The Rise and Fall of LGFVs

How China’s local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) became China’s most complex economic challenge

We don’t do a ton of econ coverage on ChinaTalk, but had to make an exception for this truly epic piece of independent research by Jon Sine on LGFVs. He writes the Cogitations substack.

In this essay we will tell the story of China’s LGFVs: that special type of state-owned enterprise (SOE) behind China’s infrastructure building bonanza. Along the way, we will look at the political and economic processes in China that facilitated their rise, and assess what we know and what we don’t know about them.

Data Before Narratives: The Lay of the LGFV Land

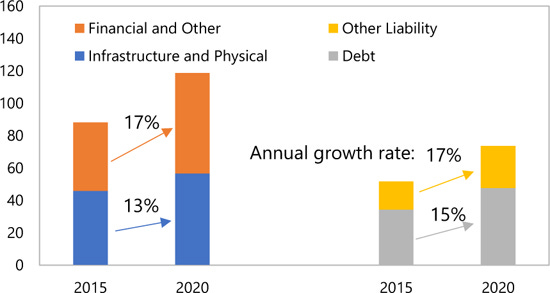

Let us begin with data. Today, there are nearly 12,000 LGFVs in China, 3,000 of which publicly disclose financials.1 Collectively, they are gargantuan. As of 2020, according to bottom-up surveys of LGFV financials, aggregated assets and liabilities equal 120% and 75% of China’s GDP, respectively.

LGFV Assets and Liabilities

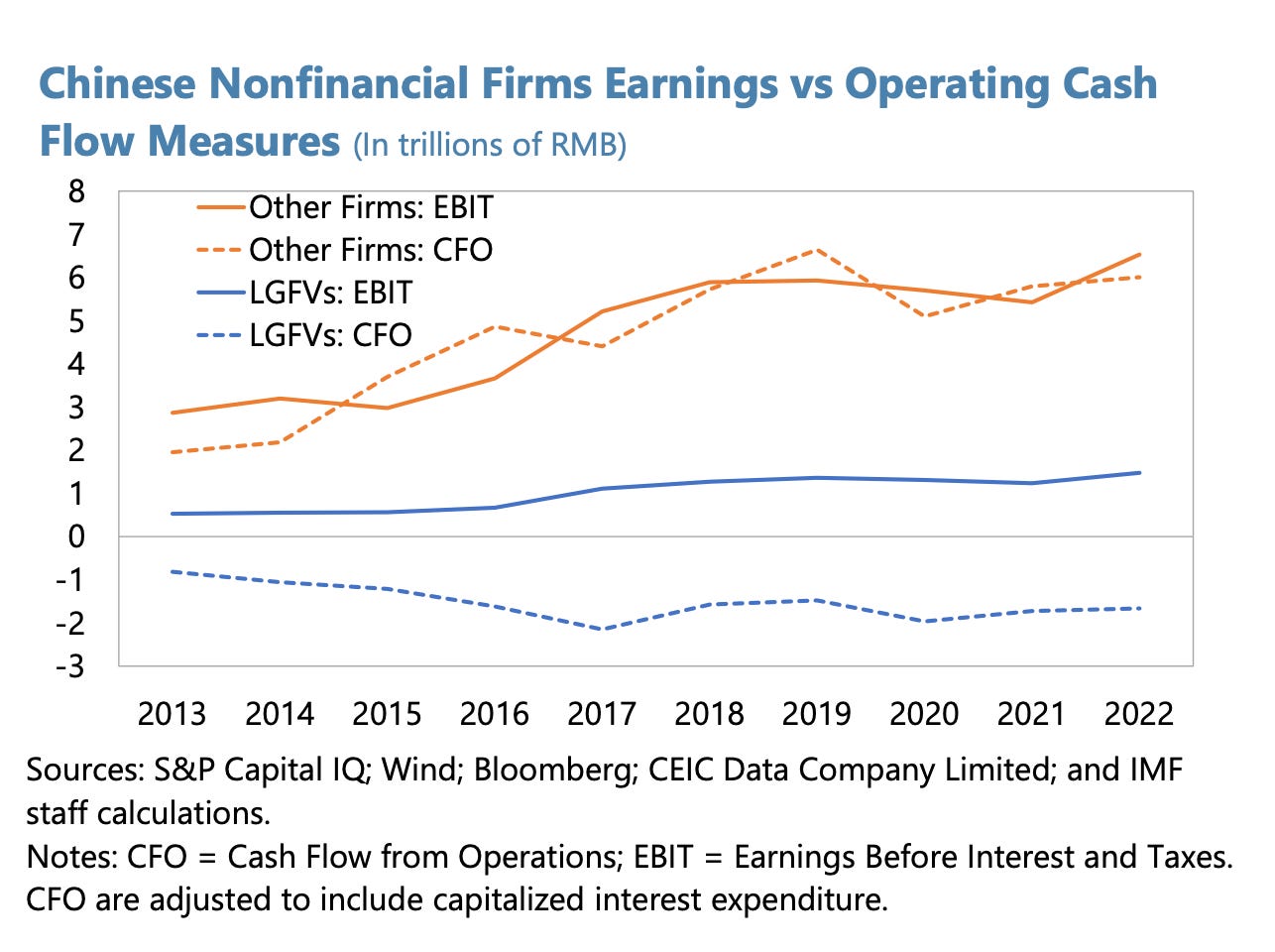

LGFV’s financial situation is, to put it frankly, very bad. In aggregate, earnings (before interest, taxes, and depreciation, i.e., EBITDA) do not cover even their interest payments. Including government subsidies only occasionally pushes the interest coverage ratio above one. Moreover, the average borrowing cost for LGFVs, 5% or so, far outpaces their 1% return on assets, posing obvious sustainability problems. 2

Interest Coverage (LHS) and Borrowing Rates (RHS)

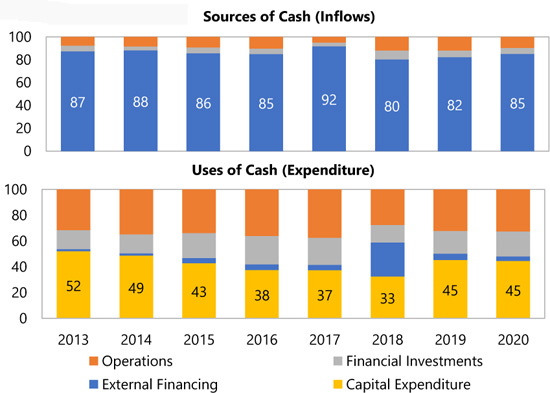

Cash flows paint an equally troubling portrait. Every year 80 to 90 percent of LGFV spending is funded by new debt. On the whole, LGFVs operating inflows do not come close to covering operating expenses. New debt is routinely added simply to make up the gap and sustain current operations.3

LGFVs Cash Flows

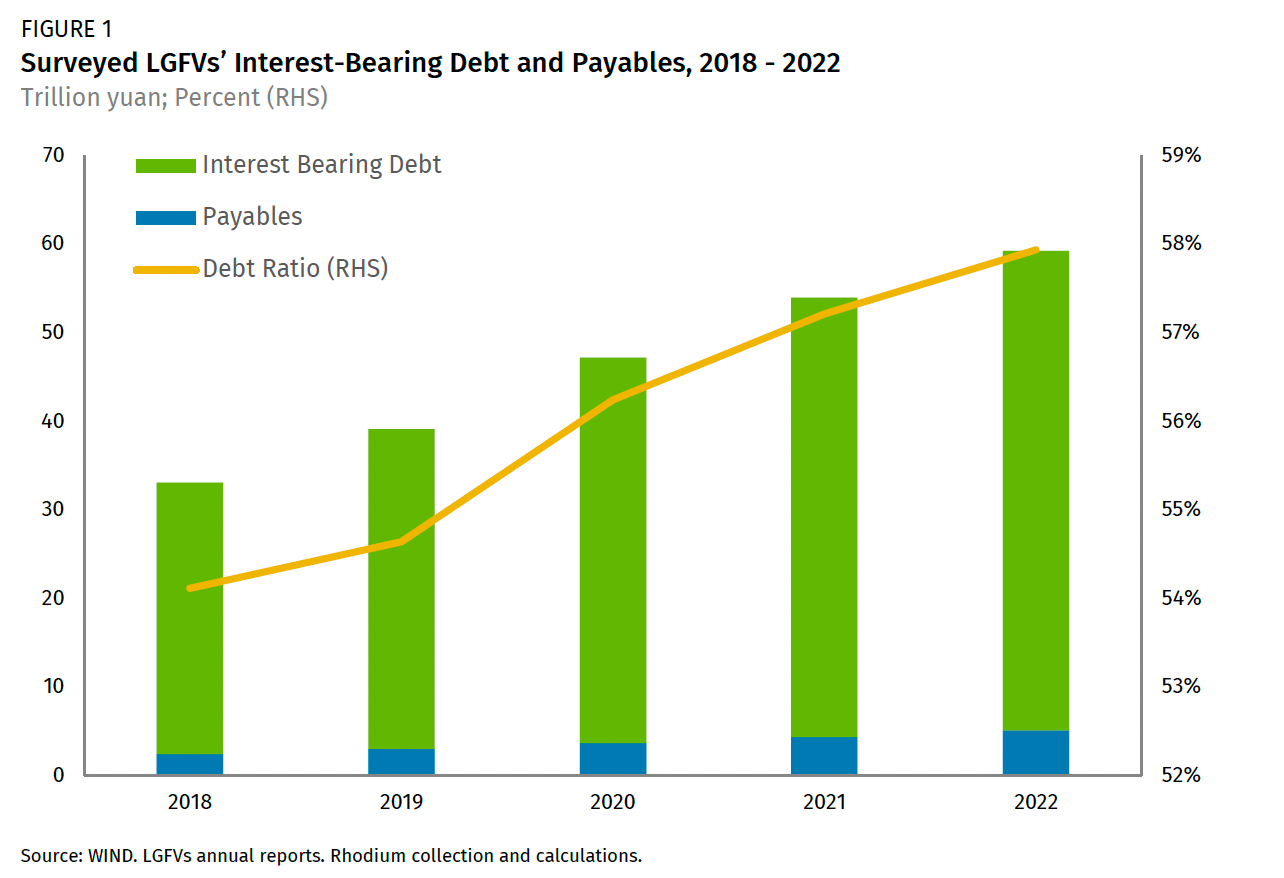

As is predictable from the above financials, the stock of interest-bearing LGFV debt has just about unceasingly expanded.4According to statistics from the IMF, LGFV’s interest-bearing debt has grown from 13% of GDP, or RMB 8.7 trillion, in 2014 to 48% of GDP, or RMB 60.4 trillion, in 2023.5

China’s Interest-Bearing LGFV Debt

LGFV interest-bearing debt is even larger than the IMF data above suggests. An unavoidable limitation of assessing LGFVs via bottom up data, as all of the above sources do, is that it only captures the 2-3,000 LGFVs that have issued bonds and published associated financials. Another 9-10,000 smaller LGFVs have never accessed the bond market and are therefore simply missing from the data.6 A simple way of trying to estimate the rest of the interest-bearing LGFV debt is to assume LGFVs follow a Pareto distribution.7 Doing so suggests IMF estimates probably understate debt by 25%. A more reasonable, if still likely conservative, estimate of interest bearing LGFV debt is probably 60% of GDP, or RMB 75 trillion, in 2023.8

Things Data Can’t Say

While the data tells a story of its own, there is also much it cannot tell us about LGFVs.9 Staring at data and getting proscriptive according to normative neo-classical doctrine risks turning us into IYIs.10 Understanding how we got here and the likely path forward requires other inputs.

