TikTok Ban — Is Congress For Real?

What happens next with the app

This week, the US House of Representatives voted in favor of a bill that would force ByteDance to sell off TikTok to a firm not based in a country designated as a foreign adversary, or effectively cease operation in the US in 180 days.

To discuss the US domestic politics of the dramatic rollout and broader social, national, and geopolitical implications, we interviewed Ben Smith of Semafor to the show.

We get into:

Whether or not TikTok has already engaged in political manipulation;

Arguments against the ban, from critics on the left and the right;

The political economy factors that led to swift and bipartisan passage in the House;

What this means in an election year.

A Threat (?) to National Security

Jordan Schneider: Ben, thank you for coming on such short notice.

I did a show with Kevin Xu in March a year ago, after the TikTok CEO testified — which was a disaster. We had the RESTRICT Act come out of Senator Warner, which went nowhere.

Things were quiet until last week, March 5: Representatives Gallagher and Krishnamoorthi out of the House China Committee came out with a bipartisan bill, which lays out a framework establishing that Apple, Google, and other platforms are banned from doing business with big social media apps headquartered in a foreign-adversary nation — those being China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran. The bill gives a 180-day window for divestment.

We had a 50-0 vote out of Committee, and then a really strong bipartisan vote on the floor of the House. The bill is going to the Senate, and Biden has already said that he will sign it if it passes.

Ben Smith: It’s a really unusual situation. I think I would just say that one thing that I would note that also happened today: the British government moved in a very swift unilateral way — which is something the British government can do that our government cannot — to block an Abu Dhabi–based investment fund from buying The Telegraph. In some ways, that comes from the same impulse. This is another Western democracy saying that we can’t necessarily just let anybody come into this country and speak.

Jordan Schneider: I want to bring this back to January of 2019. I’m a grad student in Beijing, and the first article that I wrote — which I pitched to James Palmer at Foreign Policy — is a piece that I ended up publishing anonymously, basically laying out the argument that TikTok is a problem. I’m pretty sure this is the first piece on the internet laying out the case — so this has been surreal to see everyone who isn’t far left or far right concurring with the central points of that argument.

Here’s a quote from the piece:

The potential for Chinese government interference in ByteDance is considerable — and like other tech firms in China, there’s little the company can do about it. At some point, the Chinese government will realize the potential impact content platforms like ByteDance have on foreign public opinion. In such an eventuality, Russians spending a few million dollars on social media ads in the 2016 election will seem like child’s play compared to the Chinese government compelling TikTok to tweak its algorithm to boost certain candidates’ chances.

Chinese tech firms are not enthusiastic partners of these sorts of foreign policy endeavors. ByteDance’s CEO is surely not happy to issue apology letters and face mandated shutdowns of popular products. But at the end of the day, there is very little that these firms can do in a party-state environment.

Ben, what are your reflections on how the media and politicians digested what TikTok potentially meant to the body politic?

Ben Smith: You were very prescient back as a rookie journalist in 2019! That seems like 10,000 years ago on this story. But that was also a moment when TikTok was entering the social-media wars. Big arguments over Facebook, in particular, had wracked American politics.

TikTok isn’t exactly social media like that. It’s a different thing. It’s a video consumption app. It has some social qualities, but it’s not really a social-media app. The US — unlike Europe — has totally failed to put in place any data-privacy regulation, or any kind of age-gating for all these other apps.

As TikTok became the most popular entertainment app in the country, there was an obvious reflex to say, “We should apply these things to TikTok; because it’s Chinese-owned, that makes the data-privacy stuff extra scary.”

That’s not a total red herring — but it’s also true that because TikTok is not a social network. The information the operators get from it is much more limited than Facebook. You don’t see people’s social networks. There’s information that you can buy in the open market about any particular person that is much more detailed and identifying.

The obvious response to that argument — about TikTok being a Chinese state-governed company that could potentially use you to exercise political influence — is that this is a latent threat. But there’s not a lot of evidence they’ve done it. That is really worth saying out loud.

