Wolf Warrior Diplomacy Faces a Reckoning and How the House GOP Would Take on China

Plus: Climate Change Commitments, Jews Eating Pork in China, and the Chinese Student Pipeline Drying Up

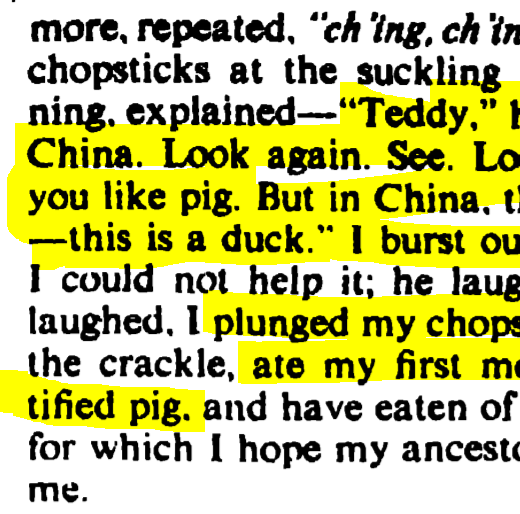

2020 is the worst year for the CCP diplomatically since 1989 and Tiananmen. A new Pew poll surveys the damage.

I love how Japan is the only country that hasn’t budged at all … because the Japanese already couldn’t stand China before 2020.

Despite its current strategy clearly failing abroad, the CCP shows no signs of adjusting its diplomatic approach. Why? Because the Wolf Warrior strategy has its roots in Xi’s personal leadership.

The following piece by David Bandurski deserves quoting at length.

“Wolf warrior diplomacy” is not fundamentally about diplomacy at all, but about a deeper shift in Chinese politics, one that should invite profound global concern. It is ultimately about the rise of charismatic politics in China, about the erosion of collective leadership in favor of a cult of personality around Xi Jinping. In today’s China, Xi Jinping is the pack leader, and his instinct for power drives the country’s governing calculus, and also its foreign policy.

Chinese diplomacy today is driven primarily by the internal need to elevate the person and power of Xi Jinping himself, to pledge allegiance and build on his prestige.

At one point, Xi’s topic was the collapse of the Soviet Union, a cautionary tale that still looms large within the CCP. “Why did the Soviet Union disintegrate? Why did the Soviet Communist Party collapse?” Xi asked. The Party had lost sight of its values and convictions, he said, and had failed to maintain its grip on the armed forces. In essence, Soviet leaders had grown soft. Then, as Xi summed up his lesson, came a line that epitomizes the ethos of his leadership, and also his approach to diplomacy: “The Soviet Communist Party surpassed us in terms of the proportion of party members [in Soviet society], but no one was a man, and no one came out to fight.”

Xi’s words on his southern tour in a sense foreshadowed what director Wu Jing would say after the release of Wolf Warrior II, that the purpose of the story was to “inspire men to be real men.” A brash and growling manliness, directed toward the defense of the CCP empire, is the spirit that defines diplomacy, and much else, in Xi’s China.

One year ago, Xi again made his appeal for manliness directly to CCP officials. “Leaders and cadres,” Xi said, “must persistently sharpen themselves on the grindstone of major struggle… daring to show their swords on major issues of principle.” Shortly after this speech, the Party’s official People’s Daily newspaper admonished officials, particularly younger ones, for being “weak-kneed and unwilling to fight.”

Xi Jinping is the country’s alpha male, the leader of the pack, determined to inspire a fighting spirit in the Party’s ranks. And he is the reason that China’s hackles have gone up.

The great irony of the entire Wolf Warrior arc is that the old playbook is still extremely effective. It doesn’t just work on the likes of Secretary Mnuchin and Wall St. titans like Stephen Schwarzman and Ray Dalio (his latest on US-China is a real doozy). As a new NYTimes piece shows, Liu He was able to use lines like “we’re old friends,” “China is still very poor,” and “I’m part of a reform faction that needs your support to show we can deliver” to turn USTR Lighthizer from one of the staunchest anti-China advocates to a voice for calm on trade policy. This is masterful diplomacy and if only Xi would ‘Let Liu He Cook’ he and his ilk in MOFA could probably accomplish wonders abroad.

