Why America Didn't Invade Taiwan

Operation Causeway in WWII and what that means for Xi

One does not simply invade Taiwan — but George Marshall once thought long and hard about it. In 1944, in the middle of the island-hopping campaign, American war planners set their sights on Japanese-controlled Formosa.

What did the American invasion plan look like? Why did Marshall decide to go another route? What lessons do this and other amphibious invasions hold for Taiwan’s current force posture?

To discuss, ChinaTalk interviewed US Army Field Artillery Lieutenant Colonel J. Kevin McKittrick, currently at the Air War College in Alabama and a veteran of multiple deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Co-hosting today is our resident Taiwan consultant Nicholas Welch.

We discuss:

The US military’s aborted plan to invade Taiwan during WWII;

Why bigger is better when it comes to amphibious assaults;

What the US got right and the CCP gets wrong about civil-military relations;

Taiwan’s defense concept, and the opportunities presented by “operational pause”;

The awful, unending relevance of traditional artillery in modern war;

And why the US doesn’t need its own “rocket force” … yet.

“As soon as Taiwan is reunified with mainland China, Japan’s maritime lines of communication will fall completely within the striking ranges of China’s fighters and bombers … Japan’s economic activity and war-making potential will be basically destroyed … blockades can cause sea shipments to decrease and can even create a famine within the Japanese islands.”

The Unsinkable Aircraft Carrier

Nicholas Welch: In August 1944, Operation Causeway surfaced among military planners and the Joint Planning Staff. Can you walk us through what the United States was thinking at that time in World War II?

J. Kevin McKittrick: In World War II, 1944, we’ve already started the Pacific island-hopping campaign. The ultimate goal of our war in the Pacific was the unconditional surrender of Japan. At this time, it’s how do we do that? How do we get close enough? How do we get within range?

One of the major options that started to percolate amongst the staff is, “Hey, we should go and seize Formosa.”

There are a number of reasons why Formosa provided a good choice for them. Really, they discuss three major advantages:

Seizing Formosa allows the US forces to cut off strategic lines of communication for Japan with the rest of their empire, especially in Southeast Asia.

It puts them in close proximity to mainland China, which helps alleviate the pressure on the Republic of China’s armies that are also fighting the Japanese.

It would enable allies to put long-range bombers closer to Japan to start the main attack on the Japanese homeland.

Formosa provided an ideal location for all three of these things. It wasn’t by any means the only option, but it was really the one that checked the most boxes for success. This idea got enough traction — so much so among the Joint Planning Staff — that in a lot of the historical documentation, they refer to future operations in the Pacific as “operations subsequent to seizing Formosa.”

It certainly carried a lot of weight on the Joint Planning Staff, as well as with some senior leaders, most notably Admiral Ernest King. Obviously, there were some leaders that were always against that plan, General MacArthur being one of them.

