TikTok, Trump as C-Rate Banker, Huawei's True Bottleneck

TikTok Update

I wrote an updated version of my earlier TikTok piece for Lawfare. Some new beats:

Zhang’s posts on the microblogging platform Weibo from the early 2010s positively contrasted America’s freedom of speech with restrictions in China. It’s a bitter irony of the current climate following with the past two decades of US-China tech entanglement that the US today can't afford to trust a Chinese CEO who probably holds values closer to those of American society than the Chinese government’s.

Even if ByteDance makes gestures toward this with initiatives like transparency centers purportedly allowing independent observers to peek into the TikTok algorithm, the fundamental issue is a problem of trust and accountability. While Zhang has been trying to offshore more of the functions of ByteDance’s overseas products, this process is so early along that the U.S.-based engineers don’t even report to Mayer, TikTok USA’s CEO.

While I agree that TikTok could not continue to operate in the US while controlled by Bytedance, the method Trump going about executing this policy couldn’t be more counterproductive. Taking this step against Bytedance is a tough call. It means that any hope of enticing Chinese capital to continue investing in America is over, and life will get even harder for American firms trying to maintain a foothold on the mainland. More importantly, the optics of Trump demanding a, probably not even legal, finder’s fee to the Treasury are awful. I’m old enough to remember way back when in 2016 America used to credibly preach the gospel of due process and rule of law around the world.

It didn’t have to go this way. CFIUS could have released a report outlining the concerns they had with Bytedance’s acquisition of Musical.ly, forced a sale, and left it at that.

Instead, we’re forced to watch Trump playact as a C-rate banker who can’t add or subtract but spends all night screaming over house music to make introductions at Buddakan surrounded by bored models he paid to accompany him. He then takes photos of the businessmen cheating on their wives. Next, after the deal gets going, he threatens to send photos to TMZ unless he receives a 10% cut. To top it off, on his Joe Rogan Show appearance a week later he brags about the photos on air just for kicks.

Even the corrupt Chinese officials I discussed last week know that it pays dividends to be more subtle than this.

What’s the right way to handle concerns about the influence of foreign social media platforms? With repeatable and consistently enforced country-agnostic regulations that require both American and foreign firms to submit to the same verifiable standards for data privacy, algorithmic transparency, and content moderation.

