Where’s China’s AI Safety Institute?

AI Safety Institutes from Kenya to Singapore are networking in San Francisco this week. What about China?

Karson Elmgren and Oliver Guest are researchers focused on international AI governance and China. Their full report on Chinese AISI counterparts is available here.

AI Safety Institutes, or AISIs, are one of the most important new structures to emerge in international AI policy over the last year. The US and UK were the first to establish AISIs in October 2023, followed later by the EU, Japan, Singapore, France, and Canada.

This week, San Francisco is hosting the first conference of the International Network of AI Safety Institutes. The AISIs have thus far signed various bilateral cooperation agreements, but the San Francisco conference will be the first multilateral discussion forum knitting all AISIs together.

However, one country is conspicuously absent from the AISI club: China.

To date, China has not designated an official, national-level AISI, despite its prominent position in AI and apparent ambitions to influence international governance. Nevertheless, as our recent report highlights, there are a number of government-linked Chinese institutions doing analogous work. Looking forward, it still seems plausible that China will establish a single body acting as an official counterpart to AISIs around the globe.

What are AI Safety Institutes?

In general, AI Safety Institutes are government-backed technical institutions that focus on the safety of advanced AI.

There’s a lot of variation between such organizations — some focus on research while others focus on recommending guidelines, and, naturally, some AISIs are much more well-funded than others.

This variation makes it difficult to pinpoint exactly what it means to be an AISI. The EU AI Office, for example, has regulatory functions and almost no focus on research — which makes it unlike any other AISI. Yet in practice, it has played the role of an AISI by representing the EU in AISI-specific convenings.

Conducting AI safety evaluations has been a key focus for several AISIs. They are also contributing to safety evaluation as a field by developing and releasing software tooling for the evaluation of AI systems.

More broadly, many AISIs are interested in technical AI safety R&D, standard-setting, and international coordination. To achieve these functions, the official AISIs serve as an anchor for a wide network of government and civil society participants.

Is China even interested in having an AISI?

Despite frequently calling for the United Nations to serve as the key platform for international AI governance, China has thus far revealed a clear preference for maintaining a seat at the table of Western-led minilateral efforts.

Beijing sent a delegation (led by Ministry of Science & Technology Vice Minister Wu Zhaohui 吴朝晖) to attend the UK AI Safety Summit in Bletchley Park. This was the first time AI-induced catastrophic risks received international attention, and it was during this summit that the US and UK announced the creation of the earliest AISIs. Chinese representatives also attended the follow-up event in Seoul — but they did not sign the joint statement for countries in attendance, which declared a “shared ambition to develop an international network among key partners to accelerate the advancement of the science of AI safety.”

But hesitation hasn’t stopped prominent Chinese AI scientists and policy experts from actively seeking dialogue with international counterparts. At a conference in July 2024, Andrew Yao 姚期智 and Zhang Ya-Qin 张亚勤 even publicly advocated for China to establish its own AISI to participate in the growing network.

(For context, Andrew Yao is the Dean of Tsinghua University’s Institute for Interdisciplinary Information Sciences and arguably China’s most highly respected computer scientist. Zhang Ya-Qin is the former President of Baidu and the dean of the Tsinghua Institute for AI Industry Research).

