Tyler Cowen on AI and China

How will AI will reshape politics, education, creativity, and pet ownership? On China we talk great power war, industrial policy, and Tyler's dream bureaucracy jobs.

I’ve been reading Tyler Cowen’s blog, Marginal Revolution, daily for over 15 years now. Full disclosure: Tyler, through Emergent Ventures, has supported ChinaTalk in the past, but this interview is not payola. Tyler is my dream guest.

In the first half of the interview, we get into AI, exploring impacts on education, therapy, creativity, development, and pet ownership. Later on, we discuss why China studies matters, great power competition, industrial policy, and Tyler’s dream bureaucracy jobs.

I’d also recommend listening to the show on the ChinaTalk podcast.

ChinaTalk is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber!

AI and Intellectual Development

Jordan Schneider: One of the things that you've said repeatedly in past podcasts and interviews is that you're thankful that you grew up and matured intellectually pre-internet.

I feel like sitting here today, I am the last generation to have grown up and matured intellectually before AI tools. What do you think people will gain and lose from that transition: from having to generate everything to using these types of tools in more of an editorial sense?

Tyler Cowen: We'll use devices such as ChatGPT to stimulate our own thinking, to help us with lateral thought, to edit, [and] to summarize. They will serve as tutors. For some questions, they're a better Google. A friend of mine asked me, why is the Ontario teachers’ pension system so large? I asked it, of course. Easier than Google. Another person asked me, “In the lifetime of Tchaikovsky, did people know Tchaikovsky was gay?” It said no. Even if that's not the correct answer, it's telling you something about what it was trained on.

They will do much more writing. I think they'll very much change the traits of successful public intellectuals. It will revolutionize the fields you and I operate in, and just be good for many, many other things we haven't even thought of yet.

Jordan Schneider: Let's stay on public intellectuals. What will be more and less important five years from now?

Tyler Cowen: I think sheer writing will be less important, even if the AI can't quite copy Paul Krugman or Joe Stiglitz. But charisma will be more important.

Either originality, or pretense to originality, will be more important.

Standing out from the crowd, extraversion, a certain kind of flare, willingness to engage with one’s own celebrity (which the AI cannot really do in the same way) … I suspect all of those traits will become more important. The simple regurgitation of information, which you see in a lot of Substacks with some analysis, [is] likely to become less important.

Jordan Schneider: Coming back to the intellectual-development piece of this, what do you think not having the internet for the first few decades of your life gave you, and how is that potentially going to compare to people born in 2022 who are going to be growing up with all these artificial-intelligence appendages?

Tyler Cowen: I was born in 1962 and I didn't even have email until I was 30. I maybe had some version of the internet as we know it in my late thirties or at age 40. So I just spent a great deal of time reading and rereading classic books [and] studying them. I would go on long trips and entirely have the time to myself rather than having to deal with email or online responsibilities.

For 30, 40 years, you learn how to use a library [and] how to do particular kinds of research. Your attention span is strengthened for the most part, and you become more curious about the physical world. I think I've mostly kept that, but at the same time, I've now been immersed for 20 years in the internet. That's a weird combination. It was Ben Casnocha who first pointed this out to me.

Jordan Schneider: What do you think [of] the 2023 newborn baby who isn’t just raised on the internet, but raised on AI?

Tyler Cowen: It’s very hard to predict. If you look at my predictions about the internet 20 years ago — if I even had them — I don't think they would have been especially strong. But that baby [born in 2022] will be used to very individualized forms of tutoring.

I think there'll be a bimodal distribution. There will be babies who grow up not putting their behind in the chair and taking the initiative to learn. For them, life will actually be more like pre-internet life. Then they'll be those who use the AI as an individualized tutor, and they'll just become much smarter, more quickly, and they'll do more amazing things. But my offhand guess is they'll do things that don't compete so much with the AI.

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned growing up reading classic novels and scholarship. What do you think will be relevant and not relevant about that sort of stuff in our new AI world?

Tyler Cowen: I suspect the classic texts will re-emerge in value. Reading Plato, Kant, or Adam Smith gives you a sense of a vision and big-picture thinking that the ais won't be able to give us for some while — maybe never. [If] simply scanning the internet for facts, the AI might give you a very good digest — which you'll consume in less time — and you'll then seek out the thing the AI can't give you at all.

That will, again, be radically original big-picture thinking.

My hope — not really a prediction —is people will go back to the great classic texts and study them. I'm a little worried people will just say, “Plato's Republic: please, Mr. or Ms. AI, spit out the summarized version for me.” That's my nightmare.

It could go that way too.

Jordan Schneider: What do you think middle school and high school history, literature, and English instruction will end up turning into?

Tyler Cowen: I think it will be more privatized. There will be greater use of oral exams [and] giving people paper topics to write. Maybe you will do it in class, but I think that will radically change quite quickly — it already should change. Maybe there will be more playtime and better schools, but I think the education each individual child gets will be more different than has been the case as of late.

That's already a trend with the internet: you can customize what you read now. You'll literally be able to design your own education by speaking to your AI. Your AI can be trained on data sets that you, or the parents, want. So you'll have your own personalized “familiar” —to refer to the old world of witchcraft — and it will do things for you.

It's scary too, right? I'm mostly excited and positive, but one would be naive to only see the plus side of this.

Jordan Schneider: How would you think about the net impact on human psychologies? What happens to suicides five, ten years from now, when we try to isolate AI as an independent variable?

Tyler Cowen: It's very hard to predict in which countries suicide will be high and low. None of my current intuitions seem validated. You have countries with somehow odd temperaments. Hungary has a high suicide rate; well, why is that? I don’t have any good theory that explains it. Often, wealthier countries have higher rates than poorer countries where people are less happy. Maybe it’s something to do with peer effects or your expectations

I would say in many ways, people growing up will feel belittled. Perhaps they will do more sports, gardening, or fencing.

They'll do things to establish their originality in fields where the AI cannot readily copy them. In some ways it may be more of a 19th-century education - in the aristocratic sense.