Actually, the most compelling evidence that it could really be used as a direct political tool in American politics came last week when they mobilized their user base to fight this bill. The people at TikTok continue to think that blast was a great idea which showed lawmakers how much power they have. I really think it deeply backfired, and it showed lawmakers how much power they have, and how much power the Chinese government has in a direct way to influence American politics. Even though, of course, it is this business fighting for its life.

But it was just this huge flex of muscle. Because a lot of lawmakers who originally just thought, “This is just an app where kids dance, it’s just shows like weird four-second clips of strawberries” — when the people who run TikTok say, “Okay, time to intervene in American politics,” and lawmakers are getting these phone calls from eleven-year-olds with the school bell ringing in the background saying they’re going to kill themselves if TikTok is taken away … that snapped Congress into a bipartisan movement toward banning it, and it just sailed through the House.

Jordan Schneider: As far as the threat being latent — I feel there was enough of a track record over the past few years that demonstrates that stuff wasn’t entirely clean. When you searched Houston Rockets, you wouldn’t find anything.

Interestingly, I think the turning point was actually Black Lives Matter. Because in 2020, before Black Lives Matter, they really had this vision that this could be a non-political home for like funny entertainment videos.

And what happened was, at the start of Black Lives Matter, TikTok decided — or the algorithm decided, or whatever — that this conversation is too political, so we don’t want it to be happening. Videos where people talked about George Floyd and police violence didn’t get hits or got shadow-banned. Very quickly, that became a news story. That kind of censorship is something that is untenable to have in the US.

So, from that point on, you were able to have political speech on TikTok — and it was able to go viral and blow up. And once it’s there, the latent-ness becomes very clear. And then they literally did the thing that everyone was worried that they would one day do — targeting specific districts and finding people who they thought would be sympathetic, and giving them push notifications saying, “Call your senator to lobby for this thing”; that’s just not something they can get away with.

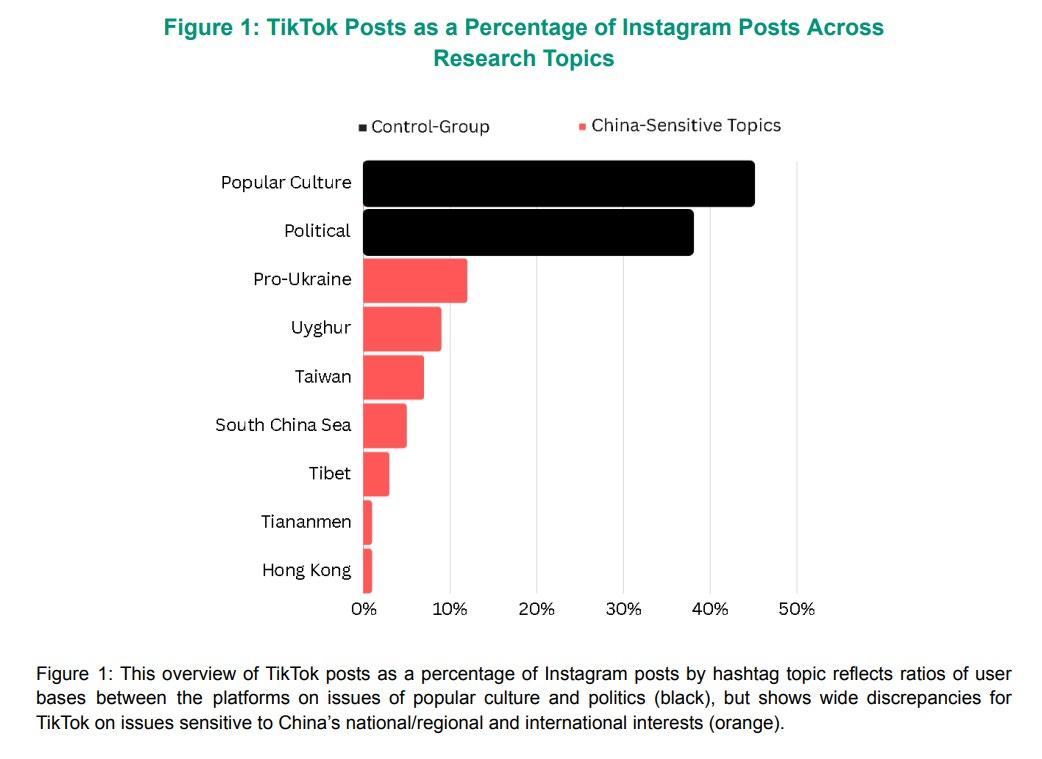

Ben Smith: There was also a time when you couldn’t search Uyghur stuff — but I don’t know, when I last looked at the app, the fifth video I was served was, “I’m Uyghur, so of course I look like this and talk like this,” in a very normal TikTok way. [Jordan: see the chart above…]