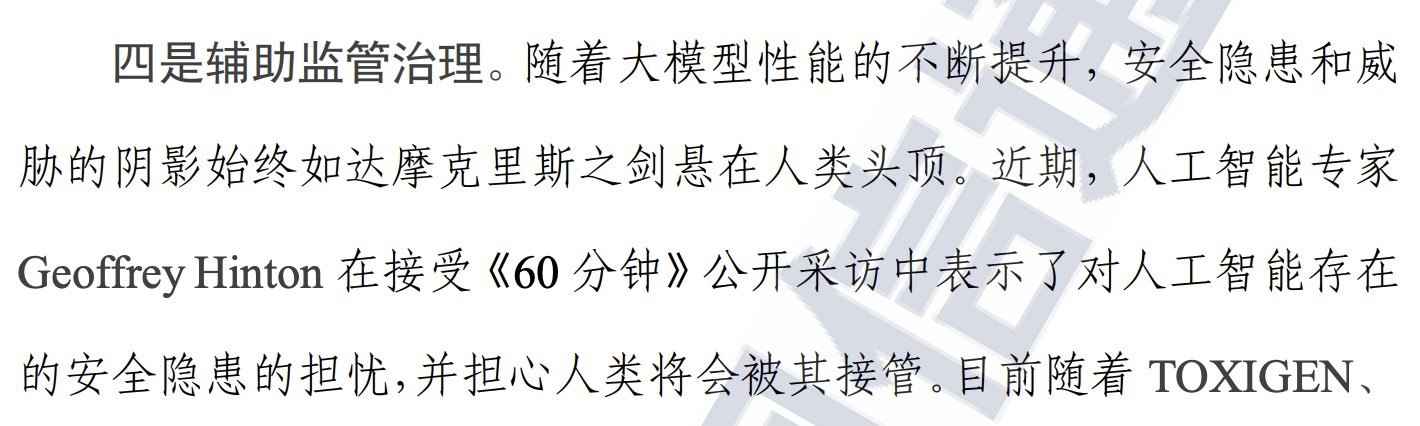

There have even been some signs that some Chinese officials are similarly concerned about catastrophic risks from AI. Most tellingly, the recent Third Plenum decision included a call to establish “oversight systems” for AI safety in a section focused on large-scale public safety threats like natural disasters. A June 2024 report by the quasi-governmental China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) referred to AI as a “sword of Damocles,” and cited Nobel laureate Geoffrey Hinton’s concerns about AI “takeover” to explain the need for an AI evaluation regime.

Why the hesitation?

Even if there is an appetite for a Chinese AISI, there are a few obstacles standing in the way.

One significant barrier is internecine jockeying over who gets to call the shots on AI safety. Beijing and Shanghai have each recently established local AISI-like bodies, which are already not-so-subtly vying for a promotion to the national level. The newly-established Beijing Institute of AI Safety and Governance hosted the UK AISI for a meeting in October 2024, and even abbreviated its name as “Beijing-AISI.”

Similar maneuvering may be happening within the Chinese party-state system over the location of AISI facilities, the personnel involved, and the goals of a potential Chinese AISI. The variation between existing AISIs could make this jockeying particularly intense, as there is no definite playbook for a Chinese AISI to follow.

There’s also the question of optics. Given China’s own leadership ambitions in AI governance, it’s presumably not the best look to follow a trend established and led by the US and UK. Though the AISI network incorporates non-western countries like Singapore and Kenya, it’s sometimes perceived as an Anglo invention — to the extent that Japan’s AISI is named in English — the body’s official title is AIセーフティ・インスティテュート , AI Sēfuti Insutityūto. (The logo, too, is suspiciously similar to that of UK AISI.)

Finally, even if China wanted to participate in the AISI network, there’s some uncertainty about whether they would be welcome. It would be embarrassing to establish an AI Safety Institute, on a Western-created model, in order to join a Western-led club — only to be passed over for an invite to the party. If Beijing believes that the UK or — more likely — the US could block them out from the AISI network, that reduces the incentive to create an AISI in the first place, with an additional disincentive for China’s self-esteem.

The fact that China did not sign the Seoul declaration that launched the network would not necessarily be a barrier to their joining. Kenya was not a signatory but has been invited to the first convening of the AISI network. Incidentally, signatories Germany and Italy will not be attending, and will only be represented by the EU delegation as a whole.

If China is to set up an AISI, it would likely need to balance the interests of various influential stakeholders domestically, appear distinct enough to constitute a uniquely Chinese contribution to international AI governance, and be viewed by leaders in Beijing as burnishing China’s prestige on the global stage.

If not an AISI, what Chinese institutions play AISI-like roles?