What happens if we bring in the complexities of political economy? The incentives of organizational and social systems? The complexities of the past may shed light on the road ahead.

A Single LGFV Can Start a Prairie Fire

The protagonist of our story was born in a little known city in central Anhui province called Wuhu. The city, situated on the bank of the Yangtze, is just three hours south from another little known place with an important legacy: Anhui’s Xiaogang county, the place credited with pioneering China’s household responsibility system in 1978. Twenty years later, Wuhu would join its Anhui brethren in pioneering another defining feature of “socialism with Chinese characteristics”: the LGFV.11

If the household responsibility system unleashed market forces into China’s economy, then the LGFV brought the state surging back in—something Party-state leaders would likely have been keen on following destabilizing bouts of inflation in the late 80s and early 90s.12 But the direct desires of leadership were not the proximate cause for this novel feature of socialism with Chinese characteristics.

The LGFV, as we will see below, rather arose as an indirect result of three conjoined and systemic issues: fiscal centralization and decentralized local developmentalism, the Party-state’s organizational and incentive system, and the weakly institutionalized nature of China’s political system.

A spark only starts a fire in a flammable environment.

The Confederated States of China

In 1781, the United States was governed under the Articles of Confederation. That system had a glaring flaw: an utter lack of centralized fiscal revenue, which neutered central governance capacity. Within eight years a constitutional convention was called to forge a new system, which I would argue turned out better.

When China began allowing markets after Mao, the economic structure shifted beneath Beijing’s feet. SOEs crumbled, the tax base eroded, and tax evasion increased. Total government revenue and the center’s revenue share massively declined.13 Though one imagines the Soviet Union’s recent dissolution was top of mind, one could have also seen parallels between Beijing’s situation in the early 1990s and America under the Articles of Confederation.

The Partial Red-Herring of Beijing’s Fiscal Re-Centralization

In the early 1990s Beijing sought to re-affirm central authority. One of the more reliable ways to do so is to take control of the purse. Of this view were General Secretary Jiang Zemin and his Premier Zhu Rongji, who pushed forward a major fiscal and tax restructuring in 1994. Two big changes were wrought. First, Beijing decisively centralized revenues while keeping expenditures decentralized. Second, Beijing barred local governments from running deficits, and from borrowing.14 China, the most fiscally decentralized country in the world in terms of local expenditure share, overnight developed a stark vertical fiscal imbalance, with unfunded mandates at the local level.15 Nearly an inversion of the original problem. But Beijing was happy and that’s what mattered (to Beijing).

Ultimately, Beijing wanted revenues routed through its own coffers for purposes of control, most importantly over subordinate levels of government, and redistribution. That becomes evident once you realize the central government simply transfers back just about all the money. Indeed, once transfers are accounted for the oft-cited central-local fiscal gap disappears.16Unfunded mandates did materialize following the 1994 budget reform, but in a more nuanced way.

The problem was (and still is) in the nature of the intergovernmental transfer system. Beijing bureaucrats apportion funds to the provinces, who are in charge of apportioning funds to prefectural cities, who are in charge of apportioning among county level units, who are in charge of apportioning among townships.17 But sometimes the provinces send funds directly to the counties, by passing the cities. Each level also needs their own funds. And each level can take months before passing on the funds it received. By the time funds get from top to bottom, a year or more can pass.18

An Example of Intergovernmental Transfers

It’s fairly easy to understand how funds may also leak, be misappropriated, or miss their mark. The severity of funding problems ends up being highly geographically variable. The resource gap for many local governments is real, if overstated at the macro-level if transfers are not considered.

When we talk about China’s fiscal revenue, what is likely more important to understanding the evolution of China’s political and economic trajectory is the production bias baked into the system: 60% of taxes are on goods and services, just 6.5% on income.19

Share of major taxes in total tax revenue

Local government’s fiscal structure highly incentivized them to figure out how to boost production. So they turned to the task with their highly decentralized expenditure capacity and, more importantly, decentralized powers of off-budget liability-creation.20

The Decentralized Developmental State Gets a New Tool

The expenditure portion of the government income statement is more important than revenue in understanding the rise of LGFVs.21 This owes to the pervasive and multi-faceted role of local governments in economic activity, mobilizing for development.22

Local officials in China have long competed intensively within a hierarchical system that is both decentralized and weakly institutionalized. A combination of top-down and bottom-up incentives attracting them to or diverting them from enacting the center’s ambitions. This developmental modality post-Mao evolved into what is colloquially called the “mayor economy.”23 It is in large part an institutional outgrowth from China’s decentralized Maoist-Leninist system, and arguably traces even further back to imperial-institutional legacies.24 Along with previously noted fiscal incentives, a particularly noteworthy top-down feature has been the Party’s Organization Department and its control and influence over local cadres promotion.25 Mao’s death enabled the re-direction of the Party-state’s high-powered incentive systems to a new goal of production-oriented tournament style competition.26 Arriving at a period of burgeoning hyper-globalization, localities soon began to fight tooth and nail to lure FDI.27 A period of post-Mao capital deepening, urbanization, and transition beyond agriculture occurred at unprecedented speed and scale.

Local officials hunted within this incentive ecosystem for ways to increase their economic role.28 One seemingly win-win way for local governments to deepen their involvement was infrastructure—a role that arguably became their most important.29 To fully step into this infrastructure supplying role, however, local governments needed a new financing tool. Given the enormity of the task, no typical fiscal revenue stream would suffice. That’s where a little ingenuity from financial big whigs at China Development Bank (CBD) came in to play. Chen Yuan, son of famed Chen Yun and then head of CBD, helped local officials in Anhui and Wuhu concoct a simple but brilliant way to expand their economic footprint: create a corporate entity owned by, though at arms length from, local governments that could borrow unconstrained by the 1994 budget and regulatory regime. The entity’s raison d'etre was simple: (1) raise money and (2) build infrastructure. This was the “Wuhu model,” and in 1998 it birthed China’s very first LGFV: Wuhu Construction Investment Company.30

Over the next twenty years the Wuhu spark would engulf the country.

Land, Meet Finance

Leveraging land was Wuhu Constuction Investment Company’s distinguishing characteristic. Indeed, it was land finance that made the rise of LGFVs possible.

Local governments began selling land-usage rights in the 1990s, around the same time as Wuhu’s LGFV popped into existence. Once the land auction system was approved centrally and rolled out in the early 2000s, local government sales of land-use rights exploded.31

Proportion of state-owned land transfer revenue relative to local public budget revenue

For good and for ill local governments, uniquely empowered to requisition and sell land-use rights, used all means at their disposal to get land and ready it for sale, including mass evictions of those currently occupying it.32 The sordid history of local government land theft from China’s rural populace (re-zoning the land and selling it property developers) manifested in many cases as a Georgist’s worst nightmare, with self-immolation a not infrequent form of protest in the countryside.33 CPC led land reform in the early 1950s gave peasants their land, communization in the late 50s took it back. Marketization in the 1980s let the peasants work their land again, local governments began stealing much of it away in the 1990s. Such are the ebbs and flows in China’s countryside.34

By the late 90s, the local government revenue split began to take its contemporary shape, roughly equally divided into three parts: (1) central government transfers, (2) locally generated revenue, and (3) land sales.35

Land sales and locally generated revenue are highly intertwined. In the late 1990s, local governments began selling industrially-zoned land cheaply to attract companies that they could tax harvest. Selling land low seems counterintuitive until you realize locally derived revenue mostly comes from value-added and corporate income tax. Thus local governments became ever more perfect price discriminating monopolists: they sold residentially zoned land (居住用地) high to maximize one off revenue, but sold industrially zoned land (工业用地) low to maximize recurring revenue.

LGFVs took on two very important roles in the burgeoning land finance system. First, the pivotal role of preparing land for sale. Such preparation not only involves evicting rural residents and coordinating with the local governments on compensation (or lack thereof), but also requires multiple land development steps, known as the “seven connections and one level” (七通一平). LGFVs were used to build (1) road connections, (2) water supply connections, (3) electricity connections, (4) drainage connections, (5) heating connections, (6) telecommunications connections , and (7) gas connections. They also leveled the land in preparation for development. The extensive requirements of land development meant that often local governments were losing money on the land use sale (a problem that has only gotten worse in more recent years).36

Second, to finance these land-prepping activities, LGFVs ramped up use of the Wuhu land finance model. Local governments transferred more and more land use rights to these proliferating vehicles, who would in turn go to banks for loans using the land rights as collateral. And thus the land-industrial-complex began. Re-zone land. Transfer land. Develop land. Sell land. Buy land. Collateralize land.37

One need not be a Georgist to understand the unmatched power of land. Tax revenue would never have been capable of resourcing LGFVs the way land-finance did.