And when you say that there have been instances of them using it for large-scale political sort of manipulation: I actually don’t think that’s really been established, except for this one vote.

I do think, though, what we’ve been talking about is content-neutral. The huge shift in youth culture against Israel and toward Palestine was not a product of TikTok, but probably was amplified and powered by TikTok. That stance is not where the mainstream of American politics is, and a lot of legislators really hated that. One of the reasons some want to ban it is because they see it as anti-Israel.

I think this is where the First Amendment considerations are coming from. Certainly on the Hill, that’s part of what made people hate TikTok, just no doubt. I don’t think it’s part of the legal argument, but it does underlie the momentum.

Jordan Schneider: Well, it’s possible that pro-Palestine amplification is because that stance happens to line up with a Chinese policy priority, which is something that we’ve covered.

Ben Smith: Right, exactly — but there isn’t a smoking gun.

Free-Speech Objections and the Trump Factor

Jordan Schneider: Speaking of a latent political ticking time bomb — 180 days from today is September 7. If you’re President Biden, do you want this to wrap up before the election or after the election?

Ben Smith: There is zero chance that this wraps up before the election. I think people just need to like take a breath and realize that. The Senate is not going to pass it tomorrow — and even if the Senate passed it tomorrow, it would still be in court when the election comes. There are going to be very, very serious legal challenges to this.

Jordan Schneider: If you have TikTok with a gun to its head, doesn’t that make it an even more tempting thing to potentially invoke political manipulation if their only way to survive is via a Trump victory?

Ben Smith: I don’t think so. The propaganda victory of them forcing the US government to shut this app down that lots of people love is its own reward. But who knows: maybe on the last day of TikTok, they’re just going to broadcast Xi’s face deepfaked over Barack Obama speeches or something.

But one detail that I do think is interesting — TikTok has peaked. DAUs are flatlining. It was a huge cultural trend two years ago. It was a big thing last year. These things come and go — and so of course, just the nature of Congress and of our culture, we’re having this argument as TikTok continues its long, inevitable slide toward becoming Vine.

I was trying to explain this story to my fourteen-year-old, and he was like, “Nobody uses TikTok anymore. What are you talking about? We’re all on Instagram.”

Jordan Schneider: There’s no way China would approve a deal. The investor base is 60% foreign money. That foreign money is like SIG, Carlyle, Fidelity, General Atlantic, Tiger Global, and SoftBank.

Then the Chinese money is not Chinese deep state, like Xi-family adjacent. We’re talking about funding from places like GGV, Primavera, Source Code, and Qiming. The CEO was a liberal after all. This is a company that is not developing core hardware.

Ben Smith: You don’t think the Chinese government is going to have any compunction about screwing ByteDance?

I mean, the stakes from their perspective are actually pretty low, right? They might lose this potential future propaganda tool, ByteDance stock goes up, stock goes down — but because at some level the Musical.ly acquisition years ago sailed through, and TikTok grew to this scale without intervention, this is now so much a US problem. And it’s something that they can torture the US with — but it’s not massively their problem, right?

Jordan Schneider: I just don’t think it’s a story once it gets banned.

Tianyu Fang, a Stanford student, wrote a piece on this recently. His line was, “The TikTok ban will seemingly legitimize the Chinese model of internet governance, which sees foreign platforms as inherent threats to political stability.” I think it’s worth taking that argument seriously — but in the world we live in now, I don’t know how you run the clock back to the internet of the 1990s or 2000s.

