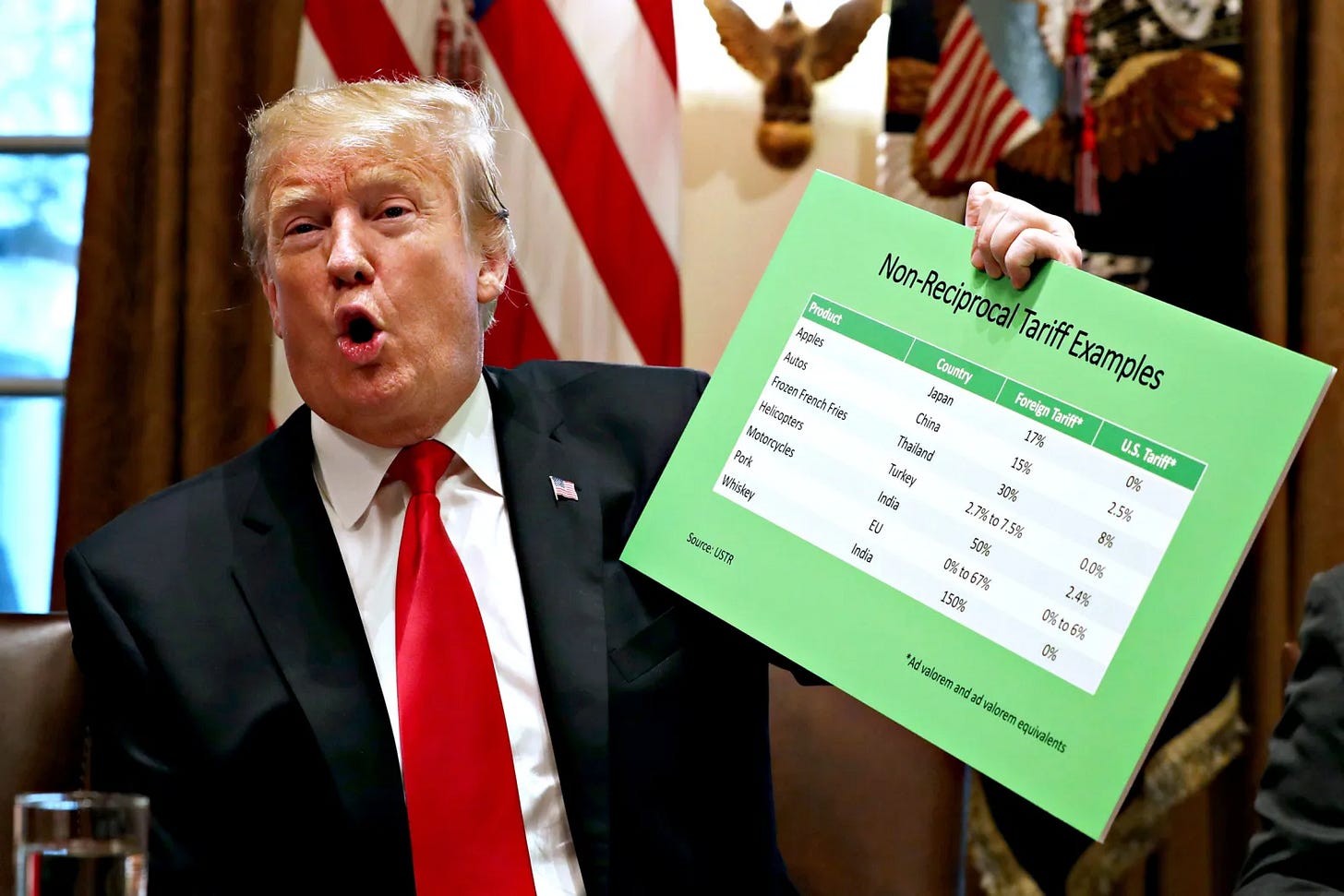

As Trump throws 10% tariffs on China and 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico, it’s worth reflecting back on the long scope of America and trade.

Back in 2019, back when this humble substack was still called ChinaEconTalk, we interviewed the dean of US trade history Doug Irwin about his magisterial Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy.

In this interview, we discuss:

A historical tour through 250 years of American trade policy;

Parallels throughout US trade history to recent policy;

The evolution of GATT and the WTO;

Whether tariffs now are likely to have the intended effect;

The three R’s of tariffs: revenue, restriction, and reciprocity.

Transcript below, or a listen on iTunes or Spotify.

Jordan Schneider: James Madison holds a special place in my heart because I’ve acted him on stage. He wrote in “Federalist No. 10” that, “it is in vain to say that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust clashing economic interests and render them all subservient to the public good.” Boy, was he right.

Over American history, trade policy stands out as a field of fierce political combat. What are the principles that drive American trade policy? What lessons from history can we draw on to understand today’s trade fights?

To discuss, we have on Dartmouth professor Doug Irwin. Doug is the author of a 700-page history of American trade policy from American Independence to the present day. Doug, welcome to ChinaEconTalk.

Doug Irwin: Thanks, it’s a pleasure to be here.

Jordan Schneider: You mention in your acknowledgments that you thank your wife for putting up with your interest in such an arcane field of economics. Maybe when you guys were dating, you probably gave her a pitch as to why you actually care about trade policy and why it’s interesting. How has that pitch changed over the course of your career?

Doug Irwin: There’s the personal level and then there’s the professional level. The secret is that I married an economist. It didn’t take all that much for her to be persuaded that trade is important.

Jordan Schneider: That’s cheating, man.

Doug Irwin: It is cheating a bit. We have a lot to talk about. She is a macroeconomist, however. She doesn’t really think micro is all that important or interesting. However, even she would grudgingly admit today that trade policy is important.

What’s amazing about the present era is that with President Trump and all the headlines about trade, one really doesn’t have to motivate the idea that trade policy is important and interesting for the world economy. If you go back 10 years or so, that wasn’t the case.

There was a period in my career when trade policy was a sleepy backwater of economics. Tariffs were low and stable. Countries weren’t using trade policy to achieve any particular objective. The world seemed to be moving in a liberalizing direction. There wasn’t much to say.

Now we have all these trade policy experiments with tariffs going up on China, on steel and other things. Economists are writing tons of papers on these topics. It’s obviously making the front page news, above the fold even, in terms of some of the macroeconomic impacts of these tariffs. It’s disheartening in a way, but for a trade economist, these are really interesting times.

Jordan Schneider: From a drama perspective, how would you compare this to fights over monetary policy throughout history?

Doug Irwin: That would be another great book to write, the politics of monetary policy from the very beginning. We’re at a sort of local peak in terms of interest and dissension over trade policy in terms of what President Trump has been doing.

With the book I cover more than 200 years of US history. There was this period in the late 1820s when the US was literally threatening to break apart over the issue of tariff policy. The South objected to the high tariffs that were being imposed because the North sort of controlled the political process.

I don’t think we’re at the stage of breaking up the United States over trade policy. But it’s pretty intense at the moment with the debates going on about trade policy.