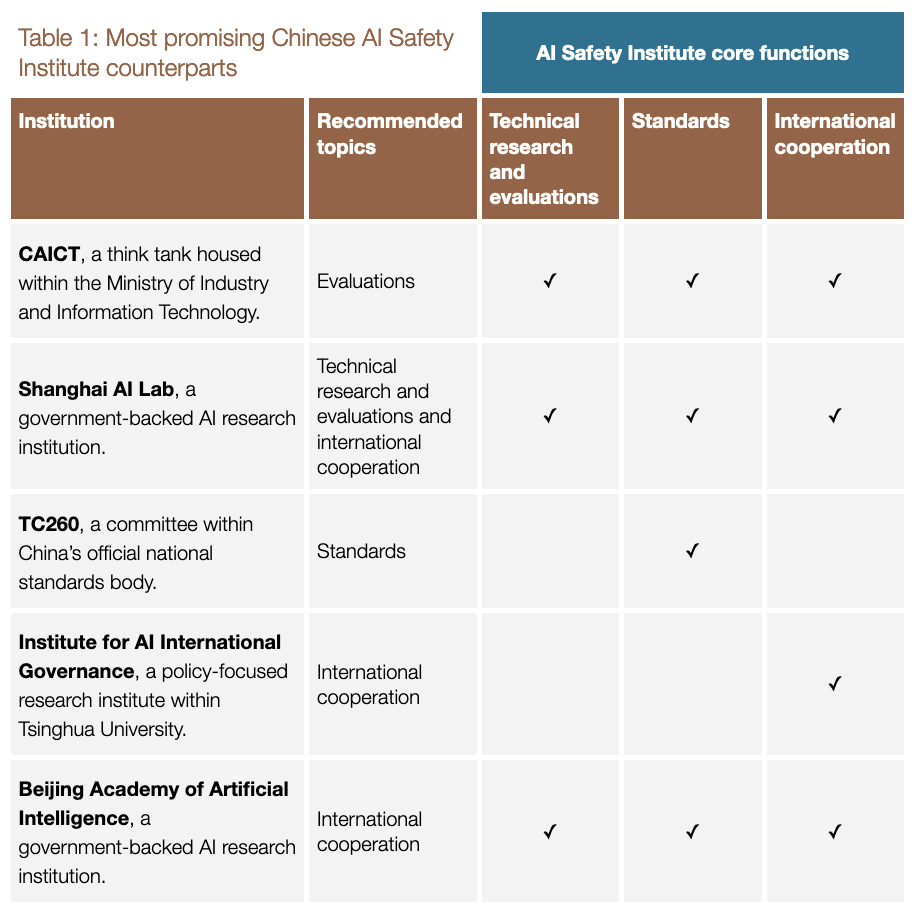

Even without an AISI, several institutions in China perform AISI-like functions. If China eventually sets up an AISI, it would likely draw on these existing bodies doing related work, either by stitching together a consortium or drawing on them for personnel and intellectual influence.

However, AI safety is an emerging, dynamic environment — one where a new organization could suddenly rise to prominence at the national level. Additionally, some of China’s AISI-like organizations are influential but much less suited to international engagement. This includes China’s online censorship office, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). Apart from ensuring that internet content conforms to CCP ideology, CAC also plays a key role in regulating AI in China. CAC authored rules on algorithmic recommendation systems and “deep synthesis” systems (deepfakes, essentially), and it administers the algorithm registry that functions as a quasi-licensing regime.

Does it really matter if China doesn’t have an AISI?

AISIs were created for a reason. The lack of a Chinese AISI makes international engagement more difficult in several ways:

International counterparts will have to decide for themselves which organizations in China are most relevant and authoritative. Engaging with multiple institutions of questionable influence might come at the expense of cultivating deeper working relationships with the most important Chinese partners.

International engagement is underpinned by domestic stakeholder management, which is done most effectively by a single entity with an official mandate.

A centralized hub of AI safety expertise would presumably come with a standard operating procedure for involving the higher-ups in the CCP, facilitating smoother and faster decision-making on strategic questions.

That said, China’s absence won’t render international AI cooperation dead on arrival. Participation in international governance — and maybe even the international AISI network — doesn’t necessarily require China to have an AISI. Neither Kenya nor Australia have established an AISI as of November 2024, and yet both were invited to San Francisco. And, although China wasn’t invited to the San Francisco meeting, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said in September that officials were “still trying to figure out exactly who might come in terms of scientists,” implying that some individual Chinese scientists might be involved.