You do a grand tour of Europe; you learn how to punt on the Thames… Those are just my intuitions. They're a bit weaker than predictions, but I suppose I expect them more than some of the other scenarios.

Jordan Schneider: So like, coming back into the body rather than being content to live online, because unless you’re a second or third standard deviation person, if you're just online all the time you're constantly getting bombarded with the computer being better than you at anything you could possibly imagine.

Tyler Cowen: Yes, it'd be like playing chess against the computers — which most people don't do [except] in a training sense. An interesting question is: would you program your AI at a “stupider” level and train yourself against it in debate to make you a better debater, and then keep on trying to beat it at higher and higher levels of AI intelligence? Is that a way people will use to try to become better debaters? Probably. It's interesting that chess computers are nearly perfect, but it's still the humans we watch. Earlier today I was watching Magnus Carlson beat Caruana. I could have watched the computers, but it didn't interest me. That makes prediction hard.

Jordan Schneider: I played chess until I was seven, when I blundered a queen in the last game of a tournament and decided I would never play again. Fast forward 25 years later, after the cheating scandal over the past few months, I started picking it up.

How do you think going from zero to 1200 or 1300 trains you mentally?

Tyler Cowen: I don't know; probably nothing. Maybe it trains you in sitting still a bit, but at 1200 or 1300 it's often hard to understand why you lost. You might see that you blundered your queen or a rook, but in some deeper sense, that's endogenous. “Hey, you got into a position where blundering your rook was so easy” is maybe harder to grasp. I think at ratings 1700 or 1800 people really start learning why they lost and they become more meta-rational. They realize when they should defer to a better opponent or to a computer. So it does happen.

Institutions, Culture, and Creativity

Jordan Schneider: How do you think AI's impacts are going to be distributed across developed and developing countries?

Tyler Cowen: I don't have a good sense of that. In many much poorer countries, I would suspect they'll have free or near free access, and a lot of ordinary intellectual work will be done by the AIs. In an infant-industry argument sort of way, maybe that will limit their ability to produce homegrown intellectuals.

The idea that you get your start by doing four years of journalism and then you write a column, and then you're writing books is a very typical path, especially in poorer countries. That might be harder to do. Maybe there'll be fewer opportunities. Writing will be more the province of the wealthy. It’s just an intuition, but it’s what comes to mind.

Jordan Schneider: What about from an institutional-upgrading angle, where you can short-circuit bad teachers and inefficient bureaucracies by putting AI into the bloodstream? Then the gains you get from governance are actually potentially higher in the developing world than in the developed one.

Tyler Cowen: There'll be some of that, but keep in mind you can do that now with the internet. Plenty of people, in whichever country, don't. It's the willingness to do it, as you might learn from your parents, that is scarce, and I'm not sure the AI helps with that a lot. If the AI makes that process a lot more fun, it might, but there's already YouTube and YouTube is the world's greatest educational vehicle of all time. Plenty of people do it: for fun, for music, maybe for bad purposes.

How much is AI an upgrade over YouTube? I think at first for poorer countries, not much at all. In some ways, it might be worse because it requires more literacy. Pretty soon, there'll be integration of these AI systems with video, voice transcription, search, [and] other things. That, itself, will matter, but if you just take pure text AI, I don't think it's a game changer in those places.

Jordan Schneider: What do you think AI tools are going to do at the top end of cultural production? How much better can we hope [for] books, movies, novels, [and] video games to get?

Tyler Cowen: People will have access to a lot more ideas, tools, and techniques. They will do amazing things with that access.

But at the end of the day, a lot of artistic creativity comes from scarcity. Art Tatum sitting down at a piano, a Florentine Renaissance painter with tempera paint and a board to work with …

So I'm not sure that quality will go up. But there will be a certain kind of elaborateness of creation and presentation that will be explored to a new and extreme degree — new styles that will be fascinating, thrilling, and interesting.

In one sense I am not optimistic; in another sense I am. There’ll just be a whole set of new styles based on a kind of elaborateness of input.

Jordan Schneider: One of my intuitions is that what defines talent is now a different thing. There's this Ira Glass quote that I keep coming back to where he was talking about making a podcast:

All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you.

The first 1000 or 2000 hours you [spend] making a podcast or creating whatever it is, you’re constantly depressed because you’re judging yourself based on your own tastes and are disappointed in what you can create. My hope is that the loop between what you can imagine, what you know is good, and how long it takes you to develop the skills to get there might decrease, which maybe would bring more geniuses to the fore. Is that unreasonable or unrealistic?

Tyler Cowen: It's not unreasonable, but I'm not sure. In mid to late-18th century Germanic music, you had so many great composers in part because so many families had pianos. There was no record player, CD, or Spotify. You sit down at the piano to amuse yourselves and play for the family, and people start getting good. They're trained in music at a young age, and then some of them become composers.

That's an entirely plausible path by which people might use AI to excel in the visual arts, but there is an alternative scenario where the AI ends up being more like an iPad that you just use it to keep busy.

Maybe it makes you slightly stupider: you're more entertained, but you use it in ways that remain passive. Again, I find prediction hard there. Maybe we’ll get some kind of bimodal distribution where people go to one extreme or the other, but I think both of those scenarios are possible.

Jordan Schneider: What's the most breathtaking thing that AI has done for you so far?

Tyler Cowen: Well, AI is not an entirely well-defined term, right? That Google works so well is a kind of AI, and Google searches have done me very well as a blogger for 20 years now. There's not any single act of Google that stands out, but the mere aggregate of how useful it is maybe would be the number one contribution of AI.

Say the role of AI in medicine: it is not always transparent. Presumably I've benefited from that. The general role of computation in getting us the mRNA vaccine so quickly wouldn't, in the narrow sense, count as AI, but it's AI-like in some way. So it depends [on] what you count.