Jordan Schneider: I imagine that was one of your favorite sections to write. As you made it through the entire sweep, I’m curious if there were some low points as well as high points?

Doug Irwin: I didn’t set out to write this book or anything. I didn’t have this conception 10-15 years ago that I’d write a book to tell the whole story of trade policy from the very beginning to the very end. I backed into it.

I started writing papers on trade policy in the Great Depression. I found it very interesting. It was a lot of fun and not too many people were working in that area at the time. I said, let me go back a little bit further in time. How did we get to the Great Depression period?

Slowly I moved backward and forward from the 1930s. After a few years, I realized that I had covered some of the big events in terms of the history of trade policy. Maybe I should put it all together in a book and cover some of the gaps and fill in some of the holes. It came about in a haphazard way when I ultimately decided to write the book.

Of course, some periods are more interesting than others. The late 19th century from after the Civil War up to World War I was a pretty stable period. There are a lot of forgettable presidents. There was a lot of gnashing about trade policy, but not a lot of action, a lot of status quo bias if you will.

Jordan Schneider: But there’s a “Cross of Gold.”

Doug Irwin: That’s true. That’s more monetary policy than trade policy per se, but they’re related to some extent. That was one of the slower periods, but it’s also a very interesting period. It’s not so much because of the trade politics of the period, but because of the debates over what the impact of trade policy was in terms of fostering US economic growth and industrialization.

That’s really the big debate in the late 19th century, not big fights over whether tariffs should go up or down a little bit.

Tariffs as Revenue: pre-Civil War Trade Policy

Jordan Schneider: Let’s start quickly with the dynamics of pre-Civil War trade policy. Why do you argue that it’s dominated by concerns around revenue raising?

Doug Irwin: Actually, you asked me what were the more interesting and less interesting parts of the book. The earlier parts are really interesting.

One of the motivations for having the Constitutional Convention was to solve a policy problem: trade policy. When we got our independence, we had the Articles of Confederation which didn’t endow the National Congress with the power to tax anything. Yet the national government needed to spend money on defense, paying foreign debts, and what have you.

The Constitutional Convention was to solve that problem by giving the government the power to tax. By unanimous consensus, the idea was we’re not going to have income taxes. We’re not going to have sales taxes. You might’ve heard of the Whiskey Rebellion. Sales taxes didn’t work out so well.

Import tariffs were this anonymous way of taxing goods as they came into the US economy. I wouldn’t say we were dependent on trade, but we relied on trade quite a bit. We imported a lot of goods that we couldn’t produce here. They came into 6-12 ports on the East Coast.

That’s easily taxed. The taxes were embedded in the price of the product that the consumer pays. Everyone agreed that import tariffs were going to be the way to raise revenue for the federal government.

With the Constitution, we were having the first debates over what we wanted to achieve with our trade policy. The US was starting out on its own as an independent country and thinking about what its trade policy ought to be and what principles ought to be underlying it.

Jordan Schneider: How is this history relevant today?

Doug Irwin: You would think that it wouldn’t be so much.

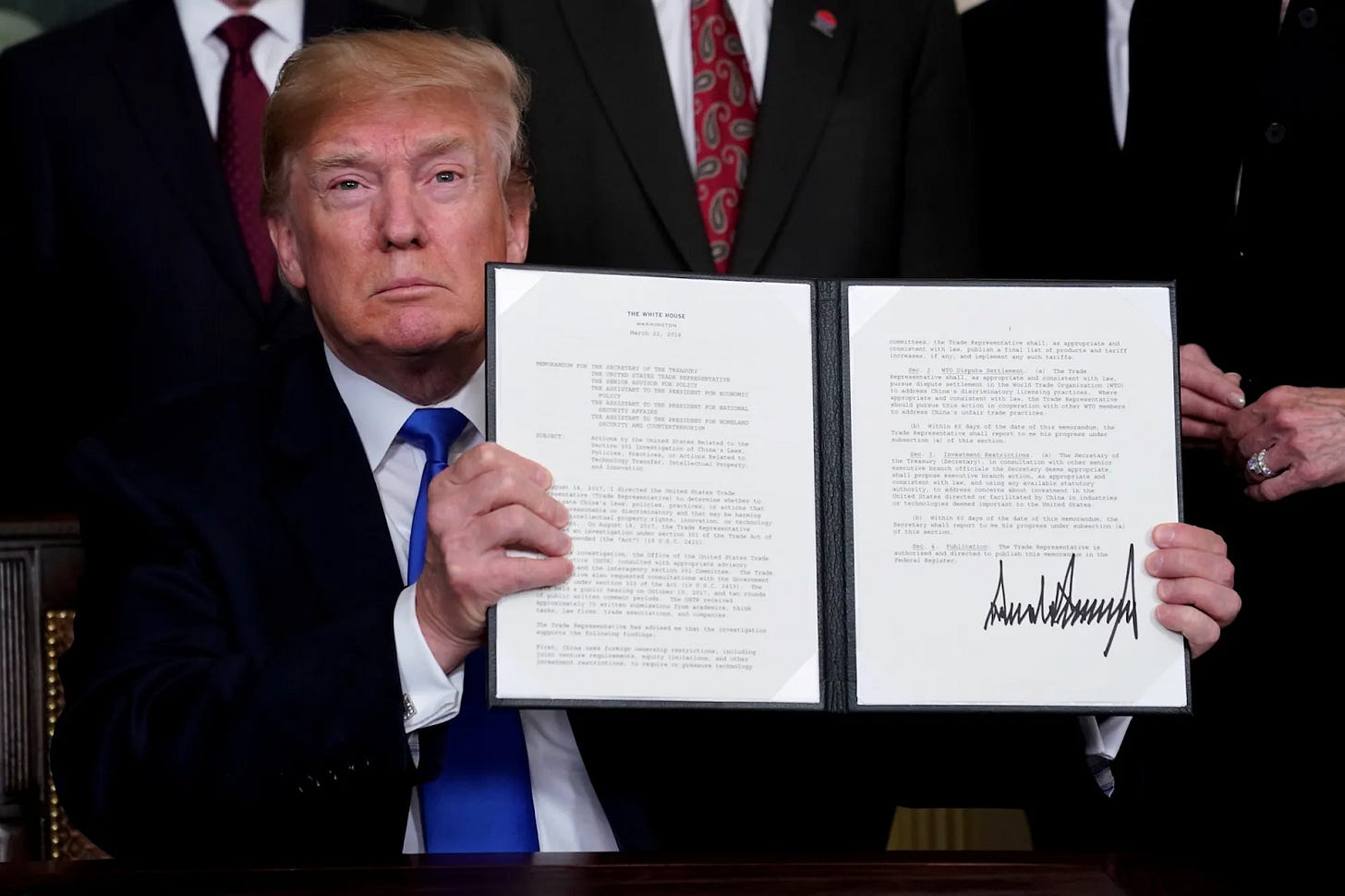

It is in two senses that are directly related to the debates that the Trump administration has unleashed. Under the Constitution, Article I, Section VIII, Congress is empowered with the authority to levy taxes on imports. What happened in the late 20th century is that Congress delegated a lot of those powers to the president.

