Sergey Radchenko’s book, To Run the World: The Kremlin’s Bid for Global Power, is a masterwork! In my mind, it’s in pole position for best book of 2025. Sergey takes you into the mind of Soviet and Chinese leaders as they wrestle for global power and recognition, leaving you amused, inspired, and horrified by the small-mindedness of the people who had the power to start World War III.

We get amazing vignettes like Liu Shaoqi making fun of the Americans for eating ice cream in trenches, Khrushchev pinning red stars on Eisenhower’s grandkids, and Brezhnev and Andropov offering to dig up dirt on senators to help save Nixon from Watergate.

Sergey earns your trust in this book, acknowledging what we can and can’t know. He leaves you with a new lens to understand the Cold War and the new US-China rivalry — namely, the overwhelming preoccupation with global prestige by Cold War leaders.

In this interview, we discuss…

Why legitimacy matters in international politics,

Stalin’s colonial ambitions and Truman’s strategy of containment,

Sino-Soviet relations during the Stalin era and beyond,

The history of nuclear blackmail, starting with the 1956 Suez crisis,

Why Khrushchev’s vision of abundance couldn’t save the Soviet economy.

Co-hosting today is Jon Sine of the Cogitations substack.

Listen now on iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast app.

Why Authoritarians Need Legitimacy

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start with prestige. How do you define it, and is it anything bigger than just schoolyard dynamics?

Sergey Radchenko: That’s a deep question, and that’s where the Soviet experience is not actually unique. If you think about the Soviets pursuing prestige, what’s so unique about that? Everybody does that. People strive for status, people strive for recognition, and states do the same thing.

That is why in the introduction to my book I try to zoom out a little bit — I’m trying to say is that the striving for recognition is not something unique to Soviet leaders. In fact, I show that even during the Cold War, the Soviets were not unique. The Chinese also had similar motivations and sometimes also the Americans.

We’re starting to throw around difficult terminology — recognition, prestige — what do those things mean? To add to the complexity, what the Soviets really wanted was legitimacy. Everyone wants legitimacy, but the Soviets had a particular need for legitimacy perhaps because of their lack of internal legitimacy. They had a project on their hands. They wanted to pursue a communist revolution. They were trying to sell it to the Soviet people saying, “Look, soon we will be living under communism. Everything will be so fine. We’ll all be so wealthy.” The abundance, material abundance was supposed to come soon — and it didn’t.

It didn’t arrive because the Soviet project had already started losing steam by the late 1950s. It became increasingly clear that this was happening, creating a deficit of internal legitimacy. Because of that, they wanted external legitimation. They wanted others to say, “You’re great, you’re wonderful, you’re a superpower,” because then they could turn to their own people and say, “Look, we are so strong, we’re a superpower, we’re great because they say so.“

Who are they? Of course, the ones in a position to recognize — the Americans. Others mattered too. If Mongolia or Papua New Guinea said, “This is the great Soviet Union,” that was important. But if the Americans said that, it was all the more important because they were themselves a superpower, so their recognition was absolutely crucial for the Soviets’ sense of greatness. That is where those things connect — prestige, recognition, external recognition, and legitimacy.

Jon Sine: I’m trying to understand what legitimacy from an international perspective gets you. I’m reminded of the phrase, “Foreign policy is domestic policy by other means.” How is a foreign policy of recognition — this external validation — important from a domestic standpoint? Is this what is driving it, or is there some other source driving this need for recognition and legitimacy?

Sergey Radchenko: There may be an acceptable definition — legitimacy is legality and justice put together somehow. It’s a term that reflects legality — a legal position — and justice, meaning you deserve that position.

The Soviets really wanted to be seen to occupy a place they deserved. They tried to sell this to their own people, saying, “Look, we are in this position, we’re great, we deserve to be great, they recognize us as great, we are legitimately great.” This is to be distinguished from raw power.

I show in the beginning of the book how Stalin sometimes actually wanted legitimacy instead of raw power. In some cases where he controlled certain territories, he would back off because he wanted legitimation of his control — legitimate control, not just absolute control by sheer power.

I can give you a couple of examples. One example would be the separatist rebellion in Xinjiang. Stalin supported the rebellion in Xinjiang but then backed out. He basically sold the rebels down the river and engaged in a relationship with the central government in China. Although that meant he lost immediate control of Xinjiang, he acquired a certain sense of legitimacy for his other claims in China.

That is where power and legitimacy were in a state of interplay, and sometimes — not always — but sometimes Stalin would prioritize legitimacy over power. That’s not to say he would always do that. There was a certain bottom line where he would say, “No, I refuse to give up that particular thing because it’s absolutely essential for my security or what I feel is necessary for the USSR.” But sometimes he would say, “I will give this up if you recognize that whatever else I hold here is legitimate,” and that is the essence of the Yalta framework that was constructed in 1945, which Stalin was very fond of and wanted to preserve.

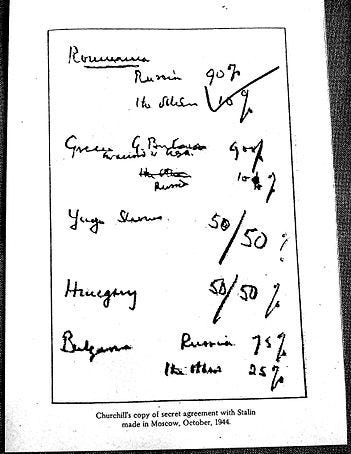

Jon Sine: Staying on the Yalta agreement, one of the things that quite surprised me in the book is how interested Stalin was in a concert of powers and having his view of the USSR’s proper sphere legitimated. Could introduce the percentages agreement?

Sergey Radchenko: The percentages agreement is a well-known episode in the early history of the Cold War. Churchill went to Moscow and met with Stalin in October 1944. Churchill in his memoirs recounts it by saying basically, “I wrote down percentages of influence that the Soviet Union and Great Britain would have in southeastern Europe, and then I gave the paper over to Stalin. Stalin made a tick on it, handed it back to me, and I told Stalin, ‘Maybe we should destroy this piece of paper, because isn’t that very cynical that we basically decided the fate of millions of people in this way?’ And Stalin said, ‘No, you keep it.’”

What’s interesting — this story, of course, is decades old. We’ve all known about it from Churchill’s memoirs. But this is where writing international history becomes really interesting — now we have the British version of the record of conversation, we also have the Russian version of the record of conversation. We have the actual piece of paper in the Churchill archives, the percentages agreement, and crucially, something that has not really been considered before: we have extensive discussions that followed that agreement between the Soviets and the British about specific percentages.

When I was reading those discussions, I thought, “This is so strange, the Soviets really took this stuff seriously.” They argued about an extra 5% in Hungary, this kind of stuff. You think, “Really? What does it even mean?” It sounds bizarre, it sounds absurd, but that shows that Stalin really took that seriously. He felt that he had a legitimate sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. He was very cynical about it, but he basically expected the British and the Americans to defer to his desires in Eastern Europe, and in turn, he would accept the British and American sphere somewhere out there.

He wanted his sphere recognized externally. The problem was that what Stalin considered a legitimate sphere of interests or sphere of influence was not seen as legitimate by the Americans, in particular. That explains a lot about the way the Cold War unfolded.

Jon Sine: Throughout the rest of the book, it’s not clear if any of this is really worth it. But in this particular instance, when you talk about America pushing back on Stalin, you do seem to think that it was very necessary for America to have done that. Basically the Cold War, in a sense, was not inevitable from an ideological perspective, but rather happened because Stalin was going to push until he found resistance. Could you elaborate on your views on that?

Sergey Radchenko: It’s a difficult question. Historians have looked at the early Cold War and have tried to understand whether Stalin was perhaps open to compromise. Some have said that he was looking for great power compromise, and I’m also inclined towards this view. Others would say, “No, we had to stop Stalin’s expansionism, and Stalin could never be trusted,” and so on.