Lingling Wei and Bob Davis in their new book Superpower Showdown give an insider’s take on just how Liu He worked his magic.

[midway through the trade negotiations in 2018] Lighthizer had come to trust and respect Liu as a committed reformer…Lighthizer sounded sympathetic about the political constraints facing Liu and other negotiators. “We tried to accommodate changes that China would ask in the text that we thought were needed for their own purposes,” Lighthizer told reporters. “But these are substantial and substantive changes. And really I would use the word, sort of reneging on prior commitments.”

In some surprising ways, though, the Trump administration began to resemble the Clinton administration on China trade. Trump officials, like Clinton officials before them, had come to believe that the only way to change China was to line up with reformers and try to help them with their internal battles. Chinese leaders had to believe that change was in their interest and wasn’t being forced upon them from outside, officials in both administrations learned. “You can start the process of reform,” says Lighthizer in an interview. “The things we’re talking about are the things a reformer in China would agree to.”

Late in 2019, Liu He and Robert Lighthizer, opposing generals in the trade war, had a conversation that underscored the difficulty Americans face in changing Chinese behavior.

Lighthizer, a history buff, told Liu he had spent many hours studying Chinese history and society. “I know enough about China to realize that I don’t have any idea of how you think about things,” Lighthizer said.

“That’s the beginning of wisdom,” Liu replied.