Now the president, President Trump, has seized upon this to impose and justify the imposition of tariffs that he’s done, without Congress’s consent. There is a discussion today at least about the role of Congress and trade policy and the Constitution. That’s one way in which it’s played into debates today.

The other is that after the introduction of the income tax in 1913, the share of federal government revenue coming from the tariff just plummeted to trivial amounts, less than 1% of US government revenue today.

One of the president’s selling points is that his tariffs are raising a lot of revenue. He tweets a lot about how our coffers are being filled with millions, if not billions, of dollars. Other countries are paying for the privilege of sending their goods to the US.

He’s raised revenue as a reason for imposing tariffs today. That idea of revenue has come back into play as well. In looking at more than 200 years of US trade policy history, there’s a lot of recycling of arguments, a lot of reinventing the wheel. There are a lot of debates that take place today that took place, 50, 100, 200 years ago.

There are some underlying themes and issues that come up with trade policy that are always present with us.

Tariffs as Restriction: New Protectionist Politics

Jordan Schneider: Trump certainly takes cues from mercantilist British empire-inspired economics. Let’s now turn to the restriction phase, which you argue was the first fundamental shift in US policy.

Doug Irwin: One of the themes of the book is that when we ask what the federal government is trying to achieve in levying tariffs on imports, I have what I call the three Rs: Revenue, Restriction, and Reciprocity.

Revenue is straightforward: taxing foreign imports raises money for the federal government.

Restriction aims to keep imports out to create jobs in import-competing industries and strengthen the American economy. That argument has been very potent and been around for a long time. The Trump administration points to this, saying we’re helping the steel industry, etc. You hear that in past decades as well.

Reciprocity, which we’ll discuss later, involves using trade policy to negotiate with other countries to reduce their barriers. You’ll reach these agreements to reduce trade barriers and increase bilateral or multilateral trade.

The transition from revenue to restriction took place in the 1860s.

One of the secondary themes of the book is that when determining what phase we're in or who's calling the shots in trade policy, it comes down to regional politics. Which regions benefit from trade or trade barriers? Which regions have the most political power in Congress and the federal government?

The reason we shifted from revenue to restriction in the 1860s is that prior to the Civil War, the South was politically dominant in the United States, particularly in the Senate. The South was responsible for most US exports at the time. Cotton was a big one in particular, but you also had tobacco, indigo, and other commodities. With their political power, they dictated relatively open US trade policies with low tariffs to keep exports up.

The Civil War caused a realignment of political power in the United States. The North became dominant, not just because the South left Congress during secession. Even after the war, the South was much less politically powerful than it had been. Import-competing manufacturing industries had arisen in the North in the first half of the 19th century. They wanted trade restrictions. They used their political power from 1860 until after World War I to establish high tariffs as the US trade policy regime.

Jordan Schneider: Doug, talk a little bit about logrolling. What was it and what impact did it have on US trade policy?

Doug Irwin: Logrolling is a political science term describing how votes take place in Congress. Political scientists and economists have used it to explain how the high-tariff regime was maintained for so many years in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

It relies on vote trading among members of Congress to keep tariffs high. For example, Florida doesn’t produce steel, but Pennsylvania does. Pennsylvania’s senators and representatives want high tariffs on imported steel. Most states don’t produce steel, however, so how and why would Congress ever vote for high prices or high tariffs on steel?

Members of the Florida delegation care about sugar. They want to keep out sugar imports. Maybe in West Virginia, they want to keep out coal imports. Various state delegations will get together and say, “I’ll vote for your steel tariff if you vote for my sugar tariff.”

This vote trading, known as logrolling, gives rise to an interlocking coalition that makes it very difficult to push for lower tariffs. While most states might like lower tariffs on steel, they don’t want lower tariffs on their own goods, and they've collaborated to keep these tariffs high.

This is one reason why in the late 19th century even the Democrats, who came largely from the South, had almost zero success in reducing tariffs. They had to face these logrolling coalitions in Congress that are very difficult to defeat.

Jordan Schneider: My favorite part about trade history is we’re not just talking about the big steel, indigo, tobacco types of goods. We’re also going way down into the weeds. We’ve got bird cages, fur hats, crayons. It just keeps going and going because the interests are extraordinarily local and you can have individual line items for all these different types of goods.

Doug Irwin: Throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th century, whenever Congress considered a tariff bill, it consisted of up to 3000 individual tariff lines on individual products by the 1930s. Behind each of those products, there are some producers located in some states who are going to let their representatives and senators know that they really value those high tariffs.

You get members of Congress defending and debating the clothespin tariff, the tomato tariff, the felt skirt tariff. By the time of the Smoot-Hawley tariff in 1930, it was taking weeks, if not months, to get through the Senate. They would literally have roll call votes on each of these individual tariff lines, sometimes more than once. It does get into the nitty-gritty.

Jordan Schneider: I love how you have some quotes from senators and representatives talking about how basically this is the worst part of their job. They were happy to end up seeing it go just so they could spend time doing other things.

Doug Irwin: That’s one reason why Congress ultimately decided to delegate tariff authority to the president. They didn’t want to deal with the tomato tariff and the clothespin tariff. It was taking up an enormous amount of legislative time.

Of course, Washington would be besieged by special interest groups whenever Congress decided to take up the tariff. They said, “We have much more interesting and important issues to deal with than fighting these micro battles. We’re just going to give this to the president.”

How Bad Tariffs Can Wreck the Economy

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned the Smoot-Hawley tariffs, perhaps the most famous tariffs in world history. What were they and why did folks think they were a good idea at the time?

Doug Irwin: The Smoot-Hawley Tariff was passed by Congress in June of 1930 and then signed by President Hoover. It’s been infamous. First of all, the name is catchy: Smoot & Hawley. It’s not a regular term. It has a nice cadence to it.

It was a very ill-timed tariff in the sense that it occurred right as the world economy was slipping into the Great Depression. When it was originally proposed in the late 1920s, the US economy was doing very well. We were close to full employment. The stock market was booming. Industrial production was growing. The economy seemed to be doing well.

It was introduced in Congress in 1928-1929. The idea was that the farm sector was lagging and wasn’t doing so well. There were dislocations as a result of World War I and overproduction and overinvestment in land. We had to help farmers cope with imports. We had to raise their prices in some way.

In fact, Congress had twice passed price supports in the late 1920s but President Calvin Coolidge vetoed both of those pieces of legislation. Congress was groping for some way to help out farmers in rural America. Price supports seemed to be the obvious way of doing it, but the president didn’t want that.

They said maybe the tariff is the second-best way of dealing with the issue. Even though I explain in the book why it really wouldn’t have helped out farmers that much. Most big farmers were big exporters, not facing foreign competition or imports.

Here’s where logrolling comes in. The tariff was motivated originally to help out the farm sector and agriculture. However, once you start talking about the tariff in Congress, then the fishbowl industry and the tomato producers and steel producers start coming out of the woodwork. They start saying, “If you’re going to raise those tariffs, you might as well raise ours too. We could always benefit from capturing a little bit more market share by keeping out foreign competition.”