The problem from the US perspective is we’re all wise in retrospect — we can look at the Soviet archives and hopefully understand what Stalin actually was thinking. But the problem at the time is you are facing this difficult person called Joseph Stalin. Nobody knows what he’s thinking. Nobody knows what his ambitions are. Does he want to take over the world or not? Does he want to take over Europe? I show in the book that Soviet post-war planning entailed Soviet control over much of continental Europe, as far as Sweden. They had great appetite.

There’s great uncertainty. You’re in the present moment, trying to deal with the situation, you don’t know what the other guy thinks, so what is the safe policy to pursue? I cannot imagine a safer policy than that which was actually pursued in terms of what George Kennan formulated in The Long Telegram, the policy of containment, the policy of pushing back.

Did that help bring about the growing distrust with the USSR and in some ways precipitate the Cold War? Maybe. Of course, if you’re pushing back on a guy, he’ll think, “Look, they’re aggressive, they’re pushing back on us.” But if you don’t push back on the guy and it turns out he’s actually determined to take over the world, you’ve got a problem.

In the end, what happened — containment — is, I guess, the best worst solution in the situation that we had in the early Cold War. It’s a tragic situation. It’s a situation that results from the lack of trust and from inability to understand or know in real time what the other side is thinking. We can project this onto our own days and ask similar questions, but maybe we can do it later.

Jordan Schneider: It’s fascinating how you see these leaders ending up resorting to the lowest common denominator of understanding the other side. Stalin basically says, “The West only understands force. When you have an army, they talk to you differently. They will recognize and learn to love you because everybody loves force.” Truman basically did the same thing. He was like, “I got a bomb, they gotta listen to me. I can bully him however I want.“

There are moments over the course of the Cold War where leaders start to feel their way to slightly different dynamics, where it’s not just this whole idea of prestige and national power as this gas that inevitably expands until you hit another great power that’s going to push back on you. Perhaps there are different ways in which you can look at those points of contention and try to devise different operating systems.

It’s remarkable and almost speaks to the argument of prestige being this gaseous force that these two countries who had just fought a world war together were not able to figure out how to get their interests to align in a way that wouldn’t lead them down to what the world ended up having to live with for the next 50 years.

Sergey Radchenko: It’s partly that, Jordan, and partly just a different conception of the world. We can get attached to the person of Stalin and say that he was paranoid and crazy, but if you look at Soviet post-war planning, it was based on a kind of 19th century imperial model. The Soviets get to control a lot of territory like the Russians when the Russian empire was expanding. Stalin was thinking in 19th century terms, very unremarkable given that particular historical period.

Churchill was like that, by the way. The Americans were not thinking in those terms. They were coming from a different perspective, and they did not want to allow the Soviets to basically put Eastern Europe into their pocket and walk away. From that, you already see a clash of visions for the post-war order, multiplied by the lack of trust, multiplied by security concerns. You can see how you would have the slide towards confrontation

There were also other factors. One point I raise in my book is that early on — 1945, 1946 in the early post-war world — Stalin was hopeful that the communists would come to power in many places unaided. People would just vote for them because they were so popular and wonderful. Then it turned out that in Eastern Europe nobody thought that, so he had to falsify elections in Eastern Europe. This raises a question. It becomes much more difficult to pretend you can have some kind of cooperation or a coalition of governments.

The same thing happens in Western Europe where the Italian Communist Party and the French Communist Party were initially very popular but then ultimately had to effectively leave the government. Stalin realizes that he will not be able to obtain more pro-Soviet governments or Soviet leaning governments through coalition partnerships and resorts to brute force. That’s another factor I wanted to highlight.

Jordan Schneider: If Stalin is expecting 70% of Europe and the West is expecting 70% of Europe, then was there ever really a way to find some happy medium if their desires of what they wanted the world to look like after 1945 were fundamentally incompatible?

You zoom in very directly to 1947, where Stalin wakes up to the fact that unless he starts playing hardball, he might be losing on a lot more fronts than he was hoping to. But in the hypothetical where communism happens to be more popular and win elections, is this something the CIA even stands for in the first place? It’s hard to imagine, if that is Stalin’s base case, that you really could have ended up anywhere else.

Sergey Radchenko: Exactly. That’s why I’m so cautious. I’m not a revisionist historian saying, “If only the Americans behaved themselves better and understood Stalin or accepted Stalin’s sphere of influence, then it would all have turned out fine.” Maybe it would have, but another thing we need to keep in mind is that Stalin measured his appetites in part as a result from the policy of containment.

If the Americans were not pushing back, who knows whether his appetites would have stayed where they are or would have extended even further. That is why I’m saying we don’t know, and he himself may not have known at that time. That’s why containment was the safe policy.

It is a tragic outcome. Yes, it does contribute to the Cold War, but who could come up with a better policy than containment when you don’t know who you’re dealing with on the other side? Frankly, looking at Stalin’s paranoia and his dark view of the world and his obsession with conflict, it would have been a very unwise policy to try to indulge Stalin too much. I’m saying that as somebody who’s read a lot of Stalin. I think containment was a wise strategy.

Jordan Schneider: I love this little riff you go on in your book, which is a historical wrinkle I wasn’t aware of, where Stalin was like, “Let’s see if we can get some colonies in Libya.” Can you explain that?

Sergey Radchenko: It’s remarkable, isn’t it? Absolutely remarkable. Here again, 19th century European imperialism and colonialism — that’s how Stalin was thinking. “Oh, Africa? Of course. Those other guys have colonies in Africa. Why shouldn’t we have a colony in Africa? We can try our hand.” I think Molotov said something along the lines of, “We can try our hand at colonial administration.”

They, by the way, early on felt that the Americans had promised them something along those lines. Then when James Byrnes became Secretary of State, it turned out that he didn’t want to go in that direction, and Stalin felt his expectations were betrayed.

Why did he want this colony in Africa? Strategic reasons maybe. More important are the issues of prestige that we talked about, because if you’re a great power, of course you want to be in Africa. That’s where all the great powers made their imprint. That’s why he wanted to go there.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s turn to Asia. What happened with Hokkaido?

Sergey Radchenko: The Hokkaido story is fascinating. Basically, Stalin got this idea that the Soviets should help in the liberation of Japan and proposed effectively landing on the island of Hokkaido.

Remember, in 1945, the Japanese controlled not just Hokkaido, but also what they called Karafuto, or southern Sakhalin Island — that’s the place where I grew up — and the Kuril Islands as well. The Soviets liberated those islands as part of the Yalta agreement, which was stipulated in the agreement.

Stalin then said, “We can also land on Hokkaido. There’s a wonderful island off Hokkaido. Let’s liberate Hokkaido as well.” He proposed that and sent a telegram to Truman. Truman basically said, “There’s no way this is going to happen,” and remarkably, Stalin backed off.

You have to ask the question, why did he back off? The obvious answer — we’re talking about mid-August 1945 — would be that he was afraid of the atomic bomb. That’s one possible answer. Is it credible? There’s something to it.

Another possible answer is that he was interested in preserving some sort of cooperative relationship with the United States. The Yalta agreement was in place, the Americans respected it, and he wanted that recognition and that legitimacy offered by Yalta.

In fact, he continued for some years, until 1949, almost 1950, to abide by the principles of Yalta because he wanted American recognition of the legitimacy of his gains. When Truman said, “No, sorry, you cannot. That’s just too far. You were never there, do not even come close,” Stalin backed off.

It’s interesting — it wasn’t just fear of the nuclear bomb, it was also concern about maintaining a cooperative relationship with the United States. It could be both. History is multi-causal.

Socialist International Relations(唇亡齿寒?)

Jordan Schneider: Another example of Stalin not going all in right after 1945 was the way he handled Mao and the nationalists. Can you talk about how Stalin handled China throughout the civil war?

Sergey Radchenko: That is a very interesting aspect of Soviet foreign policy which I think is understudied. If you look at histories of the Cold War, they all focus on Europe, on the German question more or less, and few people actually examine China.