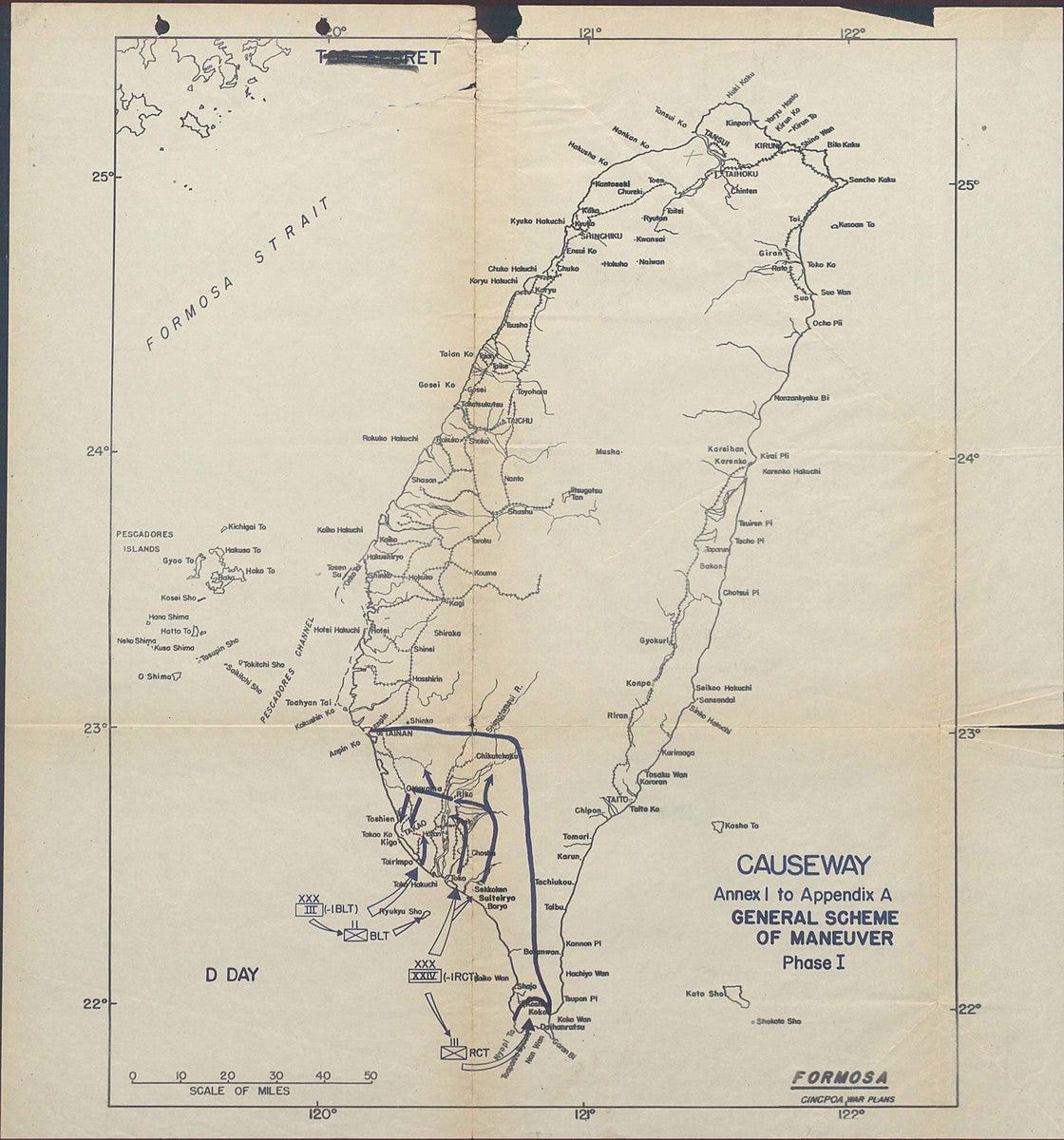

Nicholas Welch: Let’s talk about what this plan actually looked like. Discussions began in 1943, and an initial plan emerged in June 1944, which was then revised in August 1944. Something interesting I saw in these plans: they were concerned with the occupation of only southern Taiwan, not the entire island.

They would start at Gaoping River 高屏溪 and then go up to Tainan 台南, but no higher. The plan was to move south all the way to Kenting 墾丁, but only as far north as Tainan. Why was the US interested, at least initially, in only taking a portion of Taiwan instead of the whole island?

J. Kevin McKittrick: Great question. Initially, they focused on the southern portion of the island, primarily to establish the air bases on Taiwan proper. They also planned Phase II of Operation Causeway, which involved seizing the port of Amoy [modern-day Xiamen 厦门] across the straight in mainland China. That port really just provided better naval facilities, better ports overall, as well as adding some pressure to Japanese forces on the mainland. The way it was originally designed, we can get both objectives.

It was also a question of forces available at the time with the conflict still raging in Europe and the Pacific. We had a Europe-first strategy.

What you’ll find with most war plans is that resource constraints play a large factor in what is feasible at a given time.

Nicholas Welch: This plan of taking only part of Taiwan had been changed by September 1944. General George Marshall stated that the requirement of Operation Causeway had changed, and that now they wanted to take the whole island.

