Why China Stopped Liberalizing

From Deng to the Death of Xi. Plus: can engagement with authoritarian states ever work?

Welcome back to part 3 of our interview with Yasheng Huang 黄亚生, the author of The Rise and Fall of the EAST: How Exams, Autocracy, Stability, and Technology Brought China Success and Why They Might Lead to Its Decline.

In this final installment, we discuss…

The steelman case for why China needed a Xi,

What sets Xi apart from his predecessors,

Succession challenges and the importance of term limits in authoritarian states,

Why engagement with China failed to produce political liberalization,

How the US could have better leveraged economic relations with China,

Creative approaches to human rights advocacy in China.

Co-hosting today is Ilari Mäkelä of the On Humans podcast. Here’s our first interview if you missed it, and here’s the first half of the second installment.

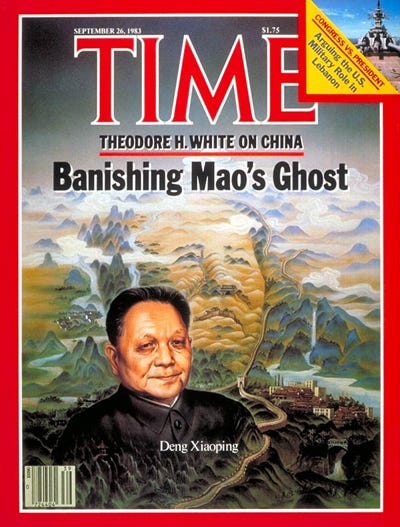

Succession Crises and The Death of Deng’s Legacy

Ilari Mäkelä: Let’s examine China today then. In some ways, Xi Jinping seems like a natural progression from Hu Jintao, who made China more statist, with Xi taking it even further. However, one could argue that this represents a more dramatic shift, to the extent that China today is no longer in the reform era but has entered a completely new phase. How abrupt was this change? In what sense was it new rather than just an intensification of previous trends? Where are we now?

Yasheng Huang: Looking at the three leadership generations — 1989, 2002, and 2012 — we can analyze them as such:

The 1989 generation changed the rules of the game, essentially reversing the political reforms initiated by Zhao Ziyang.

The 2002 generation, led by Hu Jintao, changed the game but not the rules of the game. Within the existing structure, they strengthened government control and cracked down on social media, (that began under Hu Jintao, by the way, not under Xi Jinping). They also went quite far in controlling NGOs due to concerns about a potential Velvet Revolution.

Xi Jinping changed the rules of the game again, this time reversing Deng Xiaoping’s reforms. This represents a more significant change compared to the 1989 generation’s rule changes or the 2002 generation’s game changes. In modern Chinese politics, one doesn’t typically challenge Deng Xiaoping’s legacy.

Ilari Mäkelä: I agree. Could you be more specific about how Xi Jinping overturned Deng Xiaoping’s rules?

Yasheng Huang: Xi Jinping has made several significant departures from the Deng Xiaoping era. These include eliminating term limits, removing mandatory retirement, shifting away from economic growth as the Chinese Communist Party’s primary objective, and moving away from cooperation with the West in foreign policy.

These are substantial changes. The 1989 generation altered Zhao Ziyang’s implementations of power separation between party and state, transparency reforms, and media protections.

However, they didn’t touch the core principles established by Deng Xiaoping, such as term limits and mandatory retirement. Both Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao stepped down after their terms ended.

To challenge what I call the “third rail” of Chinese politics required something extraordinary. While the direction was the same, the departure was more abrupt and sharper. It was directionally consistent but represented a more significant shift.

Ilari Mäkelä: How positive or negative is this change? There’s an easy way to view it negatively as more autocratic. However, let me present a case for Xi’s era after 1989:

The Shanghai model of development led to crony capitalism and massive corruption.

The rural-urban gap resulted in significant economic inequality.

The purely GDP-driven model of legitimacy led to environmental degradation.

Xi came to power promising to tackle corruption and later focused on rural poverty. Branko Milanović, an inequality expert I recently interviewed, convinced me that there’s been a noticeable rise in the bottom 20% of global incomes, primarily due to China’s poor becoming richer over the past decade.

Additionally, Xi is more focused on issues like clean energy. During my time in China, I conducted a small field project on a ten-year fishing ban implemented by the government on the Yangtze River — something unlikely to have occurred a decade earlier.