What you see in China’s case is something quite remarkable. Soviet involvement with China predates the Second World War and goes back to the 1920s. The Soviets were helping both the Kuomintang and at one point were crucial to the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party. Then you have this period of prolonged confrontation between the Kuomintang and the Chinese communists.

The Chinese communists, following the Long March, retreated towards Northwestern China and were headquartered in a place called Yan’an. That is where the end of the Second World War finds Mao. He receives a telegram from Stalin in August 1945 saying, “Go negotiate, go to Chongqing,” which is the military capital of China, “Negotiate with Chiang Kai-shek for a coalition government.“

You can imagine how Mao would react to this. “What? Hang on just a second. We are not friends. We have had a very difficult relationship.” Yes, there was a period of united front and during the war against the Japanese they even cooperated in some ways, but Mao was not keen to have this sort of relationship with Chiang Kai-shek or to enter into a conversation with him.

Mao was basically forced by Stalin to do that because Stalin had concluded the Treaty of Alliance with Chiang Kai-shek. That was a result of very painful negotiations in Moscow. Chiang Kai-shek sent T. V. Soong, who was the head of the Executive Yuan, to Moscow for those negotiations.

What Stalin was able to wrestle from Chiang Kai-shek was not only concessions in China — there’s a discussion of the railroad that the Soviets sold to Manchukuo but now wanted back — but also, crucially, he got Mongolia. The Soviets had been controlling Mongolia for a long time, but de jure it remained a part of China. Stalin wanted Chiang Kai-shek’s government to say, “Okay, we give up on Mongolia.” That was arranged in Moscow in 1945. These were massive concessions.

What did Chiang Kai-shek want in return? I mentioned one of those demands: the end of Soviet support for Xinjiang separatists, and Stalin agreed. Stalin claimed, “We don’t know what’s happening in Xinjiang. This is not us.” Although the whole war was being fought with Soviet weapons and instructors. He said, “No, no, no, that’s not us.” Basically, he gave up and betrayed those separatists in Xinjiang, saying, “Okay, we’re done with you.“

Then the question of Mao Zedong came up, and Chiang Kai-shek said, “Look, you’re supporting Chinese communists.” Stalin replied, “Well, Mao is not really a communist, he’s just a nice guy but he’s not a communist.” As a result, Stalin got his gains in China, he got Mongolia, and he basically told Mao to go negotiate with Chiang Kai-shek.

Stalin had to understand what this meant. If Mao Zedong negotiated with Chiang Kai-shek for a coalition government — we’ve been there, we’ve done that already before. Mao did not have a superior force, and Stalin understood this. Stalin thought that the Kuomintang was a much stronger force in China in 1945. This basically meant surrendering to the Kuomintang. I think Mao also understood that.

There’s this very interesting period from 1945 until the Chinese Civil War broke out again where Stalin was uncertain who he would support or what his position in China should be. He was interested in a solid relationship with the Kuomintang because they had guaranteed his control of Mongolia and those parts of his imperial interests, ratified by the Yalta agreement. That was much more important to him than Mao’s cause and communism.

Later he changed his mind, but that was because the Cold War started to unfold in Europe and he thought that maybe he should have stuck with Mao Zedong after all. But that took place over a period of time, which is why Mao later said on numerous occasions, “Stalin blocked our revolution and regarded me as a half-hearted Tito.” Mao had every right to say that, because Stalin did not believe in the victory of the communist revolution. When it happened, it was a great surprise for him.

Jon Sine: America also sent George Marshall (there’s a great book on this called Marshall’s Mission to China) to try to ensure this compromise between the communists and the nationalists. You’re telling us we have Stalin pushing on the communists to make this work. So what goes wrong?

Sergey Radchenko: What doesn’t work is that Mao does not want to have anything like that in place. Stalin has limited leverage over him — he cannot force him to agree to a coalition government. He can only advise him to have a coalition government.

They have long discussions in the fall of 1945 when they meet in Chongqing. There’s extensive discussion there about what future China might look like. The Chinese communists actually propose effectively dividing China along a north south scenario where the north is controlled by the communists and the south is controlled by the Kuomintang.

Chiang Kai-shek cannot accept this because he is a nationalist, a patriot. He does not want a division of China like that, so he turns this down. They never could agree, and then ultimately you’ve got George Marshall’s intervention in the period of quiet.

Later, Chiang Kai-shek blamed George Marshall for interfering too much, claiming that if his hands weren’t tied, he would have been able to wage war much more effectively against Mao Zedong and would have defeated him.

That’s a whole different story as to why nothing works out and why the civil war is won by the communists. Many historians have written about this — it’s not part of my book — but there were serious problems with the Kuomintang government and the state of the Kuomintang army. That’s the bottom line.

Jon Sine: Let’s fast-forward to the late ‘40s, at which point the communists are moving into Manchuria. You have this piece of evidence — I think it’s Stalin writing to a general operating in Manchuria on behalf of the Soviets — and he says something to the effect of, “If Mao and the communists move in and try to take any of the material, open fire or use force to prevent this.” This really speaks to your narrative. Could you explain what that source is and what Stalin was doing there?

Sergey Radchenko: That comes from one of Stalin’s telegrams. I think it was to Rodion Malinovsky, who later became the Soviet Minister of Defense if I recall correctly.

The situation was that Chinese communists were trying to get into Manchuria because that’s a very important base to have, and they’re trying to occupy Manchurian cities. The Kuomintang government was obviously determined to prevent them from doing that.

The Soviets were actually in control at that time in Manchuria before they ultimately withdrew. Stalin instructed his forces on the ground to deny Chinese communists the ability to enter the cities. This is remarkable if you think about it because, aren’t they supposed to help Chinese communists? They’re the Soviet Union, a communist country — aren’t they supposed to help communists?

The communists say, “We want to get into the cities, we want to control Manchuria,” but Stalin sends a telegram saying, “Keep them out. Open fire if they try to do that.” I can’t remember the exact term that Stalin used — it’s like “these people” or something like that. It’s as if he’s saying, “I don’t trust these guys.” He says, “They are trying to get us into conflict with the United States.“

Is he right? Of course he’s right. The Chinese communists would have been very happy at this point if the Soviets and the Americans came to blows. But that’s still too soon right after the end of the Second World War, and Stalin is of the mind that he should: A) avoid a conflict with the United States, especially over China, and B) work with the Kuomintang government.

He is pursuing a policy of great duplicity. He is tolerating the Chinese communists in the countryside, but he’s keeping them out of the cities. The Soviets were helping communists by providing them supplies over the border. I don’t want to say that he completely rejected the Chinese communists — he was basically playing both sides.

It’s very clear that he was in fact trying to keep communists from taking over cities in Manchuria, and I think that is really a new piece of evidence that contributes to our understanding of what his China policy was from 1945 until 1946

Jon Sine: Let’s zoom out and talk about Stalin’s China policy from a macro perspective. I was reading Stephen Kotkin’s book, the first volume of his Stalin biography, and he basically pillories Stalin’s China policy. He looks into what the Soviets were themselves talking about back in the ’20s when Stalin was suggesting that the communists should ally with the nationalists, which ended in an absolute massacre of the communists by the nationalists.

Kotkin’s view is that Stalin’s China policy has been a string of really atrocious decisions about how to operate there. How does this ultimately reverberate with Mao, thinking about his position vis-a-vis Stalin, someone who has really screwed him in a number of ways, and who then has to deal with Mao coming into power in ‘49? Mao has to maintain a sort of subservient position to Stalin as the long-term leader of the communist camp. How does that all play into this?

Sergey Radchenko: Clearly Stalin and Mao did not really like each other, and Mao had very few good things to say about Stalin. However, he understood that Soviet support was really important for the long-term survival of the communist regime in China and for recognition of the communist regime. Here I mean literal recognition because once the Chinese take over, they need recognition from the Soviets.