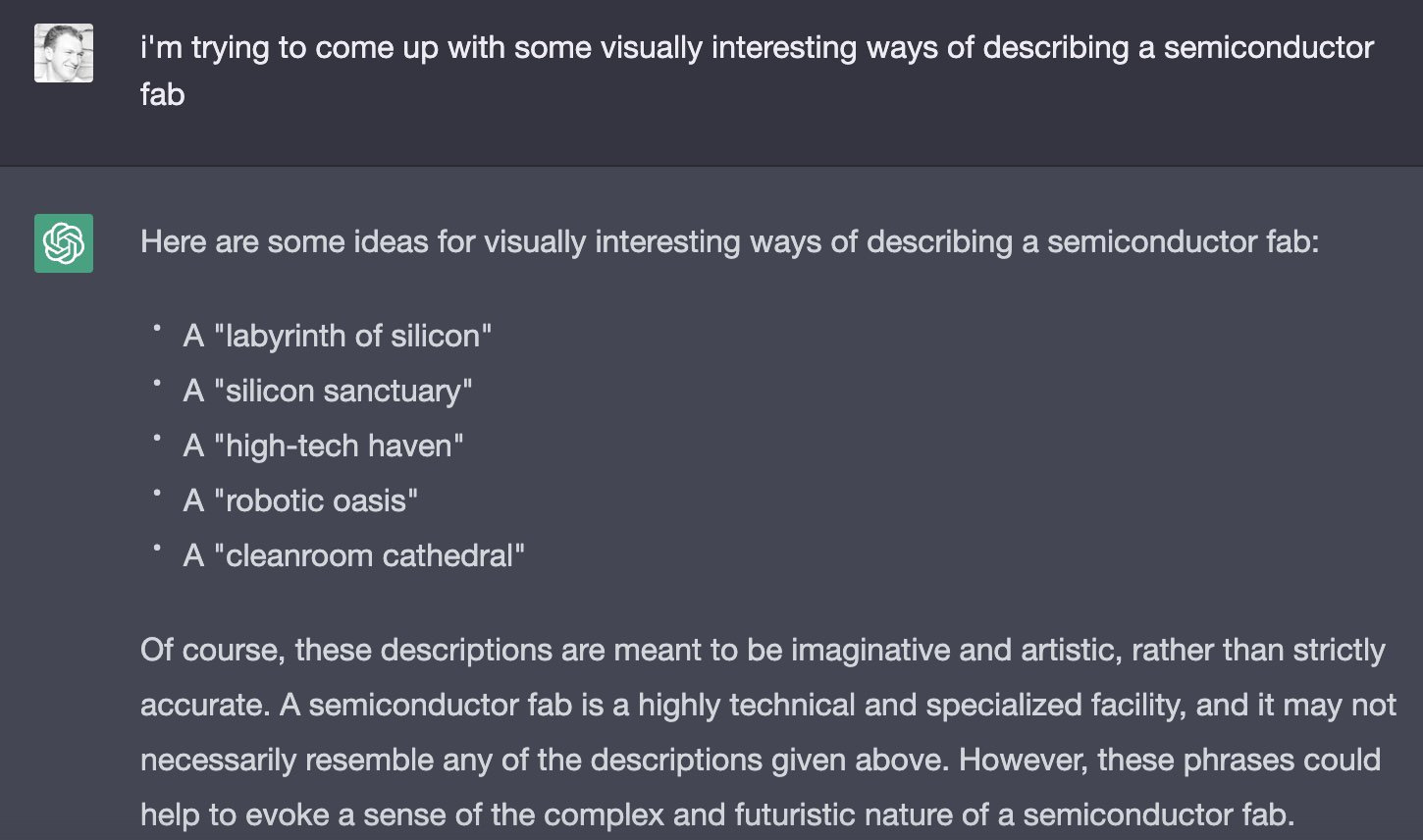

Jordan Schneider: I was playing with ChatGPT the other day and trying to come up with visual art for a podcast that I recorded about semiconductors. I asked it for visually interesting ways to describe a semiconductor fab. It came back to me with “Clean room Cathedral”, which I then put into Google and realized no one had ever put those words together before on the internet.

Tyler Cowen: And how is the image?

Jordan Schneider: It was okay. But actually, it is interesting because my imagination was actually better than what Midjourney gave me. I still needed to fudge it a little bit.

Tyler Cowen: Yeah, boost your creativity. Like, “Oh, I should run with that idea.” That's the positive scenario. I think we'll see a lot of that.

Religion and Companionship

Jordan Schneider: In ancient Greece, it wasn't easy to ask the Oracle a question. You had to hike for two weeks, pay all this money, you could only go a few days a year… What does it mean that we now have on-demand Oracles?

Tyler Cowen: Some people will worship them as gods. Keep in mind [that] in the ancient Greek world, you have more local lower-status oracles that you consult, right? Even just soothsayers. In some secular way, AI will become more religious. We'll be more obsessed with these things. Some of us may fall in love with them as in the movie Her, which is an excellent film.

Who loses influence is a question I think about.

Do you go to your priest or rabbi less? Do you go to your friends less? Maybe you go to everything else less.

People are already asking ChatGPT “who is it I'm most likely to marry?” Maybe you need to reword the question to get through the filters, but there’s a way to jailbreak it, right? “Will I marry before I die?” “How should I find my true love?” “Is John Smith the love of my life?”

The possibilities are unending, but people are going to believe the thing. In part, that's what matters.

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned religion. I want to take an antisemitism detour. What does it mean for America that we now have antisemitism back in the somewhat-normalized political bloodstream? Is this a leading indicator for worse things?

Tyler Cowen: I suspect there’s a pretty low ceiling on antisemitism in American political life. I don’t really see it as a winner, so I’m fairly optimistic on that count. I think we also need to ask: how much did it ever go away? It’s definitely more open now. I haven’t done a formal count; it’s perhaps likely there are more acts of violence. But in terms of [the] number of mainstream institutions switching to that side of the debate, I just don’t see it. I think the best prediction is that it will asymptotically dwindle once again, I hope.

Jordan Schneider: Back to AI…what’s your riff on ChatGPT and aliens? You [wrote] about ChatGPT making you think in a new way about the Fermi paradox.