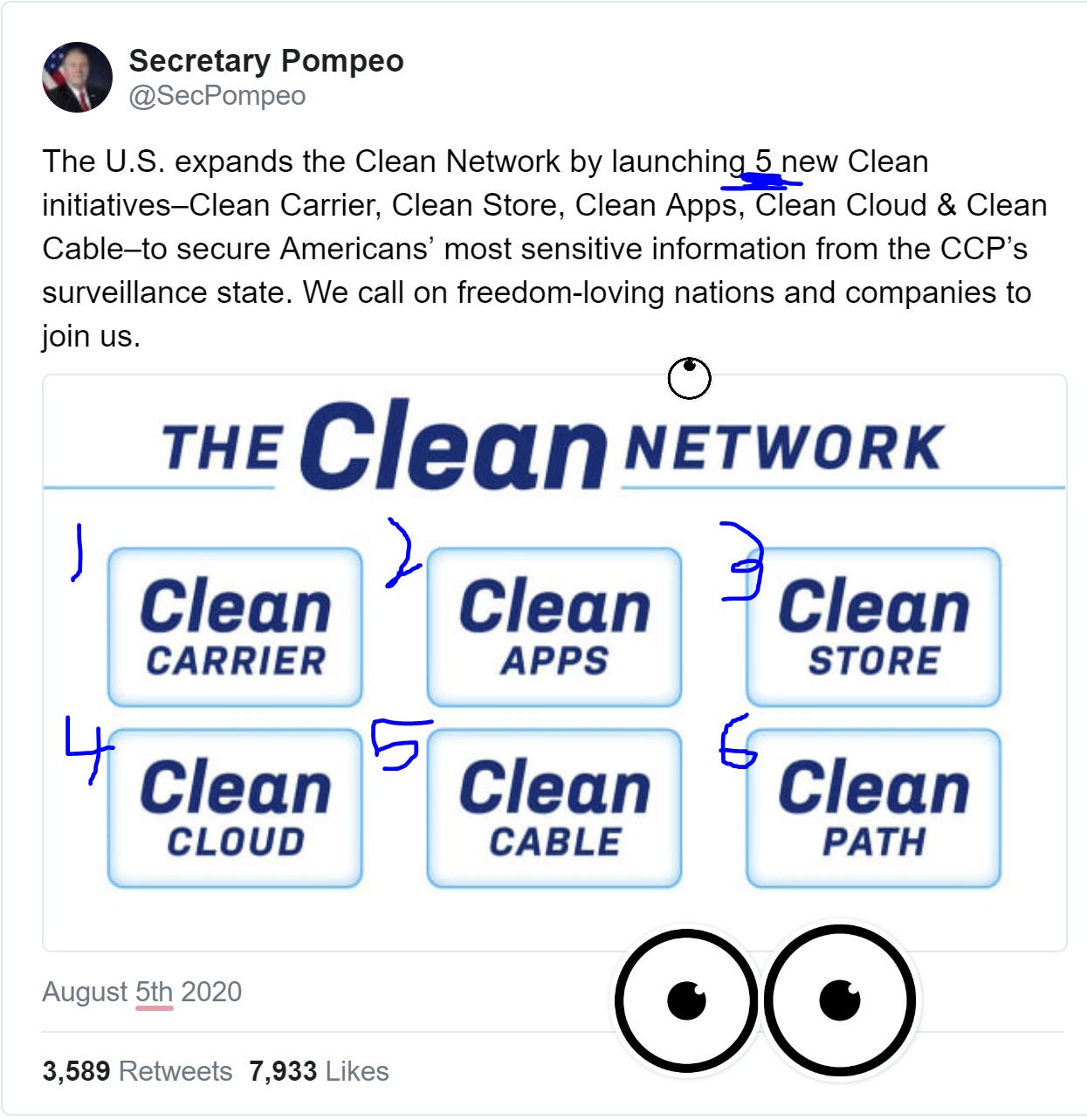

But what we have now with Trump’s handling of TikTok combined with this ‘clean network’ nonsense from Pompeo is more damning to our global standing and ability to advocate for an open internet than anything Global Times could have dreamed up. Pompeo literally said “five cleans” as if he worked on the Chinese State Council when for god’s sake there are six cleans in the slide! It’s really not too much to ask that in this tech cold war Trump is marching America into he not at the same time gratuitously ape the worst aspects of the CCP.

Huawei’s True Bottleneck

In a recent article titled “Where is Huawei’s true bottleneck?”, Wang Tao, a science and technology commentator, reckons with the company’s place in the world. “A company that is the industry leader comes to represent the whole industry,” he writes, while “a company that is a national champion cannot avoid a role in global politics.” He argues that the fast-follower model Huawei is following will ultimately reach a limit.

Though headlines have fixed Huawei as the most prominent firm caught in the crosshairs of the US-China tech war, Wang’s analysis centers on Ren Zhengfei’s unique position as leader and the way the firm treats its broader competitive ecosystem. He argues that though companies typically stress the most about attracting quality talent, in fact, an even more urgent problem is developing the talent and careers of employees already at the company. As a company becomes more successful, its ranks are naturally staffed with more ambitious and capable egos than the firm’s management ranks can satisfy. Wang points to GE as the company that has best addressed this problem by welcoming top managers to pursue outside opportunities. Through this approach, GE has avoided getting derailed by internal clashes while building up a great network of leading executives at other big firms.

But a company’s top talent is not limited to managers—it also includes skilled specialists who have their own ideas for new products. Given a limited budget, companies cannot invest in all of these. Wang describes an approach, best represented by Cisco, that encourages specialists to go out and start their own enterprises, in some cases even providing them with initial investments. If the new enterprise is successful, Cisco regularly hires back its former specialists through acquisition deals. Ren Zhengfei, however, has not committed to this sort of model, do the detriment of the broader Huawei ecosystem it needs to develop to truly gain independence from the US.

The following excerpt was translated by Daniel Huang. The original article was published on June 12th and had 40k readers.

