Why are Chinese semiconductor stocks skyrocketing?

Nikkei just put out a strong long-form piece on China’s semiconductor push. It details the wildly above-market salaries and billions of dollars available in investment currently luring American and Taiwanese engineers to move to the mainland. The fact that the Yangtze Memory, China’s only NAND flash memory chip producer, got permission to shuttle workers in and out of its Wuhan fabs during the height of the virus goes to show just how much the government sees domestic fabrication as a national imperative.

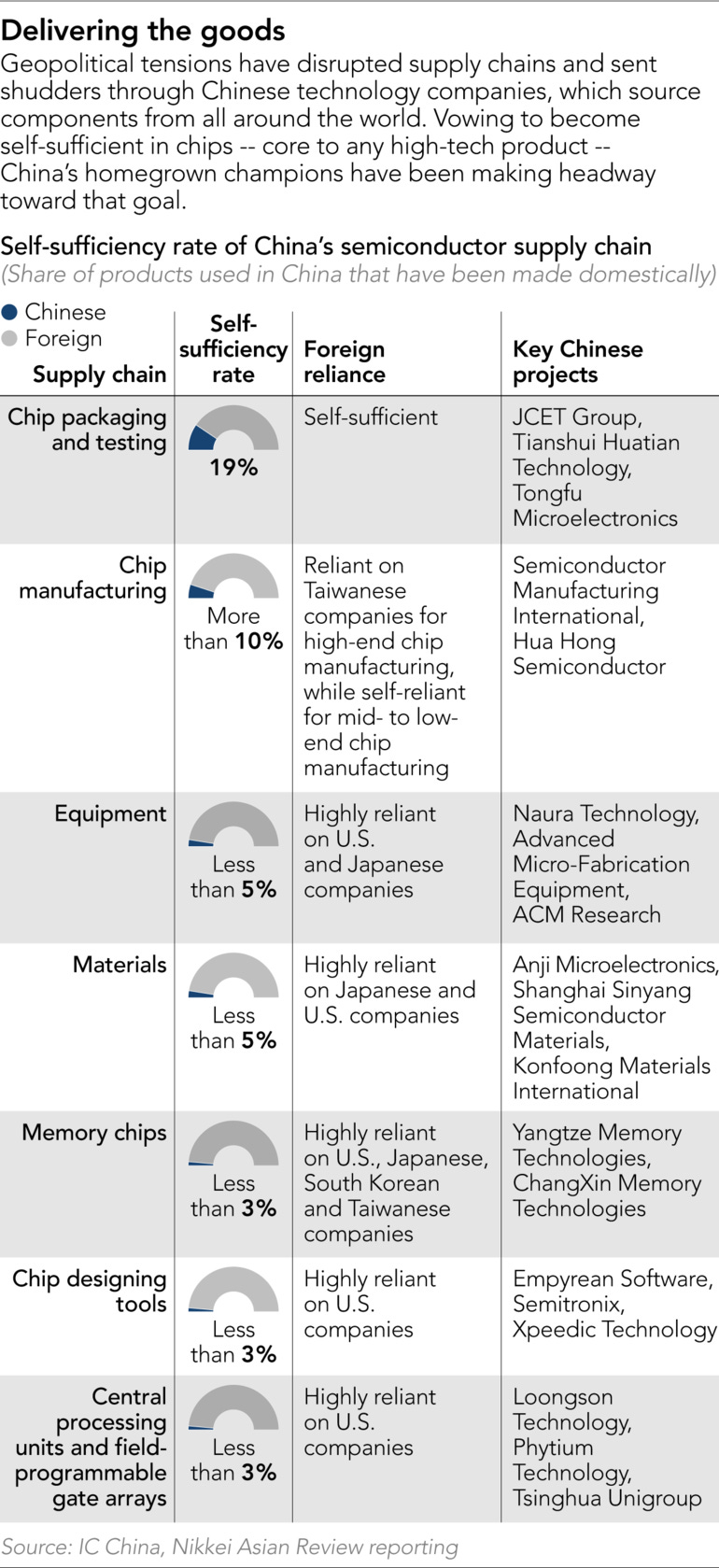

That said, China still has a long way to go before reaching a point where its technology firms can produce globally competitive projects without incorporating foreign components. As Nikkei writes,

Although its technology is still at least one generation behind its international competitors, Yangtze Memory has just begun to produce China's first homemade 64-layer 3D NAND flash memory chips. Chinese companies such as Huawei and Lenovo are among the first wave of buyers. NAND flash memory chips are vital storage components used in electronic devices from smartphones, tablets, PCs, servers and data centers. The layered-3D stack production technology is patented and controlled by foreign players, but Yangtze Memory says it has developed its own stacking structure for building such chips.

