Viral Chinese Deepfake App Sparks Privacy Backlash

Also, How Huawei Avoided the Chinese Industrial Policy Kiss of Death

I’m Jordan Schneider, Beijing-based host of the ChinaEconTalk Podcast. In this newsletter I translate articles from Chinese media about tech, business, and political economy. If you were forwarded this email, feel free to…

Welcome to everyone who just joined via Mark Cuban’s LinkedIn post! We’ve now cracked 2000 subscribers.

Also, I’ll be doing the first ever live recording of ChinaEconTalk in DC at the Carnegie Endowment right off Dupont Circle on the 19th at 6pm. We’ll be discussing rare earths and 5G with Martijn Rassner from CNAS. Register here.

Zao is undoubtedly China’s breakout app of the summer. Capable of delivering convincing deepfake videos in mere seconds, Zao climbed to the top of app download charts and is now the talk of the Chinese internet. See below for a still of yours truly as the newest member of House Tarly.

A Brad Pitt one came out a little cleaner.

The reaction to Zao belies the view that Chinese consumers don’t care about their privacy. While I was willing to fork over a 3D scan of my face for your mild amusement, many Chinese were up in arms at Zao’s loose privacy policy and the broader security implications of democratizing deepfakes.

Zao’s rise also reflects the rising table stakes needed to impress users in 2019. While Instagram was able to go viral with filters mostly created by one person, Zao was built on the back of dating app MoMo’s success and likely cost tens of millions USD to launch. The “App Matrix” strategy, where tech firms don’t just focus on their flagship product but use revenues to crank out app after app in adjacent verticals, is now dominant in China. Further, increasing fixed development and ad traffic costs will only make it harder for those without major backing from established tech giants to compete.

The following piece by 36kr—translated in excerpts below—explores the commercial and privacy implications of such an app.

Zao’s day in the sun—See how quickly our privacy is disappearing

ZAO了一天,隐私的雷快爆了 August 31, 2019. Fan Ting and Shi Shengyuan.

Zao’s popularity shouldn’t come as a surprise. It has a lot of viral features: The content comes from popular movies and TV shows, and users who swap their own faces with those of the stars are getting a new way to express themselves. It allows users to mingle with friends and idols, and it includes good sharing and conversation functionalities.

What’s surprising is that there has been any backlash at all.

Chinese internet bigwigs have opined that Chinese users are willing to exchange privacy for convenience. But as Apple, Google, and Amazon have all acknowledged instances of listening in to users’ conversations, those who have been ignoring user privacy are—slowly but surely—recognizing its importance.

The team behind Zao

Zao is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Chinese dating app Momo.

As the internet market slowly shrinks, the strategy of creating an “App Matrix” is already the development strategy that most companies subscribe to, with Bytedance being the most successful.

AI face-swapping tech isn’t new; Pornhub and Reddit users [sites blocked domestically in China] have already come across it. What makes Zao special is that thanks to the company support, users don’t need to study how to render and train AI themselves. They just upload photos, wait ten seconds, and then share videos with their friends.

Behind this process is some high-end tech. Because of the glut of users, Zao servers were overloaded on the first day. AI experts have told 36kr that such hand-drawn filters cost at least a million RMB a pop, and Zao, which includes plenty of filters, makes for a really expensive product. [See here for a twitter thread in English on how Zao works, which relies less on AI and more on “tracking facial markers and applying 3D transforms” like this to match your face with the actor’s. My bet is that Zao spent a ton of money hand-rotoscoping the original videos.]

On August 30, a Weibo user named “ZAO Official Assistant” said: “I spent RMB 7 million [about $1 million] to rent a server. We’ve already spent a third of that in one night.”

Using AI to make consumer-facing products will undoubtedly be one of the future strategic directions explored by big firms, since only large companies can afford the cost of providing this sort of experience.

Zao has strong social features, which it is hoping will prevent it from just being another passing trend. It relies on QQ and WeChat to let users seamlessly import friends and contacts. What’s more, adding friends in the app allows you to make videos with their face and yours together. [Note: after this article was published, WeChat blocked the app for privacy as well as competitive reasons.]

Privacy issues

Today, with facial recognition starting to be used for electronic payment, one’s face is becoming more important than money or ID cards. Five years ago, people weren’t wary of uploading photos to the internet, but now, if you upload a photo without any filters or Photoshopping, anyone can take a chance at hacking your account. Alibaba’s Ant Financial has claimed that “at present it is impossible to crack facial-recognition payment through face-changing software on the internet”—which is somewhat reassuring.

In order to avoid the illegal repurposing of faces, Zao does not allow users to swap faces into their own uploaded videos; instead, it limits users to pre-selected movie and TV clips. Zao also promises that “[it] will use its best efforts to use the above content within a reasonable scope.”

But for internet companies—and in fact, almost all commercial organizations—the definition of “reasonable scope” will inevitably clash with users’ definitions. Before the company amended the user agreement, the privacy storm caused by Zao perhaps equaled the splash it made from people using it.

This week’s ChinaEconTalk podcast featured City University of Hong Kong Professor Doug Fuller diving deep into Chinese tech industrial policy.

One topic we touched on is just how much an outlier Huawei is in the chinese tech space. Ren Zhengfei has really accomplished something remarkable in investing in cutting edge tech when nearly all other Chinese firms succumbed to the warm embrace of cushy government contracts instead of fighting it out overseas.