The Soviets were very keen to offer that right away, although not without some side stories. For example, when the Chinese communists take over Nanjing, the Soviets follow with the retreating Kuomintang to Guangzhou. The Chinese communists are asking, “What are you doing? Even the Americans are staying in Nanjing!” The Soviets respond, “You don’t understand strategy.”

For Mao, it was essential to get Stalin’s support, Stalin’s diplomatic recognition of the Chinese communists as a legitimate regime, but also aid — Mao counted on Stalin’s aid in the reconstruction of China and on Soviet protection.

There are all kinds of good reasons why, despite his not particularly good feelings towards “Comrade Main Master,” as Mao called Stalin, he still went along and respected Stalin. I think I say in the book that it’s almost in the way that, in a large family, perhaps a son would respect his father in a Confucian way, although Mao always liked to emphasize that he was not a Confucian. It’s almost like he’s paying respect without really liking Stalin very much at all.

I don’t know if you saw that in the book, but I dug out this absolutely hilarious document which I quoted from. Mao sent his wife, Jiang Qing, to Moscow, and she was there in 1949 undergoing medical treatment. She wrote letters to her “beloved chairman” and these letters are in the Stalin archive in Moscow, which obviously shows that they were being read and delivered to Stalin.

The funniest thing is, Jiang Qing surely knew that they were being read, so she would start the letter with, “Oh, my dear beloved chairman, I miss you so much, loves and kisses.” And then she would say, “Oh, we have to be very clear in our condemnation of Tito’s revisionist clique” or something like that.

Sergey Radchenko: It was very important for Mao to actually prove to Stalin that he was a loyal supporter, that he was not a Tito who could betray him. That’s what he tried to do. Very pragmatic on his part.

Mao did declare in 1949 that he would “lean to one side,” the Soviet side, which led later to historians debating this moment, asking, “Was there a lost chance? Was there an opportunity for the Americans to stay in China and avoid 20 years of disengagement?“

Back in the ‘90s when these debates were being held, the conclusion by most historians — people like Odd Arne Westad and Chen Jian and others — was that no, there was no lost chance because Mao was so ideologically connected to Stalin. Also, he had in mind this project of Chinese communist revolution that was so important to him. He had to “clean the house before inviting guests,” i.e., kick out the Americans and then carry out these revolutionary transformations.

I am not 100% sure about this because I don’t think anything is definite until it actually happens. My own view is that perhaps if the Americans had a different approach to Communist China at that time, there would’ve been an opportunity to establish relations.

Stalin and Mao coordinated their policy on this question. The expectation on the part of the Chinese communists would be that the Americans would derecognize Taiwan effectively, or derecognize the Kuomintang government and extend recognition to the communist government. That was the key issue for them. Beyond that, it’s not like they were absolutely determined to break diplomatic relations with the United States.

Jordan Schneider: This older brother, younger brother, father-son dynamic between Stalin and Mao plays out wonderfully the way you talk about the face-to-face meetings they have. Mao gets really disrespected the first time he goes to Moscow. Stalin makes him wait for a while and basically says no to everything he asks. Slowly but surely over the course of Stalin and even more dramatically with Khrushchev, the national power balance as well as the revolutionary legitimacy (i.e. who is leader of the communists) shifts over time.

Let’s maybe use that as a way to start talking about the Korean War. How did their relationship and this Chinese-Soviet dynamic play out in 1950, which brought about that horrific conflict?

Sergey Radchenko: The Korean War has been studied by so many people. We have had a lot of documents that have been studied closely by historians since the 1990s on the Chinese side, the Russian side, and even on the North Korean side. This is really a well-studied conflict.

I wondered if I’d have anything new to say about this. In a massive book like this, I had to say something about the Korean War. I was actually quite lucky in the sense that I did find some new evidence. It wasn’t a smoking gun type evidence, but it came close. I’ll explain the nature of the evidence.

Basically, the story goes like this. Kim Il-sung in North Korea wanted to reunify the country and kept asking Stalin for permission, saying, “Comrade Stalin, the moment we cross over the 38th parallel, there will be revolution in South Korea. Everything will turn out just fine. It’ll be very quick.” Stalin would refuse him permission to do that time and again. The reason for that is pretty obvious — Stalin was worried about American intervention. He was a very cautious individual in this particular instance.

Then he changed his mind. It’s not exactly clear when he changed his mind, but we know that in late January 1950, Kim Il-sung was at a reception. Kim was a little bit drunk, went up to Shtykov, who was the Soviet representative in Pyongyang, and said, “We want to reunify South Korea.” Shtykov reported that to Stalin. Stalin sent a cable back to Shtykov for informing Kim Il-sung that “this matter requires preparation.” That is already a yellow light, not a red light.

Later, Kim Il-sung went to Moscow, and they effectively agreed that the invasion would start. He changes his mind around late January 1950, or at least he tells Kim Il-sung around that time.

Various theories have been advanced. The most obvious is that at that point, there’s already going to be an alliance with China, so as a worst-case scenario, the Chinese could fight this war if Kim makes a mistake, or if the Americans intervene. But I think if Stalin thought that the Americans would intervene, he would never have authorized Kim Il-sung to do that.

The question is, why does Stalin change his mind from thinking that the Americans might intervene to thinking that they will not intervene? That is where it becomes complicated.

First of all, we have Dean Acheson’s remarks in the press conference, which are straightforward, where he says, “America has a defensive perimeter, which does not include Korea.” That is probably the most misguided statement ever made by an American foreign policymaker. That, in retrospect, was a very bad idea.

Beyond that, there’s been speculation by historians that Stalin had spies who had access to debates at the center of American power in Washington. The problem with that is, of course, we didn’t have any evidence. We can just say, “Stalin has spies everywhere. That’s how he knew about certain things like NSC-48, for example.“

What I found was very interesting. I was reading a discussion between Mao Zedong and Anastas Mikoyan in 1956 during the 8th Party Congress in Beijing. Mikoyan comes to Beijing in September 1956. They’re having discussions. Stalin is dead for more than three years, right? Suddenly the discussion turns to North Korea, and Mao says, “Why did you agree to let Kim Il-sung cross over and start the war?“

When I saw this, I thought, “That’s a moment right there. That’s very interesting.” Even Mao himself did not know what was going on. Stalin did not inform him.

Then I see Anastas Mikoyan’s response, which is, “Our intelligence intercepted cables by the Americans that said that they would not intervene in the conflict.” That is super interesting because you get that one little piece, one acknowledgement, one little piece of information that you can weave into the narrative and say, “The role of intelligence was very, very important.” This is basically from the horse’s mouth.

Mikoyan says that three years after Stalin died, “Actually, the reason we did this was because we misinterpreted the intelligence that we intercepted.” That is where it all goes wrong.

The nature of the intercept, I couldn’t find that in the archives. By the way, this document of Mao Zedong’s conversation with Mikoyan is actually from the Chinese archives, not the Russian archives. When I went back to the Russian archives, I couldn’t really find anything about that. It’s probably still somewhere locked away in the KGB vaults.

Jon Sine: My thinking is this is one of the places where there might be a lesson for today that screams at you most clearly. Do you think Joe Biden was playing 4D chess, learning from Dean Acheson, when he kept making these mistaken statements about Taiwan that his staff would later clarify by saying, “That’s not really what he’s saying,” while he maintained, “We’re going to protect Taiwan”?

Sergey Radchenko: That’s a whole different conversation regarding strategic ambiguity versus strategic certainty and which approach is better. The discussion has typically gone like this — If Biden remains unclear or maintains ambiguity about what the United States would do, that might potentially trigger Chinese intervention because they would underestimate American resolve to defend Taiwan. If, on the other hand, he stated very straightforwardly, “We will actually defend Taiwan,” then this would tempt the Chinese to test American resolve by invading Taiwan.

You can twist this argument in many ways. The bottom line is that you have internal debates and external communication between leaders. You have statements that can be misinterpreted and often are. This is how we slide into conflicts and wars — sometimes by misinterpreting what the other side wants us to do, or will do, or will not do, by underestimating the other side’s resolve.