By the time it passed, it was an almost across-the-board tariff increase. The US had the stock market crash in late 1929. The world economy was becoming increasingly fragile. Congress didn’t really think about foreign ramifications in terms of retaliation.

What ultimately happened is that other countries did retaliate against the US. That hurt our exports. World trade began to contract. That exacerbated the Great Depression, which we had already begun to slide into. It became this trade policy disaster that the US spent about 20-30 years trying to pull our way out of.

It wasn’t just that other countries raised their tariffs against our products. They also formed these trade blocs that discriminated against the US. In particular, there was the British imperial preference scheme which included Britain, Canada, and others, big markets for US produce. Now the US faced not just higher tariffs, but discriminatory tariffs in those markets.

Smoot-Hawley was really this unnecessary, unwise piece of legislation and very ill-timed. It created big problems for a long time for US trade policy.

Jordan Schneider: Interestingly, you have a quote from Peter Navarro in your new Foreign Affairs piece talking about US-China trade relations. Navarro said, “I don’t believe there’s any country in the world that will retaliate for the simple reason that we are the biggest and most lucrative market in the world,”

Little did he know, had he read your book and understood the reactions to Smoot-Hawley, perhaps he would have thought a little harder about the international reaction.

Doug Irwin: There’s absolutely a parallel there. Some Democrats in Congress said we ought to really think about this carefully and not just consider domestic interests but also our export interests. They warned that other countries might retaliate. Basically, the reaction of most members of Congress, Republicans at the time, was, “Nah, we don’t have to worry about that.”

They thought, “This is a domestic piece of legislation. It doesn’t really concern other countries. They’re not going to retaliate.” Of course, they did. That seems to be one theme. Some policymakers or trade policy thinkers will understate or downplay the idea that other countries will retaliate against us.

Sometimes these groups are called economic nationalists. That's what Peter Navarro might call himself. What they don't realize is that there are economic nationalists in other countries too. If we aggrieve other countries and hurt their exports, they don't just say, “oh, I guess there's nothing we can do about that.” They get upset too when they're nationalists. They say, “we have to strike back against the Americans who cut out our markets.”

The reason why the Europeans were particularly concerned about this in the late 1920s and early 1930s is because they were trying to repay their war debts to the United States as a result of World War I. They needed to run trade surpluses with the US. Their ability to do so was hurt by the tariffs that we imposed. There was this financial dimension to what was going on at that time.

Tariffs as Reciprocity: Seeding Free Trade

Jordan Schneider: FDR comes in and the whole trajectory starts to shift. Why does this happen?

Doug Irwin: Here’s another one of these trade policy pivot points. The first one we talked about was the shift from revenue to restriction with the Civil War and the realignment in American politics, shifting political power to the North.

In the 1932 election, we had another political realignment towards the Democrats. It shifted a little bit more towards the South, although FDR’s coalition also included big parts of the urban areas in the North. The political party of the Democrats at the time was much more in favor of freer trade.

The Democrats in the South were still representing export-oriented industries. Urban areas wanted cheap imports for food and other things. The political system shifted back towards freer trade, but it wasn’t a shift towards just abolishing Smoot-Hawley.

When the Democrats had taken over in the past, a few times in the late 19th century, they tried to pass bills just reducing tariffs. The Republicans would try to push tariffs up. The Democrats would try to push them down.

What FDR realized at the time was, first of all, we were in a depression. A unilateral tariff reduction was not going to work well politically and it wouldn’t help us out that much economically. What happened as a result of Smoot-Hawley was that other countries raised their tariffs against us. They retaliated against us.

We have to get rid of that discrimination. We have to get rid of those foreign tariffs. The way we’re going to do so is by bargaining. We will reduce our tariffs on your goods if you reduce your tariffs on our goods, get rid of the discrimination. That’s why FDR didn’t say we’re going to just slash or unilaterally cut tariffs, we’re going to start bargaining.

That’s the introduction of this third phase of US trade policy, the third R: reciprocity. We’re going to negotiate with other countries. The Roosevelt administration pushed for this piece of legislation in 1934 called the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act. It empowered the president to undertake those trade negotiating activities. That’s where we are, that's the regime we’re in today.

Congress no longer sets the tariff rates themselves. They don't pass these long, complicated tariff bills with individual tariff lines. They rely on the president to handle trade policy, within some circumscribed limits of course. The president is really the main trade policy actor today. That's where we've been since the 1930s.

Jordan Schneider: Did you dig at all into the intellectual history of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements, the whole idea of this? It does seem very much like a change in paradigm, as opposed to trying to plug away at these existing edifices.

Doug Irwin: Certainly, there was discussion in the progressive era about how Congress is slow and doesn’t really think about the national interest all the time but rather special interests. We need to empower a very strong, quick-acting executive. We need these expert administrative agencies to handle our policy, whether it’s the creation of the Food and Drug Administration, or other agencies like that.

There was this idea that we wanted to create this impartial, non-political tariff board that would adjudicate tariff issues. That didn’t work out so well. The idea had been floating around for some time that Congress is really not the best forum in which to debate these tariff rates. The phrase at the time was, “take the tariff out of politics.”

Really, there’s no way you can do that but the idea was to separate it from Congress. The idea of delegating authority to a branch of the president in particular had been floating around for some period of time.

Jordan Schneider: The RTAA definitely had its detractors at the time. Some said that it was a, “Fascist dictatorship with respect to tariffs.” Another said that, “There are no shackles upon this use of extraordinary tyrannical, dictatorial power over the life and death of the American economy.”

Also there was an American Tariff League that was pushing back against this. What does the pushback say about the politics at the time?

Doug Irwin: There’s another parallel to what we see going on today. We don't want to point fingers to anyone in particular. At the time the Republicans who were opposing this groped for any argument to object to something.

If a Republican president had said, “I need these tariff powers,” — in fact Hoover got some tariff powers in the Smoot-Hawley Act — Republicans would have been fine with that. The problem was not so much that they were delegating powers to the president. It’s that they knew that President Roosevelt would use that power to reduce tariffs. They cared about the outcome. They were objecting to the outcome that tariffs would go down as a result of this delegation.

This is something we see today when some of the political parties say, “We oppose this measure because it’s unconstitutional or it’s a bad policy framework.” They’re really objecting to the outcomes that they see in giving a certain administration certain powers.

The reason they lost is that they didn’t have the votes in Congress. They were a minority party. They could scream all they wanted to but they had no real impact on how events played out.

Jordan Schneider: When did the American Tariff League die out? Is Trump going to bring them back?

Doug Irwin: Could be. I still see references to them in the 1950s and maybe even the early 1960s.

By the 1950s and 60s, trade was not a big part of the US economy. Japan and Western Europe were devastated as a result of World War II. We really didn’t face a lot of import competition. The need for an American Tariff League was pretty small at that time. There were no major industries that were complaining about imports. We’ll see whether they come back or not.