That’s my case for the need for a Xi Jinping-like figure. What’s your response?

Yasheng Huang: Milanović is correct that inequality declined under Xi Jinping, and the bottom 20% saw improved income growth relative to GDP growth. In the revised version of my 2008 book, I present statistics supporting this claim. However, the question remains — does achieving these goals necessitate eliminating term limits and mandatory age retirement? Does it require such a high degree of centralization?

It may require some revision of the economic growth objective, moving away from blind pursuit of GDP growth numbers in favor of income growth for poor and rural people. I agree with that. But consider two scenarios and choose between them:

1. Achieving these goals with higher GDP growth

2. Achieving these goals with lower GDP growth

Any rational person would choose the scenario where both higher income growth for rural Chinese and higher GDP growth for the country are accomplished. This was China in the 1980s, where each increment of GDP growth significantly improved rural income. The 1980s outperformed the subsequent three generations by a wide margin.

Xi Jinping did improve upon the previous two generations of leadership, but it’s important to note that under Jiang Zemin, income improvement substantially slowed.

Xi improved from a low base, which is commendable, but it was achieved largely through transfers from urban to rural people, not through fiscal stimulus.

This transfer approach can work for a period, but with the current challenges to GDP growth, it will become increasingly difficult to rely on pure transfers. During Zhao Ziyang’s era, extensive transfers weren’t necessary because rural income was growing rapidly on its own.

I would argue that tackling corruption and environmental issues doesn’t necessarily require political centralization. There are other ways to address these problems. The fact that they’ve been fighting corruption for eleven years suggests either that there’s too much to work on, or that their methods are ineffective.

Perhaps it’s time to rethink this approach to tackling corruption.

I would argue that transparency, government disclosure, increased media scrutiny, and more legislative oversight could be more effective in combating corruption than the current purge approach.

Ilari Mäkelä: Essentially, they’re doing the opposite of what you would recommend. Is that correct?

Yasheng Huang: In terms of methods, yes. I support the objectives of environmental improvement, government cleanliness, and improving the bottom 20% of incomes. I also agree that everything shouldn’t revolve around GDP growth. However, I disagree with their methods.

Regarding GDP growth, a cleaner approach could be adopted rather than the current investment-heavy method. This would involve allowing small-scale entrepreneurship, low-tech ventures, and more service sector activities. Unfortunately, these are not the activities encouraged by the current government.

Ilari Mäkelä: To summarize the historical development from the early reform era until today — you have the liberalization in the 1980s, followed by a period of confusion until Xi, and now a clear move towards less openness and freedom. You seem very pessimistic about China’s future trajectory in general, and the economy in particular under the current model. Could you elaborate on that perspective?

Yasheng Huang: Let me be clear, China has many positive fundamentals, including entrepreneurship, human capital, and globalization — not just in terms of factories but also in human capital. China has progressed further in this regard than countries like Japan and many others.

However, I am indeed pessimistic about China under the current policy model. This model overemphasizes the supply side and underemphasizes the demand side. It places too much focus on industrial policy, high-tech development, and technological aspects while undervaluing grassroots entrepreneurship and bottom-up growth models.

I’m also concerned about the constricted political and ideological environment, as well as the geopolitical tensions between China and the West. It’s worth noting that the two generations of leadership after 1989 globalized the Chinese economy and research and educational enterprise, which greatly benefited Chinese society and economy. Now, we’re moving away from that approach.

In my book, I discuss the curious combination of worrying about a Soviet-style collapse while prescribing a Brezhnev-style solution. This is profoundly puzzling to me. To avoid a Soviet-style collapse, China needs to move away from the Brezhnev model of stagnation, political control, and economic control.

What saved China — and by extension, the Chinese Communist Party — was entrepreneurship, private sector development, economic dynamism, and globalization. I find it perplexing that there’s now an argument for saving China from the private sector and globalization when these factors were delivering political benefits to the system.

As Deng Xiaoping famously said, “When you open the window, some flies will come in, but so will fresh air (打开窗户,新鲜空气和苍蝇就会一起进来).”

If you focus solely on the flies without considering the fresh air, you’re not striking the right balance. These are the reasons for my lack of optimism.