Can you speak about why the United States changed its position actually somewhat quickly — from August to September 1944 — from taking only part of it to the whole island, and how that affected the force ratios they were thinking about?

J. Kevin McKittrick: It really just came down to the question, “How do we only secure part of the island?”

As part of the island, some of your best defense is the ocean — plus the jungle and mountainous terrain, an ideal location for any remnant forces on the island.

This was discussed by the Joint Planning Staff. By the time General Marshall got to the decision, he really saw the only feasible course of action was to seize all of Taiwan. That came with additional ramifications. At that point, it really starts getting to what is actually feasible. Do we have the troop forces and resources required to achieve the overall goal?

It’s the Size of the Dog in the Fight

Nicholas Welch: Initially, the US was thinking they would have 304,000 troops to Japan’s 98,000. That’s a force ratio of 3:1, and that would probably give them success.

You have this quote in your report: “According to US Army doctrine, defenders historically have had over a 51% probability of successfully prevailing against an attacker that is three times as large.” Is that still conventional wisdom today? Was that conventional wisdom at the time? 51% sounds like a coin flip to me. You need a 3:1 ratio to have a coin-flip odds of success?

J. Kevin McKittrick: That’s a great question. The way I would view it is that it’s a good planning factor. When you’re planning an operation, if you want a moderate chance of success, an attack-defense ratio, all other things being equal, of 3:1 gives you about the right odds.

Historically, what you can see is — not only just for amphibious assaults but for other types of fights — that ratio plays out really well. There’s a great study done around 2002, a CNA study by Carter Malkasian. Really, it’s charting the pathway to operational maneuver from the sea. What it looks at is amphibious results all the way back from the 1940s up through the 1980s, taken a historical approach.

And in a lot of amphibious invasions — when you factor out the ones that were grossly overstrong or grossly underweight — 3:1 was the conventional wisdom that most attackers used.

The other thing important to remember about force ratio is that it depends what type of attack or operation you’re going to do. A deliberate attack-defense ratio is normally 3:1 — 3 attackers to 1 defender. If you go on the extreme scale of things and you want to do a lead-element penetrating an enemy force, the odds are more like 18:1. Likewise, if you’re just an attacking force that just wants to delay an action of an enemy, you can potentially do that with 1 attacker to 6 defenders. It really depends on what you want to do and how you play it out.

This is not some golden rule that always plays out. As we like to say, the enemy always has a vote — also terrain, weather, and multiple other factors. Some of the other factors that can play into it include

The impact of past engagements — are the enemies already battle-worn?

Then there’s the quality of leaders — leadership plays a large role in rallying troops.

There’s the morale of the troops. Are they willing to fight to the last man, as many of the Japanese defenders were at that point in the war, or are they war-weary and ready to throw down their arms?

Maintenance of equipment is another piece.

There’s also the time in position: if you have a longer time in position, you have more time to harden your site versus if you just occupied it.

I’d say, overall, force ratios are important as a planning factor, but they’re not the end-all-be-all. I would caution anybody to look at other factors. How are the forces arrayed? What is the overall operational goal? How are they employed on the battlefield?

Nicholas Welch: When I was reading through your report, it seemed as though the force ratios were decisive in ultimately calling this plan off. When the US decided they needed to take all of Taiwan, they would need to increase their forces by an additional 200,000 troops to 500,000 so it would have a 5:1 ratio.

They also knew that Japan was going to reinforce Taiwan by March of 1945 — that would bring the force ratios back to 2.5:1 or 3:1. So the US set an invasion date for December 20, 1944, like, “Okay, we need to go right now before Japan reinforces.” But for a variety of reasons, it just wasn’t feasible to move an additional 200,000 units before then.

It seemed like simple math determined the outcome of Operation Causeway. Is that a fair reading of what happened, or is there more to it?

J. Kevin McKittrick: That summarizes the majority of it, really. It comes down to the resource constraints. I would say those resource constraints touch mostly on the manpower available, but also the transport ships.

One of the keys for the assault force: the quicker you get the whole assault force on the ground, the higher the likelihood you’ll succeed. If it is staggered over a number of days and you don’t have the transport ships, you run into an issue.