LGFVs, Property Developers, and Beijing’s Banking Balloon

No story on the rise of LGFVs could be told without a discussion of property developers and China’s banking system. If LGFVs are Batman, then property developers are Robin, and the banks are Wayne Enterprises (mileage may vary with this analogy).

The Wuhu model LGFV could take land from local governments and develop it for sale, but who would buy? Well, property developers. By the early 2000s, thousands of property developers had been established, eager to participate in China’s epic-scale urbanization process. Both sides of the would-be transaction, however, needed credit—particularly prior to the heyday of pre-sales in the 2010s. The LGFV-Property Developer crime fighting duo therefore needed their Wayne Enterprises.

Banks are the cornerstone of China’s financial system and were really the only game in town capable of facilitating a burgeoning land finance system. Most know about the big banks, but the stories slightly more complicated. To get localities on board with the 1994 fiscal overhaul, Zhu Rongji made a “grand bargain” with localities: in exchange for acquiescing to fiscal centralization, localities would get the right to establish their own locally controlled banks.38 As Adam Liu, whose research focuses on this topic, puts it: what is “rarely discussed is the most vital component of Beijing’s compensation package [for the 1994 budget reform]: local governments were offered the privilege of entering the banking sector.”39 When Beijing closed the front door with its budgetary restriction on lending in 1994, it opened a window.40

One can see the results: city commercial banks and other types of locally controlled banks proliferated. In 1995 the first city commercial bank was set up, and two decades later over 130 were in existence. The loan share of the big six banks collapsed from nearly 100% in the 1980s to roughly 25% today as a result of rising competition from locally controlled banks, e.g., city commercial banks, for deposits (as well as the 12 joint stock banks). The proliferation of state-owned local banks is an overlooked but consequential feature of China’s political economy, and core to the LGFV story.41

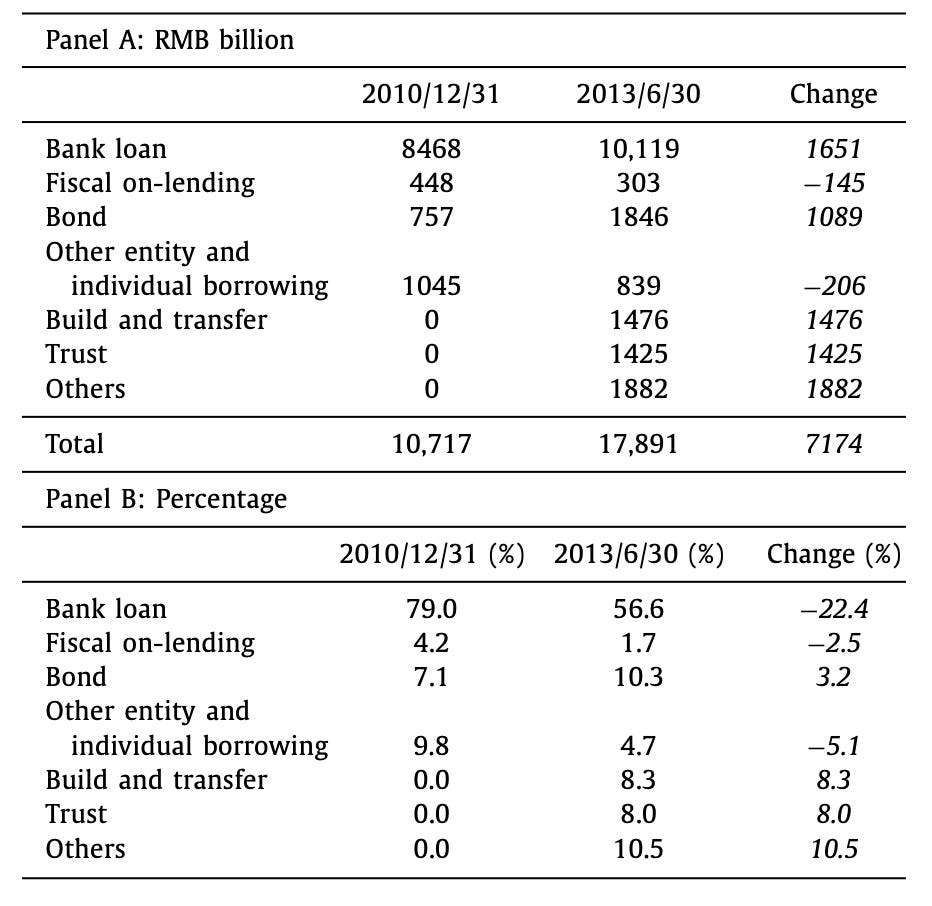

In the early 2000s banks were the primary funding source for the land finance system, on both the supply and demand side. Approximately 50-60% of real estate developers’ funding, for example, come from bank loans by 2004.42 That money, in turn, paid for land-use rights that funded local governments and, in part, their LGFVs. Meanwhile, LGFVs used their land-use holdings as collateral for loans (though in China’s weakly institutionalized system sometimes banks would lend without collateral).43 Bank loans made up about 90% of LGFV liabilities in that same period.44 China Development Bank and the big six state owned banks were core lenders, but locally controlled banks were players too, and their role would only grow more prominent.

LGFVs, property developers, and the banking system co-evolved.

Pouring Gasoline On a Fire: The 2008-10 Stimulus

Structural fiscal and developmental incentives likely would have continued to steadily drive LGFVs into ever greater positions of prominence within China’s economy.45 But it was the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 and China’s response to it that sent LGFV growth into steroidal overdrive.

No longer simply acquiescing to their use, Beijing began directing local governments to deploy LGFVs for countercyclical infrastructural stimulus and tasked the banking system with funding them.46 The People’s Bank of China explicitly called on local governments to use LGFVs to borrow, the banking regulator (CBRC) explicitly encouraged LGFV use, as did the Ministry of Finance.47 Buyer of narratives therefore beware, lest you fall victim to the woe is me central government fairy tale. This puts a bit of a lie to the notion that Beijing is effectively a responsible parent figure always trying to constrain misbehaving local officials.

When the center boldly announced its RMB 4 trillion stimulus plan to ward off recession, it did not intend to fund the stimulus directly but instead turned to local governments, now replete with bank licenses and financing vehicle. To this day we don’t know exactly how much China actually spent on its stimulus, though its clear the vast majority came off-budget via LGFVs. Only a trillion yuan shows up on the central government balance sheet.48 Beijing’s calculation of “official debt” accrual to LGFVs in 2009 and 2010 was RMB 3.6 trillion. But this number leaves out a substantial and non-transparent amount of LGFV debt.49 Some estimate LGFVs took on roughly a third of all new bank loans issued in 2009, and continued on in 2010 to account for 40 percent.50

As one example of what funds were used for, LGFVs mobilized to double-down on the build out of industrial parks and development zones. Parks and zones are used by local governments to attract companies, and thus revenue, jobs, and pad cadre evaluation, while from the central government perspective they are suppose to catalyze industrial clustering effects. From 2006 to 2018, officially recognized national and provincial level zones alone increased by 1,180, from 1,363 to 2,543.51 These numbers, large though they are, understate the extent of the build-out: they only include officially recognized zones above the city-level and do not reflect ongoing consolidation, merging, and cancellation of zones.52

One analysis of the post-2008 expansion stated that it “demonstrates that local governments are responsive to central commands.”53 Such a statement must be severely qualified. Local governments could not have been more eager to oblige Beijing in this instance, they tend only to respond with alacrity when doing so also corresponds with their interests. The host of epithets—from foot dragging, to bureaucratism, to formalism—is testament to the legion examples of local government non-compliance. But unleashing the LGFVs was also a boon for local cadres, their promotion metrics, and arguably for local development overall. It also made a fair amount of sense: local governments are closest to the ground and best understand what projects might work. And so China’s counter cyclical stimulus ran through local governments and their LGFVs.

Predictably, Beijing quickly lost what little control it had of the LGFV expansion process. Not only was the credit expansion much greater than Beijing intended, but LGFVs institutional role expanded and embedded deeper into the sinews of China’s economy. The analogy of LGFVs as Sorcerer’s apprentice is imperfect but apt.

Bend it Like Huarong

As they expanded, LGFVs moved out well beyond their initial infrastructural and land development remit. One analogy is that LGFVs have become akin to twelve thousand little Huarongs. Huarong, the country’s largest asset management company, was established just a year after the first LGFV in 1999. Colloquially referred to as a “bad bank” because it was set up to take non-performing loans off the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s balance sheet.54 Initially an asset recovery firm, Huarong metastasized into a massive conglomerate with dozens of subsidiaries involved as many different industries. The crazed expansion got so crazed under former Chairman Lai Xiaomin that the CPC decided to execute him.55 LGFVs have similarly spread out well beyond their original mission under increasingly complex corporate structures.