Ilari Mäkelä: You make an interesting point in your book about this problem — the Chinese Communist Party genuinely believes that much of the growth has been due to their successes, thinking that with more power, they can do an even better job. But what you observe is that China’s significant growth was actually enabled by a hidden pluralism — through globalization, academic cooperation, the influence of Hong Kong and Taiwan, and various other factors. China had many more pluralistic conditions than its outwardly authoritarian appearance suggested, and these conditions are now being eroded.

Yasheng Huang: I’m constantly struck by the fact that Xi Jinping and many Western observers agree perfectly on this point. They all believe that it was the infrastructure, the power of the government to leverage data and financial resources, and the government’s organizational capabilities that delivered economic growth. They see eye to eye on this matter.

This view was pervasive among policy elites in China even before Xi Jinping, though Xi has taken it further by targeting the private sector as well. The fundamental problem with this view is that when China fully embraced it, Chinese productivity collapsed, even as GDP continued to grow rapidly for a while.

But who cares about productivity when it’s not a number you see on TV every day? We have Western analysts who just look at GDP, and anyone familiar with the Chinese economy would first question the veracity of the GDP numbers. This is not just a problem in China; it’s a problem in the West as well. Whenever I see someone being interviewed on prominent forums saying, “I know China because I have met with Chinese leaders,” I begin to worry about their perspective.

Jordan Schneider: Another problem with changing the constitution is that it introduces new succession problems.

Yasheng Huang: Indeed. Autocracies can build, at least Chinese autocracy can. However, autocracies suffer from succession issues. One inevitable problem faced by many autocracies is how to transfer power from one leader to another.

Imperial autocracies didn’t have to deal with this problem because power was passed to the son. In China, it was even more restrictive — only the oldest son was the legitimate heir. The rules of the game were very clear.

Autocracies often fail because the rules of succession are unclear. Gordon Tullock famously noted a difference between some autocracies and those he observed in Latin America (Brazil, Argentina) in the 1970s. There, the autocracies didn’t translate into bigger political problems because they had term limits.

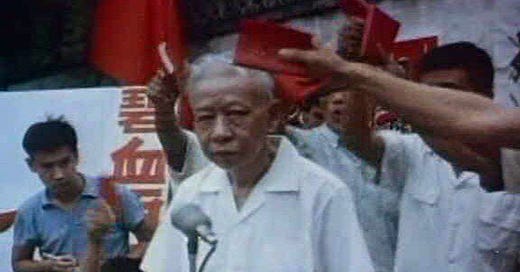

China successfully transferred power three times in a row under term limits — to Jiang Zemin, then to Hu Jintao, and then to Xi Jinping. Before China instituted term limits, it was chaotic, as seen with Lin Biao 林彪, Liu Shaoqi 刘少奇, and Hua Guofeng 华国锋.

In my book, I call this “Tullock’s Curse.” China was suffering from this curse before term limits. We thought the problem was resolved when China instituted term limits. The worry now is that Tullock’s Curse may return because China abolished term limits in 2018 through constitutional revision.

We don’t know what will happen in the future, but if I were to bet on one sure source of instability and chaos, it would be this. Economically speaking, they are also adding complexity to the future. The political instability and uncertainty will likely stem from this change, though the exact timing is unpredictable as it’s largely driven by the health of individual leaders.

Jordan Schneider: People often overlook that during the post-Mao era and Deng Xiaoping’s rise to power, China initiated its only war. Joseph Torigian argues in his book that Deng’s decision to start the war with Vietnam, despite opposition from the Politburo and PLA, was a way for him to solidify his control over the system. This demonstrated that he was in charge and could command others to follow his orders.

While Deng had his reasons, one of them was partially to establish himself as the top leader in the new era. I’m curious about your reflections on the invasion of Vietnam and to what extent messy transitions lead to international adventurism.

Yasheng Huang: That could be correct. However, the current discussion about Xi is quite different. Deng was a contender at that time, not yet the supreme leader. Now, the speculation is about whether Xi will attack Taiwan.

Jordan Schneider: Exactly. The scenario I find more concerning is not Xi waking up one day and deciding to do something, but rather enough chaos in the immediate aftermath of Xi that there’s a domestic political reason to become more aggressive than in the past.

Yasheng Huang: I see. That’s interesting — a contending successor considering such a move.

Ilari Mäkelä: Or we might get material for an entertaining film like “The Death of Stalin,” but called “The Death of Xi."

Jordan Schneider: Let’s discuss the challenges of succession when you can’t rely on the firstborn and you’ve removed legitimacy. What new complications arise even if the leader tries to choose a successor?