It’s certainly something that you don’t want to mess up at all. That is one of the other challenges. But it wasn’t impossible. They had proven that and done this on numerous other islands.

The Greatest Generation

J. Kevin McKittrick: One of the things that interested me the most about studying this problem set was the decision-making behind it and the leaders in the room. You hear a lot of names that that are historic — King, Leahy, Marshall, MacArthur. These individuals were battle-tested over several years of conducting operations throughout the Pacific. Even in the European theater, Normandy had just happened.

Jordan Schneider: What is your professional view of the thinking and the quality of those planning documents? It’s one thing to second-guess them over time, but they already had four years of experience in fighting large-scale military maneuvers with the equipment that was going on at the time.

This seems like the highest possible level of military discussion that you can have in a fog-of-war situation. They already had a lot of case studies for thinking about the parameters involved — quite different from Putin thinking about invading Ukraine or China thinking about invading Taiwan in the 2020s.

J. Kevin McKittrick: In a lot of these planning documents and the minutes from the Joint Chiefs of Staff meetings, you can almost sense (I don’t necessarily want to call it frustration, but) an eagerness by some of the planners for a decision: “Hey, boss, can we make a decision and either go or not go?”

Marshall and Leahy and several of the other leaders in the room are exercising a little bit of patience with making that decision. They actually push back a little bit. “Well, when’s the latest I need to make a decision to get the requisite requirements in theater to do this?” It’s not until a later date. “Well, then do you really need a decision now, or are you just anxious to get one?”

I was impressed by the prudence and wisdom of these leaders — realizing that a hasty end of the war benefits everybody, but let’s not just go ahead and make a decision just to make a decision. Let it mature a little bit. Let us make sure we have all the facts on the ground and really make sure we pick the best path forward.

Jordan Schneider: It’s funny, because you talked about these serious people having serious discussions about force ratios and logistics and whatnot. Then, MacArthur, out of nowhere, is like, “We should do Luzon, we should do the Philippines” — because the election’s coming up, not because “I promised that we would, guys.” It’s a different wrinkle that thankfully Marshall ended up deciding against, however.

There are some interesting historical forks in the road here. Maybe the invasion of Formosa wouldn’t have worked, which is a scary line to go down.

If the invasion worked, it might have bolstered Chiang Kai-shek and allowed the Nationalist Army to secure mainland China and maybe change the course of the 1940s on the mainland.

The call they ended up making — to take the island of Iwo Jima — was maybe not necessarily the best one in the end. A lot of historians argue today that they could have skipped that island and gone on to the next one.

These guys aren’t infallible, clearly, but it is cool to put your head in the space of these decision-makers over this time period.

J. Kevin McKittrick: Absolutely. I think the MacArthur viewpoint is an interesting one. Before a lot of these documents were declassified, the standard view from historians was that he must have had a significant influence on FDR to really push for the Philippines-first approach. Obviously, there are some factors that made sense for a Philippines approach.

If you’re thinking about the loyalty of the native population, the Philippines would potentially be a little bit more loyal to US forces, because the US forces were there previously and now they’re liberating them.

They could say, “Hey, they may join our side” — whereas Formosa is an unknown animal at this time. You have the native Chinese population. You have the aboriginal populations that have been under Japanese rule since 1895. On the question of who’d resist a little bit more or less, you’d have to weigh a little bit on the Philippines side.

Getting back to my original point with the historical aspects: because a lot of these documents hadn’t been declassified until about the 1970s, the standard interpretation at the time was MacArthur had a heavy influence on it. Even today, a lot of literature does paint that as a key consideration.

Most of the literature nods to the major consideration being resource constraints, primarily troop numbers, but they put some weight on the political factors. But what I got going through the Joint Chiefs of Staff notes and the Joint Planning notes is not much mention, if at all, of any of that. Instead, it was really a military-focused discussion on what is the best way to achieve our ultimate goal of an unconditional surrender of Japan.

That discussion did not delve into what was best for reelection or how to placate MacArthur, who felt like he was indebted to take back the Philippines sooner rather than later. I just was impressed by how much of a strictly military focus the planning staff laid on the problem set.