Ben Smith: It does reflect a real lack of internal confidence in the United States and in Britain right now — that our system is so obviously superior that we can withstand some communist speech, and that our kids aren’t all going to go become communists because some silly app is telling them to.

People in the US now do not think that our system can withstand some propaganda and feel like, “Maybe our system can’t withstand some propaganda, and we need to ban it.” I mean, they may be right. I’m not saying that’s the wrong view — but it does reflect, I think, a real deep insecurity about the American system in a very big-picture way.

Jordan Schneider: Another excerpt from Tianyu, this one co-authored with Tim Huang:

We need greater faith in the innovative capacity of US technologists and startups and in the vitality of American soft power in the form of its cultural output on every platform. We need to think about how to unleash those assets, rather than understanding US-China competition in purely defensive terms. The path to winning is not to ban TikTok, but to out-compete it.

Where do I disagree with that? Doing export controls on semiconductors and banning TikTok both need to happen — but the way you win a long-term national competition is not by restricting market access to stuff. It’s by growing faster, innovating more, and developing a healthy, resilient polity.

Ben Smith: Well, you will be glad to know that America’s greatest innovator, Mark Zuckerberg, has cloned TikTok’s most powerful features, created a system for ripping off specific TikToks and importing them into Reels, and leveraged Instagram’s existing social features to make it stickier than TikTok. And he’s winning!

Jordan Schneider: Sure. The one that I think is going to be the more dramatic long-term consequences is what the world is going to do about Chinese electric vehicles. Because unlike TikTok, these things are actually twice as good and half the price. You had this new ICTS regulation, which came out two weeks ago, which to me looks like the first step in banning Chinese electric vehicles in America.

Ben Smith: Do you think of this as a sort of issue of protecting our domestic industry, or of worries about espionage?

Jordan Schneider: Well, the stated concern is espionage. I am not worried about Google and Facebook needing competition. Ford and GM, though, I think do need competition. This case is way more embarrassing and reflective of a mindset among old companies that haven’t figured out how to compete in the twenty-first century. They feel that, absent protectionism, they won’t be able to compete in the US and European markets.

Ben Smith: So you think this is a dress rehearsal for higher-stakes fights down the road?

Jordan Schneider: I don’t want to call the banning stuff a sideshow, because I do think that there are certain things that you would just rather not be running around.

Ben Smith: Anyway, anything else you want to ban? Just while we’re banning stuff.

Jordan Schneider: I’m okay for now. I kind of want to watch Ford and GM sweat a little bit. I think they need that. Tesla, Mercedes, BMW, Fiat — I mean, these guys have got to wake up. The cheapest Tesla car is $45,000?

Ben Smith: No, no, the price is dropping.

Jordan Schneider: BYD is making EVs for $10,000!

Ben Smith: Have you driven any of the BYD cars?

Jordan Schneider: I’ve watched a lot of BiliBili reviews, and I want a test drive. BYD, fly me out!

Ben Smith: Ha! Would you take Chinese sponsorship for ChinaTalk

Jordan Schneider: No, I wouldn’t.

Anyways — do you have a take on this Matt Gaetz-AOC alliance?

Ben Smith: You really see in this — and actually in the Ukraine/Israel fights on the Hill— that there is still the shadow skeleton of a bipartisan establishment.

But you have pretty substantial fringes that take differing views: they are isolationist on foreign policy and radically libertarian and worried about government control on this issue.

There are lots of people who would like to ban extreme speech on social-media apps, and the people who are committing extreme speech on social-media apps are often friends of members of Congress and allies of members of Congress and do not want to be banned.

And I think people like Elon Musk see any government intervention to limit anything that their far-right, sometimes Nazi friends might be next, and they don’t want to see that. Or more reasonably, you are just obviously giving the government new tools to control speech and that could obviously be used in all sorts of other ways.

Maybe that’s a slippery-slope.

Jordan Schneider: Do you think Trump is going to flip?

Ben Smith: Trump doesn’t want Biden to have any victories. Trump tried to ban TikTok, and was widely mocked and reviled by people who now support it. I think his basic agenda is to give Biden no wins, to block everything, and to get his supporters on the Hill to block everything.