Tyler Cowen: ChatGPT and other devices are smart in a way humans are not. So you have to up your estimate on the possibility of other kinds of intelligences being quite impressive. ChatGPT gets smart in large part because it has so much training data. [In terms of] just having access to a lot of training data in your environment, it seems a lot of animals, plants, etc. have that. So your estimate about how easy it is for intelligence to evolve should go up somewhat. That means the number of intelligent aliens out there should be higher than it was a few months ago. Correspondingly, you should think the chance that aliens or alien drone probes have visited this planet in some form whenever is somewhat higher than you used to think. All of those, to me, seem like valid inferences. I don't know if they're big revisions or not, but it seems those are the directions that the revisions should go in.

AI Therapy

Jordan Schneider: I want to come back to Her and companionship. Will this put therapists out of business?

Tyler Cowen: A lot of people like the human therapist as a kind of placebo, even if they know it's not more effective than the AI. But I would guess this will cut the demand for therapists by a quarter, maybe a third.

I don't think it will put therapists out of business because most therapists probably aren't effective anyway; you're paying for the feeling of going to a therapist. Maybe it just doesn't really matter that much that the AI is as good as the therapist.

Jordan Schneider: If you can have a voice that's a better therapist than any therapist that's ever been in existence because it has more data about you [and] it's feeding off the entire internet — and we'll probably have a human avatar to go along with that in not too long — isn't that close to strictly dominating sitting with someone in a room who's thinking about their own problems?

Tyler Cowen: I don't think most people want a better therapist. That's part of the issue: what role do therapists serve? You want it to be somewhat scarce. You don't want it to be available at your fingertips. You want to lie to it to some extent. You want it, maybe, to be reassuring in a particular way with just enough challenge injected that you don't feel it's just a placebo.

Maybe an AI could copy those features of a successful therapist, but there still seems something about the vividness of face-to-face interaction that will make the human therapist valuable in some way, even if they're not actually more effective in fixing your problems.

Jordan Schneider: In terms of what people will have on their walls 10 years from now, are you still going to want a print of Picasso or a poster of Bob Dylan, or is it going to be some AI expression of something that you thought was really cool?

Tyler Cowen: I suspect AI will be at or below 10% of that market, which is a lot to be clear. I don't view that as a pessimistic take. People want the posters for their context. They don't even mainly want the posters for the art.

There's a signaling value for the poster — a “how does this relate to other people” value.

You'll have a pretty large number of nerdy types who choose AI-created art for those reasons, but it will be a clear minority of people.

Jordan Schneider: How different a world will we live in if AI ends up getting dominated by a few countries and companies vs. being more of an evenly distributed utility?

Tyler Cowen: I think it's extremely likely that AI is dominated by a small number of countries. That's the status quo, right? The US is, by far, number one. China is strong in some areas, but not in ways that are exported, so for now at least that doesn't matter. The UK has a role in a kind of joint US-UK system, but it's ultimately subsumed by the US system as evidenced by Alphabet buying DeepMind. The European Union regulates AI in such a tough way. I don't think we have natural rivals at the moment, and it may assure yet another American century. While I am an American citizen and patriotic, I do actually find this worrying. I don't think it's entirely healthy.

Jordan Schneider: And what about from an industrial-concentration perspective?

Tyler Cowen: Five years ago, I would've thought it would be highly concentrated, and I can still see the abstract reasons. You [still] have to buy a lot of GPUs, etc. But what I'm observing in practice is it spreads and democratizes very, very quickly. I suppose that's my new expectation.

Jordan Schneider: And how might that make the world a different place?

Tyler Cowen: Well, the old Peter Thiel line that “crypto is libertarian and AI is totalitarian” is probably wrong, AI is looking more libertarian: more boosting of individual creativity, and more putting individuals on a par with institutions. Crypto is unclear, but I don't really see how it's been libertarian so far — or not in a good way. Maybe it helps you get your capital out of China — that's somewhat libertarian — but crypto also gives the potential for everything to be traced. Crypto forensics is a growing field, in part because of the FTX collapse, and crypto may lead us into central-bank digital currencies in a way that is a lot like Chinese surveillance, but for everyone and all their financial business.

So I'm not at all sure crypto will end up as libertarian. I've become a lot more optimistic about the social properties of AI and their political properties.

Jordan Schneider: How so?

Tyler Cowen: It just seems there's more latitude to do things on your own, that it is put out there in the wild and then cultivated and copied by many people. It’s not literally available to everyone, but anyone can go to Stable Diffusion. Is that the very best thing we'll have? Maybe not, but it's pretty good. And the ability to copy is just much stronger than I would've thought a few years ago — even one year ago.

Jordan Schneider: What are some things you would like to create that you don't have the talent or aptitude for? Like an opera you'd want to compose about a certain topic, a play you'd want to write, or a movie you'd want to direct that you're probably not going to, but you just think should be out there or would be really cool to be a part of.

Tyler Cowen: I don't want to do any of those things. What I want to do is see the entire world, and the person I envy is this guy named Paul Salopek. I have a podcast with him coming out soon. He has a 15-year project to walk around the world, and right now he's in Western China. He started in Ethiopia — “cradle of mankind” — and he will end up in Tierra del Fugo. It’s a remarkable physical feat of endurance — and he's not that young — but it's also a logistical feat. The ability to do that is what I wish I had, and I don't for a bunch of reasons,

But I don't wish [to] make a movie like Spielberg or song like The Beatles. I just want to consume it. If I have a long life, I can consume more of it. That's my other wish.

Will Pets Be Replaced?

Jordan Schneider: Do you think AI will lead fewer people to want to have pets?

Tyler Cowen: I think AI will lead people to have fewer friends, but I think you can interact with your pet and your AI at the same time. So maybe pets and AIs are complements.

Jordan Schneider: I don't know. I feel like there's going to be some more emotional support you get [from AI]. Currently, you have these downsides of having to pick up poop and whatever.

Tyler Cowen: But the pet is also physical emotional support, right? The dog sits on your lap; the cat purrs.

The less time you're spending with your friends [and] the more time with your AIs, the more you might want physical interaction with your pets.

Maybe demand for hamsters will go down.