Yasheng Huang: There are numerous complications. One is the lack of trust. In that type of system, with no clear rules, as soon as you designate someone, you also empower them. The reason why there’s no clear succession plan is that leaders always prioritize control and power. Essentially, when making a succession decision, you’re also deciding to weaken your own power. You’ll never feel entirely comfortable with that decision.

The outcome depends on the individuals involved, but there are structural tensions built into the system. From the potential successor’s perspective, once nominated, what do you do? It’s never a comfortable position because the leader doesn’t fully trust you and will watch your every move. On the other hand, if you don’t act, that may be used against you.

Two likely scenarios often occur, and they’re correlated. First, you make multiple mistakes. Because of these mistakes, you delay the decision until the last moment, as Mao did. Mao appointed Hua Guofeng almost on his deathbed. At that point, your mental and physical capacities are diminished, increasing the probability of making the wrong decision.

Mao made the wrong choice because he thought Hua would continue his policies, but he didn’t anticipate that Hua would remove the Gang of Four. It turned out that Hua was a Maoist, but he disliked the Gang of Four. By removing them, Hua inadvertently empowered Deng Xiaoping.

These theoretical dynamics play out and almost guarantee an uncertain, chaotic process. We can’t predict the next specific scenario due to the many unknown individual characters involved. However, we can be certain about the lack of stability and certainty.

Chinese Nationalism and Rethinking Terms for Engagement

Jordan Schneider: Let’s conclude with U.S.-China relations. You point to an almost original sin of U.S.-China engagement from post-Tiananmen through the mid-2010s, where the engagement strategy wasn’t really a strategy but more of a tautology. To have an engagement strategy, you also need a disengagement strategy, which the American political system never really embraced in the 1990s, 2000s, and early 2010s. Could you elaborate on what could have been?

Yasheng Huang: The engagement strategy was originally justified on political grounds rather than just economic ones. If you read the speeches by Bush and Clinton, who laid out this strategy, they justified it in political terms. It was also in the aftermath of the East Asian Tigers transforming into democracies. They imagined a similar trajectory for China 20 years in the future.

Once the strategy was in place, focusing solely on the U.S. side, they let it run on its own. It became all about economics, even though the original justification was political. The implementation focused on financial access to the Chinese market, investments, and companies like GM. It was all about economic and business interests. They never really leveraged the U.S. economic presence in China to accomplish the original political justifications they laid out.

A smarter political strategy would have been to deepen information industry engagement with China rather than simply focusing on products and finance. When examining the history of U.S. interactions with China regarding market access, it was all about companies like GM, GE, Goldman Sachs, or Morgan Stanley. When Google was leaving China or the New York Times was banned, the U.S. didn’t say much. The U.S. didn’t try to negotiate on behalf of Facebook or other social media companies to maintain their presence in China.

Some might argue that would have been worse, but in China’s closed environment, having the diversity of Google and Facebook would have been a plus in terms of political and ideological space compared to just having Baidu and Tencent. The U.S. never really advocated on behalf of the information industry. They advocated for Wall Street and big manufacturing companies through Treasury Secretaries and Commerce Secretaries.

This was an unthinking strategy. They never linked economic activities with potential political spillovers. I would argue that the information industry would have provided more political spillovers than finance and big manufacturers.

Another critique is that it may be inherent in the nature of the process. It’s difficult to disengage, it’s easier to engage more. Sometimes democracies must recognize that there are decisions they don’t control. Once the cat is out of the bag, it’s out. This is an asymmetrical game between China and the U.S.

China can choose to engage and disengage, but we cannot really disengage once engaged. Given that’s the case, we need to think about better ways to engage.

Jordan Schneider: You make an interesting argument that America was either shooting for the moon rhetorically, talking about how China needed to be an open liberal democracy, or just saying it would happen in time. Instead of focusing on making China into a Jeffersonian democracy, they could have aimed for something like Taiwan in the 1970s or Korea in the 1980s, which, while not entirely liberalized, would have been significant progress.

You also make interesting arguments about reciprocation in academia. The analogy of MIT only doing exchanges with Saudi universities on the condition that female Saudis are equally eligible demonstrates the type of things the U.S. could have done.