The best example from our present situation is that Putin underestimated the resolve of Western powers, particularly the United States and Europeans, to help Ukraine. He underestimated the extent of their commitment, although that commitment has now started to fade away in some instances. Certainly in February 2022, he did not anticipate that level of commitment. Why? Because Crimea was a different story and nothing meaningful happened after Crimea, so he learned from that experience. It turns out the response this time was very different.

This parallels the early Cold War. There would be one type of strategy, and then the Soviets would do something completely reckless, like initiating the Korean War, which would reinforce the thinking in the United States that the Soviets must be confronted and pushed back against, even in a place like Korea. From Korea not mattering to anyone and nobody being able to find it on any map, suddenly it becomes the center of American attention, with people going there to die on behalf of the free world. Who would have thought? That’s a change of attitude, and it happens over weeks and months.

Jordan Schneider: This is one of the big lessons I took away from your book — the leaders are playing this weird game. Dean Acheson said it and probably believed it. Then when it happened, the politics changed, and everyone decided that it’s one thing to project it out, but when you’re faced with the reality, the news, the headlines, and the threat to prestige that all these people weigh so heavily, then perspectives change.

It’s also remarkable how you illustrate, by delving deeply into these leaders and their profiles, that they often don’t even know what the plan is. You see them winging it frequently. So even the idea that you can try to guess what your adversary is doing and play 3D chess when they themselves or even their lieutenant is thinking, “I don’t know what we’ll do next” — it’s wild to internalize that there are so many unknowns where one path could lead to the end of humanity.

Sergey Radchenko: Exactly. That’s the weird thing about Cold War history. Things could have taken terrible turns. They could have also turned out better than they ultimately did. We did have terrible crises during the Cold War, and at those particular moments, we should be grateful that leaders, despite all of their confusion and inability to understand what the other side was thinking — or maybe because of it — decided to de-escalate and pull themselves away from the brink. That is something that should be acknowledged.

Jon Sine: One of my lessons, and this might be the bridge from Stalin to Khrushchev, is how much these prestige battles mattered. It makes me think much of the Cold War was really just a sad, pointless endeavor of people jockeying over imaginary status points and where they sit in various social groupings. They’re getting pulled into games by third-party players while imagining it’s part of a broader struggle they have defined for themselves among their own group.

The Korean War is an interesting point because this is where America comes to push back, and what ends up happening is we now have a divided Korea. Fast-forward to today, and it seems like one of the most worthwhile interventions from the Cold War. But then you look to other cases, Vietnam being an example of an atrocious intervention. I’m wondering how you think about that — when America decides to intervene and when it becomes a really costly and pointlessly costly endeavor versus something that was worthwhile?

Sergey Radchenko: That’s a difficult question. It entails a moral judgment, and it’s difficult to make because, for example, the Korean War could have ended up as a nuclear war. Didn’t Douglas MacArthur want to use nuclear weapons, or at least threaten to do so? It could have happened but didn’t, and so if it did and we ended up having a nuclear catastrophe in Northeast Asia, would we be better off “dead rather than red“? It’s difficult to say.

In the end, it kind of worked out despite millions of casualties. It was a terrible, destructive war with so many deaths, but we can say in retrospect, “Look, the Americans stood up to defend freedom” — not quite democracy, frankly, because Syngman Rhee’s regime was not exactly democratic, but years and decades later it all worked out. Was it worth it? Probably.

By the same token, you might even say the same thing about Vietnam. One of the things I discovered while looking at Soviet documents — and the Soviets had remarkable access to the Vietnamese Politburo. Somehow they had spies there because in the Soviet archives you have speeches of Vietnamese Politburo members. So internal documents and all sorts of things from Vietnam that you wouldn’t expect. The Soviets clearly knew a lot more about what was going on.

You read these Vietnamese documents and recognize that actually Eisenhower’s domino theory was not wrong in the sense that that’s exactly what the Vietnamese wanted to do. They wanted to reunify their country and then promote revolutions. They obviously wanted to control revolutionary movements in Laos and Cambodia, but in the late 1960s they were discussing starting a communist revolution in Thailand, and I don’t know why that particular project didn’t work out for them.

When you read something like this, you think, “Wait a second, this is the domino theory. That’s what they’re talking about.” The Americans got involved and that was very tragic. You can turn to almost any historian of the Vietnam War and they’ll tell you, “This was a terrible mistake.” But you could also raise this counterfactual: “What if the Americans did not get involved and how would it have worked out for Southeast Asia?” Which is, by the way, very nice and prosperous now. All of that is to say that these are hard judgments. Very hard judgments.

Jon Sine: When reading your book, I was thinking that there is a fine line between describing these players battling for prestige and simply narrating that one side actually believed in a domino theory while the other side correctly presumed there was one. Where do you draw the line between objectively analyzing that each side is engaged in this game? Is there a place to step out and say, “You can analyze this correctly but you don’t necessarily need to engage in the game“? I guess it goes beyond the realm of a historian, but it was something I was trying to think about for lessons today. We’re not in any sort of domino theory situation now, but...

Sergey Radchenko: Exactly right. You might ask, “The domino theory — Vietnam was interested in taking over Southeast Asia. So what if they did? Would American global interests still be deeply undermined or fatally eroded somehow?” That is where you have to make the strategic judgment about what’s important and what is not important for America, and what’s worth paying the price for.

We all have to agree that having communists take over Southeast Asia was perhaps not the best idea for freedom and democracy, but is it worth sacrificing all those lives and basically getting America stuck in this quagmire far away from its shores? What would have happened if the Vietnamese were victorious earlier? Would that not have worked out differently?

Perhaps the Vietnamese had so many problems that their hopes to dominate Southeast Asia would have run aground anyway for internal reasons, also because the Chinese would be upset with that as well — as what ultimately happened in the 1970s with the Sino-Vietnamese conflict. Maybe the Americans should not have gotten involved precisely because this was far away from their core interest.

But what about Korea, then? You might come back to Korea and say, “That is also far away from America. Should the Americans have gotten involved, or should they have just followed Dean Acheson’s advice and stuck to their defensive perimeter?” It’s all about strategic judgments.

This matters today as well. Let’s say the Russians overrun Ukraine and establish a puppet regime or annex Ukraine. Would America’s global interests or core national interests be fatally undermined? You can make the argument both ways. You could say yes, because American credibility would be at stake — others will say, “America is a paper tiger, they cannot be trusted, they cannot even defend Ukraine, so how will they defend Taiwan?” and other things start falling apart.

Or you might say, “Actually, it doesn’t really matter.” Ukraine is far away from America’s core interests. America’s core adversary is China, that’s where it should be focused. Some people have been arguing exactly that, and so Ukraine is a distraction.

As a historian, what can I say about this, apart from noting this was always a problem and always part of the discussion? The best we can do really is see how historically things have worked out. Sometimes they have worked out well, and sometimes they have not. But there was always a price to pay. That is a very unsatisfying answer from a historian.

Jon Sine: It’s not unsatisfactory, but I would also draw in the domestic aspect as well. You go to pains to show how much it undermined the Soviets to spend so much of their effort and attention in these Third World competitions that ultimately were of little significance. We still feel the effects in the United States from our voyage into Vietnam in terms of undermining faith in the government. I think that’s another aspect that needs to be considered.

Sergey Radchenko: That’s right. The Soviets were ultimately the losers of the war in Vietnam. You’d think the Americans were the ones who lost out, but as I argue in the book, it’s actually the Soviets who lost out. They thought they won, but what they got was an ally they constantly had to pay for, and that was a gigantic drain on Soviet resources. They just kept paying for the Vietnamese, and the Vietnamese said, “Sorry, you have to forgive all those loans because we cannot do anything.” That actually contributed to Soviet over-extension. Who’s the real winner then? That’s a big question.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s reel it back to the Stalin-Khrushchev transition. I love how you painted how the fight to kick out Beria ended up creating a fork in the road where Germany could have ended up in a different place, but everyone kicking out Beria ended up making that path toxic. What should people reflect on when understanding that power transition?