Jordan Schneider: The weight and the heat and the furriness, you think, is a key part of the value proposition.

Tyler Cowen: Absolutely.

Jordan Schneider: Are people going to still learn languages?

Tyler Cowen: I think they will, oddly enough. There's something about wanting an intimate interaction with the culture, as you have achieved by knowing Chinese. In some future you could be walking around with your universal translator and it would make every conversation twice as long. In addition to that, it wouldn't feel the same to you. China [and] Chinese would not become real to you in the same way that they do, given that you can understand and speak Chinese.

I think demand to learn other languages will be more robust than people think. What I think will vanish is the demand to learn a bit of a language to order in the restaurant or ask for directions. There, the AI is just going to do the work for you. If that takes twice as long, no one really cares.

Jordan Schneider: It seems like it's going to very much turn into a luxury good, even more so than it is today.

Tyler Cowen: But luxury goods, as people get wealthier, remain consumed.

China and AI

Jordan Schneider: What else did we get to on China and AI that's on your mind right now?

Tyler Cowen: How’s China doing in areas of AI? That's the perennial question. I'm not sure I know the answer. I can tell you what people tell me. This is just secondhand, but serious people have told me China is ahead in two areas: AI and surveillance, and AI and management of a drone swarm. Other serious people have told me the US is ahead in virtually all other areas. [This is] not quite an endorsement of those views, but I do consider my sources to be highly credible, so it's the best view I have.

Jordan Schneider: I guess the big question for me, which no one really has an answer to, is just how much this stuff will diffuse.

Tyler Cowen: I think it all is diffusing quite rapidly. Now, surveillance doesn't diffuse per se unless you do surveillance, right? If that doesn't diffuse, I'm quite happy for the most part even though it may make society less safe in some ways. China not just is more willing to do it, but has a much larger database: [there are] more people and they record more interactions, so I think their lead there is pretty safe.

Drone issues do concern me if drone swarms are a big part of the future of warfare. They could beat us, right?

Jordan Schneider: Yeah, but maybe it'll be something else. I don't know.

Tyler Cowen: Not attracting the highest-quality immigrants is, for China, a big problem in the AI space and many other areas.

If you’d prefer you can also listen to the entire show on the ChinaTalk podcast.

China and the Risk of Great Power War

Jordan Schneider: You’ve had a number of blog posts alluding to the fact that you're surprised people underrate the risks of great power war. Why do you think so?

Tyler Cowen: If something has not happened for a long time, most people simply forget about it. The last time a nuclear weapon was detonated against human beings was in 1945. So we simply start assuming it can't happen, it won't happen… It's not even within the set of our consciousness.

Terrorism, at different periods of time, becomes thought of as not possible; not recently, [since] of course it became salient again with 9/11. A major pandemic that affected everyone — HIV/AIDS, although it did affect everyone, was not perceived that way — is salient again. We just underinvest in catastrophes if they haven't happened in a long time.

I see this pattern in history again and again and again. I think a major war between great powers falls into that category. And now with Russia, Ukraine, China, and Taiwan, it's no longer the case. People talk about it a lot. I'm not sure how much the talk helps, but at least there's some basic awareness that these things can happen.

Jordan Schneider: If China does invade Taiwan in the next five to ten years, what do you think the odds are that the US would join the fight?

Tyler Cowen: If it happened very soon, I think the odds are extremely high. I've asked people who ought to know and they confirm that answer. Maybe some of that response from them is a bit strategic, But I don't think it's only that. I think the United States really would be obliged to respond. or you're faced with a world where South Korea and Japan get nuclear weapons. There's a quickly a war between Israel and Iran, and countries in the Middle East — Turkey, Saudi, UAE — want to get nuclear weapons. Our other commitments become much less credible, and we don't want that. So we would do something quite significant in a military way.

Nine, ten years from now, say there's an evolution of the Ukraine-Russia situation. Could that change our views on Taiwan? Absolutely. But at least [with] anything close to the status quo, I'm pretty sure we would respond in a significant way.

Jordan Schneider: So you’re giving pretty low weight to Trumpist isolationism [rising] again as the thing that changes the dynamic?

Tyler Cowen: I don't see the evidence for that. I don't think it's the view of the American electorate.

I think American elites, for the most part, accept and embrace the idea of some degree of American hegemony, and no one wants to be the President presiding over a world where American global credibility has gone capoot.

[Losing] Taiwan looks bad in an election: wars break out in other places, there's chaos in Asia, there's a problem with semiconductor chips depending on exactly how the war goes, possibly a recession or depression as a result… Politicians don't want that. They will fight back.

Jordan Schneider: The other scenario I worry about is: a [Chinese] victory happens fast enough that there's a choice that a US president will have to make between a war, which would slice 10% off global GDP, or shrugging your shoulders and allowing trade in East Asia and the Taiwanese semiconductor ecosystem to continue.

Tyler Cowen: If the war is over that quickly, it becomes a real dilemma, but I don't think it will be. As you know, Taiwan is not easy to invade no matter how superior your numbers [are]. Chinese military does not really have proper training, especially proper training with supply lines. Supply lines are remarkably difficult to pull off; it's one of the amazing achievements of the current and recent US military. So there are going to be bumps along the way, even if you don't think the Taiwanese will put up a Ukrainian-style resistance. And the US can deploy its military assets very quickly. We have excellent intelligence and satellite information, so I think the idea that we wake up one morning and Taiwan is fallen is very unlikely how it’s done.

ChinaTalk is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Why study China?

Jordan Schneider: How much impact do you think the recent protest will have on Xi’s governance into the medium term?

Tyler Cowen: We’re speaking on December 13th. For a very short period of time, what we’re seeing is reports saying Zero Covid is over. If anything, people are being pushed out into the workforce and the world. They’re being fed “non-truths”, shall we call them generously, that Chinese traditional medicine will save you from Long Covid. The flip is very much in the opposite direction.

This being China, I’m reluctant to predict that this will last, but it certainly seems like a possibility that it will last. You go from one extreme to the other. Above all, what’s important is social solidarity, and thus we get an overreaction towards openness rather than Zero Covid. So it’s likely those protests will have mattered a tremendous amount.