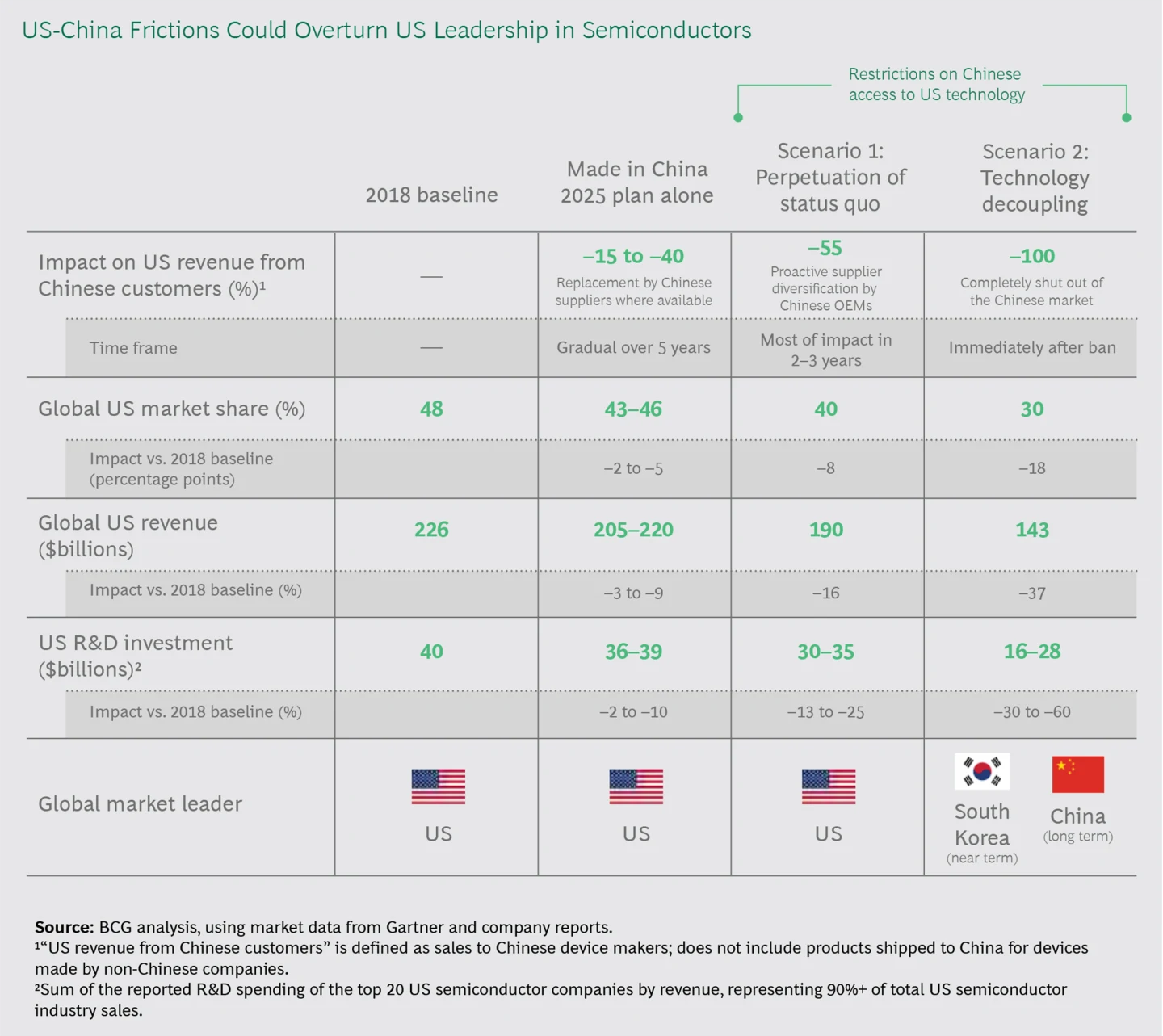

Recently SIA (the lobbying body representing America’s semiconductor industry) got BCG to write them a report detailing the impact of restrictions on Chinese access to US technology on American firms’ global standing. They argue that “Continuation of the bilateral conflict could jeopardize US semiconductor companies’ ability to conduct business in China on an equal footing with their competitors, both Chinese and from other regions. That could pose a direct risk to the estimated $49 billion of revenue (22% of its total revenue) that the US semiconductor industry derived from Chinese device manufacturers.” The resulting cuts to R&D could, in turn, make it easier for foreign firms to press ahead of their American rivals. Their money slide:

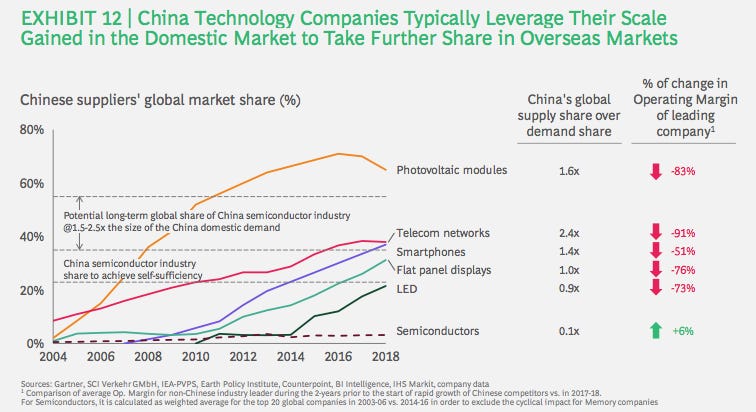

BCG posits that if Chinese companies can ramp up quality production, US semiconductors could suffer a fate similar to US telecom equipment manufacturers.

In 2000, three North American companies—Lucent, Nortel, and Motorola—were global leaders, with approximately $100 billion in total combined revenues. After demand dried up during the tech downturn that followed the bursting of the dot-com bubble, networking equipment companies’ revenues plunged. By 2005 the combined revenues of the three companies had fallen by 45%. As a result, they were forced to restructure their businesses and slash costs, including R&D. Although they kept investing the same 12% of their revenues as in the pre-crisis years, their annual combined R&D spending dropped from $12 billion to $6.7 billion, a 45% reduction in just five years.

This impaired their ability to maintain their technological lead over their European competitors and to support new product development in the evolving wireless equipment market, just as carriers across the world were rolling out wireless networks based on new technology standards. At around the same time, Chinese manufacturers that had entered the market in the mid-1990s began to introduce “good enough” networking equipment at much lower prices. The Chinese contenders rapidly expanded at home and in emerging markets, and by 2008 had captured around 20% of the global market. Over the ensuing decade, the share of Chinese telecom network equipment companies has nearly doubled, to 38%. Meanwhile, the three former North American giants ended up being acquired by their European competitors for a fraction of their former valuation[s]. Today, there are no US-based suppliers of radio-access network infrastructure, which is critical for the rollout and management of the 5G networks underlying the next wave of applications that will transform the global economy as they usher in everything from massive IoT applications to autonomous vehicles.

If any readers would like to challenge or add to that comparison, I’d be happy to run their comments.

The consultants’ analysis, however, falls for the fallacy of taking Chinese policy aspirations as foregone conclusions. It does not answer the central question of whether Chinese firms will be able to hit the Made in 2025 goals to saturate domestic demand and ultimately surpass American technological prowess in the space. As Dan Wang has written, the Chinese tech firms that make headlines in the west rely heavily on recommendation algorithms, games, business model innovations, and legions of low-paid workers. Generating the likes of Bytedance and Meituan, while impressive, does not inevitably lead to cracking the toughest industrial nuts like aerospace and semiconductors.

Dan argues that in the long term, since Chinese producers make most of the world’s stuff, they’ll end up learning by doing faster than their overseas competitors. But the political economy distortions brought on by so much government interference in an R&D-intensive ‘strategic industry’ may end up hampering the rise of world-beating firms. Perhaps China has yet to repeat the global market share gains in semiconductors that it achieved in photovoltaics and LEDs because the most difficult tech requires something beyond China’s industrial policy playbook.

I would, however, recommend the BCG paper for its appendix that lays out a nice model of how the entire semiconductor industry ticks.

How will coronavirus impact the US-China chip race going forward? My hot take is that this doesn’t necessarily reshape the political dynamics. Even if a coronavirus-driven recession that causes Trump to rethink some of his tariffs, I don’t see him or Biden backing down from export controls. Perhaps to reshape the dynamics BCG lays out, the US government could begin to more actively subsidizing investment, though unless some of this gets snuck into the upcoming stimulus bill I’d be very surprised to see the dollar amount approach the $12 billion in lost R&D funding BCG predicts in its downside scenario.

Stay tuned for more on this next week as I walk through Jon Verwey of the International Trade Commission’s 2019 deep dive into China’s semiconductor industrial policy missteps.