A big difference between that period and the 1930s — when there was a politically robust American Tariff League — and today is that back then businesses were not really globalized. They were national businesses. There were foreign producers and domestic producers. The domestic producers wanted to keep the foreign producers out. Today, American business is really globalized. Most large companies are multinational. They're operating in many countries at the same time. They're sourcing components if they're in manufacturing from many different places.

We won’t see a revival of the American Tariff League because most businesses today are globally integrated. They rely on imported components. They don’t want the old-fashioned protectionism that we saw in the 1930s and before.

Jordan Schneider: You’re saying if I don’t do it, no one will?

Doug Irwin: There’s an opening for you. Give it a shot.

Jordan Schneider: It’s that or a dissertation on what they were up to in the 1950s. We’ll see which road I go down.

Who was Secretary Hull and how big a role did he play in changing trade policy at the time?

Doug Irwin: Cordell Hull was Secretary of State from 1933 to 1944 and he’s one of the people that most students of American history don’t know about or appreciate his role in terms of US trade policy.

Jordan Schneider: He’s a great character though. He comes from the middle of nowhere in Tennessee. He’s a hillbilly who ends up becoming secretary of state during World War II. It’s a rags-to-riches story if you ever wanted one.

Doug Irwin: He really played an outsized role in redirecting US trade policy in the 1930s. At the time he was made fun of. It was thought that trade policy was not very important during the Great Depression and that this goal of achieving all these reciprocal trade agreements wasn’t doable. The rest of the world doesn’t want them. He’s wasting his time.

He was very persistent. He was very focused on this one goal of using the State Department to try to get more economic peace and harmony through peaceful trade relations. He retired or resigned as Secretary of State in 1944. He was America’s longest-serving Secretary of State. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1945, both for his work on helping to create the United Nations as well as his work on trade policy.

He’s a really big figure that’s a little bit forgotten these days. He really did change the course of US trade policy. The impact of his ideas really came to the fore in the 1940s and 50s, after he left office, with the formation of the GATT (the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade). We now know of that as the World Trade Organization. He really pushed for multilateral trade policies. That came about after he had stepped down from office, but he's a big figure in the history of US trade policy.

Jordan Schneider: There’s a tragic aspect of his story as well. His whole theory was that trade between countries helps bring about peace. One of the decisions that he partially signed off on was the blockade of Japan in 1940, restricting them from being able to import oil.

We don’t need to adjudicate why Pearl Harbor happened, but this was certainly one of the factors in Japan’s calculation that they needed to act. It was because of the power that US international trade had on their economy.

Doug Irwin: His deputy at the time, Dean Acheson, played a role in that as well.

Hull was generally considered to be a pretty weak secretary of state. That’s largely because FDR wanted to run foreign policy under the White House. I still think he’s a bit underrated, particularly in the trade field where he was of critical importance.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s get through World War II. Why does GATT matter then?

Doug Irwin: As we were just talking about, the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act passed in 1934. It really didn’t achieve much in the 1930s. We already had fascist Germany and Japan that didn't want to sign trade agreements. Britain had gone in for imperial preferences with Canada and its former colonies. It was a tough row to hoe for Hull during the 1930s. He really didn't achieve much.

He had this idea that we should bring countries together and reduce trade barriers. It really didn’t come to fruition until after World War II. That’s when the US really was the dominant power in the world politically, militarily, and economically. Britain was much weaker. The US couldn’t really dictate terms but it could set the agenda for where the world economy could go, at least the arrangements relevant to the world economy after World War II.

The State Department said we want to have a big convention after the war to handle international monetary arrangements. That’s what the Bretton Woods Agreement was in 1944. It set up the IMF and the World Bank. We also wanted a big agreement on trade. That was first set up in 1947 at a conference in Geneva. It set out an agreement called the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which set the framework for post-war trade relations.

The State Department actually wanted to do something even bigger and create something called the ITO, the International Trade Organization. There was a conference in Havana in 1948, but it was never approved by Congress and that effort failed. It would have been a great place, I’m sure. Great nightclubs and great music. Of course, the issues were political.

The fact that so many countries had so many divergent trade interests meant they really couldn’t come to an agreement around the table. Whereas the nice thing about the GATT was that it was basically the U.S. and Western Europe and a few other countries that really wanted to focus on trade liberalization.

They came up with this agreement for most favored nation status and other rules for trade as well as exchanging some tariff reductions in the bargaining process. The GATT process really moved forward, whereas the multilateral effort failed at that time.

Jordan Schneider: “Trade or fade” was one of the slogans of the time. I think someone should bring that back nowadays.

Doug Irwin: I think that was Eisenhower or someone in the Eisenhower administration.

What the GATT process did is not just reduce tariffs all at once. There was that first agreement in 1947, but there were a series of trade negotiating rounds about every decade. There was the Kennedy round of the 1960s, which put a further dent in the tariffs. There was the Tokyo round of the 1970s, which ratcheted tariffs down again. There was the Uruguay round of the 1990s, which did a lot of things but also ratcheted tariffs down. It was a slow process over time of reducing trade barriers and trying to constrain trade policy around the world.

Fast Track: Executive Trade Authority

Jordan Schneider: All right. Let’s now get to the next big piece of legislation: the Trade Act of 1974. What were the circumstances around its passing and what did it accomplish?

Doug Irwin: It did a couple of things. It wasn’t as big as the RTAA in 1934, but it renewed the president’s ability to negotiate trade agreements. That’s authority that has to be renewed every now and then. The president could always negotiate, but Congress may not like that. It was necessary for us to have that legislation to go into the Tokyo round.

It also introduced something called fast track, which is another thing we’re still living with today, not just trade negotiating authority. The first trade agreements in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s were just tariff-cutting exercises that didn’t need to go back to Congress to get approval. By the time we’re in the 1970s, tariff levels had come down quite a bit. Trade negotiations were dealing with increasingly non-tariff barriers.

Jordan Schneider: What are non-tariff barriers?

Doug Irwin: Non-tariff barriers would be government regulations or quotas, things that are obstructing trade that are not tariffs, strictly speaking. If you’re going to regulate those or restrict their use, that requires changes in domestic legislation.

The problem was that if the president negotiated some agreement and brought it to Congress, Congress would — just like they did with the Smoot-Hawley tariff — want to put its fingers in the pie and start changing this provision here and modifying that one there. Then you’d have to bring that back to the International Negotiating Forum. They might not like that.

If Congress got to second-guess or change whatever the president had negotiated, it would be a very laborious process that would never really get anywhere. What Congress did with fast track in the Trade Act of 1974, is that if you bring us an agreement that we’ve authorized you to reach, we will pledge to do two things.

One is to get an up or down vote in Congress, in the House and the Senate, and therefore change domestic legislation as a result. We won’t try to change the provisions per se. We’ll just give it an up or down vote, but we do have that right to veto it.

Secondly, we’ll do it within a reasonable amount of time. We just won’t sit on it and let it die a long death. That’s what fast track is. That’s something that's still an issue whenever a president wants to reach a foreign trade agreement.