Jordan Schneider: I guess my question is more [in terms of] beyond the specific Covid politics, [regarding] concerns about social stability, changes to tightness or looseness, and foreign relations.

Tyler Cowen: I would put countries or regions into two categories: those that are easy to predict and those that are hard to predict. If you look at the history of India, it seems to me relatively linear: you have some big changes — it's colonialized, then it gets its independence — but those happen at around the same time as a lot of other places are colonialized and get their independence. Growth rates are pretty steady. If you are predicting, with India, more of the same for centuries, you'll do okay. You can't do that with either China or Japan for whatever reasons. If you predict more of the same, you miss the Taiping Rebellion, the Boxer Rebellion, the Communist revolution, Deng and the liberalization starting in ‘79 (or some would say earlier), what's happened recently with the move toward greater autocracy…

China is one of the hardest countries to predict. You periodically get these very major sudden flips that most observers are not predicting. I'll just predict that China will stay hard to predict.

If you have riots or demonstrations in India, I’ll just say we’re going to get more of the same: we’ll still going to have riots and demonstrations, but India will be India. I’m not going to say that for China.

Jordan Schneider: As a sort of corollary to that, what’s the point of regional studies?

Tyler Cowen: You need smart, credible individuals in the State Department who have credentials, the ability to command facts intelligently, [and] the ability to be persuasive. If you’re done regional studies on China, are you in a better position to fill those jobs? I would say absolutely. It’s not just signalling — [though] some of it is signalling — but you’re actually better able to produce the kind of image and persuasiveness that the [State Department] job or working as a diplomat requires.

People who do regional studies do not only work for the State Department, but that’s just a very simple example that helps you see that it still can be quite useful.

Jordan Schneider: In the first few decades of the Cold War, the Ford and Carnegie Foundations basically created American area studies. I'm curious, Tyler, as you've been following this new wave of billionaires investing in progress studies stuff, what new intellectual outgrowths will come out of new philanthropic money in the coming years?

Tyler Cowen: I think donations will become less regular. The old model of donations is: you have a long-term relationship with a donor; they renew every year; it's quite predictable. I think younger donors think more in terms of venture capital hit-and-run: give something a boost to get it started and then hope it can find a way of supporting itself.

Be more non-traditional, take more chances, invest more in individuals, be more skeptical of universities and nonprofits… Those are all trends I see with tech money and crypto money. Now, how much more tech and crypto money will be generated? On tech, I'm pretty optimistic. Crypto money, I guess I'm less optimistic. That will depend, but I think those are some of the trends we’re already seeing in philanthropy.

As it relates to China, a lot of donors would like to do something, but they don't know what to do.

Say, somehow, you want to improve American relations with China. Well, what exactly do you do? It seems like there are a lot of ways you can spend a lot of money and just get marginal impact, like [making] a big donation to a regional studies program at a major university. It seems not very leveraged. People are looking for something to do and they're also afraid of becoming a target of China. We’ll see, but I’m not sure that area will change much.

Jordan Schneider: How would you spend money to prevent World War 3?

Tyler Cowen: I don't know that spending money is the way to do it. If I were the US government, what I would do is go to some of the countries that we're not so friendly with and boost the quality of their early warning systems, so they don't fire nuclear missiles thinking by mistake that they've been attacked — which indeed happened several times during the Cold War and we almost had exchanges of missiles. You want to give those evil state parties better information than they probably have now. This is all high levels of national security. It could even be [that] we're doing more of this than we let on. But it seems to me that's some low-hanging fruit that we could be doing more of. The thing I do is just talk more about the issue and try to raise consciousness.

Jordan Schneider: Recently, Blizzard Activision didn't renew its deal with NetEase, its Chinese domestic distributor. Shortly, millions of Chinese nationals who've been playing World of Warcraft their entire lives will no longer be able to. I'm curious: how important are shared cultural touchstones like video games, the NBA, and Marvel movies to keeping the peace?

Tyler Cowen: We had plenty such touchstones with Germany before WWI and WWII. It didn't matter, but it's certainly worth trying.

I had my own project to improve relations with China, which failed. I wrote a manuscript for a book, and my plan was to publish it only in China. It was a book designed to explain America to the Chinese and make it more explicable and understandable. I wrote the book [and] submitted it to Xinhua [Publishing House], which gave me a contract [and] even paid me in advance. But then a number of events came along, most specifically the Trump trade wars, and the book never came out. They’re still sitting on it, I don’t think it’ll ever come out. But that was my “misguided” project to do a very small amount to help the two countries get along better.

Jordan Schneider: Wow. What were your themes?

Tyler Cowen: If you think about Tocqueville, he wrote democracy in America so that Europeans would understand America better. So I thought, “If we're trying to explain America to Chinese people, it's a very different set of questions, especially in the 21st century.”

I covered a lot of basic differences across the economies and polities. Why are the economies different? Why is there so little state ownership in America? Why are so many parts of America so bad at infrastructure? Why do Americans save less? How is religion different in America (that was, I think, an especially sensitive topic)? Just trying to make sense of America for Chinese readers, but not defending it. [It’s] just some kind of olive branch of understanding: here’s how we are. I don’ think they’ll ever put the book out; of course, by now it’s out of date.

Jordan Schneider: But there are plenty of other countries on the planet who could use a little Civics 101.

Tyler Cowen: They could, [but] this is a book written for Chinese people with contrasts and data comparisons to China. To send the same book to Senegal would not really make sense.

Jordan Schneider: But if you publish it in the US, it will osmose out. I don’t think it needs to be published by Xinhua for Chinese people to read it.

Tyler Cowen: The book is out of date with facts. That's not a big problem: facts, you can update. But it's very out of date with respect to tone. Right now, everyone feels you need to be tough with China. You can't say nice things to China about China, or you're pandering. You look like LeBron James, or you're afraid to speak up. The book would've made a lot of sense in 2015, but its current tone doesn't make sense in the current environment. I still like the current tone, but it would be misread as something it's not.