Nicholas Welch: What institutional factors within the military allowed them to think so critically and objectively about this, despite the political constraints?

J. Kevin McKittrick: I would say one reason is our general tradition in the US military of civilian control. We’re not there to make political decisions or weigh political factors.

The other factor was some of the general officers of the era. Marshall is a key one. He doesn’t even vote in elections, because he believes that he needs to remain as apolitical as possible.

That’s a very extreme viewpoint of that, but I think there’s a case to be made for that. It’s some degree of, “I am here to serve my leadership, which is the civilian control of the military, and I will focus on military solutions. I will give my best advice to those civilian leaders. But at the end of the day, I’m here to accomplish the objectives the nation has laid out, which is the unconditional surrender of Japan.”

Political Leaders & Offensive Operations

Jordan Schneider: Historically, starting wars tends to be something that the political leadership drives.

Once you’re into these more operational decisions, three or four years in, your president or prime minister is going to be less involved. I don’t think Putin is sitting there saying, “We should go to Kharkiv instead of coming up from Crimea” or whatever. You tend to have these more theater or field decisions devolve to the generals in charge.

The scary thing about Taiwan and China today: we’d be at the start of a war, not in the middle of one when the invasion starts. You can’t necessarily point to five giant amphibious invasions that have happened over the past twenty years with relatively analogous military equipment for which we can debate the attack-defense ratios.

Given all that uncertainty, what can we know about the force requirements to do an invasion across the Taiwan Strait today?

J. Kevin McKittrick: Let’s go back to the earlier discussion on the decision-making capabilities.

We have to assume that Xi is a rational actor, but he does not necessarily see or understand things the same way that we do.

One assumption is the commonly held one, that any potential invasion by the PRC would aim for a fait accompli. They do not want a long, drawn-out war of attrition here.

The problem with that is you would need to go with overwhelming force. You can do that by putting boots on the ground. You can do that through vast kinetic operations. Most people think the PLA Rocket Force will play a huge role in that.

But at the end of the day, you have to get boots on the ground. You have to secure a lot of the key infrastructure and airfields that you may not want to necessarily destroy. If your whole goal is unification, you want some of those key infrastructures. You want to protect the population the best you can.

The challenge is that the number of troops that you need to land exceeds the capacity of the Chinese Navy — even with the roll-on, roll-off civilian vessels — to get that number of troops on the ground at the same time. We just brought up the figure that really came from Thomas Shugart’s testimony before the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, where he stated that it would take roughly 10 days to deliver approximately 300,000 troops on the ground.

That probably is not enough troops, and that is probably too slow.

What that also doesn’t consider, too, is the level of resistance that Taiwan may have as these ships are sailing across the strait. I would caution everybody to say, “Hey, the numbers seem unreasonable for Xi.” He may see it differently.

The significant military debate that took place in 1944 in DC is probably not happening within the CCP today.

In the military, we like to say that good planning is usually top-driven but bottom-up refined. I don’t really know if that bottom-up refinement is happening, with voices saying, “We don’t have sufficient power to do this quickly. We can potentially do it, but the Taiwan military has a vote.”

The other thing is, how willing are you to get into a war of attrition over this? Is that healthy for the survival of the CCP? I hope that the PLA will have these discussions. Are they free to voice those concerns? I don’t know. That’s hard for anybody to speculate.

Jordan Schneider: Putin thought force ratios weren’t really all that important. He was leading with his military police, as if he’d just have to arrest some politicians, and he was flying special forces into Kyiv. The calculation there is not, “Oh, let’s look at all the land invasions and compare them to the battle of Kharkiv in 1944.” It was more like, “These guys are a paper tiger. They’re all corrupt. They’re all Nazis, and they don’t really feel like fighting anyways.”

The lesson for both Beijing and Taiwan is that Ukraine fought back. For Taiwan, the most effective thing would be to turn the discussion in Beijing from, “Oh, they’re not really going to fight” to, “Oh, wow, we really need to be counting up how many boats we can send, what our cadence will be, and what we’re going to do with the mines, guerrilla warfare, and point defense.”