Huawei’s Bottlenecks

In its development and management, Huawei has sought ‘extreme learning’ from Western companies, adopting the approach of “first rigorously copy, optimize later, [then build a moat].” This has largely been the case in its R&D, logistics and distribution, operational flow, finance. But Huawei also has some very unique features in its management approach. For example, a company’s stock typically signifies:

Rights to control and be involved in strategic decision-making

The right to receive dividends

The right to sell stocks and cash in on company’s value

Capitalizing operations and financing functions

But at Huawei, stocks have shed many of these functions and to a large extent become solely an instrument to distribute award money. On the internet, it is often claimed that Ren Zhengfei only owns about 1 percent of the stock. At a typical company, this rate of stock ownership would be a purely symbolic act without any real controlling interest. But at Huawei, Ren Zhengfei is the firm’s undisputed boss, holding the elevated status of a religious leader, and hardly needs to rely on stock ownership to wield power and control within the company.

See this Zhihu post analyzing how Ren modeled his leadership style on Mao Zedong. Folks without Chinese can google translate to get the gist. For some excerpts:

Duan Yongji, the co-founder of Stone Group, visited Huawei and asked how much Ren Zhengfei has. Ren Zhengfei replied: "I own very few shares, less than 1%. The top management adds up to 3%."

Duan Yongji said: "Then have you considered that one day others may unite to overthrow you and drive you away?"

Ren Zhengfei replied: "If they can unite and drive me away, I think this is precisely reflects the company's maturity. If one day they don't need me and unite to overthrow me, I think it is a good thing.”

And later the piece: “Huawei’s culture is, in a sense, the Communist Party’s culture. Being ‘customer-centric’ is the same as Serving the People; fighting for Communist ideals above all personal enjoyment is just like our struggle culture...”

The status of Huawei’s chairman and CEO could not be more different from their counterparts at other firms. The model of a rotating CEO only has a few predecessors in history: in Rome, for example, only the military’s most powerful commanders operated using such a rotating model [to disastrous effect at Cannae]. In reality, Huawei’s rotating CEOs are less akin to true CEOs than rotating secretaries who answer to Ren Zhengfei. This is the only way to properly understand a company like Huawei. Such a model can only exist with Ren Zhengfei at the company’s helm. With many capable candidates to serve as Huawei’s CEO, how do they get their turn?

If Huawei can surpass its own markers of success, it can help proliferate a boom in outstanding Chinese high-tech companies and innovation, creating a new ecology. In fact, Huawei has already fostered a surge in innovative startups and world-class managers. This was not necessarily Huawei’s intention; instead of being a positive effect of the company’s operational behavior, it was the individual actions of former Huawei employees. In this matter, Alibaba and other internet companies have performed much better.

Can Huawei’s ecological development transition from within the company to beyond? We can only wait and see.

What is the root cause of Huawei’s pain?

Why is Huawei facing so much suppression from the US today? Many believe this is caused by the US-China tech war. Of course, this is among the core reasons.

But if observers only focus on Huawei as an instrument in the US-China contest, they miss seeing the whole picture. From the beginning when Huawei entered the American market, it locked into fierce competition with Cisco, which constantly morphed its industrial ecology to arrive at new means of suppressing Huawei.

How big was Cisco’s industrial ecology? It wasn’t merely in Silicon Valley but had common interests with an enormous network of integrated businesses and agents all over the world. To make things even more clear, Cisco also sold its products to businesses and agents representing the FBI and CIA. How would Cisco feel once it found out Huawei’s prices were significantly lower? Of course, it urged its FBI and CIA clients to help suppress Huawei.

When Huawei was competing with Moto and Lucent, none of these companies had an extensive industrial ecology. Competing with Huawei was natural business practice, and Huawei easily prevailed over such competitors. But CISCO is completely different, which is why to this day Huawei has been unable to shake up CISCO’s market and continues to suffer invisible limits on its rising influence. It is only with the backdrop of intensifying US-China tensions that the long-standing competition between Huawei and CISCO has magnified.

The reader must understand, none of this is guesswork. I’ve had extensive contact with Huawei’s personnel and clients in the US market. Many of them were formerly my own clients.