One categorization schema for LGFVs, offered by analyst Glenn Luk, divides LGFVs as follows: (1) The Infrastructure LGFV, (2) The Real Estate Asset Management LGFV, (3) The Structured Asset-Backed Warehousing LGFV, (4) The Financial Intermediary and Investment Holding LGFV, and (5) The Conglomerate “All-of-the-Above” LGFV. If the names don't immediately make senes to you, I invite you to read his post (see footnote).56 Suffice to say that after the 2008 explosion, NAO’s first audit in 2011 discovered that only half of LGFVs were strictly focused on government infrastructure projects, with 18% partly focused on them and a full third entirely focused on market-oriented projects.57 The issue has only exacerbated since.58

A recent Bank for International Settlement paper on the post-stimulus transformation of LGFVs shows just how far they have meandered beyond infrastructure. Between 2004 and 2018, only 20% of the investments made by the 4,432 they analyzed were into public goods sectors. They focus on Guizhou’s Dushan County as a concrete example. This LGFV operates across as many public goods sectors (e.g., electricity, heat production & supply, health, social security) as it does market sectors (e.g., software and IT services, retail, wholesale and real estate). The authors argue there is a U-shaped return to this sort of diversification, with some amount potentially helpful to growth but too much being harmful.59 Others, however, are much less sanguine, and see this expansion as potentially at the core of capital misallocation in China and the country’s overall productivity slowdown.60

LGFVs fed off a mix of moral hazard, unfettered access to credit, and indeterminant state responsibility for liabilities—that is, substantial state involvement under conditions of weak institutionalization. On their expansionary march LGFVs, from a more macro perspective, have cultivated an impressive web of investment linkages:

Red LGFV Over China: The Case of Zunyi Road and Bridge

Zunyi, a small city located in China’s southwestern province of Guizhou, does not often make the news. The city’s claim to fame dates back to the Long March in 1935, when it played host to a meeting that, according to Chinese Communist Party (CPC) lore, decisively established Mao Zedong’s leadership over the Party. Other than that, Zunyi is relatively unremarkable, a city of middling population and economic development, firmly in the 3rd tier of China’s unofficial city ranking system. One recent development, however, has once again brought attention to the city: the increasingly urgent Party-state effort to deal with LGFV debt. Zunyi Road and Bridge Construction (遵义道桥建设) is the star of the show. A snapshot of Zunyi’s corporate structure offers hints at some of the poblems.61

Zunyi Road and Bridge, like most LGFVs, is fully-owned by the local, in this case city-level, State Asset Supervision and Administrative Commission (SASAC).62 Established in 1993 and with registered capital of RMB3.6 billion, it is the second largest of of Zunyi SASAC’s 40+ holdings, many of which also appear to be LGFVs. Zunyi Road and Bridge is itself a holding company with at least 10 companies under its umbrella. Many of these firms are also LGFVs. Its largest holdings include: Zunyi Daoqiao Agricultural Expo Park Co., Ltd., Zunyi Daoqiao Hotel Management Co., Ltd., Zunyi New District Construction Investment Group Co., Ltd., and Zheng'an County Urban and Rural Construction Investment Co., Ltd.

Zunyi Road and Bridge Holdings

Road and Bridge’s subsidiaries also have subsidiaries. Take for example, its largest subsidiary: Zunyi City Baozhou District Urban Construction and Investment (遵义市播州区城市建设投资经营), with registered capital of RMB 1.6 billion. Baozhou Urban Construction itself fully-owns a diverse array of 10+ businesses, ranging from a funeral service company, to a financial leasing company seemingly focused on industrial equipment, to a water services management company, as well as a 49% stake in a property management company and a 5% stake in another diversified LGFV holding company.

Holdings of Road and Bridge Largest Subdiariy, Baozhou Urban Construction

The financing practices to go along with such a web of holdings have been similarly convoluted. One company may acquire loans or go to the bond market only to on-lend to its affiliated entities. There are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of LGFVs like Zunyi Road and Bridge and like the one in Dashan County mentioned earlier. These conglomerate LGFVs undertake what economist David Daokui Li describes as a “nested layering approach” to levergae. Companies at one level borrow funds, use that borrowed capital to secure additional loans at the next subsidiary level, and amplify debt layer by layer.63 All the while moving into more and more lines of business.

Evolving Liabilities: Bonds and Shadow Finance

Beginning almost immediately after their massive GFC-era expansion, Beijing turned from hot to cold on LGFVs. The center unleashed the National Audit Office (NAO) twice upon localities to try and scrape together the extent of the LGFV bonanza, first in 2011 and then again in 2013.64 The then bank regulator, CBRC (which then became the CBIRC and, as of 2023, the NFRA) also began keeping a comprehensive list of all LGFVs around that time, dividing them into “good” and “bad” and ostensibly demanding banks refrain from many types of lending to those on the naughty list.65

Constraints on bank lending, combined with the need to rollover short-term (~4 year) loans post-08, created huge incentives for LGFVs, local officials, and many other actors to devise alternative financing methods for these increasingly systemically important vehicles.66 A cat and mouse game had begun between Beijing regulators and localities.

LGFVs and China’s financial system proceeded to co-evolve.67 As LGFVs moved beyond plain vanilla bank loans, they played a huge part in spurring two other major financing channels: municipal corporate bonds and shadow banking.

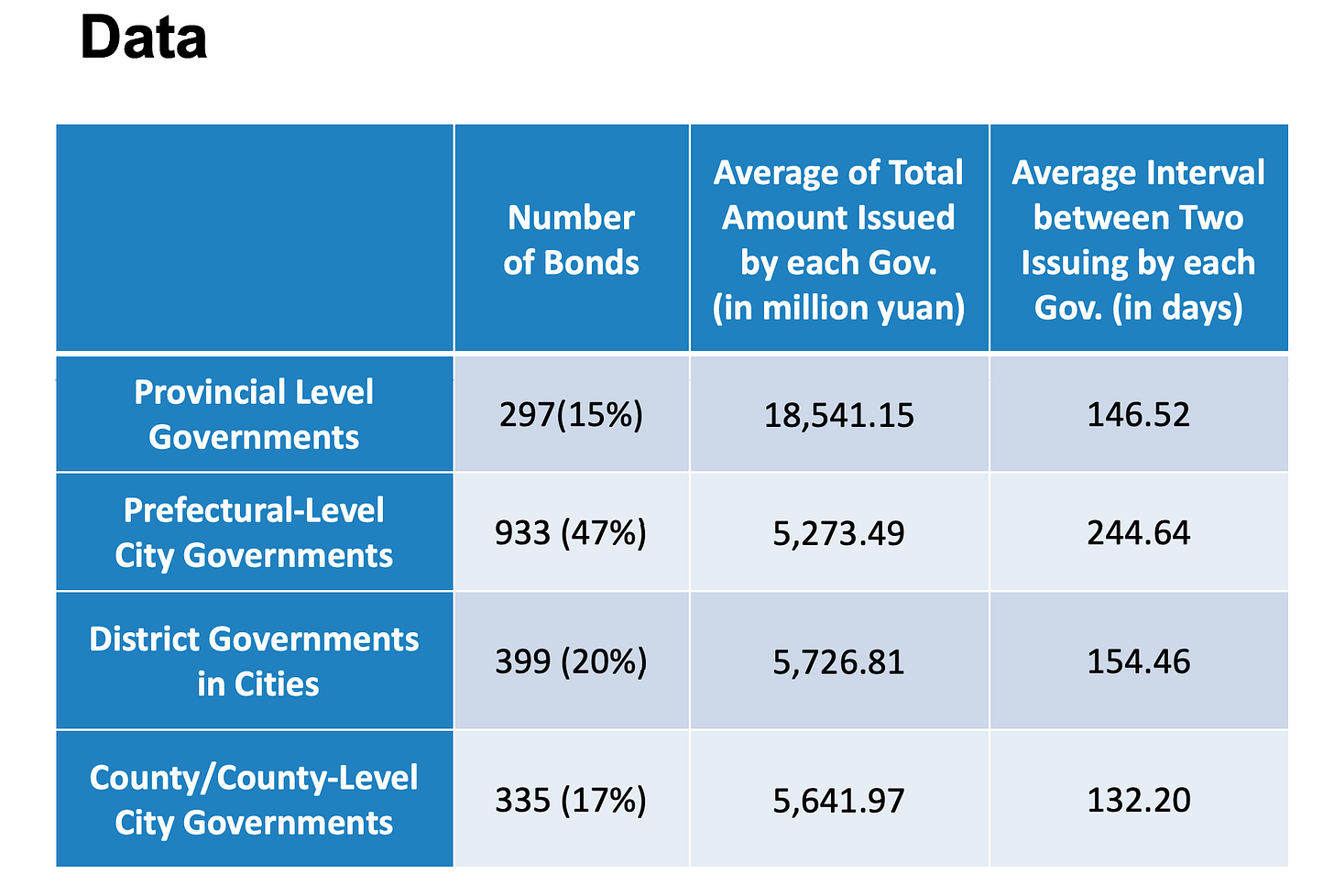

Municipal Corporate Bonds

Municipal corporate bonds (MCBs) are bonds specifically issued by LGFVs (they are sometimes called chengtou). One informed analysis of them wryly describes them as the quintessence of socialism with Chinese characteristics: “MCBs are a perfect example of how planning and the market mix in the contemporary Chinese economy: They are implicitly backed by local government (hence “municipal”), but legally speaking they are issued by LGFV entities just like other regular corporations (hence “corporate”).”68

In 2006 only 17 LGFVs had issued a bond. By 2010 it was 1200. By 2013, 1700.69

The rapid growth owes to the central government’s stimulus-era decision to allow and encourage LGFVs to begin issuing bonds (enterprise bonds, a subset of corporate bonds, which at the time were regulated by NDRC, but as of 2023 are now regulated by CSRC).70 Data compiled by Fitch cuts a striking image:

The municipal corporate bond market really exploded in size, though, as 1-to-2 year short-term bank loans to LGFVs needed to be rolled over and re-financed.71 While the stimulus was the spark, the real acceleration came when it was time to rollover short-term debt.72 One study combed through bond prospectus of MCB issuers and disaggregated issuance according to stated purpose (prospectuses require issuers to state the purpose for the funds). The data clearly indicate a rapid rise beginning in 2013, precisely when the average short-term bank loan would have been coming due.73

Municipal corporate bond (MCB) Issuance by Purpose (2004-2016)

Rather than close, most “bond buyers preferred LGFV bonds because they offered higher yields than corporate debt, but were considered government guaranteed, even though they funded projects that typically had no capacity to repay the debt.”74

Most significant to the story, though, is who bought the bonds and how.

Shadow Finance: The Banks Shadow

Shadow banking is financial activity outside regulated channels. But in China, shadow banking takes on a double entendre of literally being the shadow side of banks. China’s shadow banking mirrors the rest of the financial system in being massively bank dominated. LGFV municipal corporate bond issuance was, as it turns out, mostly bought up by banks via shadow banking products.

Wealth Management Products (WMPs), or special funds set up to skirt regulations on deposit rates, are the most important shadow banking product. WMPs invested heavily in municipal corporate bonds. Chen and He et al calculate that 62% of all MCB proceeds came from WMPs. And it was banks that created those WMPs, of course with money that ultimately belongs to household depositors/lenders.75 Shadow banking and WMPs, much like MCBs, may not have precisely arose via LGFV stimulus, but massive pressure to rollover debt and refinance short-term stimulus loans created an extreme accelerant.76

Systemic incentives aligned to shift a substantial share of banking into the shade. Banks already engaged in regulatory arbitrage to get around the deposit rate ceiling and intermediate funds they otherwise wouldn’t have been able to.77 LGFVs got funds they wouldn’t have otherwise had access to. And households got higher returns via WMPs, which they viewed as fail-safe investments (owing to rampant moral hazard).78 Competition among banks to issue WMPs and compete for deposits, specifically between the big four and small and medium sized banks (SMBs), also intensified, going from luring deposits via offers of cooking oil, gold bars and cash to issuing higher-interest WMPs.79 As the figure below shows, WMP issuance as a share of all bank assets takes off in 2011, precisely when LGFV rollover needs are emerging.