But, even if China did have an AISI, this wouldn’t guarantee the willingness of other countries to cooperate. Washington generally has a frosty attitude towards engagement with China these days, which might get even frostier with the incoming Trump administration. The perception that the US and China are competing in an “AI race” might make engaging in AI safety dialogues particularly difficult.

On one hand, some US government officials reportedly opposed China’s inclusion at the Bletchley Summit. On the other hand, government representatives from China and the USA did meet in May 2024 for a dialogue about “AI risk and safety,” and the two sides even agreed to a subsequent follow-up. The White House statement about the dialogue notes that US representatives raised concerns about Chinese misuse of AI, which aligns with Biden’s AI executive order. But publicly available evidence doesn’t actually specify which government initially requested this meeting — and thus it’s anyone’s guess if this dialogue will continue into the next administration.

In the meantime, international partners can choose from a constellation of Chinese organizations doing AISI-analogous work. For example, if the US or UK AISI wanted to discuss ways to measure whether new AI models can enable non-experts to create and deploy bioweapons, representatives from CAICT or SHLAB could convey relatively authoritative information about AI safety evaluations in China. Similarly, our report finds that Technical Committee 260 is the clear frontrunner for international partners looking to discuss China’s standard-setting legalities.

On these narrow topics at least, engaging with these institutions could provide many of the same benefits as engaging with an officially designated AISI.

Addendum — Who would run a Chinese AISI? / Surprise guests in San Francisco?

If we were to speculate about who would lead a Chinese AISI, the aforementioned Andrew Yao would be a natural choice. Yao is a computer scientist born in Shanghai, raised in Taiwan, and educated in the US. He returned to China (taking PRC citizenship) later in his career, and won the Turing Award for his work in the theory of computation. He has received a public letter of laudatory recognition from no less than Xi Jinping himself. At Tsinghua, he leads the Institute for Interdisciplinary Information Sciences which houses the famous “Yao Class,” widely recognized as one of China’s top undergraduate STEM programs. For a number of years, Yao has been very active in discussing AI safety as a technical priority to Chinese audiences, and a pillar of international scientific dialogue on the topic.

Other grandees who might be involved include the respected heads of three key state-backed AI research groups — Huang Tiejun 黄铁军 (Chairman of BAAI), Gao Wen 高文(Director of Peng Cheng Lab), or Zhou Bowen 周伯文 (Director of SHLAB).

Huang has written about risks from advanced AI for many years, including co-authoring a 2021 paper entitled “Technical Countermeasures for Security Risks of Artificial General Intelligence.” He has also recently discussed his expectations for the trajectory of advanced AI development, predicting that when AI’s cognition and perception capabilities surpass human levels, “physical control” will be “impossible.”

Gao Wen was also a co-author of the 2021 Technical Countermeasures paper, and has recently referred back to the threefold method of risk analysis outlined in this paper, including related to the lack of interpretability and the difficulty of control. However, PCL’s close links to the Chinese military, as a main “cyber range,” could potentially make Gao’s involvement awkward for international engagement.

Zhou Bowen, though evidently newer to the topic, has recently been promoting the idea of an “AI 45° Law,” according to which AI safety should keep pace with AI capabilities.

A more mid-career technical expert who would be well-positioned to be tapped by a Chinese AISI is Yang Yaodong 杨耀东, a professor at Peking University who leads the PKU Alignment and Interaction Research Lab (PAIR). In China, PAIR is one of the key research labs working on methods to align AI systems with human values under human control.

Finally, there are two leaders in Chinese AI governance with a valuable track record of international engagement. They are Xue Lan 薛澜, Dean of the Tsinghua Institute for International AI Governance, and Zeng Yi曾毅, Professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Automation and head of several other research and policy organizations. Both have been signatories to multiple statements in the International Dialogue on AI Safety series. As of mid-2024, Zeng also leads the Beijing Institute for AI Safety and Governance — the organization mentioned above as positioning itself to serve an AISI-like function. (The aforementioned Yang Yaodong also appeared on a slide at Beijing-AISI’s announcement ceremony listed as one of the organization’s “core research forces.”)

Check out Karson and Oliver’s full report on Chinese AISI counterparts here.

It already exist https://aisi-cn.org.cn/