I do think if Biden bans it, Trump will say it’s the dumbest thing ever — and then claim he is actually the candidate who speaks for the youth. But I would not say these are deeply held beliefs. The Senate is a complicated place.

Jordan Schneider: So is Biden going to come out in favor of national marijuana legalization as a way to win back the voters he lost from banning TikTok?

Ben Smith: I’m skeptical that people who watch creators they love on the internet really feel strongly about the company — whether it’s YouTube or TikTok or Reels. People are just going to move over to another platform and watch the same stuff. Their primary allegiance isn’t to the platform — it’s to the people they follow. I think you saw in India, when they banned TikTok, it just kind of went away and was replaced by clones.

Jordan Schneider: What can you say about the administration’s politics on this?

Ben Smith: Obviously Biden supports it — it doesn’t seem like it’s the thing he wants to talk most about every day. But he is behind the bill, and they’re lobbying for it. But as far as what Biden is saying to Chuck Schumer, I don’t know.

The core decisionmaker here will be the Senate Majority Leader. And when I asked one of his aides about it tonight, they said, “Well, he’s listening — he likes to listen to the caucus.”

He’s hearing lots of different input. Elizabeth Warren wants to do it her way with a different bill. Mark Warner, who’s a very influential figure, supports this, and that’s actually quite meaningful in terms of the Senate politics of it.

But Maria Cantwell, who is also quite important, seems to be on the fence. Schumer could easily just run out the clock on it if he wants, without ever implicating Biden in killing it.

Jordan Schneider: I think the vision that Warner and other sort of national-security-minded senators had was: we could use this TikTok issue to solve a lot of other things — we could take the momentum we have here in order to create a regulatory superstructure that deals with data concerns more broadly. Maybe they would want something that could deal with the EV situation like we discussed earlier.

And that didn’t work. It was really interesting watching Warner come out in favor of the bill, because that’s the same thing as throwing in the towel for the big one. It seems that he’s saying, “Look, if this is all we can get, let’s cash in our chips.”

Cantwell seems to like doing these big bills that don’t go anywhere. To what extent will these people not feel like it’s a victory worth supporting and instead just prioritize their own big thing that only has a 5% chance of passage?

Ben Smith: With Cantwell, it’s not just big things. It’s things her constituents care about. You and I worry about the latent threat of Chinese political manipulation, but every parent worries about their daughter’s self-image and about kids getting drawn into extreme politics and so on with these social-media apps.

To me, one of the most interesting things in the TikTok hearing that wasn’t remarked on so much: obviously a lot of the questions were the partisan stuff you’d expect, but there was a thread of questioning that was basically, “I’m told that you have a sister app in China. But on that app, there’s no violence, there’s no sex, there’s no cursing, there’s nothing unwholesome. Why is the American version so terrible and bad for kids when it’s so wholesome in China?”

Of course, the answer is that it’s an authoritarian state with a very intense censorship regime, and the USA is not.

You could say that this shows an interest in Chinese-style governance from these members of Congress. In the real world of their lives serving their constituents, they are on a quest to do things that they can run for re-election on.

“We protected your kids from social media” is important and powerful. The message that “we did something about Chinese influence” — sure, that could be accessed with this bill or some other bill where they could say the same thing. But they don’t have moms in their district freaking out about China the way they freak out about social media.

Jordan Schneider: In China, there are limits within these apps regarding how many minutes per day you can use the apps, how many minutes a day you can play video games, and the hours in which you can play video games if you’re under eighteen.

Maybe you could circumvent those rules if you get ahold of your older brother’s ID card or whatever. Well, not a lot of kids have older brothers…

I think there’s just a different expectation in most corners of modern Chinese society now that it’s government’s role to play a part in this.

Anyway, on the one hand, you just riffed on the Matt Gaetz-es of the world who say, “Oh, this is government overreach. This should be the parents’ job.” But on the other hand, there is a real mainstream belief that this technology is too dangerous and that we, as parents, need help.

Ben Smith: But this is actual, real politics. A lot of this other stuff is more like Twitter shadowboxing with conspiracy theories about government control or Chinese intervention. Those concerns may be legitimate, but it’s really not what these members of Congress hear about when they go into their districts.