Entrusted loans, meanwhile, were the second most prominent category of shadow banking, making up roughly 20 percent of shadow lending relative to WMPs 52 percent.80 Entrusted loans are loans between two non-bank entities that are facilitated by banks, a service for which the bank takes a fee but no exposure. The main characterstics of entrusted loans is firms with privileged access to China’s banking system, such as SOEs and larger LGFVs, channeling capital to those with less access.81 Most such transactions occur between affiliated parties, as between parent and subsidiary, such as in the case of Zunyi. This type of lending increases when credit conditions tighten, precisely as happened when Beijing tried to limit the credit deluge following its GFC-stimulus.82 Entrusted loans, a marginal part of total social financing relative to bank loans, clearly take off with LGFV refinancing.

Post-Stimulus Rise of Entrusted Loans (2002-2020)

Beyond WMPs and entrusted loans, trust companies also came onto the scene. Trust companies are “conduits that connect financial and non-financial institutions with asset classes that their licenses would otherwise prohibit.”83 Many trusts served as yet another mechanism to intermediate bank financing, in large part to LGFVs. The quintessentially convoluted process goes something like this: a bank makes a loan then sells it to a trust, the trust packages multiple such loans into a “trust plan,” then another bank’s WMP invests in that trust plan—investment banks would later serve as an additional layer, intermediating the second bank’s WMP investment into the trust plan.84 Such is the financial cat and mouse game.

Thus, all told, MCBs and shadow banking explode together around 2012 when LGFVs needed post-stimulus refinancing. The stimulus-through-LGFVs and follow-on regulatory tightening had the incidental effect of hastening development of China’s bond and shadow banking markets. LGFVs and the financial system co-evolved.85

Growth of shadow banking in China (2010-2020)

The evolution of LGFV liabilities reflects the tale. Based on a bottom-up estimates, Zhang and Xiong estimate loans fell from 79% of LGFV liabilities to 60% by 2015. That ratio has remained roughly stable up to today. In 2023, for example, global asset manager PIMCO estimated that the composition of LGFV debt was 60% bank loans, 30% bonds, and 10% other financing sources.86 Clearly bank loans still dominate, but given the extent of resources in play, the compositional shift was pivotal.

Evolving LGFVs Liability Composition

Beijing’s effort to conjure then control LGFV borrowing contributed to a sort of diversification of the financial system, including the massive expansion of the bond market. Many called for just this sort of change to Beijing’s bank dominated financial system. It’s a bit like a simulacrum of diversification, though, as banks remained the ultimate buyers, just with additional steps. But, at least when it comes to bonds, much debt was refinanced in substantially more sustainable manner. What’s more most of the ultimate lenders, via WMPs, were rich coastal Chinese folks. A potential avenue for common prosperity, and partial resolution to LGFV debt, could be defaulting on those bonds. That, however, could also risk seismic upheaval in a system laden with moral hazard and wherein not a single LGFV bond has yet to default.

The question of how to resolve the seemingly unstoppable freight train of LGFV borrowing lingered on.

Fiscal Reform Round 2: “Solving” The LGFV Debt Problem

As with property developers, the central government has been aware of problems with LGFVs for a long time and has been moving to resolve what they call LGFV’s “hidden debt.” As mentioned, regulations were first put in place in 2010 to impede bank lending to LGFVs. But the most important effort to try and resolve LGFVs debt and financing problems came with the country’s second big change to its budget framework in 2014, precisely two decades on from the last one. This time, a core purpose of the change was to deal with off balance sheet LGFV debt.

Most pertinent to resolving the LGFV situation, local governments were given a mandate and resources to swap off-balance sheet “hidden” LGFV debt with on-balance sheet bonds. Local governments were now given a clearer path to issuing debt themselves via bonds, and being actively encouraged to do so. The goal was to recognize contingent debt, refinance it with longer duration, lower interest rate bonds, and eliminate LGFVs within three years. Beijing’s “new budget law prohibits local government and their branches from borrowing in any other form, and unless otherwise specified by law, from offering any credit guarantee to any organization or individual.” Then the State Council issued Document Number 43 in September 2014 which aimed “to make these rules explicit” by stating LGFVs did not have “the authorization to borrow on behalf of the local government. If the only business of an [LGFV] is to borrow on behalf of the government, it should be shut down.” The goal, according to economists Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song, “was to entirely eliminate [LGFVs] by replacing the debt of the [LGFVs] with local government bonds within three years.”87 If this was indeed the goal, then the reforms clearly failed.

China’s Interest-Bearing LGFV Debt

The failure has several causes. From the start, there remained debt classification issues with regard to what Beijing and local governments considered contingent liabilities. As a result, and the first big cause of the failure, is that a sizable amount of LGFV debt—equivalent to at least 13.4% of GDP, which the IMF’s 2018 Article IV derived from NAO estimates—was likely never transferred.88 Officially recognized local debt did shoot up as part of major bond swap program, and LGFV debt in turn fell from an estimated 32.1% of GDP in 2013 to 13.4% in 2014. But then LGFV debt as percent of GDP shot back to its original levels within three years.

Second, the new bond financing mechanism remained basically the same as the old one. The only difference was that Beijing actively used it. As before, all bond issuance has to be approved by the central government, via the State Council (and approved by National People’s Congress). In turn, provinces are in charge of issuing the debt and distributing the proceeds to all lower level governments. While controlling potential wanton lower-level behavior, it also creates an immense coordination problem lower levels and upper levels. Not only might upper levels not know what lower levels really need, lower levels may have incentive not to fully disclose how much they need. Low-level local governments would thus clearly find it easier to continue relying on channels they control (their banks) rather than official channels like special purpose bonds that are highly onerous, take a long time to get funds, and subject local officials to greater scrutiny.

Third and most important: nothing was changed with regard to local developmental incentives. Local officials were still highly involved in the economy, still controlled local banks and shadow institutions, and still stood to benefit in a variety of ways from credit finding its way to LGFVs. Predictably, new lending did not stop and LGFV debt continued to pile up.

Policies and Counter Policies (上有政策,下有对策)

The center’s hands have been far from clean in the LGFV clean up process. Throughout the winding road of LGFV growth the center has repeatedly stoked the LGFV fire only to then play fireman. The 2009 LGFV stimulus followed by crackdown is one example, but the same dynamic happened just prior to 2014 and again just after. In 2013 the State Council called upon local governments to increase infrastructural investment once more.89 Then, just after the big 2014 Budget Law change, “the State Council issued a new decree in May 2015 (document 40) that reversed its attempts to crack down on [LGFV] borrowing,” urging “financial institutions to continue to lend to [LGFVs].”90 Not only do local governments counter Beijing’s policies, Beijing often counters Beijing’s policies.

In more recent years, however, Beijing has gotten more focused and the drum beat of regulatory restrictions has intensified. Interestingly, though, they have also become more secretive.91 In 2018 the State Council made explicit the PRC government’s ambition to wipe out all local government hidden debt, calculated per 2017 numbers, within 5 to 10 years.92

In the ten years from 2014 to 2023, amid the LGFV diversification process we discussed earlier, local SOEs began to be classified and regulated according to three categories: competitive, functional and public welfare.93 The center is trying to rationalize the operations of LGFVs, limiting state subsidization and backstopping of those oriented toward the market while phasing out the weakest performers. In practice, the policy efficacy is dubious at best. LGFVs have mixed and matched assets not only to create conglomerates that might stand on their own feet in the market, but also as part of a cat and mouse game with regulators with the ultimate goal of keeping credit flowing and their operating capacity in tact. Conglomerates with diversified holdings (from pure public-welfare to pure market) become too big to fail for local governments. LGFV complexity and debt burdens have only grown.

Since 2018 an increasing number of regulatory documents have ceased to be made public. Some speculate there is fear and hesitation within China’s bureaucracy of taking ownership over this massive problem. Amid increasing clamor to better address the LGFV issue, the PRC government issued and circulated two guiding documents within its bureaucracy in 2023. Neither Document 37 or 47, as they are shorthanded, have been made public. But substantial information has leaked within China, and discussion on WeChat is ample.

One organization, an asset management and consulting company that focuses on local governments and their SOEs, has put together a helpful guide on how struggling LGFVs might “transform and develop in the context of today’s debt package.” The firm, Nanjing based Zhuoyuan, suggests:“If an urban investment platform in a region has weak qualifications and declining financing capabilities” it might want to consider “injecting more high-quality assets and integrating weak platform assets.” Alternatively, it might try acquiring high-quality listed companies so as to “broaden investment and financing channels for urban investment companies.”94

A new round of audits is apparently under way to re-assess the scope of the LGFV debt situation. A number of other steps have also been announced, including $1 trillion worth of bonds to bring LGFV debt on-budget and refinance at lower rates, to be handled by provincial governments in the 12 most struggling provinces. More policies and announcements are expected. But what will their efficacy be?

Conclusion: The Most Complex Economic Problem?

Having arrived at the end of our story on the rise of LGFVs, the fall remains untold. The winds of change have been blowing. But a precipice remains elusive. Metaphorical cliffs do exist in China’s weakly institutionalized, moral hazard laden system. And Beijing has shown a willingness to push things off. Need we discuss the rapid fall of China’s property developers?95 With the land market contracting, local officials and LGFVs will be hard-pressed to keep a land-financed based LGFV system intact.

Why though, one wonders, has there been no LGFV policy equivalent of the Three Red Lines? Is it because they are more embedded in “the system”? Consider how much greater the on-balance sheet exposure to LGFVs is than to property developers.