Jordan Schneider: Well, I think it’s a more important book in 2023 than it was in 2015.

Tyler Cowen: It probably is. It will have some future; I’m still thinking about it and trying to get that right.

US Industrial Policy

Jordan Schneider: Industrial policy. Should the US be doing it, and if so, what are the institutional bodies or know-how that it would need to not waste everyone's money?

Tyler Cowen: People mean so many different things by those words. It’s better, I think, to be specific. I would say our industrial policy of the past has been: a) the military and b) strong governmental support for universities, rather than a lot of explicit, or even indicative, planning. I think that's worked pretty well overall. If someone says, “Well, there's a crisis in semiconductors,” or, “Doing things to help universities is far too indirect,” I strongly suspect that's true. I don't know exactly how to fix that problem. You have Intel laying staff off [and] not always stepping up to the plate in terms of delivery, efficiency and quality. So simply throwing money at it? I don't know.

I'm pretty convinced we shouldn't be doing nothing. I would just say it's more useful to talk about specifics. Industrial policy per se doesn't really mean anything to me.

Jordan Schneider: When I read about Boeing and the Northrop Grummans of the world and their dependence on US government contracts, it feels a lot like Chinese SOEs. How worried are you that more government money towards firms themselves and further away from labs and universities will lead to more firms losing their edge? Is that something that we should be concerned about, or are there certain industries where scale is so large that you’ve got to hold your nose and bite the bullet?

Tyler Cowen: I think we're stuck, at the moment. Often, the number of firms that can get through our military procurement process is no more than two. The process itself is so cumbersome and the companies you mentioned are pretty good at that, even if they're not always good at other things.

But it does seem to me our procurement cycle is broken. A lot of procurement can take 12 years or more, at a time when technology is changing so rapidly. In essence, [the government depends] on companies to do things outside the procurement cycle — as is happening with AI, I might add — and then [jump] on board very late and [commandeer] it in some fashion. Maybe that, too, is just what we're stuck with. It's just hard for me to believe that what we have now is the best of all feasible worlds. There must be a way to improve it. I'm not the person who has the knowledge to tell you how to do that, but my belief is that it has to be broken and wrong.

Tyler’s Dream Bureaucracy Jobs

Jordan Schneider: Tyler, what bureaucracies or organizations throughout history would you have most liked to work at or be a fly on the wall for?

Tyler Cowen: Something like the Aztec bureaucracy before Cortés arrived; I think I would learn a great deal. It wasn't a very pleasant bureaucracy, but it must have done a lot of things very well. [It’s] probably underrated from an efficiency point of view, like managing all those canals: were they all private? I'm not sure we know, but I doubt it. It's a lot of infrastructure in Tenochtitlan at the time; [there was] almost certainly a strong public role in that. Or the Roman Empire, or Ancient Greece.

Jordan Schneider: The Fifth Sun, which I think you recommended, was one of the most fascinating things I've ever read. It was [by] this anthropologist: the source material for the Aztecs is first-generation folks or people who are talking to the Spanish.

Tyler Cowen: They had codices. The libraries of the Aztec Triple Alliance were burned, so we're not sure what they had. But it was a truly remarkable civilization. When the Spanish arrived in what we now call Mexico City, they were impressed and astonished, especially by the network of canals. And if you look at what we now call biotechnology, they bred corn — a remarkable achievement. From what was a weed called teosinte that was very far from modern-day corn, they turned it into a food that drove numerous civilizations, including a lot of European civilizations. Untutored (in the formal sense) farmers in central Mexico playing around with plant breeding led to achievements that no other civilization has come close to, including ours as far as I can tell. An extraordinarily impressive set of people and culture; the language, Nahuatl, is beautiful; the poetry — what we know about them; the quality of the food… It all just seems incredible.

Jordan Schneider: You mentioned the Roman Empire.

Tyler Cowen: How good was it, really? How far did its reach extend? Someone writing another history book is not really going to teach me that, but if I could go back and work for the empire in AD150, I feel I'd come away with a pretty good sense of things. How long did it actually take to get a message to the other side of the empire? How were grain deliveries managed? How binding were the price controls? And so on. I'd learn all those things. How can you not want to do that?

Jordan Schneider: Let’s do the past millennium. Pick a few.

Tyler Cowen: Just current Singapore. I've gone to Singapore many times; I love my conversations with people who work in the Government of Singapore. I’m not a citizen, but to work there would be a great honor for me.

Jordan Schneider: How about a US bureaucracy?

Tyler Cowen: Well, something DARPA-like would be my pick. Maybe DARPA itself. As you probably know, the NIH is introducing its own version of a DARPA-like institution for healthcare. I know some people who are working with them, trying to make it better. I think those would be some areas where maybe I could have some positive input.

But if you put me somewhere like the Fed, even if you like my views, I don't really think I could contribute to what the Fed is doing. They have an excellent, numerous staff. I don't, per se, know anything those people don't. I think my marginal product at the Fed would be zero.

Jordan Schneider: What about [something that’s] less your marginal product and more “this would be really interesting, I get to learn a lot”?

Tyler Cowen: The two are related, right? What's interesting is to be able to improve or change something. So there are bureaucracies that are hopeless, that I wouldn't want to do. There are bureaucracies that are pretty good, like the Fed where my marginal product would be zero. Basically, a new institution or new branch of an institution is where I would want to be.

I gave a talk recently to ARIA in London. Of course, that's British, but that's their new science funding agency and they have [the] latitude to take a lot of chances. The people at Aria are all reading my book with Daniel Gross, Talent, and trying to think, “How can we use this book to shape who it is that we hire next?” I would be excited to be somewhere like that.

Jordan Schneider: Do you have some book recommendations about technology and bureaucracy?

Tyler Cowen: With books, it really depends [on] where you are starting from. I don't know any magic-quality book on technology and bureaucracy that is simply good for everyone.

I like the idea of reading in clusters. You could pick a bunch of books surrounding the mobilization of technology at the start of WII; that's a great cluster to read in. Or you could pick history of the National Science Foundation, or history of the Internet, or the Pentagon and information technology, and just read through the cluster. I think that's better than looking for the book.

