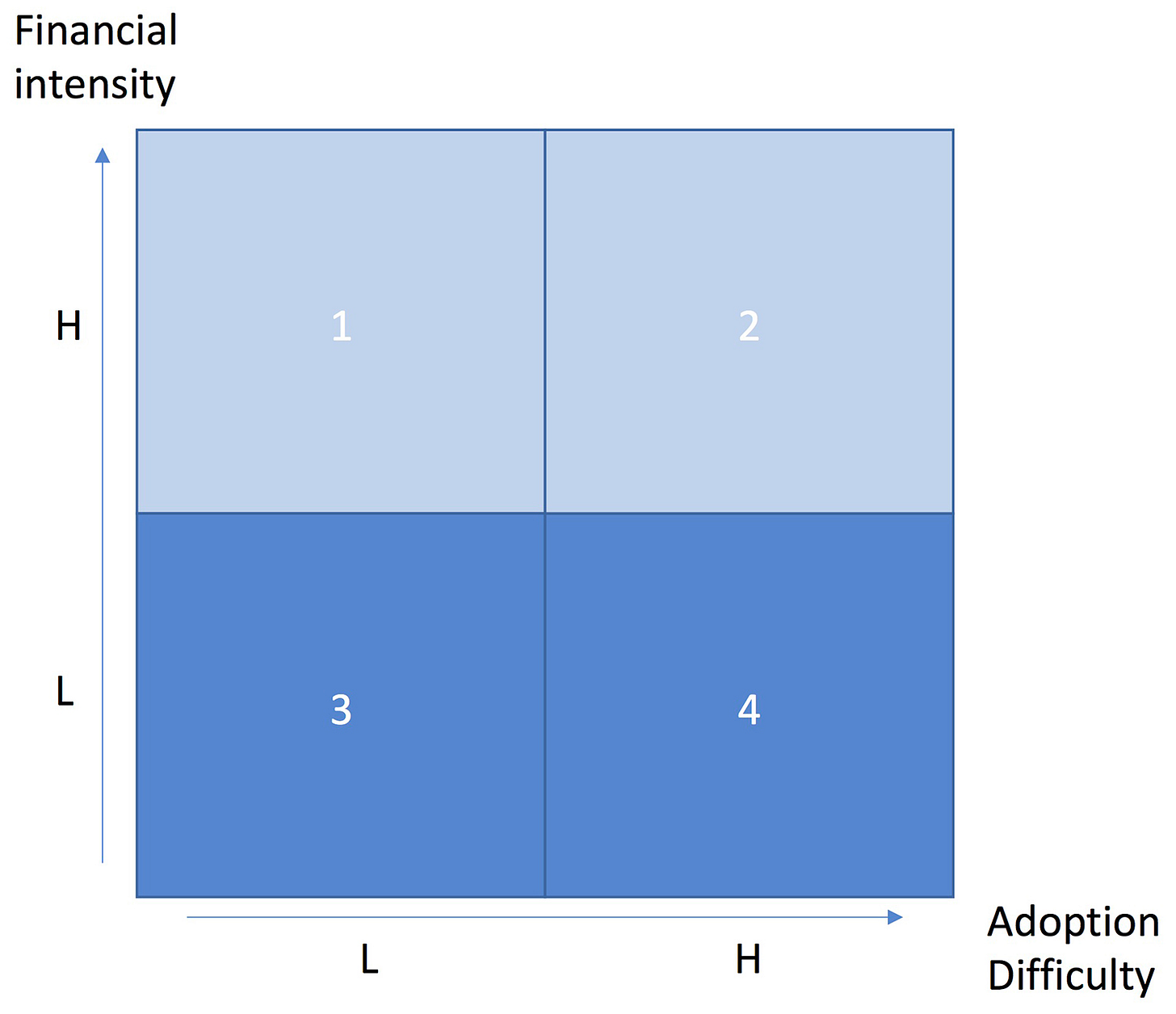

Jordan Schneider: Mike Horowitz, who is now working on emerging technology in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, previously wrote a book where he describes a two-by-two matrix for the level of organizational capital required to implement a major military revolution, versus the level of financial intensity.

Basically, if an innovation is easy and expensive, then this is something that the US is particularly well-suited to working with. But innovations in quadrant 4 are difficult even though they don’t require a ton of money, but rather require you to reimagine your current bureaucratic infrastructure. Those types of changes are much more difficult for a leading global hegemon to internalize.

