This is a guest piece by JS Tan, a PhD Candidate at MIT’s international development program, researching the political economy of innovation in the US and China with a focus on cloud computing. He was previously a software engineer and writes on Substack here.

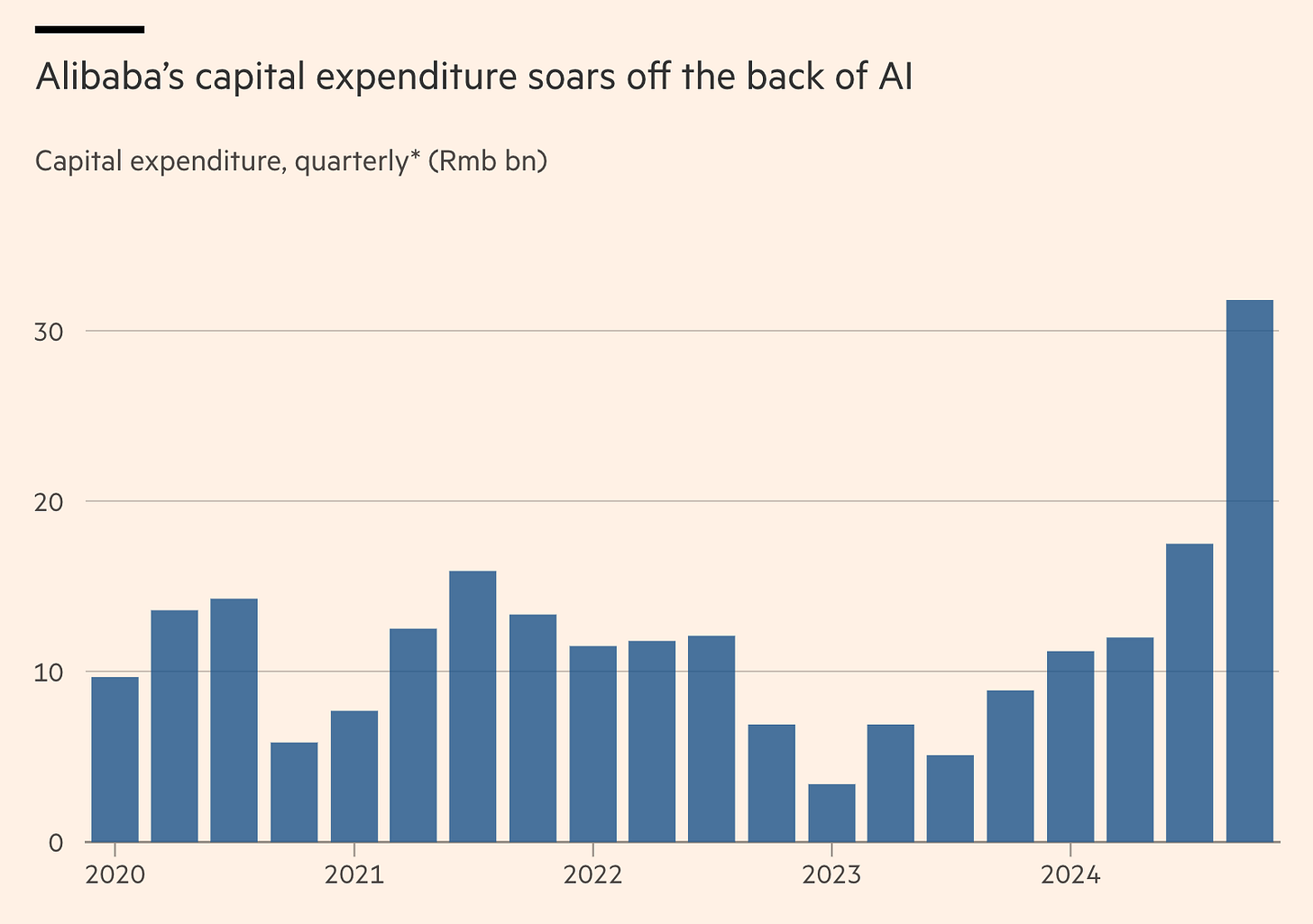

Alibaba’s recent commitment to invest $53 billion in AI and cloud infrastructure — surpassing its total AI and cloud spending over the past decade — marks a major bet on the future. This investment signals not only Alibaba’s confidence in AI-driven growth but also its recognition that cloud computing will be a central pillar of the digital economy. Once battered by regulatory crackdowns and slowing profits, Alibaba is now doubling down on AI infrastructure, aiming to secure its place in China’s rapidly evolving tech landscape.