That’s what we’re dealing with now with the renegotiation of NAFTA, the USMCA. It’s been formally submitted to Congress. They have this timetable that they have to agree to approve it without changing any of the provisions.

Jordan Schneider: I’d like to dive deep on the Reagan era because he probably had the most intense, aggressive, protectionist measures we’ve seen in modern American history.

What drove an administration filled up with dyed-in-the-wool Republicans, whose staff were chock full of Milton Friedman devotees, to drop some really hard trade measures?

Doug Irwin: You have to remember that just about every administration is divided. It wasn’t just Milton Friedman devotees and free market advocates. There are also business people. Business people tend to like tariffs, at least on their business.

There’s a big analogy here with the Trump administration. There’s been this division in the Trump administration as well. At least early on there were Larry Kudlow and Gary Cohn, free market types that wanted free trade. Then you had the business people like Wilbur Ross who wanted to have tariffs to defend American industry against foreign competition. Every administration is divided between different factions. There's usually not just a monolith there.

Yes, Reagan spoke in favor of free trade and he seemed to support that. However, he also negotiated export restrictions on automobiles with Japan and imposed steel voluntary restraint agreements and things of that sort. The reason is that we had the worst recession since the Great Depression in the early 1980s as a result of the Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker tightening monetary policy to reduce the rate of inflation. That recession was accompanied by a very strong US dollar that led to a large trade deficit.

A lot of import-competing industries were being hurt. There was a lot of unemployment at the time, both because of monetary policy and to some extent because of structural changes in manufacturing. It was a way of using trade restraints to limit the damage during this tricky time in US economic history.

It’s a little bit different than the Trump administration today, which is giving the Reagan administration a run for its money in terms of the number of protectionist measures. Today, the US economy so far has been pretty strong. We have very low unemployment rates.

Reagan was dealing with unemployment rates over 10%. Intellectually he was in favor of free trade. Politically he was flexible enough to have temporary measures. Most of these things did go away with time. They were temporary measures to try to offset some of the hurt caused by the tight monetary policies at the time.

Jordan Schneider: I love how you tell this story about a series of events which lead to enormous sugar tariffs. The tariffs were so high that folks ended up bringing sugar in through Canada by means of cake mix, packets of iced tea, and then cooking them down and selling it as raw sugar. That whole rigmarole was actually profitable.

Doug Irwin: We had these import quotas on sugar that drove up the domestic price of sugar to two or three times the world price. You get these imports of fake cake mixes, which are 95 percent sugar. They just took the flour out once it came into the U.S. and sold the sugar at the higher price. There was even a case where we were banning imports of Israeli frozen pizzas because the sugar content was too high and some firms were extracting the sugar to sell it at the higher price.

What this shows you is that there's a limit to trade policy. You can raise tariffs on certain goods, but there's always an incentive to, if not smuggle, at least try to get around those tariffs. There's something called tariff engineering, where you change the type of product that you're sending into the US just to avoid the tariff.

Jordan Schneider: This sort of tariff engineering is going on nowadays as well, right?

Doug Irwin: Absolutely. There was just an article about Columbia, the clothing company. They would adjust the number of buttons or pockets on their shirts so that tariffs would apply to one category of goods and not another.

There was a big debate a couple of years ago about whether Snuggie blankets should be classified as a garment or a blanket. Garments and blankets get different tax treatment in the tariff code. I can’t remember which way it was supposed to go. The company definitely wanted them under the lower tariff category as they were manufactured in China.

One of my favorite examples of tariff engineering I have in the book is that we imposed tariffs on imported motorcycles during the Reagan administration in the mid-1980s. The tariffs applied to motorcycles with piston displacements of 700cc’s and above, heavyweight motorcycles.

What Honda started doing is producing a 699cc version. The difference between a 699cc engine and a 700cc engine is imperceptible. Just by changing that one cubic centimeter, it changed the whole tariff treatment. You avoided a 45 percent tariff and they were assessed at a much, much lower rate.

Reagan vs. Japan

Jordan Schneider: Let’s now turn to Reagan’s relationship with Japan. How did these tensions build up? The complaints you write about at the time seem pretty similar to the charges folks are levying today at China.

Doug Irwin: Yes, they’re very similar to what’s being talked about in terms of China. There are some big differences too.

The similarities are that we had a big and growing trade deficit with Japan, just as we’ve had with China. They were exporting a lot of goods that were hurting US industries, particularly automobiles, steel, and semiconductors.

In the case of Japan in the 1980s, it was a little less obvious what they were. With China, there’s been a lot of apparel and furniture and things of that sort. Certainly some manufacturing industries have been hurt as well as a result of imports from China.

There was also a view that they weren’t fair traders in the sense that their market wasn’t open for our products as our market was for theirs. We had a big trade deficit with Japan just as we have a big trade deficit with China.

The view with Japan was also that their formal trade barriers were low, but somehow we just couldn’t penetrate their market. It was very difficult. The same claim is made about China. Their formal tariffs are low, but the government is behind the scenes with administrative guidance or other mechanisms to avoid buying U.S. products, manufactured goods in particular.

There were also similar concerns about intellectual property. It was thought at the time that Japan didn’t respect US intellectual property and just stole some of our best technology. Obviously, the same is true with regard to China today.

The big difference is that the Reagan administration went after Japan and tried to threaten them and get them to change their policies with trade sanctions. Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 gives the president the authority to do this. That’s how President Trump has also gone after China.

The big difference is that the US and Japan had a very good relationship. We were both democracies, we were both largely market economies. We were both military allies. Japan relied on us quite a bit. Japan really wanted to accommodate US concerns as best they could under the circumstances.

There was a much more amicable agreement to try to do something to reduce those trade tensions. With China, obviously they’re not a democracy. They’re not a military ally. We’re geopolitical and geostrategic rivals to some extent. China’s a rising power. Although we feared Japan as a rising power back in the 90s as well.

The relationship is much more fraught, much more difficult. Obviously China’s a much bigger economy too, the world’s second largest economy. Japan was back in the 1980s as well but it wasn’t considered quite the dominant threat as China is today.

The threats and the bullying don't work as well with China as they did with Japan, which wanted to reach an accommodation with the US. As I pointed out earlier, there are economic nationalists in the United States but there are also a lot of economic nationalists in China too.

When the US hits them with tariffs, China does something Japan never did in the 1980s. They counter-retaliate, imposing tariffs on US goods. That’s exactly what China has done today in terms of buying soybeans and other products as well. They’ve increased their tariffs on US products and we’re in this trade war with China in a way that we never really were with Japan.

Japan never retaliated against the United States. The US-Japan trade conflict really faded by the early and mid-1990s when Japan’s economy began to flatline a bit. It remains to be seen what the end game is with China because they’re certainly experiencing slower growth. Whether they’re ever going to really back down or whether we’re going to diffuse this conflict remains to be seen.

Jordan Schneider: Could you talk in particular about the trade policy response to Japanese semiconductors?

Doug Irwin: That was a big issue at the time and the concern was twofold.

Japan had this tendency, in certain narrow product categories, to ramp up its exports very quickly, in a way that really surprised and hurt big US domestic industries. Autos is a classic case of that. Imports from Japan in the late 70s, early 80s, began to skyrocket.