Chris Kirchhoff: I admire Michael Horowitz’s scholarship. His work on innovation adoption is essential reading, and in fact we cite it in DIUx. The reality today, as we’re learning so brutally in Ukraine, is that inexpensive technology is quite potent and powerful.

But today, what’s perhaps more relevant than the size of the investment, is whether it needs to happen through traditional budgeting channels or through new channels with which the department is not as comfortable.

In other words, it’s really easy for the Navy to buy another aircraft carrier. They know how to do that. They’ve been doing that for a long time. There are very few suppliers, there’s a very set schedule for getting something like that through Congress.

But at smaller levels, what if you want to buy 1,000 drones and experiment with them? Which category of funding and which program office does that?

It could be that there isn’t one and you actually have to create it.

Technology shifts have thrown us into a place where a lot of the department’s traditional processes are simply not applicable. That’s very uncomfortable for the institution. But of course, if you ignore that, you do so at your peril, because for every day you’re not fixing that and addressing that, you’re falling further behind the technology power curve.

DoD doesn’t have an innovation problem; it has an innovation adoption problem.

There’s plenty of incredible technology floating around the department at places like DARPA and now at DIU. But getting it to work at scale is not something the department does well.

Jordan Schneider: I want to throw two more quotes at you. First is from Bill LaPlante, who’s the most important acquisitions leader in the defense department:

Bill LaPlante: Ukraine is not holding their own against Russia with quantum. They’re not they’re not holding their own with AI.

…

It’s hardcore production of really serious weaponry. That’s what matters. Not to say that we shouldn't invest in quantum or we shouldn't invest in AI. I'm not at all saying that.

…

If somebody gives you a really cool liquored up story about a DIU or an OTA, ask them when it’s going into production, ask them how many numbers, ask them what the unit cost is going to be, ask them how it will work against China.

…

And don’t tell me it’s got AI and quantum in it. I don’t care.

The second quote is from Alex Wang, CEO of Scale AI:

Alex Wang: It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to realize that powerful AI systems, if they existed, would be a definitive military technology.

You could imagine that nuclear deterrence doesn’t even really matter in a world where you have advanced AI systems.

They can do superhuman hacking. They enable autonomous drone swarms. They can give you full situational awareness, they can develop biological weapons.

You can diffuse and perhaps neutralize an enemy’s nuclear arsenal.

Everyone within the national security community in the United States needs to understand, grok, and pay attention. This is a Manhattan project-level of technological capability.

Chris, thoughts on what these two mindsets tell us about the future?

Chris Kirchhoff: Well, I think there’s clearly a tension between those two views. Traditional weapon systems still have incredible relevance in Ukraine and elsewhere. At the same time, when we visited Ukraine, it was just astonishing to see the digital overlay that has been built around artillery, tanks, and trenches - things that have been around warfare for a very long time.

It really is going to be the synthesis of these two things where you’re going to see new combat power materialize. Ukraine, as horrific as the human disaster has been, has been a real wake-up call.

Jordan Schneider: The thing that Bill LaPlante sort of misses in that quote specifically is the idea that all that technological overlay is almost like table stakes. You have to have it in order to play the more traditional game of attrition with guns and old dumb artillery shells.

We’re clearly not in the world of Alex Wang’s future, where all you need is great technology and you’ll be able to achieve costless victory. But to completely dismiss the role that the tech bros are playing, I think, is also really missing what’s happening in the present and the future.

Chris Kirchhoff: That takes us back to the cover of the book. Even though the F-35 didn’t become fully operational until 2016, it’s still operating off of PowerPC processors. By 2016, we already had fifth-generation iPhones. It’s a stark reminder of how quickly technology moves compared to traditional defense acquisition cycles.

Lessons from Commercial Space for AI Governance

Jordan Schneider: We’ve seen an interesting arc around national security and AI labs over the past 18 months. More of the world, and the labs themselves, are waking up to the fact that AI is perhaps one of the most important dual-use technologies that will matter in coming years.

There’s increasing awareness around lab security issues and a steady bifurcation of the Chinese and US AI ecosystems. The current discussion among those who claim to be serious about national security assumes we’ll end up in a world where AI development is nationalized like the Manhattan Project.

The counterargument is that the private sector will end up doing whatever it wants. An interesting middle ground is the arc of the US space industry. What lessons do 20th and 21st-century commercial space hold for the future relationship between AI labs and government?

Chris Kirchhoff: My former colleague at Anthropic, Michael Page, made an interesting observation that commercial space could provide a model for how the US government handles increasingly sophisticated AI.