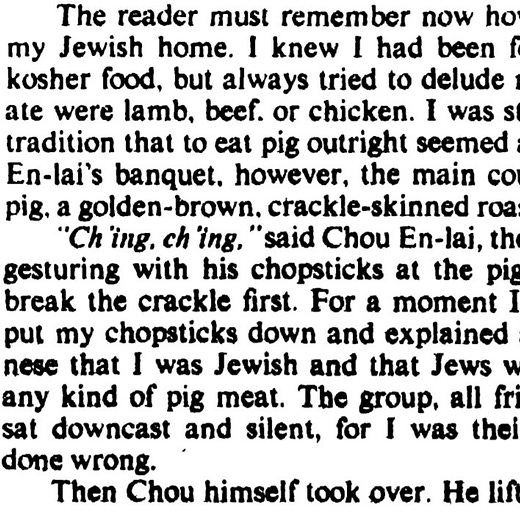

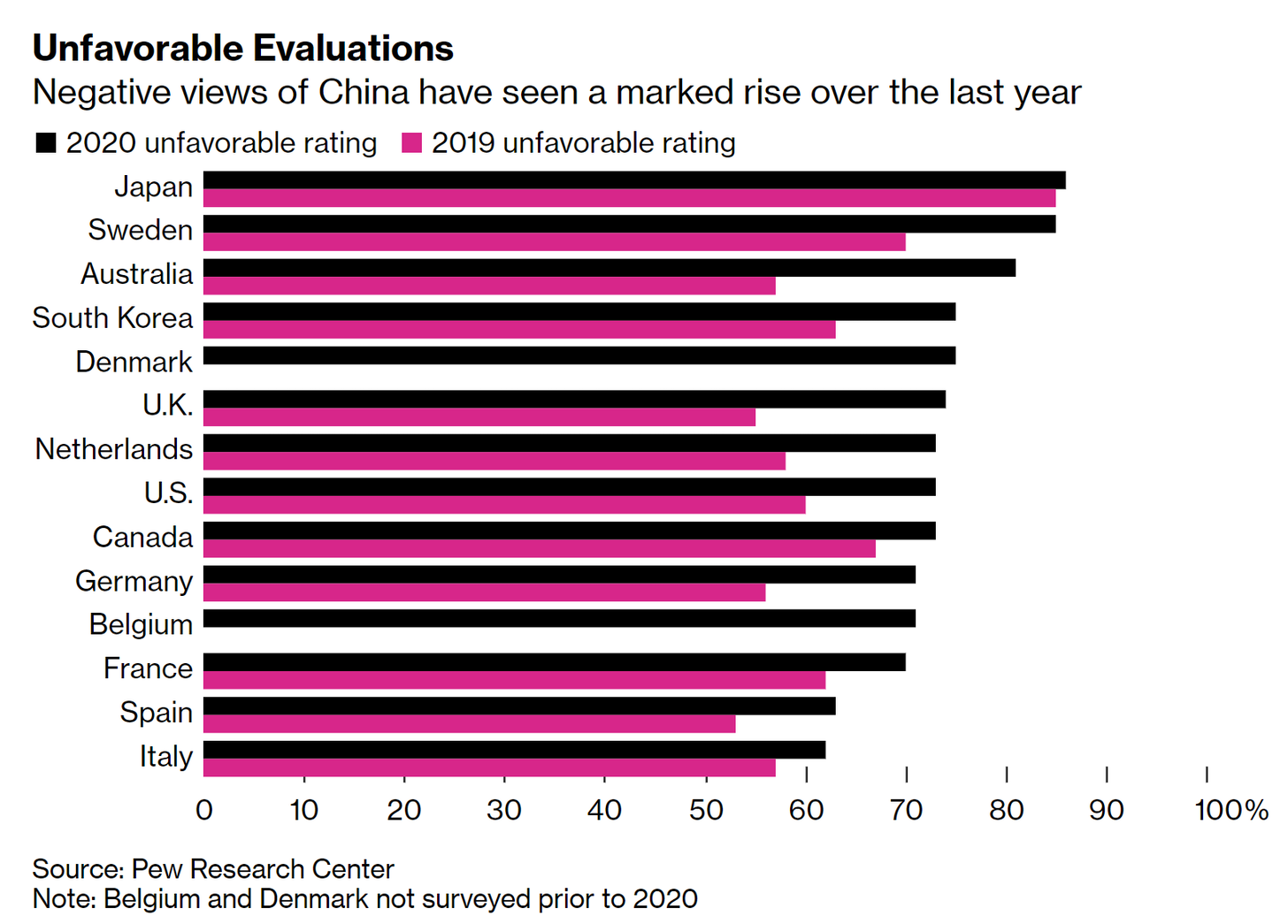

Zhou Enlai was using the same line as far back as the 1940s! As American journalist Theodore White wrote, reminiscing on his interactions with Zhou in Chongqing during WWII:

GOP China Task Force Report

Coming out of the House last week was a report authored by Republicans who hail from the whole gamut of committees, with over 150 recommendations for how to address the “China threat.” Democrats were initially set to join but dropped out of this exercise because, according to WaPo reporting, “they believe the China issue is just too politicized.” I read through the whole thing so you don’t have to.

Ideological Competition

Recommendation: The Administration should clearly and publicly state an intention to break the CCP’s totalitarianism. [...] America’s goal must not be indefinite coexistence with a hostile Communist state, but rather, the end of the Party’s monopoly on power.

Pretty bold to say what amounts to regime change should be the goal of U.S. policy.

Recommendation: Congress should pass legislation calling on U.S. media organizations to disclose when they receive payments for advertisements from companies or news outlets with strong ties to adversarial governments, such as the CCP.

Seriously, enough already with the giant China Daily inserts in the Washington Post and New York Times.

Supply Chain

Lots of spending mostly to plug US vulnerabilities to Chinese export controls around rare earths, semiconductors, and pharmaceuticals.

National Security

Recommendation: The Administration should continue its efforts to clarify and reassert the U.S.’ longstanding security commitments to Taiwan.

This and other recommendations underline just how uncomfortable Congress is with Trump’s seeming downgrading of Taiwan. However, when push comes to shove, if the President is perceived as not credibly committing to the defense of the island, I’m not sure any legislation on this issue will matter.

Recommendation: Congress should pass H.R. 7224, the End Communist Chinese Citizenship Act, which prohibits members of the CCP[…] from obtaining green cards. H.R. 7224 would, however, maintain the exemption for involuntary membership, which allows green cards to CCP members when an affiliation was either against their will, or only when younger than 16 years of age.

Note that this is less extreme than what the White House initially floated in July 2020, which was not a green card ban but a full immigration ban on the over 90 million CCP members. Also nice of them to think of the kids; the Young Pioneers and Youth League’s membership rolls include the vast majority of young people in China.

Technology

Proposes increased funding and an improved regulation for 5G, quantum, autonomous vehicles, cyber, biotech, advanced manufacturing, space, as well as a push on international standards-setting.

Economics and Energy

Pushes to counteract the Belt and Road Initiative, boost U.S. LNG, and continue aggressive export restrictions, and abundantly fund CFIUS.