Stick around till the end of the email for China Twitter Tweets of the Week. I’m also open for business if anyone has research projects or consulting gigs!

This week’s translation is a recent article by AI Finance which dives into the surprising surge of Chinese semiconductor stocks in late Feb and early March. It focuses in particular on how localization efforts sparked by US tech sanctions have raised hopes for domestic manufacturers. It’s worth noting that since this article’s publication, many of these stocks are 20% or more off of their recent highs. If you’re enjoying the volatility of the past two weeks, you’ll have a blast in China.

Why are chip stocks skyrocketing?

Original Chinese here. March 4, 2020. Authors: Tang Yu, Zheng Ya Yong.

In 2019, semiconductor stockers were all the rage. Not only Zhou Shengwei but three other companies, Huiding Technology, Weir Shares, and Wingtech have all been promoted to the "100 billion market value club" ($14b). Going into 2020, four more firms (Zhaoyi Innovation, Lanqi Technology, Sanan Optoelectronics and China Micro) all also passed this threshold.

In response to such a surge, many people in the semiconductor industry spoke bluntly to AI Finance. One who had been in the industry for many years admits, "I didn't buy any chip stocks because the more familiar I got with them, the more I dared not buy them." Another person joked, "first people speculated with caterpillar fungus and Pu'er Tea. Now it's chip stocks!"

Even the owners of these companies are now apprehensive, as they had no idea their firms could possibly be worth so much. Among the 77 semiconductor companies in the A-share market, 80% have a P/E ratio over 60, and 20 have a P/E ratio exceeding 200.

So what's going on?

During the coronavirus epidemic, money has nowhere to go. Real estate and transportation infrastructure are no-gos. The tech stocks on the A-shares market are led by chips. Further, with the US creating more and more export bans on technology, domestic substitution is growing more common, which helps chip stock investors dream of a bright future. Said one industry source, "the US restrictions are sort of acting like a spring. The more they squeeze, the more our stocks rebound."

Said one investor, in the past, large domestic consumers were only willing to use European and American products. Semiconductor startups found it very difficult to raise capital and had very low valuations. But now, given the new threat to the supply chain, these buyers are focusing more on localization.

In addition, big firms like Huawei are changing their mind. For example, in 2019, Huawei set up a plan to invest 100 million yuan into small and medium-sized domestic enterprises, hoping to help spark a domestic ecosystem.

Fang Jing, chief analyst at Cinda Securities, said that "independent and secure are the main investment theses running in the market." 自主可控是贯穿未来10年以上的投资主线

One experienced observer who has been engaged for years in the integrated circuit industry understands the popularity of certain stocks. For instance, Zhaoyi Innovation's 200+ P/E ratio is because its business is designing memory chips, and China domestically lacks such abilities. "Most of what we use now is foreign, so this is a major opportunity. For the country, this is a fundamental product, so there's a high potential for domestic substitution." Although there is still a gap between domestic and international flash memory, it's closing.

China is an important country in the global supply chain. With China every year consuming one-third of the world's semiconductor products, it's not too surprising that semiconductor companies with a market value of two or even three billion yuan will appear in the near future.

In 2019, two fires ignited the chip industry: the Huawei incident in May, and the opening of a new science and technology innovation board [on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, created to help Chinese tech firms IPO domestically]. Some stocks on their IPO days [on that board] rose by 400 or even 500 percent.

One anonymous investor believes that soon, the investment boom will dramatically increase capacity, leading to severe competition on the price of the sort that hit the photovoltaic industry.

And what about in the nearer term, what's the impact of coronavirus?

Because chip manufacturing plants can't stop their machines [without doing severe damage to the equipment], and since chip manufacturing isn't all that labor-intensive, the production hasn't dropped off dramatically.

When it comes to chip design companies, AI Finance has learned that some emergency products have been resumed first. Dai Zhongwei, general manager of Guanxin Electronics, spoke to AI Finance, saying that designs for new products may be slightly delayed. However, "in fact, it's not so urgent. Most chips, like Huawei Hisilicon's, have small iterations from generation to generation, and many products are universal. If you're three and a half months late, it's not that big a deal."

Labor-intensive packaging plants have suffered the most significant impact.

On the whole, second-order effects may hit the semiconductor market until later. Demand is likely to contract, and a drop in the production of supplies from Japan (which has a market share of over 60% in many semiconductor material segments) could constrict the entire industry.

China Twitter Tweets of the Week

Real talk though that book is a 6/10 at best. If you want some meaty world history check out Ian Darwin’s After Tamerlane.

Thanks so much for getting this far!