I’ll tell a quick story. My first job out of college was working on the Space Shuttle Columbia accident investigation. Space shuttles were an incredibly dangerous experimental technology - there are 5,100 critical failure points.

When I was working on that investigation, the idea that a private company could successfully launch people into space seemed far-fetched, maybe even insane. It seemed like you needed the full expertise of government to underwrite that kind of dangerous experiment.

For the next few years, I looked skeptically at the arrival of commercial space companies like SpaceX. I thought they were doomed to fail - that there was no way to improve on the engineering baselines that NASA engineers had labored for decades to achieve.

I turned out to be wrong.

SpaceX is wildly more successful at safely launching things into space — and at far lower cost than any government launch — with more or less the same tools NASA had all along.

This becomes relevant to AI, which unlike many advanced technologies has grown almost exclusively in the private sector. That’s after decades of government R&D contributions, but in terms of who’s operationalizing it now, it’s largely private companies.

Could NASA’s model of outsourcing launch to the private sector, with minimal engineering oversight of spacecraft operations, be a model for harnessing the nation’s AI capabilities? Could the government bolt onto itself private AI companies, rather than needing in-house AI development through national labs or another vehicle?

Jordan Schneider: The OpenAI and SpaceX stories are fascinating parables of organizational design. OpenAI didn’t have more compute than anyone else in 2017-2018, but they had the institutional freedom to take different bets than Google. SpaceX could innovate in ways Boeing couldn’t.

Chris Kirchhoff: Yes, and this is important to point out to those who hold up the national labs as a potential model for AI.

The national labs do incredibly important work in many areas. But that said, who produces more peer-reviewed publications, Google or the national labs? My money would be on Google.

The message here is that the private sector has proven to be an incredible national advantage for America. The free market has allowed a flourishing of research and development, particularly in the last two decades, that is just unparalleled.

I mean, DIU had to struggle so hard to pay advanced AI engineers half the salary they’d receive at a tech company.

We broke or nearly broke all the rules in the book, and we still had to convince people to take a 50% pay cut to come and work on the Department of Defense’s AI mission.

That makes me very cautious about those who view the national labs as a kind of turnkey solution.

Jordan Schneider: Chris, you wrote, “Unlike China, we have a system where information flows freely and where competition ensures that the best ideas and products rise to the top.”

Do we though?

Chris Kirchhoff: Well, the whole point of writing the book was to substantiate that claim. My co-author, Raj Shah, now runs Shield Capital, the first venture capital firm dedicated to companies that can contribute to national security.

The defense industrial complex is termed a “complex” because it’s not a free market in the sense that none of the major primes are product companies. They respond to a different set of incentives. They are saddled by the Department of Defense and the federal acquisition regulations and a different set of requirements for auditing and accounting.

They cannot operate like Google, Microsoft, or OpenAI, and they most certainly cannot operate like a startup. The debate we need to be having at some level is — how much of our defense spending do we want to go into institutions in that complex, and how much money do we want to shift into the free market innovation economy?

Jordan Schneider: Ultimately, this debate is going to get hashed out in Congress. What is it going to take for Congress to see the world in your way?

Chris Kirchhoff: On day two of our jobs, Raj Shah and I were saddled with the knowledge that Congress had just cut our entire budget, the whole thing, and that unless we hustled and really pulled a rabbit out of a hat, DIU would cease to exist.

The good news is, since then, there’s been a real swing of support towards the idea that the right thing for the Department of Defense to do is to access Silicon Valley and more technology from it.

In fact, in last year’s NDAA, we actually saw the Defense Innovation Unit get codified in law. Not only that, Congress bestowed upon it a budget of just under a billion dollars, which is really exceptional.

Even with such tremendous progress, only a very small portion of the Department of Defense’s budget goes to the new defense economy. Unless we change that, we’re increasingly going to find ourselves surprised.

We’ll be surprised by what’s happening in Ukraine, surprised by Hezbollah’s use of loitering munitions to depopulate northern Israel, surprised by Hamas using quadcopters to knock down Israeli border towers to enable 1000 fighters to pour over a kind of modern-day Maginot line.

We kind of ignore this debate, I think, very much at our own peril.

The Human Toll of Public Service

Jordan Schneider: One of the things I appreciated you writing about is the toll these jobs take on the people who want to do them well. Would you like to talk a bit about your experience?

Chris Kirchhoff: I left DIU in 2017 when the Obama administration stepped down. I was pretty sure I was done with full-time public service. I had given thirteen exceptional but also exhausting years.

The semester after I left, I taught undergraduates at Harvard. Many took my class because they aspired to work in national security. From their perspective, seeing pictures of me with President Obama in my office, it must have looked amazing.