Encourages the SEC to force more disclosures on Chinese companies with regards to their accounting standards and their relationships to the Chinese government.

Competitiveness

Suggests cutting taxes on R&D, putting an additional $100 billion towards R&D, and improving the patent system.

Recommendation: The U.S. immigration system is a generous one that must be updated to meet the needs of the modern economy. This means making a shift towards a more “merit-based” immigration system that remains mindful not to harm the employment prospects of qualified American workers, particularly as the economy reopens in the aftermath of COVID-19.

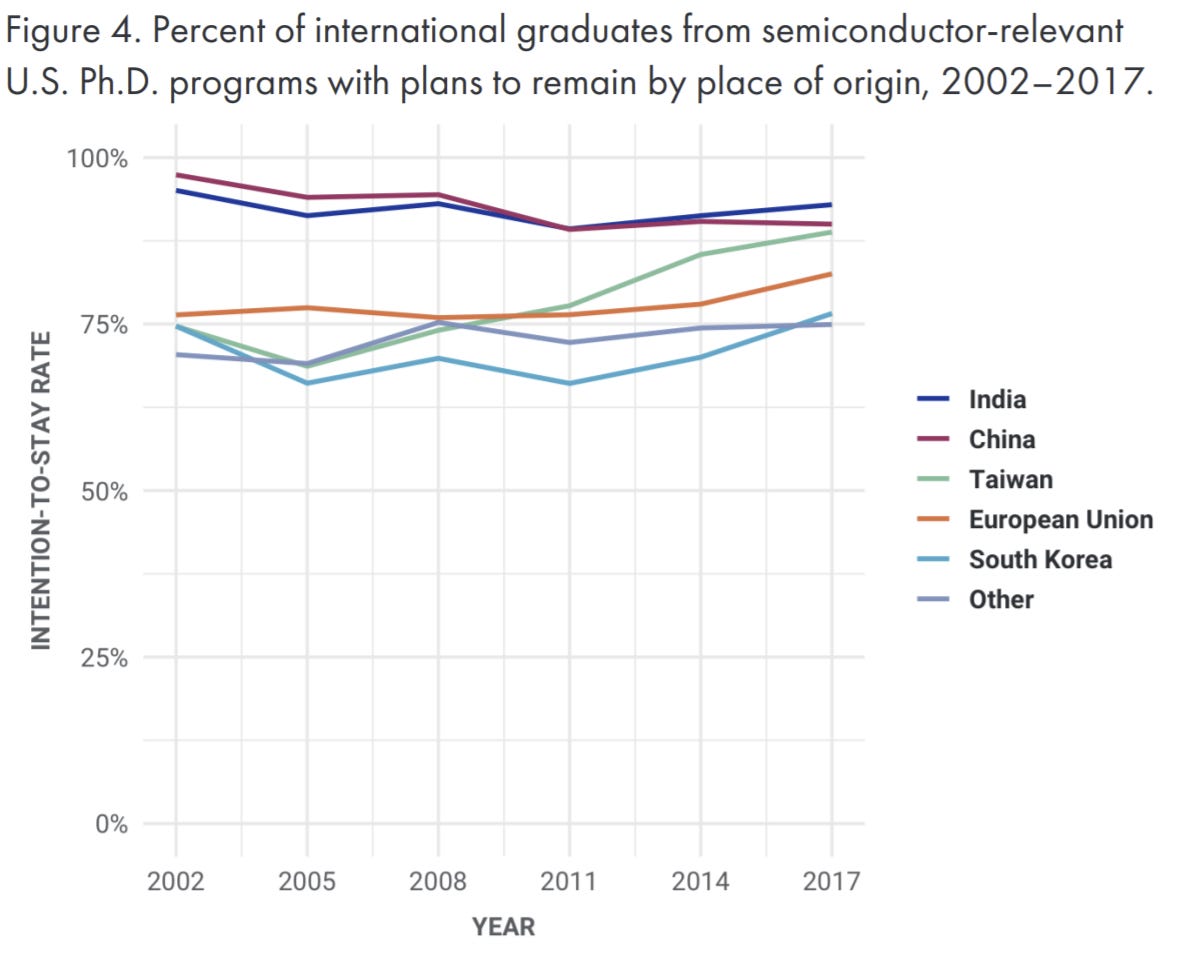

There’s some serious cognitive dissonance when it comes to immigration. The report does acknowledge that “in the near and medium term the U.S. will remain reliant on foreign talent” and that “the U.S. cannot afford to take for granted that it will remain the destination of choice for STEM students.” This of course does not acknowledge the long-term damage done by the student-visa scares and H1B travel bans. Stay rates of STEM PhDs, while dipping almost certainly in response to Trump policies, are still over 90 percent for many of the U.S.’ largest feeder countries.