The same was happening with semiconductors in the mid-1980s. They were investing a lot in the production of DRAMs (dynamic random access memory chips), basic memory chips in computers. They were just pushing the US industry out of that product category.

Many people thought that the whole US high-tech sector would suffer as a result and we wouldn’t produce any semiconductors. What happened as a result of that competition is Intel and others started producing more microprocessors and specialized chips rather than generic memory chips.

What the Semiconductor Industry Association wanted was two things. One, they wanted Japan to stop — what they were alleging was — the dumping of chips on the world market. Second, they wanted to open up Japan’s market to US-made semiconductors. The trade conflict in 1985-1987 centered around those two issues.

An agreement was signed in 1986 where Japan agreed to stop the dumping. Otherwise, the US could impose these special tariffs. There was also a secret side letter to that agreement where Japan agreed to ensure that 20% of semiconductor purchases in Japan would be to foreign vendors. That was a secret because it was a market share target. There was some trade barrier preventing Japan from importing semiconductors.

It was thought that, through various administrative practices, the Japanese semiconductor market really wasn’t open to foreign competition. They set up this market share target, which was eventually hit in the early 1990s. The failure to hit that target was one of the rationales for the US retaliation for noncompliance in terms of that agreement with Japan in 1987.

Semiconductors are not really remembered as much today in terms of the trade conflict. It was a big issue with Japan in the late 1980s.

This is something that comes up time and time again in US trade policy history. At any given point in time, there's going to be one issue which is considered overridingly important. All attention is focused on it. As little as five years later, it can be completely off the radar screen of trade policy officials.

Everything’s on Japan and semiconductors in 1987, but by 1992, it was basically almost a non-issue. That tends to happen a lot. There are a lot of these fads of trade policy concerns or trade policy issues that really just die away with time.

Jordan Schneider: They die away with time and die away with changing macroeconomic flows. As fear of Japan recedes and the real estate bubble bursts, and the stock market bursts with it, then it’s not so scary anymore that Japan’s semiconductors may be taking over the world.

Doug Irwin: Exactly.

NAFTA, the WTO, and competitive liberalization

Jordan Schneider: Now let’s come to NAFTA, which was almost not a priority for Clinton. Time and again, we see the influence of elite, worldly policymakers. Lloyd Bentsen of “You’re no Jack Kennedy” fame ends up talking Clinton into it.

Tell that story and talk a little bit about NAFTA’s path through Congress.

Doug Irwin: One of the themes of the book is that trade politics is always partisan. There are always parties that disagree over trade policy.

Generally, NAFTA, which had been proposed by Mexico, was supported by Republicans and George H. W. Bush. It was more opposed by Democrats who were concerned about the impact on US labor and things of that sort.

Ross Perot ran for president in 1992 against NAFTA. The Democrats were generally considered to be skeptical about NAFTA but it was also considered to be very important in terms of foreign policy. Here is a sort of economic rapprochement with Mexico, a country with whom we’ve had difficult relations for many decades. It would be hard to reject it out of hand.

Clinton was a New Democrat who supported globalization and wanted to support NAFTA. Many of his advisors, however, were skeptical about it. He was a bit cagey during the 1992 election campaign. He really wanted to support it. Many of his aides early on in his administration were saying, “This is going to divide Congress and divide your party. You really don’t want to push this and you want to delay it.” They did negotiate two side agreements on labor and the environment to make it more palatable to Democrats.

At some point, like with many trade policy decisions, you have to make a decision. There was this meeting of economic officials in the Clinton administration. The Secretary of the Treasury, Lloyd Bentsen — a Democrat who supported more trade with Mexico for economic reasons and foreign policy reasons — banged his hand on the table and said, “we got to stand up and support this. This is the right thing to do.”

That got everyone’s attention. He was held in high esteem by the president and other members in the White House. That pushed the decision. Yes, we’re going to back this thing and we’re trying to get it through Congress. It was quite difficult for a Democrat president to go against most Democrats and try to get it through Congress. President Clinton, to his credit, did it in 1993.

Jordan Schneider: It was a tough fight. Bentsen said, “it was pretty touch and go.” Lloyd Bentsen at one point said, “I courted some of these congressmen longer than I courted my wife.”

Doug Irwin: That gets back to that point.

When you're in the executive branch and you're negotiating these trade agreements, you're negotiating with two parties. One is the foreign countries that you're trying to deal with and the other is Congress and its domestic politics.

It was actually easy to come up with a trade agreement with Mexico. That wasn’t a hard negotiation. The hard part was convincing members of Congress to vote for it because trade politics is always difficult in Congress. There’s going to be a lot of opponents.

The people who are going to lose their jobs in the industries because they’re going to face foreign competition, they know that and they’re going to fight it tooth and nail. Whereas the beneficiaries, the consumers or other export industries, are much more diffuse and widely spread. They’re not as politically engaged or active as those who are going to oppose it. It took a lot of persuasion and arm-twisting to get Congress to approve NAFTA.

Jordan Schneider: At least in the age of globalists, which we can maybe start from the early nineties, it does seem like trade has a particular grasp on the imagination. People maybe give it more weight than the economics indicate.

You mentioned this idea of national security being a key factor in American trade policymaking. Can you expand on that a little more?

Doug Irwin: National security has always been in the backdrop of trade policy discussions, right back from the very beginning. One of the rationales for early tariffs in Alexander Hamilton’s famous “Report on Manufactures” in 1792, was that we need tariffs to be economically self-sufficient in certain areas. We can fight wars and not depend on imported war material. It’s always been there. It’s never been a primary concern because the US has never really faced big threats of invasion.

During the Cold War when we were engaged in this conflict with the Soviet Union, there were provisions put in US trade law allowing the president to restrict imports on grounds of national security. This was if imports were impairing an industry that was deemed essential for national security.

That’s something that the Trump administration resurrected in the case of steel. They’ve also proposed it in the case of automobiles, although they haven’t proposed exactly what measures they’d like to take.

It’s always been a concern there. There’s always been an option to subordinate open trade policies to national security concerns. There’s also this question of abuse and whether it really was the case that we need to limit imports of steel on national security grounds or not.

Jordan Schneider: Speaking of other countries being upset at US trade policy, talk a little bit about the WTO. You argue that it was actually Reagan throwing around America’s might using the Section 301 clauses that got the world united into creating something like the WTO in the first place.

Doug Irwin: Yes, and certainly the dispute settlement system of the WTO, which is a key part of it.

In the late 1970s and 1980s there was a growth of voluntary export restraints. There’s something called the multi-fiber arrangement, which is limiting trade in textiles and apparel. There’s a sense that world trade rules were being circumvented and countries weren’t adhering to their obligations under the GATT.

The US wanted much greater enforcement of the rules. If we’re signing these agreements and coming up with these rules, they ought to be enforced in some way. In the administration’s opinion, there was no good mechanism in the GATT to do this. They started using Section 301 to address some of these things. Other countries hated this because the US would decide if some other country was a fair or an unfair trader. The US would grant itself the right to impose sanctions if a country was found in violation of some provision.