Or maybe it’s because, despite escalating central regulatory action against them, LGFVs remain useful to Beijing in a variety of ways. Beijing, as we have seen, often counters Beijing (上有政策,上也有对策). LGFVs are handy not just as shock absorbers against economic recession, nor just as levers to buttress growth and employment, but also as vehicles for carrying out country-wide goals such as extreme poverty elimination and shanty-town revitalization. But the costs of using LGFVs mounts.96

Whether or not shock therapy comes for LGFVs, the incentive ecosystem is shifting. Beijing has decided its bureaucracy must mobilize not principally to rectify backwards productive forces, but rather to remedy the “contradiction between people’s ever-growing need for a better life and China’s unbalanced and inadequate development.”97 At least one implication is clear: the land-finance system that for the last two decades has been the lynchpin for much of China’s development is being directed toward the dustbin of history. High-powered top-down incentives to boost growth are no longer so high-powered. Property developers have taken their hit, but LGFVs remain at large.

Ambiguous mandates render the future of LGFVs difficult to divine. What constitutes a better life, precisely? Growth is still important, but must be balanced with security and needs to be “high-quality.”98 Local experimentation is still encouraged, even demanded, but must comport with stricter top-down preferences.

Despite the diversification we have seen in the holding schemes, asset structures, and liability composition of LGFVs, there remains a lack of diversification where it matters. Local Party-state officials continue to control LGFVs and the local banks, and possess immense influence over many other facets of their local economy. In a remarkably concise passage from his book 置身事内, Lan Xiaohuan argues that “the root cause of the government’s debt problem,” and by extension of low-quality growth, “is not insufficient revenue, but rather excessive spending, as the government has taken on too many roles in developing the economy. Therefore, the debt problem is not simply a ‘soft budget constraint’ issue or a problem solved by modifying the government’s budget framework. Instead, it is fundamentally a problem of the government’s role.”99 LGFVs are the crux of this problem. And it is why property developers, most of which were private companies, have not posed nearly as vexatious a problem for Beijing.

A decade ago Beijing not only set out to constrain LGFVs, but to eliminate them. Fiscal restructuring proved insufficient. Today, localities still have dauntingly expansive roles and mandates, will new sources of financing materialize or will they be forced to abdicate? In this evolving context, will local officials face new incentives to keep their all-purpose handy man, the LGFV, alive and kicking? Will LGFVs whither away, as Lenin once promised the Soviet state would? Who will make them? With a new round of audits sweeping the nation alongside top-down inspection tours and the ongoing anti-corruption campaign, what might become of China’s 12,000 LGFVs?

A common saying in the Party these days holds that it is sometimes necessary to “turn the knife inward and scrape poison off the bone.” A fundamental solution to the LGFV problem, it seems, requires a deeper cut into the system.

References and Endnotes

The 12,000 number is derived from China’s own statistics. China’s banking regulator has, since 2010, attempted to compile a comprehensive list of China LGFVs. In 2021, the CBIRC (now the NFRA) counted 11,736 LGFVs, seemingly unchanged from 2018 total of 11,734. But LGFVs can be very mysterious entities. They do not follow a specific naming system, though they normally include something about urban construction (ergo their typical Chinese acronym, urban investment company, or chengtou [城投]). They are all local, state-owned enterprises. With the center using this list to, in large part, try to constrain lending to many of these entities, LGFVs and their local governments would clearly have some incentive to limit transparency, likely contributing to undercounting.

Logan Wright and Allen Feng, Tapped Out, Rhodium Group, June 2023, https://rhg.com/research/tapped-out/.

Multiple organizations exploit the spec of transparency offered by bond-issuances to estimate the LGFV debt problem. Estimates differ seemingly based on how many bond-issuing LGFVs get included in their bottom-up estimates.

At the upper bound of comparables, Rhodium Group, collated and analyzed annual reports from 2,892 LGFVs that have issued bonds.

A 2022 study by the IMF, presumably using very similar methodology as the Article IV consultations, used CapitalIQ’s more limited database to analyze 2200 such LGFVs. PIMCO used Wind Financial and perhaps some proprietary information to come up with its own bottom-up estimate of LGFV and other government debt.

Nearly every year IMF Article IV report on China changes its estimate of LGFV debt levels. For instance, these are the estimates of China’s 2017 LGFV debt:

2018 Article IV: 24.1%

2019 Article IV: 24.1%

2020 Article IV: 32.0%

2021 Article IV: 32.2%

2022 Article IV: 37%

This is annoying though understandable given limited transparency and a changing pool of LGFVs with financial disclosures. Part of the explanation, at least for the big change in 2020, is a methodology in that yea: “IMF has historically used a top-down approach to estimate China’s LGFV debt based on the results of the National Audit Office (NAO)’s 2013 audit of LGFV debt. Beginning in 2020, the IMF switched to a bottom-up approach based on the firm-level financial statements of bond issuers classified as LGFVs by the bond market regulatory agency NAFMII, in line with observed market practice.” https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/002/2022/022/article-A003-en.xml

Another possible explanation is offered in Chen (2020): “WIND classifies MCBs following the ChinaBond Pricing Center. As a subsidiary wholly owned by China Central Depository & Clearing Co., Ltd., ChinaBond provides authoritative pricing benchmarks of Chinese bond markets. Whenever ChinaBond changes its MCB component list, WIND adjusts its classification retroactively, causing the number of MCBs in our study to potentially differ from other studies on MCBs.” See: Chen, Z., He, Z., & Liu, C., “The financing of local government in China: Stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes,” Journal of Financial Economics, 2020, page 48.

The only data sources that include LGFVs beyond those issuing bonds are China’s official audits, conduced in 2011 and 2013, by the National Audit Office (NAO). See: National Audit Office, “2013 Announcement 32: Nation-wide governmental debt audit results,” (2013年第32号公告:全国政府性债务审计结果), 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20140104011301/http://www.audit.gov.cn/n1992130/n1992150/n1992500/n3432077.files/n3432112.pdf

We have no more recent bottom-up estimates of the entire galaxy of LGFVs. Prior to 2020, the IMF appears to have simply projected forward those estimates.

Those data, however, are limited. As Bai et al (2016) describe: “the data on the Audit Office only covers "official" debt of the LGVs, which the Audit Office defines as "the debt that government has responsibility to repay or the debt to which the government would fulfill the responsibility of guarantee or for bailout when the debtor encounters difficulty in repayment.”” Thus Party-state data may tell us how much LGFV debt was used on infrastructure, but it does not give us the whole picture. As Bai et el (2016) note, the total debt in their smaller sample of bond issuing LGFVs is larger than the total given by the NAO See: Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song, “The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion,” Becker Friedman Institute, November 2016, page 11.

Here is an overview of the data accumulated in the NAO audits:

LGFVs accounted for in the data, 2-3000, are equivalent to roughly 20% of all 12,000 LGFVs. They are highly likely to be the largest. If we assume these 20% account for 80% of interest-bearing debt, then most bottom-up debt estimates leave out roughly 20%. Thus to get a total estimate we simply multiply the original estimate by 1.25. I.e. IMF-Estimate x (1/0.8).

This is still probably an underestimate. Relative to Rhodium’s survey of 2,982, the IMF appears to include only 2,200. If we apply the same pareto assumption to Rhodium’s 2022 estimate of LGFV debt of 59% (which also includes accounts payable), we would expect LGFV debt to be approaching 75% of GDP, or RMB 90 trillion, as of 2022.

David Daokui Li’s methodology arrives at the conclusion that local debt is likely 50% higher than IMF estimates, which would be roughly equivalent to the augmented Rhodium estimate above of 75% of GDP.

If we analyze LGFVs strictly in a financial sense, we miss a major part of the picture. Namely, the divergence between economic and financial returns. Many LGFVs invest in infrastructure projects with positive economic externalities but low financial returns, precisely the kind of investments private investors would not be willing to make and wherein market failures, in the neo-classical bent, are admitted to exist. A narrow financial assessment of LGFVs would therefore fail to capture potential positive social and economic externalities.

In addition, the above data should not necessarily give cause for concern over an acute crisis. LGFVs have an abundance of real assets that could provide some amount of income. In addition, some of those assets could be liquidated to pay down some of the debt. With an asset to liability ratio of nearly two-to-one (i.e., 125% to 70%), there’s substantial buffer. And most important, not only is nearly all LGFV debt held internally but most of the lenders are also state-owned. Counter-party risk is minimal.

Intellectual Yet Idiot, coined by Nassim Taleb. “Typically, the IYI get the first order logic right, but not second-order (or higher) effects making him totally incompetent in complex domains.” Some of his other examples of IYIs in his chapter from Skin In The Game are themselves quite dumb, but the acronym is still great. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, “The Intellectual Yet Idiot,” Medium, 2016, https://medium.com/incerto/the-intellectual-yet-idiot-13211e2d0577.

Others argue that the first LGFV was developed in Shanghai six years prior. For example, Andrew Collier in his book Shadow Banking in China, states: “The first of these companies was established in Shanghai in 1992. Called the General Corporation of Shanghai Municipal General Corporation, it was set up to coordinate construction of municipal infrastructure projects, including water, sewage, roads, and other utilities. It received both municipal funds and the authority to borrow from banks…” Andrew Collier, ShadowBanking in China, page 54.

However, as Sanderson and Forsythe note, and as discussed later in this essay, the Shanghai financing vehicle did not exploit the core characteristic that distinguished the Wuhu model LGFV: land-finance. Therefore I go with Wuhu as the first LGFV. But one could reasonably disagree. Lan Xiaohuan also refers to the Wuhu LGFV as the first in his book 置身事内.

Inflation was 18% in 1988 and 1989, and after calming spiked back to 24.1% in 1994:

The high inflation of this period was perceived as a major problem among China’s leadership, considered one of Zhao Ziyang’s failings, and even a root cause of Tiananmen protests. See Julian Gerwirtz, “Never Turn Back,” Harvard University Press, 2022, pages 212, 214, 281.

In 1978, general revenue was 30.8% of GDP (with extra-budgetary contributing an additional 8%). By 1993, general revenue had fallen to just 13% of GDP. Of that, the central governments’ share had fallen to just over 20%. Shuanglin Lin, “The Fall and Rise of Government Revenue,” In: China’s Public Finance: Reforms, Challenges, and Options. Cambridge University Press; 2022, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/chinas-public-finance/fall-and-rise-of-government-revenue/D88A32934133E189C34D89C3071FCCF0.