Taiwan needs to communicate to Beijing both the capability and political willingness to fight.

That is not an easy thing to do, particularly in the Taiwanese context. Ukraine was already at war for 10 years before the invasion happened. That, God willing, will not be the case in the Taiwan question.

If Something Gives You Pause…

J. Kevin McKittrick: For me, one of the biggest lessons learned is the logistical requirements and constraints. We all saw what happened with the ill-planned logistical supply at the outset of the invasion in 2022. That only gets harder for an invading force when you have to cross a strait.

That is one of the key pieces in considering a China-Taiwan situation.

I would venture to say that a potential center of gravity at the operational level for the Chinese would really be their logistical system and their lines of communication.

There are multiple vulnerable points along that route — both at sea and even when ashore — that Taiwan could potentially target. Taiwan’s got a defense concept that overall is a pretty decent concept for them.

One of the things I noticed when I was reviewing the history of amphibious assault is the concept of an operational pause. This came from the CNA study as well. It’s the transition phase after you are on the beachhead. You have to go somewhere. The beachhead isn’t your overall objective. Units are going to have their sub-objectives. Maybe that is to seize a part of a city, maybe a key piece of infrastructure, or maybe an airfield.

They have to reorganize for combat, get their supplies, and get to the right formation and order of movement to get those things. That’s an extremely vulnerable spot for any army.

However, Taiwan’s overall defense concept does not seem to address the opportunity presented by China’s operational pause.

Nicholas Welch: You’re referring to Taiwanese Admiral Lee Hsi-Min’s 李喜明 four-part defense plan.

It starts with surviving the initial missile attack.

Then there’s the littoral battle as the ships approach.

Number three is the beachhead battle.

Number four is the defense of the homeland.

And if I understand it correctly, operational pause is the transition between the beachhead battle and defense of the homeland.

What kind of things would you specifically recommend Taiwanese military planners do to make sure this added fifth prong takes effect?

J. Kevin McKittrick: This is still a force-on-force fight at this point. A lot of people tend to think of homeland defense and then already go into something of a counterinsurgency mindset. There’s an opportunity before the military reverts to that.

Some of the things are very simple. You know they’re going to have to pause. You know if they can’t.

If it takes them 10 days to get 300,000 personnel on board, they’re going to have to build up the requisite combat power to move forward. You can counterattack at that point.

Also, what are you doing to target forces along just a few avenues of approach? Taiwan’s terrain does not favor an attacking force providing it with multiple avenues of approach to an overall objective. How are these targeted?

A lot of individuals talk about Taiwan and how the Chinese just simply need to destroy some of their major infrastructure roadways, and Taiwan defenders can’t get around. I don’t think a lot of discussion happens about what Taiwan needs to do to delay or defeat a Chinese force trying to go up those routes.

More analysis needs to be done on that. I propose looking more into that battle between the beachhead and the homeland defense. There’s more opportunity. If it’s tied to a holistic approach that targets the logistical lines of communication throughout the process, it sends a good message — especially a message of deterrence to China.

This isn’t necessarily going to be as easy as landing your guys on the beach. A lot of individuals have this perception of, “Hey, once everybody’s on the beach, the battle is over.” In some ways, it’s just beginning.

Nicholas Welch: Taiwan’s west coast isn’t suitable for an invasion not only because the beaches aren’t plentiful, but also because there also aren’t many highways from southern Taiwan to northern Taiwan. This is a huge logistical problem, as you were saying.

It’s a double-edged sword — whether Taiwan would want to hurt its own ability to move around, but also if it would be worth it to affect the PLA’s ability to move up and down the island. There’s really only one major highway that goes up the west coast of Taiwan.

J. Kevin McKittrick: Absolutely. Even the number of beaches is fairly limited. In Ian Easton’s book, he talks about there being only about a dozen or so beaches that are really suitable for any large-scale landing of forces. You can narrow down the potential approaches of where these forces would come from.

From there, the limited routes from those areas narrow it down even further. There are opportunities for the defender to focus in on that. Although the homeland defense aspect is extremely important, I don’t believe the fight transitions that quickly.