Sergey Radchenko: That is really an interesting period. We still don’t know all that much about it. We know enough from the memoirs and recollections of people like Nikita Khrushchev about what actually happened. We have the film “The Death of Stalin.” That’s where most students learn about Beria’s demise from.

The problem for that period — late Stalin up to maybe ’53, ’54 — is that we don’t have sufficient documentation. It’s not that it’s unavailable; I think it just doesn’t exist. Things like Politburo records of what they were discussing in the Politburo — the Presidium, as it was called — we don’t have that. There are some gaps in the record.

There is an interesting story about Germany in all of that. Around this time, the Soviets get the idea that East Germany should perhaps not try to build communism. It’s not working out well. They try to communicate that to the East German leaders, who are very hard-line, committed orthodox communists. These leaders keep pushing policies which result in a full-fledged uprising in Berlin in June 1953, which has to be suppressed with tanks, tragically.

The Soviets get this idea of maybe having a confederation or something similar. What they actually say is they could have a bourgeois Germany — a bourgeois Germany that is not aligned to the West necessarily, but is also not a communist country.

Now, the question is who’s pushing this? That becomes difficult to answer because you have people like Beria who seem to be in favor of this. Stalin’s hideous henchman comes across almost as a liberal, letting people out of the Gulag, saying to the Germans, “Look, you don’t need to build communism.” Beria is one. Malenkov seems to be supporting this as well, so it’s very difficult to say that it’s just Beria, because Malenkov also entertained similar ideas.

What I argue in the book is that Beria is arrested, and in the process where they try to implicate him or pin all kinds of terrible things on him, they say, “Well, he’s a Western spy, he’s a British spy. He was trying to undermine communism in Eastern Germany.” This is where internal politics and external foreign policy overlap. At this point, Malenkov could have said, “I also was in favor of the same policy,” but notably, he doesn’t. That’s how it works.

Beria is executed, and East Germany remains basically communist. Later, West Germany becomes admitted to NATO, and at that point, this idea of the neutral Germany that is bourgeois but not aligned to the West falls by the wayside. The Soviets then commit to maintaining the regime in the GDR, which is very costly. It’s a very costly proposition and difficult to do because people keep running away, which is one of the reasons that ultimately they have to build a wall.

What I’m trying to do with this book is show that you can actually have a variety of policies. At different times, like in ’53, they thought, “What about this approach?” It didn’t work out for different reasons, and then a different policy emerged.

Jon Sine: Your research basically finds the same thing as Joseph Torigian, that especially in those moments of transition of leaders, it’s really not about policy discussions at all that determine what’s going on. It’s internal struggling, what he calls a knife fight with weird rules.

Sergey Radchenko: That’s right. Joseph’s book is fantastic on this. In fact, we work from some of the same materials.

That’s what you get. Once you go into the real depth with these records, what you see is really just people above all. You see people positioning for power, for influence, backstabbing each other, and so on. Big questions of policy get drawn into this in weird ways, but sometimes in ways that you would not expect necessarily.

This is something interesting because I don’t know how you would explain that from a theoretical perspective. It doesn’t really work out. Acquaintance with archival materials like Joseph Terian and myself have been able to do is very useful.

Jordan Schneider: It’s like the theory is just schoolyard politics, which is kind of incredible. You have these moments in this book of big statesman-like times where Khrushchev feels really good when he meets with Eisenhower, and Brezhnev feels like he can do business with Nixon. But those are the times where your grasp on power is most secure.

When it’s not secure domestically or internationally, then it becomes about the unseemly parts of human nature that are evolutionarily the things you would see 10,000 years ago, not what you would necessarily expect humanity to be able to pull off and aspire to in the 20th century.

Sergey Radchenko: Jordan, I would actually argue against this. People don’t evolve so fast. In some ways, we do behave like monkeys in the forest because that’s evolutionary behavior, the struggle for “I’m the king of the hill” and “Everybody defer to me.”

If we see that with monkeys, why wouldn’t we expect people to have the same tendencies? Fundamentally, those psychological motivators of human behavior are really important. This is where over-reliance on some grand narratives about ideology or realpolitik starts falling apart. Yes, of course, all of those things matter. But in the end, we are monkeys in the forest.

You see these behaviors historically repeating themselves again and again for centuries. There must be something fundamentally human to this kind of behavior — this struggle for power, struggle for recognition, the desire for legitimacy, the desire for prestige. All of those things seem to be deeply rooted in human psyche.

Jon Sine: Once upon a time, I wrote an essay that I was going to use to get into my PhD program on reorienting how we think about international relations around these Evolutionary Psychology ideas of status and prestige. Needless to say, I’m a fan of your narrative.

But you can also root it in something else — philosophy, or at least great works of art, which you do. You quote from Dostoevsky in describing, I think it really applies most of all to Khrushchev above anybody else, “Am I a trembling creature, or do I have the right?” That just jumps out at you as something correct when you look at Khrushchev.

Maybe let’s fast-forward to the Stalin speech because in a way, he’s not so much a trembling creature when he’s up there thoroughly denouncing Stalin. This will be the thing that he’s known for. You look at some of the Marxist historians who say after reading “China Today,” this is where they say it all started to go wrong. Tell us about that.

Sergey Radchenko: Khrushchev decides to denounce Stalin — this is known as the Secret Speech — denounced Stalin for his various crimes, for repressions, for the way that he conducted the Second World War. The party is absolutely shocked. When this verdict is delivered, the party faithful are there, and they cannot believe it. Although for a time, things were kind of going in that direction anyway, so you had silent de-Stalinization already shortly after Stalin’s death. But in February 1956, it becomes official. It’s not publicly announced because it’s a Secret Speech, but it’s circulated inside the party.

It’s a very interesting question as to why Khrushchev does that. When you read about this, you almost feel sympathy for Khrushchev. You think, “Well, here’s a good guy.” But then you also have to remember that he did all kinds of other things, like ordering the Soviet invasion of Hungary, which serves as a counterbalance to this very positive view of Khrushchev.

Why did he do that? Was it for political reasons in order to consolidate his power, or did he really think that Stalin was a terrible person? I think probably both. It helped him consolidate his power, but there’s no reason to think that he was lying when he was saying that Stalin was a criminal.

Now, some people said, “Well, where were you? You were also participating in all this stuff. You benefited from this because your career overlapped with absolutely horrendous purges. You built your career on the bones and blood of your predecessors.” There’s something to that as well.

But when all is said and done, you look at this Secret Speech of February 1956, you cannot help but feel that this was the right thing to do. You cannot help but feel like this is one of the good moments for Khrushchev. There are some others, like the way he decided to back out from the Cuban Missile Crisis, where you feel, “He did the right thing.” That’s how I felt when I was looking at it.

But the Chinese were not very happy. Mao Zedong was saying, “Wait a second. You did not consult us.” This is part of the problem. Mao Zedong himself did not like Stalin, but he certainly did not like being surprised like that by Khrushchev. He said that, “Stalin was a great sword, and Khrushchev had discarded the sword, and now our enemies will seize it and try to kill us,” or as he would also say, “Stalin was a great rock, and Khrushchev lifted it only to drop it on his own feet.“

Mao predicted problems for the communist movement, and of course he was right because problems broke out in places like Poland that summer of ’56. Then ultimately, in the fall of 1956, we had the situation in Hungary that just went off the rails very quickly. All of that is connected to de-Stalinization.

In my book, I talk at length about it. I don’t focus so much on the domestic impact of de-Stalinization. There are other people who have written fantastic books about it, but what I look at is how it impacted countries like Poland, Hungary, North Korea, and then I also talk about China’s role in all of that.

