Commerce released its much-anticipated chip export-control updates earlier this month. To discuss, I was joined by Dylan Patel of SemiAnalysis and Greg Allen from CSIS. We were not impressed.

Below is part two of our discussion. We get into:

Dylan’s and Greg’s pitches to incoming Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick.

Why America’s “scalpel approach” to chip controls backfired and what a “shotgun approach” could look like.

How China’s focus on trailing-edge chips and power semiconductors creates vulnerabilities that current controls don’t address.

How Trump’s team could use novel tariff strategies to turn China’s massive chip buildout into “ghost fabs”.

Click this link to listen to the show on your favorite podcast app.

And a job post! ChinaTalk is hiring for a dedicated China AI lab analyst. Chinese fluency and a technical background are required. Apply here!

Okay, Trump — Your Turn

Jordan Schneider: We have new regulations with significant gaps [discussed in depth in part 1 of our conversation], and a new president arriving in four weeks. What should Trump and his team do on chips? And what do you think they will do?

Greg Allen: Marco Rubio, our presumptive Secretary of State, has consistently criticized the Biden administration’s export-control packages as too lenient, citing numerous loopholes and oversights. While the Commerce Department leads on dual-use technology export controls, the State Department participates in the interagency decision process.

Rubio’s passion for addressing Chinese technology threats could make him an influential voice in this arena. Similarly, the incoming national security advisor, Mike Waltz, prioritizes Chinese technology competition. The Biden administration established this new approach to the Foreign Direct Product Rule — a tool now available to the US government. The Trump administration might wield this tool quite differently.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s revisit our strategic premises, particularly regarding allies and partners. Trump’s negotiation style with allies differs markedly. The irony would be if Trump confronts allies over minor issues like Mexican auto imports or Canadian timber while overlooking semiconductor manufacturing equipment — the EU’s primary export to China and Japan’s second-largest.

If Trump takes an aggressive, unilateral approach, allies might accept semiconductor restrictions while focusing on larger concerns like NATO’s stability or US troops in Okinawa. The impact on industry follows similar logic — these restrictions won’t collapse American, Dutch, or Japanese economies.

The crucial question becomes, “Do we abandon end-use controls for a nationwide approach?”

Should we implement straightforward restrictions on sub-300mm semiconductor equipment exports to China, eliminate servicing allowances, and replace 200-page rulebooks with five-page directives?

Greg Allen: The Trump administration initiated our modern semiconductor export control approach — from chip-level restrictions with ZTE to the Foreign Direct Product Rule affecting Huawei and TSMC, and equipment export controls involving Dutch EUV machine licensing. The question is whether they’ll follow this strategy to its logical conclusion.

No apology to China would dissuade their pursuit of domestic self-sufficiency and indigenization. They’re fully committed to this strategy regardless of any potential trade deals with Trump. The distinction lies between appearing tough and implementing effective policies.

Regarding countrywide export controls: they’ve proven unambiguously most effective among our policy iterations. The current 200-plus pages of regulations create enormous complexity for future negotiations. Simplicity benefits both companies and allies in understanding these policies. While I appreciate the nuanced logic behind these complex distinctions, countrywide controls offer valuable simplicity.

Dylan Patel: The real question is exactly what Greg said: “How tough will they be on China?” While they initiated these measures, they ultimately relented with ZTE. They didn’t follow through completely, allowing ZTE to survive and continue growing. The core question remains.

Banning 300-millimeter equipment seems like an extreme measure. Perhaps they’re just accelerating the tightening of restrictions. Most people presume they’ll take a tougher stance — they’ll certainly appear tougher, but the extent remains uncertain. If they were to ban all 300-millimeter equipment, it would completely halt the Chinese equipment industry, though such a drastic step seems unlikely.

Jordan Schneider: Different question. If you had half an hour with Howard Lutnick to pitch the right export control policy, what would your key points be?

Dylan Patel: First, don’t listen to tool company lobbyists — they’re motivated to maintain loopholes that allow them to continue selling for another year, worth over $5 billion to them.

Regarding tools being multipurpose: should we maintain the 14-nanometer logic threshold? Even above that, China has achieved significant indigenization in their military equipment, which the US lacks. Is that the right boundary? Moving it to 28 nanometers would eliminate many dual-purpose equipment issues. At 14 nanometers, some 20-nanometer equipment might work for 7-nanometer applications.