Basically, other countries said we need a neutral arbiter to determine if trade rules are being adhered to or not. We have to take this away from the US. It can't be just for the US to do this unilaterally. The US could get away with it because we're a large country. Other countries are really dependent on our market access.

How would Costa Rica or Jamaica ever enforce its trade rights? They don’t have the economic power to impose sanctions and discipline other countries and threaten them to get them to change their trade policies. We need some sort of independent arbitration mechanism to make this happen.

The Europeans and others basically said, “We’ll create this dispute settlement system in the WTO context as long as you stop using Section 301.” That was the implicit quid pro quo.

Jordan Schneider: Any reflections on the PNTR debate and Bush’s unilateralism?

Doug Irwin: The PNTR debate was about permanent normalized trade relationships with China. It was controversial at the time, in 1999-2000. It allowed China to enter into the WTO. Recently the administration has raised questions about whether that was a good thing or not and whether we struck a hard enough deal.

There’s a re-litigating of that debate. Of course, the reason why is that China has become a huge economic power that’s created problems for American industries. There’s obviously a big rethinking of the US-China relationship.

The Trump administration thinks that we’ve been the loser there, so PNTR was a bad decision at the time. A lot of the former US trade reps have come out and defended that, saying that at the time we got the best deal we could and China actually gave a lot of concessions.

That’s just part of the trade policy debate, always second-guessing whether we got a good deal or not.

Jordan Schneider: On Bush’s unilateralism, this idea of competitive liberalization sounds good to me. It’s like a race to the top for trade deals.

What were the issues with it that actually turned trade into a much more partisan issue than it was pre-2000s?

Doug Irwin: Competitive liberalization was a phrase used by Robert Zoellick, who was the trade negotiator in the George W. Bush administration. It came about after the Uruguay Round that created the WTO. The idea was that the multilateral system wasn’t working so well in terms of generating new trade agreements.

To keep the system moving forward in terms of lowering trade barriers, we needed more bilateral agreements. That will put pressure on other countries to join up. You’ll get this wave of bilateral trade agreements that could help the multilateral system.

It ran out of steam by the late 2000s primarily because Congress became more reluctant to support them. It was forcing a lot of trade policy votes in Congress, which most members of Congress don’t like to do. The Democrats took over Congress, in 2006 or so. That put a damper on what the Bush administration could do.

The idea has something to it. You see what’s going on today in terms of the European Union and Canada and Mexico. The US has stepped back from trade agreements to some extent. These other countries and regions are really moving forward and pushing forward with more and more trade agreements.

There is this dynamic that’s going on. We see that with the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The US pulls out of it, but the other countries that are party to it continue moving forward with not just that trade agreement, but with other trade agreements with other countries as well.

There is something to the notion of competitive liberalization. Mexico, Canada, the EU, and others have really pushed forward on that.

Trump’s Trade Policy Pivot

Jordan Schneider: We've done plenty of shows about Obama’s trade policy so we’re going to skip forward to the present day. In your book, you end on an ambiguous note. You’re unwilling to commit to whether or not the Trump era is going to presage a real paradigm shift on the level of the Civil War or post-Great Depression trade policy.

However, you wrote a recent piece in Foreign Affairs with a former ChinaEconTalk guest, Chad Bown. You declare that even if Trump loses in 2020, “global trade will never be the same.”

What’s the right way to think about Trump’s current, as well as potential future, impact on American and global trade policy?

Doug Irwin: The reason why I was ambiguous in the book is because I actually finished the book in September of 2016. I sent it off to the publisher fully expecting that I’d be dealing with President Hillary Clinton and trade policy would be on no one’s radar screen. No one would care about the issue at all. The book would sink into oblivion and not receive any attention.

I did have a chance after the election to just write two or three pages speculating about what a Trump administration might bring. I tried to just speculate about where the Trump administration might take trade policy, whether we’d live up to the rhetoric or that was just overblown and not much would change.

The piece I wrote with Chad was a two-and-a-half-year assessment of the Trump administration in terms of trade policy. They have introduced some really big changes that cannot be easily undone. They fundamentally shifted where we are in terms of trade policy.

One thing he’s done is impose tariffs on imported steel. We’ve had steel tariffs in the past. There are some exemptions to them. We’ve also gotten rid of steel tariffs in the past. A new administration could get rid of these steel tariffs to repair relationships with other countries and to help out our downstream manufacturers who depend on cheap imported inputs. One can see that happening and that issue moves to the back burner.

Of course, the big one is China. That’s where what the Trump administration has done is much less reversible. By imposing these tariffs on imports from China, it becomes very difficult for any future president to get rid of them easily without reaching some sort of an agreement. It's going to be very difficult to reach an agreement with China. What the US wants them to do is essentially act like a market economy, open up and not have the government play such a large role.

Of course, that’s a fundamental contradiction in terms of where the Communist Party is coming from and the control it wants to have over the economy. I do see a more or less permanent medium-term breach between the US and China that won't go away even with a new administration. Some of the other things that we’ve had with trade friction with Mexico, and trade friction with the EU, a new administration can easily repair those relationships.

Jordan Schneider: We’ve gone through a lot of American history here. Any suggestions for budding scholars who want to take a deeper look into trade history? Where should they dig? What sorts of questions do you think are particularly relevant today that are worth deeper exploration?

Doug Irwin: There’s so much out there that’s interesting. Obviously a lot of historical parallels can be explored. You can do some deep dives on some particular negotiations or some particular aspects of trade, going way back to the colonial period and through the years since.

One area that could be looked at more closely is the foreign archives in terms of how other countries have made adjustments to their trade policy, either in relation to the United States or just independently. We can shape more of a global history of trade policies.

Jordan Schneider: After I get my seven languages down, we’ll definitely take you up on that one. Any other final thoughts?

Doug Irwin: Just that it is amazing how there are these cycles in terms of how important trade policy is in American economic history.

It’s interesting to be present during this period now when trade is very much in the headlines and in the news, even if the news isn’t always good news.

Jordan Schneider: Oh to be alive in 2019. Doug Irwin, thanks so much for coming on ChinaEconTalk.

Doug Irwin: You’re most welcome. Thank you.

Doug never mentions how the USA was to a lesser extent but still nonetheless trade illiberal in its domestic economy in terms of its interstate trade for the first 200 years of its existence and it worked great for us. In the case of banking/finance/ monetary the USA was actually far more interstate protectionist for the first 200 years of our existence until it was dismantled during the advent of the so called Neoliberal Era (although a few pieces of it stuck around until the late 1990s) and that was a mistake for us to do that, the old system worked great!

Doug, Jordan,

Ok, you guys gave your globalization democratic liberal Chicago School side of the tariff debate.

Jordan can you bring the other side of this debate onto your show. There are a lot of things Doug said that many many would disagree with. His politics sticks out so blatantly. There is so much he said that can be refuted it's ridiculous.

Be fair to your readers and followers here. Playing politics is too important here to be doing.