This is where Mao Zedong, for once, feels like he’s the great strategist who’s determining the fate of global communism because he sends a delegation to Moscow led by Liu Shaoqi. Liu Shaoqi says in conversations with Khrushchev, “What you’re doing to Poland, trying to pressure Poland — this is called great power chauvinism. You should stop doing that. On the other hand, in Hungary, that is a kind of revolutionary rebellion, so you should basically suppress that.“

e know there is no Soviet intervention in Poland, and there is Soviet intervention in Hungary — by the way, for reasons that had nothing to do with Liu Shaoqi’s advice. It was for Khrushchev’s own reasons that simply overlapped with what Liu Shaoqi was saying. But the Chinese conclude that this is because of their advice. So they have finally got to a position where they’re determining the general line of the communist world movement, and that, I think, is consequential for the Sino-Soviet split, for all the things that happened afterwards.

Jordan Schneider: Two quotes, some of my favorite from the book, where you found in the Politburo that Mao talked about Khrushchev’s Stalin speech as if Khrushchev had broken the incantation of the golden hoop. Of course, the brocade that the Monkey King wore and now everything’s going to go crazy and Mao’s going to be able to be free. The superstitions of what can and can’t be done to challenge the Soviet Union are now blown wide open.

I also love the detour that you had of these incredible sources of the pro-Stalinist folks in Denmark and Norway. The story’s been told a lot in the US, but at some point, I think it was the Danish guy who was so pissed off — when he was getting the readout, he was saying, “Khrushchev, what were you doing? You should’ve arrested this man, Stalin. What a monster.“

The ability for some folks to see through the cognitive dissonance of it and say, “Okay, we should just give up. This is a completely bankrupt thing.” And then other folks in different situations are more or less bought into the system, or their incentives are different. It’s funny that the players with the least actual political power, the intellectuals in the West, were often the ones who clicked most quickly to the fact that a communist system able to bring about someone like Stalin is just a bankrupt endeavor on its face.

Sergey Radchenko: It took a while actually, and obviously ‘56 had a dramatic impact on the world communist movement. In many ways I would say 1956 was the beginning of the end for communism.

It was very clear. If you needed to use tanks to suppress a country or to promote your vision of economic development, you’ve got a problem. That is where you have a collapse of party memberships in communist parties across Western Europe. So many things can be linked back to 1956.

It was such an eye-opening moment for Western intellectuals, many of whom just could not believe that Stalin could be such a hideous figure. But that’s a consistent problem. I was struck reading Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird’s biography of Oppenheimer, American Prometheus, where they discuss how nuclear scientists working out in California were just absolutely blind to the brutalities of the Soviet system. You think, “How can smart people who are obviously geniuses in physics be so uncritical as to think that there’s this worker’s paradise and everything is going wonderfully well?“

For Oppenheimer himself, 1939 seems to have been the turning point — the Soviet-Nazi pact. After that, he finally started thinking that perhaps this Stalinist paradise was not so wonderful after all. But Soviet intellectuals continued to believe until 1956.

In 1956 you have the double shock. First, Khrushchev himself says, “Look, Stalin is not the father of humankind, not this great genius or demigod that we held him for, but actually a brutal criminal who repressed innocent people and was just a terrible person.” Then you’ve got the Soviet intervention in Hungary which nails the final nail in the coffin of the Soviet project for many Western intellectuals. That’s why you have this chaos in Western European Communist Parties from CPUSA to the Norwegians, the Danes, Great Britain, and so on.

Jon Sine: You just said in 1956 you could see the beginning of the end of communism. When Deng Xiaoping was writing at the Sixth Party Plenum in 1981, rewriting the history of what happened in China, he’s very careful not to reject Mao in total, seeming to draw a lesson from 1956.

This is a very prominent lesson today among certain Marxist historians who look back at the Soviet Union and how it fell. 1956 is a crucial year, but you didn’t just root it in the Secret Speech. You pointed to tanks going into Hungary as a crucial thing. Do you agree with their analysis? Was there a way to save Stalin’s reputation? Did the Chinese keep a 70/30 Stalin type of interpretation? What are your thoughts on that?

Sergey Radchenko: That’s obviously how Mao would have liked to see things, which is why he proposed to discuss Stalin in those terms. That Stalin committed some mistakes — mainly not believing in the revolution in China and mistreating Mao. But generally speaking, he was a great Marxist-Leninist. That would have been a better approach.

Stalin was a horrible person, and saying this frankly and openly was a better thing to do. In fact, the problem with the Soviet Union and with Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization was that they did not go deep enough. They deposed Stalin but the system remained, and I would argue the system still remains. Is that a good thing? I don’t think so.

There needs to be a different approach to people like Stalin in places like Russia and to people like Mao Zedong in places like China. But of course the Chinese will say, “We are careful. We don’t want to undermine the legitimacy of the communist state. That’s why we still print Mao Zedong on our money and that’s why his portrait hangs over Tiananmen Square, because he is the founder of the Chinese state. If you say that he was a horrible criminal responsible for the deaths of 35 million people, well... that might delegitimize the Communist Party.” Are they wrong? I think they’re probably right — of course it will delegitimize the Communist Party.

Jon Sine: Nothing delegitimized the Soviet Communist Party more though than their failing economy. You mentioned not de-Stalinizing. There was the Kosygin reform which could have radically restructured, gotten rid of the ministerial planning apparatus. I feel like if they were going to go down that route, they needed to get away from the Stalinist planning system at some point. It could take you to maybe the early modernization, but they never seemed to get out from under it.

Sergey Radchenko: Khrushchev’s reforms brought about a lot of chaos in the USSR. Constant restructuring, compressing ministries, taking out whole parts of the apparatus. I say in the book that Khrushchev was like this guy who felt the communist project was a really great project and you just have to tinker with it here and there. Take out a pin here, put something there and then it would work just fine. The problem was that it fundamentally wasn’t working, so that realization took some more time to creep in. That’s already after Khrushchev.

We can see the key point, as you rightly pointed out, is that the Soviet project was not delivering for the Soviet people. It was not delivering enough because the Soviets set themselves up not just with the claim that they would improve the standard of living — because actually the standard of living was improving — but that they would outstrip the United States.

They claimed they would be better. We have the kitchen debate, that famous encounter between Nikita Khrushchev and Richard Nixon, of which we have a video recording. I was so happy to find the Soviet version of it in the Russian archives, which was hilarious to see what was not captured on tape. They go around and Nixon shows this and that and says, “Well, look, this is an American house.” And Khrushchev responds, “No, this is made of wood. This is rubbish. We now make stuff of plastic. This is so much better.“

You have this competition with the United States. The idea was that it would deliver for the Soviet people and it simply wasn’t doing that. In some areas, there were breakthroughs, but by and large, the Soviets had meat riots. Think of the 1962 riot in Novocherkassk where the KGB had to be deployed — the military police — to break up a protest with casualties. In 1963, the Soviets were spending their gold reserves to import grain for the first time. That is already where you’ve got some serious warning signals coming.

That’s why they launched the Kosygin reforms. But then that kind of goes off the rails. At the same time as all these problems in the economy multiply, they also discover oil and gas in much larger quantities in western Siberia and they think, “Okay, that will save us.” To a certain extent it actually helped them for another decade or so but ultimately, of course, the whole thing fell apart.

Jordan Schneider: I want to back up because I don’t want to move too quickly past the second half of the 1950s. You actually have this incredible moment of optimism with Khrushchev, where you have Sputnik, of course, and then this techno-utopian vision that Khrushchev has. He believed that in the future, the Soviets would have a bright future, a fairytale-like socialist abundance with people having so much to eat that they would, quote, “be careful not to overwork their stomachs” as robots did all the work. People would just hang out, only working for an hour or two per day.

You make this fascinating connection between what Sputnik does and how it changes Khrushchev’s psychology, leading to some of the most dangerous moments in human history. Could you explain that connection? Khrushchev has this big technological breakthrough, decides he’s going to catch up and surpass the US in 15 years, and what does that lead to in terms of the risk of war in various hotspots around the world?

Sergey Radchenko: As you say, Jordan, these are interrelated processes. The Soviet defense program, the missile program, and the Sputnik program were obviously intricately related. In fact, Sputnik was launched on an ICBM.