We must consider China’s breakthrough innovation capabilities. They’re developing interesting technologies beyond EUV. We could restrict these areas — for example, Zeiss lenses to China face minimal restrictions. Looking up the supply chain is crucial because even if China achieves breakthrough innovation in tools, they’d need to replicate entire companies like Zeiss and others across the industry.

Understanding the primary goal is essential. If it’s slowing China’s AI chip development to limit their economic and military projection power over the next decade, there’s much more to address beyond AI chips, though they remain the primary focus. The strategy should be tactful — ban subcomponents first, then tools at a lesser level, followed by chips at an even lesser level. This framework still needs refinement.

South Korea presents a crucial consideration, particularly regarding Samsung and SK hynix’s large Chinese facilities. We need their alliance while preventing IP transfer from their Chinese operations. Perhaps CHIPS Act 2.0 could provide significant support to Samsung and SK hynix in the US.

The diplomatic approach with South Korea requires more finesse than with the Netherlands. Dutch companies only make tools and rely heavily on US supply chains — while Korean manufacturers like CMS rank seventh globally in tool production. Their fabs lead in certain areas with significant Chinese capacity. We can’t simply impose blanket bans without considering the implications for Samsung.

Closing loopholes seems straightforward, but the strategic objectives and precise targets require careful consideration.

The current strategy resembles a jigsaw puzzle. Give a hundred-piece puzzle to an eight-year-old, and they’ll complete it. Remove one piece — they’ll still figure it out. Take away ten pieces — it becomes much harder. Remove fifty pieces — they can’t finish it. Remove all the edges — they’re completely stuck.

Right now, the strategy involves removing just a few puzzle pieces.

Greg Allen: And they’re doing it one at a time, giving China time to stockpile.

Jordan Schneider: Not to mention announcing it in Reuters six months before removing the puzzle piece — saying nothing of listening to Gina Raimondo’s phone calls. It’s all publicly available outside of paywalls.

Dylan Patel: This strategy is clearly failing. They remove a few puzzle pieces, but China responds by stockpiling equipment, accumulating HBM, buying subsystems, and dedicating significant engineering resources to solve each banned component.

Take high-aspect ratio etchers for 3D NAND: because the ban was telegraphed, they purchased substantial Lam Research equipment beforehand, including years of spare parts. They positioned new tools beside foreign equipment, analyzed the data from both, and now YMTC is close to developing domestic high aspect ratio etchers. The quality might not match Lam Research, but it’s progress. This happened because the 2022 restrictions for 3D NAND only removed one puzzle piece.

The key insight is that you need a shotgun approach, not a scalpel. If you precisely target one linchpin technology, they’ll solve it with their substantial engineering talent, capital, and industrial base. A shotgun approach increases both cost and time requirements — if you force them to simultaneously solve ten different technologies, splitting their engineering resources, they’ll advance more slowly and fall further behind in AI development.

Jordan Schneider: The irony here is fascinating:

If you sell them the complete puzzle, they won’t learn to manufacture pieces — there’s no incentive.

With a shotgun approach, they might decide it’s too challenging and redirect resources to other sectors like EV batteries.

However, America’s current approach of leaving enough scaffolding actually creates the perfect industrial-policy scenario. Companies typically avoid researching existing technologies when ROI is low, but the Swiss-cheese nature of restrictions over the past two years keeps them in the game, pushing indigenization further than if the US had either implemented dramatic FDPR in 2022 or continued selling everything.

Greg Allen: Say you and your spouse are choosing where to build your house: you’ve selected the neighborhood, but are still debating which side of the street. The dumbest thing you could do is compromise and build your house in the middle of the street. You can make logically consistent arguments for selling almost everything or almost nothing to China. The illogical approach is telegraphing your intention to restrict China while leaving numerous loopholes that undermine the strategy’s effectiveness.

These policies emerge from political compromises, which can be problematic. However, the “sell everything” scenario wouldn’t have ended well either. We sold everything regarding solar manufacturing equipment, and China now dominates that industry. The same happened with electric vehicles. Chinese policy documents and industry patterns don’t support the hypothesis that unrestricted semiconductor sales would have yielded positive outcomes. At this point, we’re committed to the export control strategy — we need to implement it effectively.