Actually, America has not necessarily only treated China as an opponent. It has considered ways of co-existing and collaborating, including the proposed G2 and establishment of “Chinamerica.” It was not that China was unwilling to collaborate and co-exist, but rather that America’s model of profit-making is fundamentally at odds with China’s vision of an ideal future world. We wish to achieve prosperity through hard work, while America primarily operates through its supremacy and exploitation of other countries. China cannot follow along with America’s exploitation of others. But the situation is also different when it comes to enterprise. Competition is not necessarily inevitable. As long as there is the desire to cooperate on development, there is always a way.

If you don’t even know who your enemies are, how can you possibly defeat them? The main opponent Huawei faces is not the American government. The broader Chinese public might think so, but Huawei must not have such a simple view.

When Huawei announced the development of its Hongmeng operating system last year, I said that the system’s success would not depend on its technology, but rather whether the company can successfully create an ecology. Many people say Huawei has the ability to create an ecology; many Android apps only need some simple tweaks to be able to function on the Hongmeng OS. But the difficulty is not in whether it is possible to launch apps on this operating system, but in whether people are willing to create apps on the system, and whether their smartphones are willing to adopt this system. If others enter into your ecology and face a situation where they will ultimately compete with your core business and get eaten by you, how many would be willing to do so? Pure software apps may be willing to collaborate with Huawei. But HiSilicon and Huawei phones belong to the same company—why would other phones adopt the Hongmeng OS? And why would they adopt HiSilicon’s microchips? Don’t listen to the online news about smartphone companies that might use HiSilicon’s microchips; these companies really don’t care about their core business if they’re willing to hand it over to a competitor. To be blunt, I can’t imagine how this would happen. As a Chinese in the middle of the US-China tech war, we will choose patriotism. But to expect a person to accept something that clashes with their company’s core business advantage in order to be a patriot is unreliable.

Can the core of Huawei’s success continue indefinitely?

The communications field has a remarkable feature: all future technological developments will be based on the standards drawn by ITU, which everyone currently uses to make their products.

In its development process, Huawei has adopted a clear strategic model: be a fast-follower.

On the matter of individual strategic campaigns, use Mao Zedong’s military philosophy of concentrating your superior forces (known as the “pressure doctrine”). In the areas of special technology and special directions, concentrate investment to far surpass what resources your competitors have. Employees must work day and night; at the point when the competition is about to grab market share, do not spare any expense to seize the mountaintop.

The communications market has a high degree of stickiness. Once you occupy the market, you can await the subsequent expansion and obtain great profits. Because of this, Huawei does not need to make in-depth evaluations on the direction of the market.

Once the mainstream technology fluctuates and becomes less certain than what people had thought, Huawei will always have a period of strategic misjudgment. However, because Huawei’s ability to concentrate its best talent is unmatched, even when there is a period of misjudgment, it will still be able to prevail in the end.

The classic example is with cellphones. In the beginning, Huawei resolutely did not produce cellphones for a long time. Then once it started, it committed fully until its cellphones were the best around. Crucially, after entering the era of smartphones, they became not simply fashionable products like the in 2G era but semi-standardized products that were differentiated not in appearance but performance. With its long history of successful experiences, Huawei has come to rely less on precisely predicting the direction of development.

At the same time, it could be said that Huawei has emulated foreign technological and management practices to the max. It basically searched in each country’s advanced research institutions for methods of technological advancement.

Just like heroes and sinners that are only a half-step apart, truth is also only one step away from fallacy. In the past when Chinese companies were learning from abroad to improve its technology and management, they stood to gain in every case. Huawei was the only one; successfully following the model of others was a strength common to many Chinese companies. But because China was so successful at this, the companies we could emulate have basically been used up, and today China must urgently transition into a strategy of original innovation and technology leadership. If other people's innovations cannot lead to reaping the benefits of subsequent success because they are always wiped out by latecomers who use strong military tactics, who else in China will be willing to innovate?

This is not any individual company’s problem, but a fundamental problem with China’s science and technological development. Otherwise, as soon as we’ve exhausted following the lead of foreign companies, we ourselves will quickly have no way to go forward.

China Twitter Tweets of the Week