However, AI’s transformative potential — especially its diffusion across industries — ultimately depends on the strength of the underlying cloud infrastructure. Whether Alibaba’s aggressive AI push and massive data center investments will translate into higher profit margins for the company or a more competitive Chinese cloud sector as a whole remains an open question. And even though Alibaba is best positioned to play a critical role in AI's diffusion in the country, what’s missing from the FT’s analysis is a broader political-economic assessment of China’s cloud industry and the institutional factors that strengthen, or in some cases, constrain the country's cloud ambitions.

This article explores why low-margin compute and a non-existent SaaS ecosystem leave China behind in the cloud — and why this might not matter much to Beijing.

How Far Behind Is China?

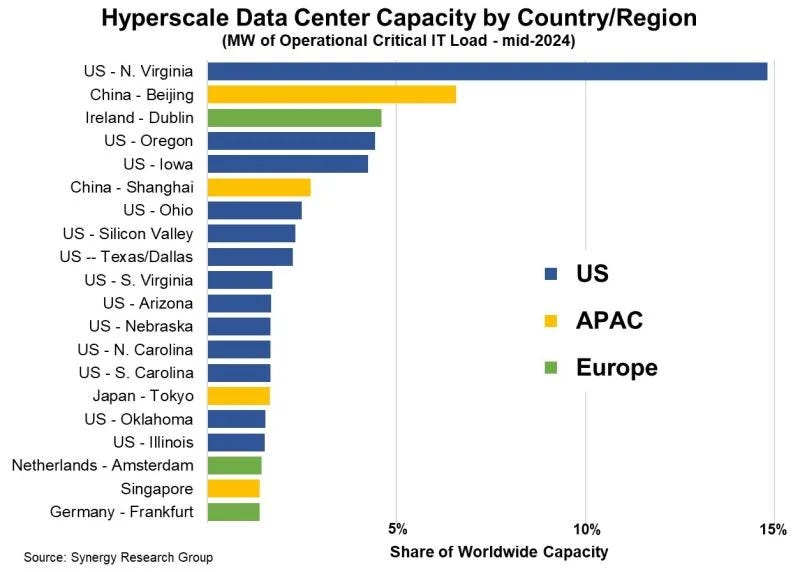

To assess the political economy of China’s cloud sector, we must first understand the global competitive landscape. The U.S. cloud industry is dominated by three major players: Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. China’s cloud industry follows a similar pattern. Alibaba Cloud and Tencent Cloud lead the market, mirroring Amazon and Google’s dominance. However, the Chinese industry lags far behind. A key measure of this competitive gap is revenue. By this measure, U.S. cloud providers dominate by a wide margin — AWS alone generates more revenue than the entire Chinese cloud sector combined. The disparity is also evident in data center capacity. The U.S. accounts for 51% of the world’s data center capacity, while China lags behind at 16%.

A major distinction between the U.S. and Chinese cloud sectors is the role of telecom firms, which have more experience, when compared to internet companies, at building physical infrastructure. Unlike the U.S., where no telecom company has successfully entered the cloud market — AT&T attempted but later sold its assets to IBM — China’s cloud sector includes firms with deep expertise in telecommunications. Huawei, China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom have all invested heavily in cloud computing, leveraging their existing network infrastructure to expand into the sector.