Jordan Schneider: Let’s create an alternate history. Up until October 2022, we sold everything to China. Huawei controlled one-third of global market share while Apple struggled in China. Meanwhile, SMIC was approaching competition levels with Intel, TSMC, and Samsung...

Dylan Patel: In this alternate history, Huawei had unlimited purchasing power until the Trump administration implemented restrictions. Huawei became TSMC’s largest customer and dominated Apple in the Chinese phone market. They emerged as the world’s largest phone manufacturer — not quite as profitable as Apple, but they were getting there. They dominated global telecom equipment markets, only facing resistance in regions where we explicitly banned their equipment due to security concerns, despite their technical superiority.

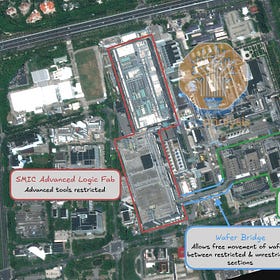

When companies have unrestricted purchasing power, they overtake industries. Take SMIC, for instance. With unlimited access to resources, they achieved 7-nanometer technology independently. Even though they could access TSMC’s 7-nanometer technology since 2018, SMIC still developed their own capabilities and found a market for it.

Their capacity today would be significantly larger without restrictions. Consider NAURA before the October 7, 2022, restrictions. Why did they maintain hundreds of millions in revenue when Applied Materials and Lam Research could sell freely to China? Because China’s industrial policy focuses on replication and building domestic supply chains. In an unrestricted scenario, it’s like giving them the complete puzzle, which they then recreate independently. Now, we’re only withholding one piece, yet they’re still determined to complete the puzzle themselves.

‘We Must Decide’

Jordan Schneider: Final thoughts — what’s the “America First” argument for investing in domestic semiconductor industry while restricting China’s semiconductor development?

Dylan Patel: Making American chips great again requires more than just the current CHIPS Act. $50 billion barely scratches the surface — Intel alone spends $20 billion annually on R&D, plus additional capital expenditure. The current allocation represents less than one year of spending, with Intel receiving under $10 billion spread across multiple years.

The renewable energy subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act represents about the same cost as securing even 5% domestic market share in chips. The semiconductor industry, where we currently hold significant market share, requires proportionally less investment. Industrial policy must be implemented before we lose our competitive edge.

To maintain at least 20% market share in memory, advanced logic, and other sectors, we need to act now. The cost increases dramatically if we wait five years. Tariffs alone won’t relocate chip manufacturing since the focus should be on end systems and servers. Manufacturing servers should happen in places like Vietnam and Mexico.

We need industrial policy that encourages significant capacity development. Should TSMC allocate 15-20% of their leading-edge capacity here, or should we aim for 30-40%? This goal is achievable with modest additional investment relative to government spending. Companies like Samsung, SK hynix, STMicroelectronics, and Infineon should be manufacturing in the US.

The CHIPS Act focuses primarily on leading-edge technology. We need expanded funding for both leading-edge and trailing-edge technologies to counter China’s dominance in the latter. Between 2022 and 2025, China’s IGBT [insulated-gate bipolar transistor] capacity growth exceeds the world’s existing capacity. While their yields may initially be lower, they’re positioning to control 50% of global capacity in power semiconductors. This creates significant supply chain security concerns that require strategic industrial policy rather than blanket restrictions.

Greg Allen: My question regarding everything you said is that Donald Trump considers himself “tariff man” and loves tariffs. The current tariffs on Chinese semiconductors apply only at the chip level when shipped as standalone items. While it would be complex to apply tariffs to the component value of chips in finished goods, it’s not impossible.

I’ve been wondering if the Trump administration might say that they don’t want what Trump has called “corporate welfare” through the CHIPS Act. Instead of industrial policy through subsidies, they may prefer industrial policy through tariffs. The current tariffs on Chinese semiconductors aren’t effective, but a different approach to tariffs might work. Though I’m not certain this is what they’ll pursue, it seems consistent with their messaging.

Dylan Patel: The question is, “Are you going to tariff electronic systems manufactured in China? Are you going to tariff 90% of iPhones?”

Greg Allen: We’re entirely speculating here, but I think they would say if an iPhone contains Chinese chips, the tariff applies based on the value of those Chinese chips. We’re always tariffing chips, whether they arrive in a box labeled “chips” or in telecommunications equipment.