Jordan Schneider: Well, if any PLA planners or Chinese military bloggers would like to come on ChinaTalk to commiserate at the pain of planning this invasion, the invitation is open.

On a more serious note, I just think it’s a cool thing that you are allowed to do this podcast as an active service member on four days’ notice. This is not something that’s part of the culture in a lot of militaries, and not just China’s.

It just seems like a good and healthy thing to be able to have these sorts of intellectual discussions within the military in public.

Lessons for Taiwan

J. Kevin McKittrick: I want both Taiwan and China to walk away knowing a large part is going to come down to Taiwan’s resilience and how much it’s willing to defend itself. They can make this an even more difficult problem for China than it already is going to be. It’s important that message is sent as a form of deterrence.

The historical cases really bring that home.

A decent amount of literature talks about how the Chinese have studied the American island-hopping campaigns in World War II. But there is not much mention at all of Operation Causeway or why it didn’t occur.

I don’t know if that’s a case of only wanting to study successful invasions that actually happened.

I didn’t necessarily go into this project looking at it as an analysis of decision-making, but that’s where the research led. That’s the stark contrast I see between China and Taiwan today. Does the same level of experience and decision-making that existed in 1944 exist today? I would say no.

At the same time, that doesn’t necessarily make me feel any better, because we all know that misjudgments can sometimes lead to the greatest calamities. My only hope would be that maybe China does study a little bit of Operation Causeway and the decision-making that went into it. I hope they can get a better understanding that might prevent a war — one that isn’t beneficial to anyone on the globe.