Deng understood deeply that he needed Western investment, education systems, and management practices to upgrade China’s ecosystem. Perhaps if the cards had been played differently in the early 1990s, we wouldn’t have reached the situation where, by the mid-2000s, Chinese leaders wouldn’t just shrug their shoulders at Western concerns.

Yasheng Huang: It’s puzzling. They aimed for the moon and then settled for nothing. Couldn’t there have been something in between? The U.S. administration also handled this poorly. Because the original justification was political, they felt the need to show concern for human rights. They would meet with the Dalai Lama and some Chinese dissidents. These symbolic measures alienated many Chinese.

Instead, they could have emphasized smaller steps. For example, convening conferences on the rule of law and commercial rules of the game. They could have insisted on reciprocity — “You have Confucius Institutes at our universities; we should have our own institutes at your universities, operating with the same freedoms as Confucius Institutes in America.”

They could have pushed for equal treatment of American newspapers in China, just as People’s Daily is available in America. They could have insisted on more balanced exchanges of scholars and students. We didn’t do any of that.

Ilari Mäkelä: When it comes to issues like Xinjiang, the U.S. has done more than just meet with high-profile Uyghurs. They’ve tried various approaches, including targeted sanctions. Do you think the U.S. could do better on issues like Xinjiang? Or is there fundamentally only so much you can do from the other side of the world on such a massive issue?

Yasheng Huang: We’re returning to the meta-questions about engagement and disengagement. The Xinjiang issue now involves punishment and disengagement. My earlier point was about whether there was a way to make economic engagement produce more intellectual and ideological space compared to how we actually conducted ourselves. Xinjiang represents China moving further down a politically restrictive path, and China today is even more politically controlled than before. Now there’s a legitimate question: can we still engage with a country that has gone as far down this political path as China has? It’s a tougher issue now than before, and I don’t have a clear view on whether we should still engage or stop engagement altogether.

Jordan Schneider: US presidents meet with the Dalai Lama and fight for factories and financial access rather than for the rights of the New York Times in China, and the reason is American domestic politics. Tibet was a big issue in American politics in the early and mid-1990s, and money matters in Washington. The strategy you’re laying out, which bets on creating a Chinese intelligentsia that would yield dividends 10, 20, 30 years down the road, would have required a pretty enlightened viewpoint.

One of the concerning things about the future is the possibility of losing an entire generation of liberal or open-minded thinkers in China. It’s striking that figures like Zhang Yiming 张一鸣 and Jack Ma were pretty open to the West and had spent time here. You can find old WeChat posts from CEOs of the new generation of tech companies talking about wanting a more liberal order. The worry is that when you lean too far away, you lose any of that influence. I’m curious about your reflections on that or the fact that the vast majority of critiques in China come from the left rather than the right, arguing that the party isn’t doing enough for poor people.

Yasheng Huang: It’s a bit like the U.S. in the sense that right-wingers can say all sorts of things without facing consequences. In China, the rhetorical primacy lies with the nationalists. I consider myself a leftist, so I won’t dignify those people with that label. I believe many of them are more similar to right-wing nationalists in the West than to ideological leftist-leaning people in the West.

Leftists actually care about people — unemployment, inequality, the gains of the people. I don’t really see that in the rhetoric of many of these “little pinkies” (young Chinese nationalists). They care about the nation, nationhood, historical glory. These are classic right-wing nationalistic rhetoric focusing on abstract power. They care about bragging power, which fundamentally aligns with the ruling ideology, which I classify more on the right-wing nationalistic side than on the leftist side.

It’s really just this pursuit of power, the pursuit of abstraction, the pursuit of nationhood. For example, unifying Taiwan — what does that give Chinese people in terms of improving their lives? I would argue very little. But somehow, unification of the country under the same political system is seen as enormously glorious.

That view is really a right-wing, nationalistic view. My temperament and way of thinking are fundamentally different from that. I care more about tangible things. Maybe I’m small-minded, but I don’t think about the nation in those abstract terms.

Jordan Schneider: One of your interesting arguments is that Washington should focus less on ethnic minorities in China and more on the persecuted CCP cadres and what they could gain from relative liberalization. Can you elaborate on that case?

Yasheng Huang: Many CCP elites have actually suffered terribly in the end. Look at Liu Shaoqi, or the four million people purged under Xi Jinping on corruption charges.