Jordan Schneider: I've been searching for two years now for something as good as Men, Machines, and Modern Times.

Tyler Cowen: That's very good, but I think it comes down to reading in clusters. Books on technology maybe don't attract the very best writers; they attract people who love technology, which is fine. But there are really many wonderful biographies of literary figures that are captivating: Virginia Woolf, Samuel Johnson, Keynes (who, in a way, is a literary figure) … But when you get to technology, I don't see anything comparable.

Which fields have the best books?

Jordan Schneider: This is one of my questions: the lopsided ratios of book quality relative to topical importance. I don't want to say that a marginal Shakespeare analysis book isn't important, but where do you think there's overrepresentation or underrepresentation of great books?

Tyler Cowen: If you take Samuel Johnson, I believe there are three biographies of him that are just phenomenally good — a book you could just push on someone. Not someone totally uninterested, but you can just say, “This is a phenomenal book.” And there's three for one guy. That's great, but it's also a little screwy.

[With] most major tech figures, there's not one such book. And the people who could write great books on tech, like Patrick Collison, have a high opportunity cost. It probably won't ever happen. In literature people usually have very low opportunity costs, and they're rewarded for writing about literary figures.

So I think that's the pretty obvious division of where books turn out very well and where quality is under-provided: high opportunity costs, and technical subject matter that a bit repels what Mark Andreessen calls the “wordcels” — and that's most of tech.

Also, history of science is not the best area to read in. It's extremely important. There are plenty of books full of facts, but if you're looking for, say, a truly charming book on the history of botany or geology, I'm not saying there are none, but you have to actually look pretty hard. There are a few areas, like theoretical physics and Einstein's string theory, that [have] enough popular interest, [and] you have a lot of very good books by super smart people like Roger Penrose that are very appealing just to read. Evolutionary biology and Darwin: a lot of great books on that one thing which have sold very well.

There are these few areas that everyone goes crazy over, and then the rest of science, you know… I did some reading in the development of the science of taxonomy. [It’s] very important, actually: Linnaeus and so on, how we classify animals and plants… I'm not saying those are bad books, but there's not one I would push on you. There's no Richard Dawkins of taxonomy that I know of.

Jordan Schneider: What are the worst books for people to read at different points in their life? Have you seen latching onto a certain book ruin or spoil someone?

Tyler Cowen: I don't know. I'm very reluctant to make those judgements. I certainly know people who have read books and then become involved with cults, either formal cults or informally cult-like institutions. But maybe that was the best they could have done, and maybe they end up doing something useful. Look at Alan Greenspan: he was in the Rand Cult and he ended up running the Fed. Opinions differ on how good a job he did at the Fed, but you wouldn't say he just blew his mind on LSD and was a cult stoner. He was super successful. So it's very hard to know when the book is truly harming someone.

Maybe people should read more bad books and fewer good books; the contrarian in me is inclined to wonder if that isn't the case. I definitely wish people in tech would read more humanities.

Jordan Schneider: But didn’t someone say SBF is the great example of what happens when you get a tech founder who reads a lot of books?

Tyler Cowen: He posted that he hated books and didn't read them right. He said if you write a book, you're a fool. It should be a six-paragraph blog post.

You asked what areas have good books. I find very good books on China hard to come by. Almost impossible that it's one country where traveling in the country is of very high value compared to reading books about it.

Jordan Schneider: I think political science is a crime on humanity in terms of the quality of books that get written by people who could have been writing better books — or at least political science in so far as it's been done in the past 30 years. That's where I see the most missed potential: early-career folks who have done a lot of research but have to write painful things in order to get tenure.

Tyler Cowen: I agree there's far too much writing for tenure, but it's in most areas. It's not only political science. It's maybe more obvious in political science because you have a clearer, more vivid image of what the book should look like.

Charity

Jordan Schneider: How should normal people with four or five digits to spend think about giving away money?

Tyler Cowen: Give to GiveWell is one simple answer. They put a lot of serious effort and energy into figuring out which projects should get money. But it's not just about the rational side: you want to give to things where you will feel involved in a way that motivates your own altruism. It should have personal meaning for you. I don't think it should be a waste.

It's often a waste to just give to your alma mater, but the notion that you can sit down in a perfectly rationalistic manner [and] figure out the best donation, to me, seems a bit off.

You need to take your own imperfections into account and give to things that will remain vivid to you. I think giving to political parties usually is a waste. It's overrated. People do too much of it.

Audio Quality

Jordan Schneider: Tyler, what do you think about audio quality when listening to music?

Tyler Cowen: I have invested a great deal in audio quality, so I have a very expensive stereo sitting right next to me now. And I very much enjoy listening to the stereo really every day, [for] quite a bit of time. People who just listen on a computer or who listen with earbuds, to me, [are] aesthetically criminal.

Now, if you have a high-density file and the right kind of earbuds, the sound quality might be good. But it seems wrong to me that most music was not composed to be heard by ear, and you're injecting it into your brain in a way that is contrary to the intentions of the music makers. It's a very different kind of perceptual and emotional act.

I think you should listen to music in manners closer to how it was intended, and also go to live concerts. It seems to me with music listening, American society has become much worse over the last few decades.

Jordan Schneider: Have you tried IEMs?

Tyler Cowen: No.

Jordan Schneider: So these are wired headphones that, for a hundred bucks, can actually blow your mind in terms of quality.

Tyler Cowen: I have very good headphones. I don’t think they were IEMs, and the sound quality is good, but ultimately it’s not how I want to listen to music. It’s somehow taking music out of its proper context.

Jordan Schneider: Is there a skill you wish you had?

Tyler Cowen: Reading and speaking Chinese. That would be high on my list if China truly reopens. I prefer not speaking Russian, actually. Some of my family speaks Russian and I find it better not to understand all of it.

Very interesting, thank you for doing it! 💚 🥃

Jordan, what does “unless you’re a second or third standard deviation person” mean? Do you mean someone with a high IQ? I’m flummoxed…….