But during office hours I had to tell them: It is wonderful. You get to work on incredibly important problems with real-world impact. It’s gratifying to use your political science training to make the world better.

But there are things you can’t unsee. I used to get an email before every US drone strike.

Whether in uniform or as a civilian, when that’s your day-to-day, it takes a toll. That weighed on me when I left DIU. I was almost positive I’d never go back into government. But you never say never.

The day I was most tempted was when Ron Klain, a former boss I really admire, was announced as the next president’s chief of staff. I thought hard about going back in. I called my oldest mentor, and she asked me three questions. The conversation went like this:

What do you actually remember about the last time you were working at the White House?

Driving home at 2 am. I was so tired that all I could think about was trying not to crash my car into Rock Creek Park.

How long ago was your divorce finalized?

About a year. I was with my first husband for 13 years. Not coincidentally, we had separated not long after my time in public service ended.

Are you ready to leave San Francisco? Haven’t you just met someone new there?

The answer was no, I wasn’t ready to leave.

In three minutes, she helped me realize that. I share that story with purpose, because it’s important for people to realize the joys but also the burdens of serving in national security.

Jordan Schneider: You can’t completely remove people from involvement with life-or-death decisions at the Department of Defense. But then there are also stories of George Marshall playing afternoon golf during World War II.

I’m curious, what percentage of those 12-16 hour days actually needed to be worked? If the whole place ran better, might people be able to sustain themselves longer?

Chris Kirchhoff: You’re part of a system and a team, working collectively to help leaders make the best decisions possible.

That’s why it’s hard to go home at 5:30 pm in these jobs - you simply don’t want to do anything but your best.

But in addition to the tough days, there are also some incredible ones.

As the science nerd on General Dempsey’s staff, he asked me to closely track Ebola back when it was still a small outbreak in West Africa. The WHO maintained it was under control, but Dempsey wanted someone watching in case it became an emergency requiring military capabilities.

Fast forward a few months, and we went from a small outbreak to one threatening global security. Thanks to the pre-planning that summer, we had options ready for the Secretary and President on how the military could help.

That led to Operation United Assistance, which deployed 3,500 US service members to support 100,000 medical first responders in West Africa. That operation ultimately ended the Ebola epidemic.

Late in the outbreak, I traveled to West Africa with a White House delegation. I got to meet people who survived Ebola because of what DoD did. All you could do was hug people and cry because you had done something incredible for them and for America by helping stave off a global threat.

The job is full of sorrow and joy, and it’s all incredibly meaningful. With any luck, you do a lot of good even on the worst days.

Jordan Schneider: Chris, you just finished a policy residency at Anthropic. Why were you more interested in working at a lab?

Chris Kirchhoff: I really enjoyed my time at Anthropic, and I actually got to work there on a number of national security issues, including policy issues and issues of practice with Anthropics AI safety team, which they call their Frontier Red team.

I’m really excited to keep working in this area because I think generative AI will have a tremendous impact on American military capability. There are many opportunities but also many risks that need to be managed.

Jordan Schneider: Can you give us some book recommendations to take us out?

Chris Kirchhoff: I’ll give you three.

The first is called Tracers in the Dark: The Global Hunt for the Crime Lords of Cryptocurrency by Andy Greenberg. It’s an absolute page-turning barn burner of a story about crypto lords trying to hide their tracks from law enforcement, and the FBI agents who are hot pursuing them.

It’s a story about state sovereignty in the technological age, exploring whether states have the capacity to enforce the rule of law when criminals are backed by such sophisticated technology. You will tear through it. You won't be able to go to bed.

The second book is Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland by Patrick Radden Keefe. It’s an incredible history of The Troubles in Ireland, based on oral history and a set of interviews that journalists had never accessed before.

It paints this heartbreaking picture of violence between two groups who were sorting out their political institutions. In a strange way, I felt like the United Kingdom went through its own version of the Iraq War in Ireland — Ireland was kind of like Al Anbar, and the British military came in to try to pacify things, using violence that turned even more people against them. In terms of the sociology of violence and the sociology of conflict, it’s a tremendous read.

The last book is Malcolm Gladwell’s Bomber Mafia: A Dream, a Temptation, and the Longest Night of the Second World War, which is best consumed as an audiobook.

Gladwell paints these vivid portraits of characters during WWII. You see history through the eyes of soldiers and air force bombers, in both the Atlantic and the Pacific theaters.

Bought Unit X thanks to this - looking forward to reading! Timely for a course this fall