It’s interesting that quite a few of these people could trash the West and the United States all the time, but during moments of personal crisis, they actually turn to the West. The police chief of Chongqing, when being chased by Bo Xilai, defected to the U.S. consulate in Chengdu. He didn’t go to the Iranian, Russian, or North Korean embassies. He came to the U.S.

Elites park their assets in the United States and send their children to U.S. universities and high schools.

I think the West should craft an argument that appeals to CCP elites, rather than crafting an argument designed to appeal only to Tibetans and Uyghurs.

The simple fact is that in China, the Cultural Revolution didn’t single out Tibetans or Uyghurs.

I’m of Han ethnicity, and my parents suffered as much as Tibetans or Uyghurs did. So why do we insist on this ethnic line, which will antagonize 95% of Han Chinese, rather than relying on arguments that Han Chinese can also relate to?

We should think of an argument that plays more in that direction. I’m not sure exactly what that argument would be — it’s above my pay grade, as I’ve never been asked to create a policy brief for the Secretary of State. But in terms of general philosophy, we should craft an argument that appeals to more people than just ethnic minorities.

Jordan Schneider: I love this. You have a few great examples, like Liu Shaoqi waving a copy of the constitution and protesting that he had rights during a struggle session. Or Gu Kailai 谷开来, Bo Xilai’s wife — who ordered a hit and then ended up getting a commuted death sentence — writing in the late 1990s that the American judicial system is so slow.

It’s always, as you say, that democracy and the rule of law are like insurance policies. When you don’t know whether you’re going to have an accident, the smart thing to do is take out insurance.

Yasheng Huang: Why not make that argument to your Chinese counterparts? The Jesus analogy you mentioned is apt — it’s like becoming Catholic on your deathbed.

Jordan Schneider: You spent the past year in Washington. What are your thoughts and reflections? What surprised you most about the way the city views China?

Yasheng Huang: Living here, I’ve come to appreciate the deep and increasing complexity of geopolitical challenges and tensions more than I would just working in academia. These are complex issues. While I can be critical in my book, I do want to acknowledge that there are people in this city who want to do good. We do hear about sometimes over-the-top rhetoric against China, but there are also people who want to strike the right balance. They need ideas, advice, and inspiration.

I believe there’s room for some sort of reset and rethinking about China, hopefully in a more imaginative way. I don’t have high hopes, regardless of who wins the November election. If Trump wins, then forget about it. But on the Democratic side, I do hear more views acknowledging that while China poses geopolitical challenges to the U.S., there are areas where we have to collaborate with China. That’s just reality. Striking the right balance is an art rather than a science, but it would be beneficial if the Washington political establishment could be more open-ended in their approach.

Jordan Schneider: It’s interesting that you mention Trump. In your book, you note that Trump was the first president to introduce the idea of reciprocity and conditional engagement. While he might not have set the conditions for academic exchanges or fought for the New York Times, there is something to be said for him breaking the paradigm that wasn’t really going anywhere.

Yasheng Huang: I agree with that. We could work on that approach and make it more productive, not in the way he did it. He changed the rules of the game, and that’s the framework we have to accept now. But we can play the game better than he did.

Ilari Mäkelä: In my show on humans, I always finish by asking my guests: How has all the research that you’ve done and all the work that you’ve done shaped your outlook on humanity?

Yasheng Huang: I’ve come to appreciate surprises, contingencies, and the lack of predictability in history and in the world more than I did before. In a narrow academic environment, we always work on universal regularities and determinism. But history has taught me that there are consequential turning points. At the time, we didn’t think about them that way, but they could turn out to be significant. Now I have the mental habit of trying to think about issues in those terms and asking myself if a particular event is likely to be one of those consequential moments in history. The answers almost don’t matter, but I think it’s good to pose that question all the time.

Regarding humanity, I believe we are more complex than economists assume, and we sometimes behave in ways that are not terribly rational. This emphasizes the importance of the systems we create. The way I think about systems is that they place boundary conditions on either rationality or irrationality. How do we design a system that maximizes rational thinking and action while also alleviating the downsides? That’s a question that goes beyond the simple dichotomy of autocracy versus democracy. You need to think about how to balance competing forces — rationality vs irrationality, and scale vs scope. This is something I wasn’t thinking about before, and this research has taught me that it’s probably the right way to approach understanding the world and ourselves.

Yasheng Huang’s song choice:

The failure of reform in China discussed in clear-eyed detail here. Thank you.

Good one. Wish I had some bright ides for you.