What was happening in terms of defense priorities? The Soviets got their bomb in 1949, still under Stalin. There was a modest buildup of nuclear bombs in 1950, but then they really put a lot of effort into the development of missile technology. By around 1955, there were some serious breakthroughs.

First, you had a proper Soviet thermonuclear test — not the one in ’53, which wasn’t the later design — but the proper thermonuclear test in 1955. That made Soviet nuclear weapons much more powerful, giving Khrushchev this sense of great power: “Look, we’ve got these massive weapons that can destroy whole cities.” That was an empowering feeling.

Then you had breakthroughs in missile technology. By 1956-57, missiles increased their range. In 1957, the Soviets conducted the first test of an ICBM — intercontinental ballistic missile. Khrushchev realized this basically meant the Soviet Union was invincible as a power. It could reach the United States. It could destroy the United States.

For the first time, he developed this feeling — later shared by all Soviet leaders and even today by Russian leaders — that Russia was a mighty power precisely because it could destroy the world. That’s where its claim to greatness came from. It could destroy the world, and nobody could mess with it. For the first time, Russia could be safe because nobody would dare to invade a nuclear power.

Khrushchev understood that, which is why he began massive cuts in the armed forces and shut down projects like the battleship program that was Stalin’s prestige project. Why? Because he believed in nuclear weapons. He felt they gave the Soviets might and a new voice in international politics.

Although he didn’t plan to use nuclear weapons, he used them for blackmail and discovered the usefulness of that already in 1956. During the Suez Crisis, Khrushchev threatened to destroy Great Britain and France. Those powers ultimately backed out from Suez for reasons that had little to do with Khrushchev’s threats — mainly American pressure on the British. But that’s not what Khrushchev thought. He believed, “I was so successful in doing that. Now, let’s play this card again and again.“

That, Jordan, got him into dangerous situations, ultimately leading to the Cuban Missile Crisis, because he felt that the Americans or anybody else would have to retreat when faced with Soviet might. It gave him this trump card to play.

On the Sputnik side, you had the launch on October 4th, 1957. That’s why we talk about the “Sputnik moment” — a term we now use to describe breakthroughs by America’s adversaries. The original Sputnik moment was a great breakthrough which symbolically showed that the Soviet Union could outcompete the United States in a key area of science and technology.

Unfortunately for the Soviets, they weren’t able to capitalize on this. Though they could capitalize on Sputnik itself, they couldn’t provide sufficient investments in scientific and technological terms into their own economy where their economy would compete with the United States. There were structural problems with the economy as well, and it simply wasn’t competitive.

The Sputnik moment faded away fairly quickly, but what remained was the Soviet nuclear threat, which was real and which became ever more serious as time proceeded.

Jon Sine: The Cuban missile crisis remains one of the most hotly debated historical occurrences. From the US perspective, it’s incredibly important. The Sputnik moment you mentioned factors into that. Another element is the menage a trios between China, the US, and Soviet Union — a constellation of powers competing for greatness.

The Soviets seemed to have a trickier game to play because they were balancing their great power aspirations between themselves and the US while also competing for leadership over the communist revolutionary world with China. They were attempting this double dance, which came to a very dangerous head in the Cuban missile crisis, with that process playing into Khrushchev’s decision to try to win over Fidel Castro.

How does bringing in the Chinese and the competition for prestige dynamic change how we think about the Cuban Missile Crisis?

Sergey Radchenko: That’s a great question. The Cuban Missile Crisis is a very overstudied episode of the Cold War. What I contribute in my analysis is precisely this Chinese angle, which is fascinating. We haven’t really been talking enough about that.

If you think about the Cuban Missile Crisis, what questions are we still trying to answer? The first question is why Khrushchev sent missiles to Cuba in the first place. There are different competing theories about it.

The prevailing American theory for years was that it was strategically necessary for the Soviet Union. Khrushchev realized that his ICBMs — for all the Sputniks of the world — weren’t particularly good. They weren’t accurate; they were problematic. So he had to put intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Cuba to target America more accurately and reliably.

That has been the traditional explanation for Khrushchev’s decision. Looking at the Soviet and Russian records, there isn’t a single moment where Khrushchev actually raises this as an explanation — not once. I didn’t find a single piece of evidence to support that. It’s more about political scientists trying to figure out why Khrushchev would do this than Khrushchev actually explaining his reasoning.

In the 1990s, Sergey Mikoyan, who was the son of Anastas Mikoyan whom I previously mentioned, proposed a different theory. He suggested it wasn’t about addressing strategic problems at all. It was about saving Cuba because of the Bay of Pigs and the fear that the Americans would take over Cuba — a realistic fear, let’s be honest. Khrushchev wanted to save Cuba.

Is there evidence for this? If you look at the Russian records, including the Presidium discussions, you actually find evidence for it. Khrushchev says on at least two occasions, “We just wanted to save Cuba from American invasion.” This is very interesting because it supports this particular theory.

In my analysis, I ask why he was so obsessed with Cuba. What was that about? I argue that it was because he was in competition with China, where the Chinese were saying, “The Soviets have betrayed revolution. They’re weak. They’re not standing up to American imperialists.” Under those circumstances, losing Cuba — which was basically a socialist country run by a real revolutionary, a wannabe communist — would be unacceptable to Khrushchev.

He was really worried about the Chinese angle. There’s substantial evidence for this because throughout and after the crisis, he was very sensitive to Chinese criticism. He kept telling the Cubans, “Don’t believe the Chinese. We don’t want to sell you out. We are actually the only ones helping you,” and “Look what the Chinese haven’t done for you anyway.“

The Chinese had made their own inroads into Cuba because they were talking to Che Guevara, who had a very close relationship with the Chinese ambassador. This presented a big challenge for Khrushchev.

Bringing us back to the angle about prestige and the Soviet desire for recognition and greatness, there’s another interesting piece of evidence that connects to my theory. Khrushchev wanted to be treated as an equal to the United States. When he was making the decision to send missiles, it was in the context of a discussion about American missiles in Turkey.

From his position, if the Americans had nuclear Jupiter missiles located in Turkey, why couldn’t the Soviets have missiles in Cuba? That wasn’t fair. Khrushchev commented, “We will effectively give the Americans a little of their own medicine.“

If you psychoanalyze this phrase, what does it mean? Does it mean he was really concerned about strategic problems or reliably hitting Washington? He never wanted to use nuclear weapons to begin with. No, it was more about equality — why were the Americans allowed to have missiles near Soviet borders, but the Soviets weren’t allowed to do the same? This brings in the question of equality, status, and greatness: “We are on par with the United States. We can destroy them, therefore they should not expect special treatment.“

That’s how I describe the opening phase of the crisis. The relevant chapter also discusses how the crisis itself unfolded. I was fortunate to have access to remarkable materials that add to our understanding of how Khrushchev ultimately decided to back out from the situation.

The key piece of evidence is that Khrushchev really thought Castro was going off the rails at one point, especially after Castro proposed to nuke the United States in a first strike. Castro later denied this, saying he never meant anything like that, but that’s how Khrushchev understood Castro at the time. Khrushchev was shocked, thinking, “What is he talking about? This guy’s crazy.” At this point, Khrushchev became frightened.

One of the things you find in the Russian archives is how early Khrushchev decided to back out. Kennedy gave the quarantine speech on October 22nd, 1962, and then Khrushchev dictated a letter to Kennedy on October 25th, already effectively backing out of the crisis. It only really lasted for three days.

Analyzing Khrushchev’s language and concerns is fascinating. All of that material is now available in Moscow for researchers — though I don’t recommend going there.

Jordan Schneider: The dynamic you see in the Cuban Missile Crisis is one that plays out over many crises, where we have lots of influential actors say, “Let’s just send some nukes. It’s the path of least resistance. It’ll solve our problem.” We mentioned this earlier in the Korean War context, and it happened here as well.