Dylan Patel: Presumably it would be tiered — Chinese chips at a 500% tariff and Taiwan chips at a 10% tariff.

Greg Allen: Exactly. All this Chinese legacy buildout we’ve discussed — some of which might be advanced node production disguised as legacy node — could become the industrial equivalent of those ghost apartment buildings in China. If there’s no end market for these Chinese semiconductors, their industrial policy would be a disaster. They would have built a bridge of subsidies to nowhere. While I haven’t heard from Howard Lutnick or others in the Trump administration that this is their planned policy, I could see this approach being attractive.

Dylan Patel: But if you want to prevent China from gaining global market share in trailing chips outside of China, the primary task is moving electronic manufacturing out of China. The US market share for most products — excluding high-end AI servers — is only about 30% to 40%. For AI servers, it’s around 70%. We can dictate policy on AI servers, assuming we resolve the data center shortage, which requires significant regulatory changes.

Greg Allen: You’d have to persuade Europe and Japan to participate.

Dylan Patel: Exactly. Otherwise, why wouldn’t Xiaomi phones — which hold 20% global market share — and other Chinese phone makers like OPPO simply use Chinese RF chips, power management ICs, and antennas? They clearly will, unless we can move both manufacturing and vendors out of China.

Consumer goods, especially phones, are dominated by China. For laptops, you’d need to convince Dell and HP — through their ODMs [original design manufactures] like Compal — to completely relocate to southeast Asia, India, or elsewhere. A tariff on chip value made in China doesn’t solve this issue.

Since we’re speculating about the Trump administration’s approach, why not be more heavy-handed? We could tariff everything shipped from China, with lesser tariffs on Taiwan and southeast Asia. This would make moving out of China a massive cost saver — perhaps not enough to justify Mexico, but definitely southeast Asia.

Greg Allen: We’re at a point in the story where the Biden administration has assessed the policy toolbox created by the first Trump administration. Now we’ll see how a second Trump administration utilizes the toolbox Biden’s team has created. While some people in DC — certainly not me — may be tired of the semiconductor and AI great power competition narrative, I don’t think it’s going anywhere. This will remain a significant part of geopolitical competition and a key focus for the Trump administration.

Jordan Schneider: I got one more riff.

The intellectual- and execution-level challenges the Biden administration encountered with export controls exemplify broader Democratic Party challenges. There’s a tendency to believe they can devise the perfect algorithm that balances all competing interests. They think with solving enough integrals, extensive legal review, and track changes on docs, they’ll reach the optimal solution.

This pattern emerged with the Inflation Reduction Act’s lengthy development, the CHIPS Act’s extended negotiations, the periodic reassessment of Ukraine arms distribution, and these export controls. The problem is that, if you can’t make tough strategic decisions upfront and execute them — accepting that not everyone will be happy — you end up in limbo. You achieve worse results by trying to moderately satisfy five variables instead of maximizing the two most critical ones.

Greg Allen: Another way to put it: faster and good enough is almost always better than slower and theoretically perfect.

Jordan Schneider: As a new American dad returning from paternity leave, I’ve been exercising by birthright by reading Civil War history. There’s an excellent quote from Colonel James Rusling’s memoir about how Grant made decisions.

The irony is that October 2022 really felt like a decision point. Jake Sullivan gave a dramatic speech stating we needed to stay as far ahead of China as possible in critical strategic emerging technologies. A month later, ChatGPT emerged, clearly demonstrating AI as the critical emerging strategic technology. They were onto something, but now we’re left with this muddle.

Part 1 of our conversation:

Biden’s Final Export Control Salvo Misfires

Commerce released its much-anticipated chip export-control updates yesterday. To discuss, I was joined by Dylan Patel of SemiAnalysis and Greg Allen from CSIS.

You guys are assholes. Casually talking about impoverishing 1.4bln people. Almost 20% of the world population.

And also if you move industries to other countries it’s still the same reliance of the USA on still OTHER countries. Is it the ethnicity of the number 2 economy that’s so unpalatable to you people? There’s a word for this: racism. This has nothing to do with the CCP. The direct effect of tariffs will be more jobless Chinese citizens. Very productive indeed.