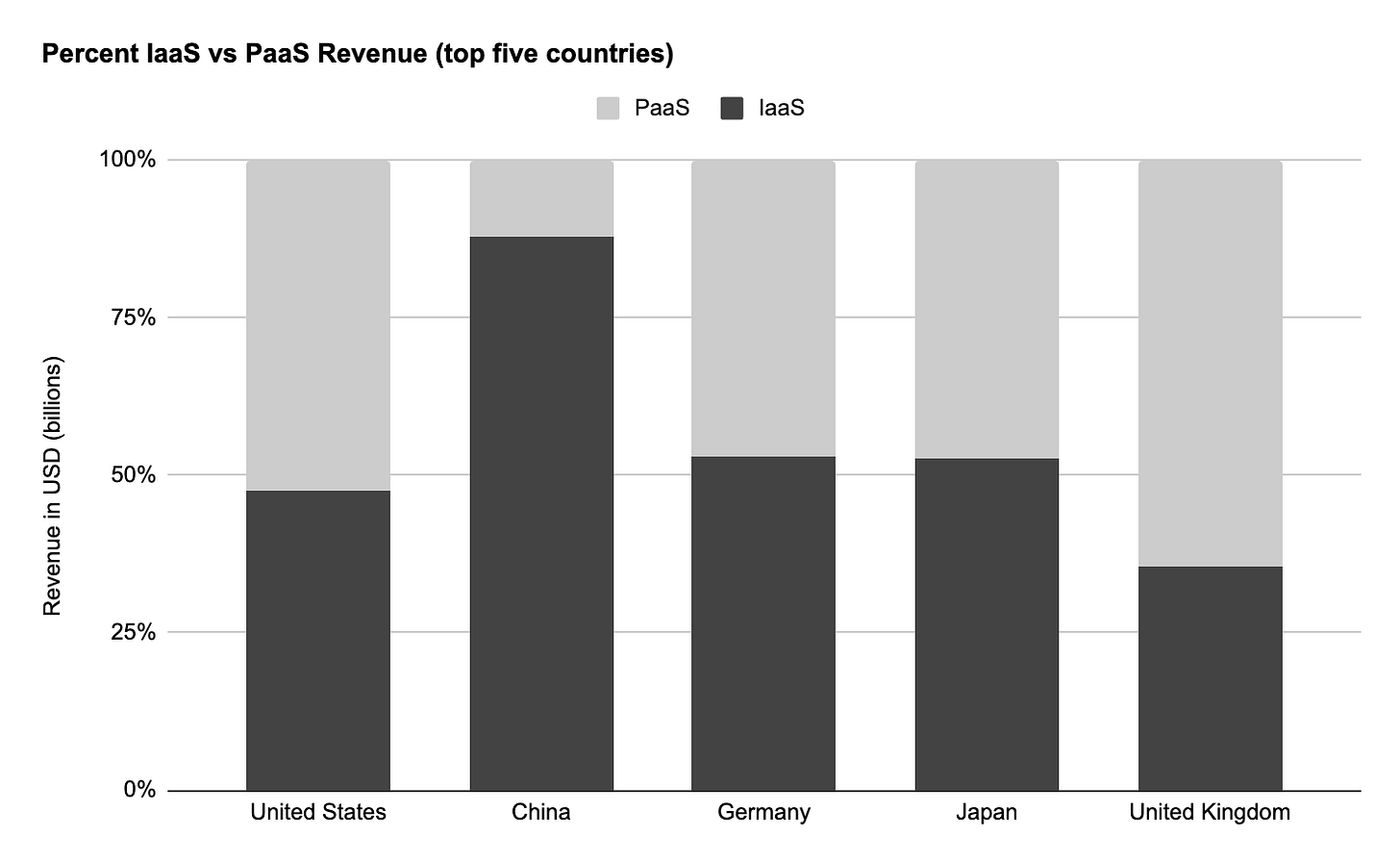

Revenue and infrastructure alone do not fully explain the structural differences between the two cloud industries. A deeper distinction emerges when breaking down revenue by cloud service type: Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) vs. Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS).

IaaS consists of the basic building blocks of computing — compute, storage, and networking — delivered as virtualized infrastructure. Because IaaS is more about lifting existing IT operations onto the cloud, it requires less business transformation and is easier for firms to adopt. PaaS, by contrast, is more software-driven and involves deeper integration into enterprise operations. It is more profitable for cloud providers since it enables higher-margin services, such as AI platforms and business analytics.

While both the U.S. and Chinese cloud providers derive most of their revenue from IaaS, U.S. firms are far ahead of Chinese ones when it comes to revenue from PaaS. To this day, Chinese cloud firms are disproportionately reliant on low-margin IaaS, making its cloud providers more akin to commodity infrastructure providers rather than enablers of productivity-enhancing digital transformation.

Why Has China Fallen Behind?

A fundamental weakness of China’s cloud sector is low IT spending. A 2014 McKinsey report found that Chinese firms spend only 2% of their revenue on IT — half the global average.1 Historically, businesses have been reluctant to invest in IT due to high costs and uncertain returns. IT spending — whether on enterprise software, better infrastructure, or cloud services—is intended to improve productivity, but such gains aren’t immediate or guaranteed. Successful cloud adoption depends on structured data, formalized business processes, and standardized workflows — conditions that many Chinese firms lack.

Moreover, China’s low labor costs and weak labor protections reduce the incentive for businesses to invest in IT infrastructure. When labor is cheap, firms can simply hire more workers instead of upgrading their IT systems for uncertain productivity gains. As a result, many Chinese businesses use cloud computing only for basic, low-cost functions (such as website hosting) rather than as a platform for productivity-enhancing digital transformation.

These trends are reflected in industry composition. In the U.S., high-IT-spending industries—banking, finance, and business services — drive enterprise cloud adoption. In China, however, the economy is dominated by low-IT-spending sectors such as manufacturing and construction. These firms see little reason to invest in cloud-based enterprise software, further slowing adoption.

China’s cloud firms also lack two critical supply-side advantages. First, China has a weak enterprise software ecosystem. Because cloud revenue ultimately comes from other businesses, enterprise software is critical as it acts as a stepping stone for customers to adopt the cloud. Take Apache Spark, an analytics engine for big data and machine learning. While Spark itself is open-sourced and thus free to use, its widespread enterprise adoption in the U.S. has been driven by companies like Databricks, which help customers adopt the technology and even provide a "managed" version of the open-source software. And for customers that use Spark, moving to the cloud becomes a no-brainer, especially because Databricks has deep partnerships with Microsoft Azure and Amazon Web Services that make the transition to using Spark in the cloud seamless. In this way, companies like Databricks act as on-ramps to the cloud, helping businesses migrate workloads efficiently.