Technically, local governments could still borrow but only if the central government expressly allowed it. In practice, they were almost never allowed to borrow. That would have change during the 2014/15 fiscal reform, which kept the same system but better defined the pathway for local government on-book borrowing and began approving more of it. For clarity on this point see: Donald C. Clarke, “The Law of China's Local Government Debt Crisis: Local Government Financing Vehicles and Their Bonds,” George Washington University Law School, https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2472&context=faculty_publications.

For more depth on the 1994 fiscal reform, see: Philippe Wingender, “Intergovernmental Fiscal Reform in China,” IMF Working Paper, 2018; Wang, Shaoguang. “China’s 1994 Fiscal Reform: An Initial Assessment.” Asian Survey, 1997, https://doi.org/10.2307/2645698

On China’s broader fiscal system, this is one of the best overviews I’ve read: Baoyun Qiao, Xiaoqin Fan, Hanif Rahemtulla, Hans van Rijn, and Lina Li, “Critical Issues for Fiscal Reform in the People’s Republilc of China,” ADB, June 2023, https://www.adb.org/publications/fiscal-reform-prc-fiscal-relations-debt-management.

Philippe Wingender, “Intergovernmental Fiscal Reform in China,” IMF Working Paper, 2018, page 6.

Most analysts, however, simply note the overall fiscal imbalance. For example: “Inter-governmental fiscal imbalances are at the root of this increase as local governments faced persistent revenue shortfalls relative to their spending obligations.” In otherwise excellent piece: Waikei R Lam and Marialuz Moreno Badia, “Fiscal Policy and the Government Balance Sheet in China,”August 4, 2023;

See also: “CDB’s lending to local governments stems from the failure of Zhu Rongji’s 1994 reforms, which left local governments with huge spending burdens—everything from providing water to roads—but no way to raise funds apart from leasing out state land. The prohibition set on borrowing by local governments was a rule observed only in the breach, just pushing the borrowing off the budget and into the arms of the state banks.” Henry Sanderson and Michael Forsythe, “China's Superbank: Debt, Oil and Influence—How China Development Bank Is Rewriting the Rules of Finance,” Wiley, 2012, page 30.

And: Nicholas Borst, “China’s Balance Sheet Challenge,” China Leadership Monitor, 2023, https://www.prcleader.org/post/china-s-balance-sheet-challenge

On the issue of intergovernmental transfers, see: Linda Chelan Li and Zhenjie Yang, “What Causes the Local Fiscal Crisis in China: the role of intermediaries,” Journal of Contemporary China, 2014, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10670564.2014.975947; OECD, Urban Policy Reviews: China 2015, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/oecd-urban-policy-reviews-china-2015_9789264230040-en#page191

For a case study of how intergovernmental transfers work in practice see: Christine Wong and Xiao Tan, “Anatomy of intergovernmental finance for essential public health services in China,” BMC Public Health, 2022, https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-13300-y/figures/1

Personal income tax, by comparison, was 54.39% in the United States, 40.41% in Germany, and 17.25% in Russia. Also worth noting, China has no capital gains tax, estate tax, or gift tax. And most importantly: no personal property tax. For comparison, property tax was 14.78% of tax revenue in the US and 12.4% in the United Kingdom in 2019, and 11.95% in Japan in 2018. For much more see: Shuanglin Lin, “The Fall and Rise of Government Revenue,” In: China’s Public Finance: Reforms, Challenges, and Options. Cambridge University Press; 2022. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/chinas-public-finance/fall-and-rise-of-government-revenue/D88A32934133E189C34D89C3071FCCF0

Andrew Batson also sees decentralized liability creation, coupled centralized revenue, as quintessential to the system. He makes his opinion on the system rather straightforward: “A combination of centralized revenue-raising authority and decentralized liability-creating authority is the worst of both worlds, and the sooner China gets away from it the better.” See Andrew Batson, “The fiscal consequences of a unitary state,” Personal Blog, October 2023, https://andrewbatson.com/2023/10/18/the-fiscal-consequences-of-a-unitary-state/.

This is also the argument Lan Xiaohuan makes in 置身事内

Also see Tsinghua ACCEPT’s very good paper on China’s post reform and opening development, which has a good explanation of how over-eager officials getting involved in the economy and stimulating excess production, among other maladies, is at the root of the economic problem as much, if not more, than fiscal imbalances. See “Summing Up 40 Years of Economic Reform and Opening,” 改革开放四十年经济总结, 清华大学中国经济思想与实践研究院 Academic Center for Chinese Economic Practice and Thinking, December 2018, page 17, http://www.accept.tsinghua.edu.cn/_upload/article/files/7a/3c/976c22ff48cfb1860f7288f6bd05/612c2ab9-2527-4237-b28e-7ce36ee2b379.pdf;

Local government spending favors production and growth oriented infrastructure rather than service oriented public goods, clearly shown via date from 1999 to 2006: Chengri Ding, Yi Niu, Erik Lichtenberg, “Spending preferences of local officials with off-budget land revenues of Chinese cities,” China Economic Review, 2014, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1043951X1400131X

See Kristen E. Looney, “Mobilizing for Development: The Modernization of Rural East Asia,” Cornell University Press, 2020.

This is campaign style governance, or goal pursuit via systems of bureaucratic and popular mobilization. For example, in the context of rural development, “governments may employ such tactics as sending official work teams to the villages, ratcheting up propaganda, setting core tasks, designating model sites, training local activists, and rewarding the most fervent participants with prizes, media attention, and other benefits designed to foster competitive emulation.” See Looney, page 6.

China’s intensely decentralized implementation system, its Leninist institutional heritage, and its extensive experience with campaigns made mobilizing for development a natural fit. The expectation from Beijing, once it changed the principal contradiction facing Chinese society in 1978 away from class struggle and toward remedying the backwardness of productive forces, was that cadres at all levels would mobilize for this most fundamental, top-down mission.

The results of China’s campaign mobilization were mixed for the countryside in particular, where extensive appropriation from rural residents was common. As Looney notes: “China’s rural modernization is a story of huge successes and huge failures. During the 1980s, marketization, along with decentralization and decollectivization, resulted in unprecedented growth and poverty reduction…Over time, however, housing became the primary target of local efforts, and despite an initial emphasis on moderate change in this area, the policy evolved into a top-down campaign to demolish and reconstruct villages. Rural resource extraction continued in the form of land grabs, the rural-urban gap grew wider, and problems with the quality of goods and services surfaced. The Chinese case underscores how easily campaigns can spiral of control.” Looney, page 8.

The notion of regionally decentralized local governments and local officials competing within a context of developmental incentives is central to many analyses of what has distinguished China’s economic and political systems. See:

Chenggang Xu, “The fundamental institutions of China’s reforms and development”, Journal of Economic Literature, December 2011;

Pierre Landry, “Decentralized Authoritarianism in China,” Cambridge University Press, 2008.

For more on the mayor economy, or the constructive role of competitive local officials in economic development, see also Keyu Jin, “The New China Playbook”

China’s model operates via ‘good-enough institutions. See: Yuen Yuen Ang, “How China Escaped the Poverty Trap” and Yuen Yuen Ang, “Beyond Weber: Conceptualizing an alternative ideal type of bureaucracy in developing contexts,” Regulation & Governance, 2017.

Earlier analysis saw a federalist bent to China’s policies, though most are less sanguine this is the most useful frame for China’s uniaary system: Barry Weingast, Gabriella Montinola, and Yingyi Qian, “Federalism, Chinese Style: The Political Basis for Economic Success in China,” World Politics, 1995.

China’s model is perhaps sui generis. As Kellee Tsai writes: “Rather than promoting market-preserving federalism or a coherent developmental state, China’s fiscal reforms unleashed a remarkable diversity of informal adaptive practices and developmental strategies among local governments.” Kellee S. Tsai, “Off balance: The unintended consequences of fiscal federalism in China,” Journal of Chinese Political Science, 2004.

China’s Maoist-Leninist institutions touched on here were neo-traditional, in Ken Jowitt’s framing. These were harnessed or allowed to transmutate into a form of embedded and decentralized state capitalism, with neoliberal elements.”

For a deeper understanding of the institutional nature of China’s Leninist system, Ken Jowitt’s “Leninist Extinction” is a valuable resource.

For the argument applied to post-Mao China, see Jean C. Oi, “Rural China Takes Off: Institutional Foundations of Economic Reform,” May 1999.

Pierre Landry, “Decentralized Authoritarianism in China,” Cambridge University Press, 2008; Hongbin Li and Li-An Zhou, “Political turnover and economic performance: the incentive role of personnel control in China,” Journal of Public Economics, 2005.

Individual psychosocial benefits, e.g., status and distinction, and the ample potential personal gain also matter greatly.

Or, as the newly divined principal contradiction at the 1978 3rd Plenary of the 11th Centtral Committee put it, to remedy: backward productive forces” and return to taking economic development as the central task. Shi Dan (史丹), “Evolution of Principal Contradiction Facing Chinese Society and the CPC Leadership over Economic Work,” Institute of Industrial Economics (IIE), Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, May 2022, http://www.chinaeconomist.com/pdf/2022/2022-5/Shi%20Dan.pdf.

For a corrective against the excessive lionization of Deng’s role in bringing about this shift, also see: Julian Gewirtz, Never Turn Back, 2022.

The crazed race to lure production resulted in intensive expenditure. Keyu Jin states that between 1998-2007 foreign manufacturing companies were the most subsidized type of firm in China, on average getting multiples more than SOEs. See Keyu Jin, “The New China Playbook,” 2023, page 101.

On strategies used see:

The local role in economic development is both the curse and blessing of China’s development. For a time in the 90s and aughts, after the Party changed its principal contradiction to focus cadre competition on economic development, the decentralized authoritarian economic model conjoined the interests of the central government, localities, local officials, corporations, and most of the populous eager to benefit from rapid growth.

Whether local governments offered more of a helping hand or grabbing hand is still debated. But the results speak for themselves. Clearly an immense amount of development happened even in the presence of corruption and a certain amount of grabbing. Following the 1994 reforms, officials still had ample incentive to work with enterprises and, of course, to get involved themselves via LGFVs and other activities.