But when they go into their districts and they talk about how they’re going to protect your kids from Instagram, that is actually a very powerful message.

Generational Paranoia or Unprecedented Danger?

Lawmakers are getting these phone calls from eleven-year-olds with the school bell ringing in the background, saying they’re going to kill themselves if TikTok is taken away.

Jordan Schneider: As a media historian, what’s your angle on the political economy of that narrative? Historically, we had similar freak-outs about rap music and violent video games. Is this different?

Ben Smith: I am a media historian, and I have two teenagers and a kid who just turned 20 — and I just don’t know. In every generation, parents freak out about the media the kids are consuming. When we were kids it was a concern about magazines damaging girls’ self images, propagating anorexia and bulimia and waifish models creating this really unhealthy culture — that was seen as a media phenomenon, and as a hugely important social problem that drove depression and eating disorders.

There was panic over Elvis, too, a couple of generations earlier — they set the law after him because he was sexualizing the music in a way that was also crossing racial lines. It’s particularly hard when you’re a parent to actually step out of that.

It’s always hard to be a teenager. There’s that statistic about how few friends teenagers have now and how little sex they have. And I don’t know, I find it actually very, very hard to disentangle. I think there’s a lot of glib social science that like tells people exactly what they want to hear. I don’t feel like I really know.

To close, here’s an excerpt of the podcast we did with Kevin Xu about the TikTok hearings. You can read the full article here.

TikTok Hearing: The End of an Era

Jordan Schneider: I moved to China in 2017. Xi had just changed the constitution, and dark clouds were on the horizon. But even then, there was still this vision that maybe interconnected commercial and technological interaction between China and the rest of the world could potentially build the context in which the US and China could relate to each other on better terms. This hearing and the RESTRICT Act really marked, to me, the end of an era.

The consensus that has been manifested with this bill and TikTok being banned is a real marker for just how far we’ve gone and how much it’s going to take to shake the idea that’s made it into the American political bloodstream — that US-Chinese technological interaction is somewhat akin to doing deals with the enemy, and any sort of commercial or technological engagement needs to be viewed through that lens because of the broader challenges that are facing the US and China.

There’s something that I find so sad about the moment we’re in, because I don’t think it was inevitable that the US and China had to end up where we are today. I’m going to put it 90-10 on Xi and Beijing’s shoulders for pushing us to this moment. But when I look at the likes of Zhang Yiming — we would be in a much nicer world if the two countries and the two systems were in a place where they could build trust in each other. Shou could be thinking about how to make creators more money and not have to spend all his time on completely justified concerns about data privacy and algorithmic bias. But that’s not the world and timeline that we’re in.

There’s something about the discourse in the US around the US-China relationship that isn’t grappling with the tragedy of all of this. The most tragic thing is not necessarily just the US-China tech relationship, but the trajectory of Chinese governance over the past ten to fifteen years. It’s deeply sad that this is the place that we’re all in.

Kevin Xu: The marker of this being the end of an era with the TikTok hearing today and the RESTRICT Act possibly becoming law is not that hyperbolic. I work with entrepreneurs from different places around the world, and I have held hope that while products like TikTok pose more obvious national security threats and could be dealt with in one bucket, there are many more tech industries that are just trying to make more money and justify their valuation with their VC investors. These are just normal behaviors in business that used to be much more free-flowing, but now they’re all being shoved under the larger movement of an increasingly adversarial relationship between the two countries. This is a new level of separation that I have not seen in the past three decades.

There’s not a whole lot of wishful thinking. The reality is that people need to change their plans. That has nothing to do with whether TikTok is a national security threat or not — which there’s evidence to suggest that it is. There could be more validation on that claim, and we could have dealt with it singularly. There are opportunities where TikTok could have led the pack or really stayed in front of this problem, whether it’s open-sourcing their recommendation algorithm or even the access level between their Chinese and American engineering forces to show more actual transparency — instead of building a “transparency center” and parading a few journalists around. Those would be ways to technically verify these claims — but unfortunately, that didn’t happen with TikTok. So here we are.