“[Huawei CEO and founder] Ren Zhengfei — there was a method to his madness. He decided to forgo what were these rational incentive structures to just embrace state procurement and instead took a very high risk strategy of very early on looking abroad for contracts, for markets because he really wanted to hone Huawei’s capabilities by competing against the best…

In contrast, a firm like ZTE was more than happy to be much more reliant on the Chinese marketplace when it went abroad. It sort of very much followed this [path of taking] China Development Bank subsidized loans to sell equipment in African countries where the leading foreign firms were not interested because the price points were so low.”

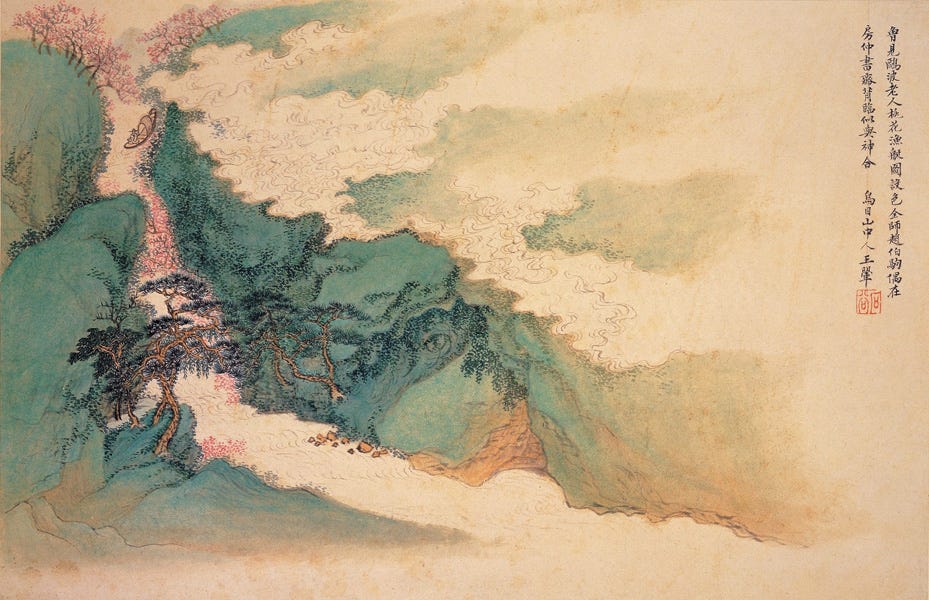

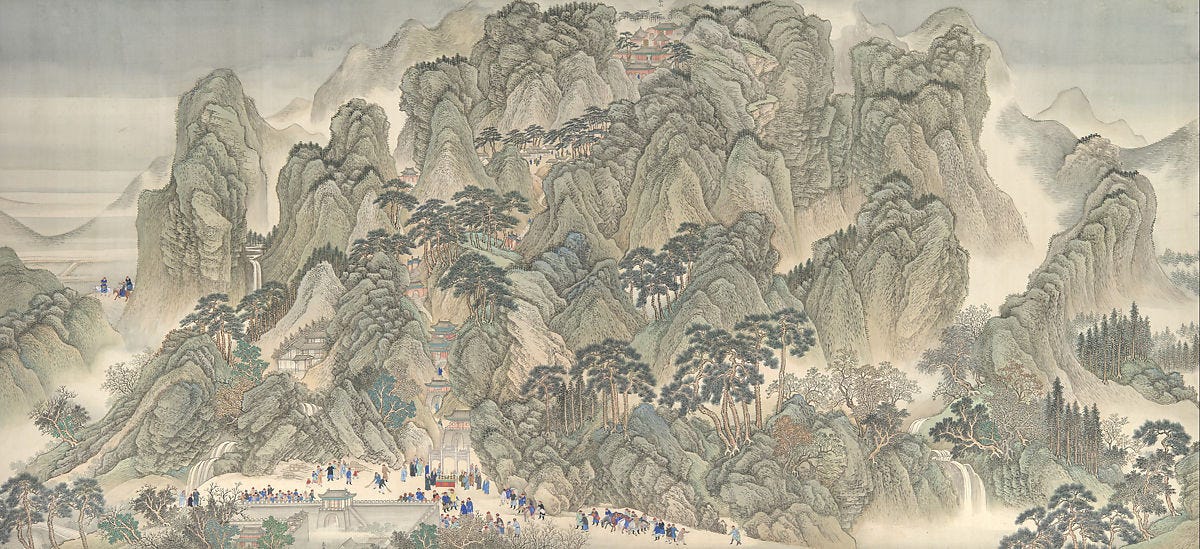

Chinese Landscape Painter of the Week: Wang Hui

Wang Hui, from the early Qing Dynasty, didn’t directly observe nature but rather sought to build off and interpolate past masters. As Maxwell Hearn writes, while Wang was initially dismissed as little more than an antiquarian, in fact “Wang’s paintings combine disparate stylistic influences in totally new and inspired ways to make each ‘performance’ spontaneous and fresh. Wang did not merely imitate the past, he reinvented it.”

Unlike BaDaShanRen, the painter we recently profiled who after the fall of the Ming literally refused to speak, Wang Hui had no problem cozying up to the new Manchu rulers. He painted giant scrolls memorializing the Kangxi Emperor’s two southern trips, and was ultimately rewarded by Kangxi giving his paintings the description of “clear and radiant.” Here’s a really cool youtube lecture on him.