China lacks such a software ecosystem. As a result, Chinese firms not only have fewer incentives to migrate to the cloud but, when they do, they are more likely to use it for basic, low-margin IaaS rather than the higher-value PaaS offerings that drive profitability for U.S. cloud providers.

Second, China lacks professional IT service providers that guide enterprises through cloud adoption. In the U.S., a vast network of professional consulting firms — such as Accenture and Deloitte — plays a key role in guiding enterprises through this transition. These firms not only assist in moving IT infrastructure to the cloud but also ensure secure implementation and encourage the adoption of cloud-based software in daily operations. Acting as intermediaries between cloud providers and enterprise clients, they help streamline cloud adoption and drive demand for higher-value cloud services. In China, however, such professional services hardly exist, leaving businesses with fewer resources to navigate the complexities of cloud migration.

A Low-Value-Added Trap?

Recognizing these challenges, the Chinese government has stepped in. Since 2011, policymakers have allocated billions in subsidies to strengthen domestic cloud providers. The most ambitious initiative is “Eastern Data, Western Computing,” launched in 2020 to relocate energy-intensive computing tasks (such as AI model training) to China’s energy-rich western provinces while keeping latency-sensitive workloads (like AI inferencing) closer to users in eastern coastal cities.

This national-scale effort to coordinate cloud infrastructure with the country's energy capacity is no small task. To a large extent, what makes this coordination possible is the fact that China’s cloud ecosystem isn’t comprised solely of publicly traded private firms. Instead, the presence of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as China Telecom, China Mobile, and China Unicom allows the government to direct investment into infrastructure projects, even when short-term profitability is uncertain.

Beyond offering more flexibility in coordinating national-scale industrial policy, SOEs in China’s cloud sector encourage greater emphasis on low-margin IaaS over higher-value PaaS. While U.S. cloud providers have successfully moved up the value chain into PaaS, China’s cloud sector remains disproportionately reliant on basic infrastructure services, limiting its profitability and ability to compete globally.

Part of the reason is because China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom are hardware-first enterprises with deep expertise in telecommunications infrastructure but limited experience in developing software-based cloud services. Their focus remains on expanding data center capacity rather than building out cloud-native software ecosystems. At the same time, IaaS — particularly compute infrastructure — is seen as a strategic resource, only one level removed from energy itself, leading the state to prioritize expanding capacity rather than fostering a robust software ecosystem. Just as control over energy production ensures industrial stability, control over compute capacity secures technological self-sufficiency and resilience in an era where data processing and AI development are becoming critical economic and geopolitical battlegrounds.

This leaves PaaS development primarily in the hands of commercially oriented firms like Alibaba and Tencent. However, these efforts have been punished as both the state and market has favored IaaS over PaaS. The result is a cloud ecosystem that is highly capable of providing cheap computing power but struggles to offer the advanced services that drive higher profitability and deeper enterprise adoption.

This is exacerbated by a fierce price war among China’s cloud firms over the past two years. In 2023, Alibaba launched the largest price cuts in its history, slashing core product prices by 15% to 50%. Within a month, Tencent, JD.com, China Mobile, and China Telecom followed suit with their own reductions. In 2024, Alibaba slashed prices again, prompting another round of retaliatory cuts from competitors. The presence of SOEs and privately held firms in China’s cloud portfolio has intensified these price wars. Unlike publicly traded cloud firms, which are under constant shareholder pressure to generate returns, SOEs benefit from state-backed patient financing, allowing them to sustain deeper price cuts for longer periods without the same risks faced by profit-driven private firms.

In Sum

China’s cloud industry is at a crossroads. On one hand, state intervention and expanding infrastructure could help China narrow the gap with the U.S. On the other hand, persistent price wars and an overreliance on IaaS — coupled with weak PaaS development—risk locking China’s cloud sector into a low-margin commodity industry. On top of that, China’s underdeveloped PaaS offerings will make it even harder for its cloud providers to compete on a global scale.

To the Chinese state, however, this may very well not be the goal. Data — and by extension, compute—are seen as critical factors of production, akin to land and labor, making the cloud too strategic to be left entirely to the private sector. If this remains the case, China’s cloud sector will remain structurally distinct from its U.S. counterpart — more state-directed, possibly less profitable, but ultimately aligned with national priorities rather than besting the U.S.

See Jonathan Woetzel et al., “China’s Digital Transformation: The Internet’s Impact on Productivity and Growth” (McKinsey Global Institute, July 2014).

Nice. An under discussed side of the US China AI race. Much of the Chinese economy (at least enterprise side) doesn’t feel primed to adopt it.

Great dive.