Attracting and retaining foreign—and yes even mainland Chinese—STEM talent is central to innovation, and the decreased attractiveness of the U.S. to foreign talent shouldn’t be taken lightly. This document spends far more time on topics like beefing up DoJ enforcement than thinking about pull factors. While combating counter-espionage is an important policy goal, it’s the exact sort of thing that will make foreign researchers feel less comfortable and will drive down those admirable stay rates. What would make for a more effective policy is grappling with those trade-offs and endorsing a serious pro-innovation immigration policy that would make it easier to obtain entrepreneurship visas, expand H1Bs, and provide a more reliable and straightforward path to permanent residency.

While the ideology section may be a litte harder hitting, overall this document is not all that dissimilar from the Democrats’ version of a China bill from earlier this month. I’d expect this sort of legislation, combined with the CHIPS Act for the semiconductors and the $100 billion towards National Science Foundation R&D, to move forward reasonably soon.

So how did we get to this point of rare consensus? Trump, by kicking off a trade war and elevating hardliners like Navarro, Lighthizer, Ross and later Wray and Pompeo, certainly expanded the Overton Window on China policy. What really sealed the deal in turning China into a bipartisan issue was the NBA’s free speech blow up, the Hong Kong crackdown, to some extent Xinjiang, and most importantly COVID.

These bills illustrate just how poorly Xi played his hand of late. Chinese policymakers have been trying to develop technological independence since Mao, and American think tanks have spent decades unsuccessfully pleading for more R&D funding. Only in the past year have they gotten any traction. To be sure, there is a part of this that was inevitable. As Chinese tech firms grew larger and more globally competitive, the U.S. was bound to feel threatened much like it did with Japan in the ‘80s. But Japan was able to push off the backlash much longer than the CCP, in part by leveraging a better understanding of the U.S. system to play a much more subtle game. Here’s an excerpt from Pat Choate’s 1990 Agents of Influence, which focuses on Japan’s efforts to minimize an anti-dumping response with regards to TVs and VCRs. In return for support in GATT negotiations,

[Carter’s USTR] Strauss signed a secret side letter with the Japanese and agreed to provisions that would hamper American actions on television matters for years to come. Strauss committed the United States to: Limit the ITC investigation of predatory pricing by the Japanese cartel […] Ignore monopolization charges against Japanese companies when they were acting domestically in accordance with the directives of the Japanese government [… and] inform the Japanese government quickly of any significant findings arising from U.S. investigations of the TV matter, and be open to informal Japanese communications (that is, create a back channel).

A year and a half after Strauss made his secret commitments, Rep. Dan Rostenkowski (D-Ill.) learned of them. At a Ways and Means committee hearing, he asked Strauss for a copy of the agreement, which he was given for the record. Still, the U.S. government remained committed to its deal.

Strauss was, to say the least, badly outnegotiated. Indeed, thanks to Strauss, the cartel achieved a political solution to most of its legal problems in a single bold stroke—and at virtually no cost. It now had everything it needed to complete its assault on what remained of the American television industry.

Instead of keeping his head down and slyly pursuing policy, Xi had major public rollouts of the Made in China 2025 and Ten Thousand Talents Plan. Xi had domestic reasons to make a big public show of these programs in order to concentrate his bureaucracies’ efforts and demonstrate that he had a handle on things when the ZTE ‘Sputnik moment’ hit. However, had he just publicly framed his tech ambitions for China a little less ambitiously, and even just by simply sticking to boring names like the 863 Program of the late 80s, he may have been able to push off the U.S. response a handful of years, in turn buying Chinese firms and researchers more time before the U.S. starts to get its S&T house in order.

Please consider supporting ChinaTalk

China Twitter Tweets of the Week

Thread