For a negative view of China’s fiscal centralization on switching local officials from helping to gabbing see: Chen, Kang & Hillman, Arye & gu, Qingyang, “From the Helping Hand to the Grabbing Hand: Fiscal Federalism and Corruption in China,” 2002, 10.1142/9789812778277_0008.

For a middle of the road assessment and the potential diversion of productive entrepreneurial and business activity to rent-seeking, see: Zhiqiang Dong, Xiahai Wei, Yongjing Zhang, “The allocation of entrepreneurial efforts in a rent-seeking society: Evidence from China,” Journal of Comparative Economics, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2015.02.004.

The other contender for most significant local government role is their aggressive courting of businesses to locate within their jurisdictions, particularly foreign firms that could contribute knowledge spillover and on-the-job training. Much more so than in other East Asian developmental states, courting FDI was a core contributor to China’s development, particularly the portion directed as export oriented manufacturing. Suffice to say that building infrastructure for companies to benefit from was often a core part of the enticements, meaning these roles—attracting business and building infrastructure— are not totally separable.

For more details on China Development Bank’s role in creating the Wuhu model LGFV, see the first chapter of Henry Sanderson and Michael Forsythe, “China's Superbank: Debt, Oil and Influence—How China Development Bank Is Rewriting the Rules of Finance,” Wiley, 2012.

And again, as noted in a previous footnote, some may argue Shanghai created the first LGFV in 1992.

“As Figure 1.1, taken directly from a CDB presentation, shows, land expropriation and the transfer of land rights are central to making the machine work, used for paying back the loan. “The city had land but no way to turn it into cash, so the government couldn’t get money,” researcher Yu says. “At that time, no one realized what Chen Yuan knew: that once the land price goes up, you have a second source of income.”” Henry Sanderson and Michael Forsythe, “China's Superbank: Debt, Oil and Influence—How China Development Bank Is Rewriting the Rules of Finance,” Wiley, 2012, page 8.

The role of Chen Yun, economic czar for decades, in creating the LGFV model is also noteworthy.

For good useful information the legal and institutional set up enabling local government’s to exploit the land, see: Chengri Ding, Yi Niu, Erik Lichtenberg, “Spending preferences of local officials with off-budget land revenues of Chinese cities,” China Economic Review, 2014, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1043951X1400131X

There were 41 instances of villagers self-immolating just between 2009 and 2012. NPR, “Desperate Chinese Villagers Turn to Self-Immolation,” October 2013. https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2013/10/23/239270737/desperate-chinese-villagers-turn-to-self-immolation.

My favorite encapsulation of the rise and fall of the peasant landholder can be found in Joe Studwell, How Asia Works ###

China today maintains four books as part of its budget: the general public budget, the government funds budget, the state capital operations budget, and the social security fund. Locally generated revenue is booked under the local portion of the general public budget. Central funds are also transferred via the general public budget. Land sales now show up in the government funds budget. For more see Tianlei Huang, “Lessons from China's fiscal policy during the COVID-19 pandemic,” PIIE Working Papers, March 2024.

For a discussion of local government’s in the negotiation process, see: Tsinghua’s ACCEPT,改革开放四十年经济学总结, 清华大学中国经济思想与实践研究院 Academic Center for Chinese Economic Practice and Thinking, ACCEPT, December 2018, page 49, http://www.accept.tsinghua.edu.cn/_upload/article/files/7a/3c/976c22ff48cfb1860f7288f6bd05/612c2ab9-2527-4237-b28e-7ce36ee2b379.pdf

For the seven connects and one leveling seeing: 七通一平 https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E4%B8%83%E9%80%9A%E4%B8%80%E5%B9%B3/801741

Tsinghua’s ACCEPT also wrote a rousing defense of the importance of the Party-state stepping in to help with land development: “land conversion is a crucial factor in the process of economic development that has been grossly under-emphasized in modern economics. Land is indispensable for the development of most economic activities, especially for developing countries that have not yet completed industrialization, and how quickly land can be converted from agricultural to non-agricultural land has an important impact on the process of industrialization and urbanization. Modern economics assumes that the process of land conversion is spontaneous through Coasean negotiations, but in reality, the transaction costs of Coasean negotiations are often high, so the process of land conversion, if spontaneous, will be expensive and slow.” See: 改革开放四十年经济学总结, 清华大学中国经济思想与实践研究院 Academic Center for Chinese Economic Practice and Thinking, ACCEPT, December 2018, page 35, http://www.accept.tsinghua.edu.cn/_upload/article/files/7a/3c/976c22ff48cfb1860f7288f6bd05/612c2ab9-2527-4237-b28e-7ce36ee2b379.pdf

Additional resources: Fulong Wu, Land financialisation and the financing of urban development in China, Land Use Policy, Volume 112, 2022 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837719306313)

Yi Feng, Fulong Wu, Fangzhu Zhang, The development of local government financial vehicles in China: A case study of Jiaxing Chengtou, Land Use Policy, Volume 112, 2022, 104793, ISSN 0264-8377, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104793 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837719313730)

Adam Y. Liu, Jean C. Oi, and Yi Zhang, “China’s Local Government Debt: The Grand Bargain,” The China Journal, 2022, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/717256; Adam Y. Liu, “Beijing’s Banking Balloon: China’s Core Economic Challenge in the New Era,” The Washington Quarterly, July 2023, 10.1080/0163660X.2023.2223838

See Adam Y. Liu, “Beijing’s Banking Balloon: China’s Core Economic Challenge in the New Era,” The Washington Quarterly, July 2023, 10.1080/0163660X.2023.2223838

Fuel was added to the banking system proliferation when the administrative structure of the big four/six bank branches was changed around the time of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998. Beijing apparently wanted to deny local governments the unfettered control over branches of the big four banks that they had been exploiting. Provincial branches of state banks were abolished, replaced with supra provincial entities, and most importantly: appointment authority of lower level bank officials was stripped from local Party cadres and given to the higher ups within the banking system itself.

This major change in bank personnel management represented a switch in what is called “vertical management” (part of ever shifting tiao/kuai governance). Local leaders could no longer strong arm same administrative level bank branches for loans at a whim. As tapping deposits at the big banks became more difficult, local officials found even more incentive to expedite development of local banks. The local government mouse skirted the Beijing cat.

See: Nicholas Lardy, State Strikes Back; and Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song, “The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion,” Becker Friedman Institute, November 2016, page 6.

See Adam Y. Liu, “Beijing’s Banking Balloon: China’s Core Economic Challenge in the New Era,” The Washington Quarterly, July 2023, 10.1080/0163660X.2023.2223838

Zhang Xiaojing (Institute of Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) Sun Tao (Financial Stability Bureau, People's Bank of China), “China's Real Estate Cycle and Financial Stability (Preliminary Draft),” Hong Kong Institute for Monetary Research 3rd Seminar on Mainland China Economy Real Estate and China's Macroeconomy, July 2005, page 12. 中国房地产周期与金融稳定 (初稿) 张晓晶 (中国社会科学院经济研究所) 孙 涛 (中国人民银行金融稳定局) 二 00 五年七月 https://www.aof.org.hk/uploads/conference_detail/767/con_paper_0_203_zhang-xiaojing-paper.pdf;

Henry Sanderson and Michael Forsythe, “China's Superbank: Debt, Oil and Influence—How China Development Bank Is Rewriting the Rules of Finance,” Wiley, 2012, page 13.

See some of the examples in the first chapter of Henry Sanderson and Michael Forsythe, “China's Superbank: Debt, Oil and Influence—How China Development Bank Is Rewriting the Rules of Finance,” Wiley, 2012.

Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song, “The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion,” Becker Friedman Institute, November 2016, page 15.

Indeed most LGFVs were likely already established prior to GFC era stimulus. In one study of county-level LGFVs, the authors note: “contrary to the common belief, most LGFVs did not emerge with the stimulus plan: 3,724 out of the 4,432 county-level LGFVs were founded before 2009.” Jianchao Fan, Jing Liu and Yinggang Zhou, “Investing like conglomerates: is diversification a blessing or curse for China’s local governments?” BIS Working Papers No 920, January 2021, page 15, https://www.bis.org/publ/work920.pdf.

Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song, “The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion,” Becker Friedman Institute, November 2016, page 2.

In 2009 PBOC Document No.92 explicitly calls on local governments to use LGFVs

See: Feng, Y., Wu, F., & Zhang, F, “The development of local government financial vehicles in China: A case study of Jiaxing Chengtou,” Land Use Policy, 2020, page 4.

Meanwhile, here’s what CBRC said in 2009, “Encourage local governments to attract and to incentivize banking and financial institutions to increase their lending to the investment projects set up by the central government. This can be done by a variety of ways including increasing local fiscal subsidy to interest payment, improving rewarding mechanism for loans and establishing government investment and financing platforms compliant with regulations.” Document No. 92, CBRC, March 18, 2009.

“Allowing local government to finance the investment projects by essentially all sources of funds, including budgetary revenue, land revenue and fund borrowed by local financing vehicles.” Document 631, Department of Construction, Ministry of Finance, October 12, 2009.

For the regulations and quotes see Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song, “The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion,” Becker Friedman Institute, November 2016, page 10.

Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song, “The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion,” Becker Friedman Institute, November 2016, page 15.

Chong-En Bai, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Michael Song, “The Long Shadow of a Fiscal Expansion,” Becker Friedman Institute, November 2016, page 15.

On the credit estimates see: Andrew Collier, “The Rise of the LGFV” in Shadow Banking in China, page 55; see for related discussion: Henry Sanderson and Michael Forsythe, “China's Superbank: Debt, Oil and Influence—How China Development Bank Is Rewriting the Rules of Finance,” Wiley, 2012, page 14.

Full catalogues were only released in 2006 and 2018. There was a net increase of 330 national-level development zones and a net increase of 850 provincial-level development zones, the only two levels included in the list. In 2018, tthere were 552 national-level development zones, 1991 at the provincial level, and countless more at the city and county level. See the NDRC’s catalogue of such parks and zones published in 2018: 中国开发区审核公告目录(2018年版)https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fggz/lywzjw/zcfg/201803/t20180302_1047056.html; see the NDRC’s 2006 catalogue: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/gg/200704/W020190905487497735524.pdf.