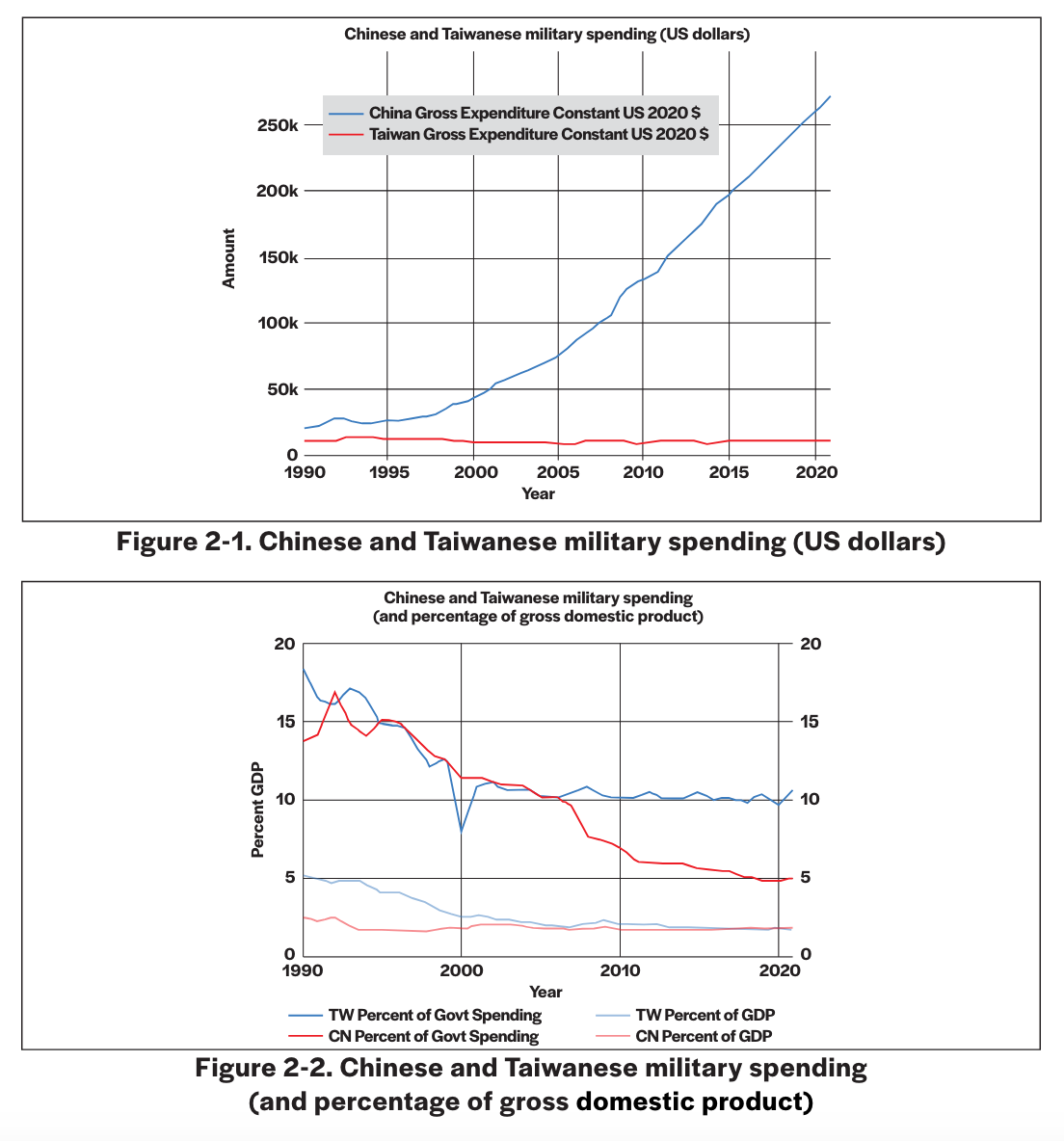

Jordan Schneider: Your point about force ratios suggests that, even if you’re Taiwan and your population isn’t as big, you don’t have to spend as much money on defense. A little goes a long way, because whatever you do, your adversary has to do two to four times more just to keep up and have a plausible way to succeed.

Nicholas Welch: The figures you cited in your report about Taiwan’s force ratios today are pretty remarkable. There are 94,000 active-duty army personnel in Taiwan. Wang Ting-yu 王定宇, a DPP legislator, said two years ago that there are only 300,000 army reservists who could respond to the call immediately.

So even if we say, pessimistically, that morale is bad and only half of the reservists (150,000) show up, we still have 244,000 Taiwan army forces ready to go at a moment’s notice. That means with a 3:1 force ratio requirement, the PLA would have to send 732,000 troops. If you want a 5:1 option, 1.2 million PLA forces would have to come across the Strait.

We want to invest in things that have an asymmetrical, disproportionate defense advantage.

One way to build Taiwan’s asymmetric defense is just by increasing the force numbers in Taiwan. Just showing up will make things a lot harder for an invading force in Taiwan.

J. Kevin McKittrick: I agree with that. It’s also making sure those forces that do show up are effective. Are they well-trained? Are they well-equipped? Numbers matter, what matters even more is when those numbers are good.

How McKittrick Got Into All This

J. Kevin McKittrick: This is probably a good time for me to address a little bit about how I got into this research. At the Air War College, I’m on a research task force. The research task force’s overall objective was how to deter conflict in the Taiwan Strait, on the margin, over the next ten years or so to cover — as Dr. McKinney usually likes to refer to it — as the “deterrence gap.”

My project focused on wargaming different scenarios. I focused on technology (like large UAVs), reserve forces, and what we could do better.

There’s a lot that can still be done to make the odds unequal in favor of Taiwan. It doesn’t always have to be about exquisite weapon systems.

I truly believe deterrence starts at the individual level. You’re showing up to fight — willing to fight and doing that effectively. There are many ways to do that — through commercial off-the-shelf technology, through different operational approaches.

That’s really what the crux of our research is about. You’re not going to find any revolutionary silver bullet. Often, in warfare, people like to get pulled into the flashy technology or the revolution in warfare.

Sometimes, I’d say a lot of times, it’s more incremental in practice. It’s doing the little things that add up overall, and then when you get the final tally, you have that overwhelming advantage. That’s what we hope that Taiwan would be able to do if they were invaded.

Nicholas Welch: How do I get on the research task force? Do I have to be a lieutenant colonel?

J. Kevin McKittrick: The Air War College is not just military. There are some civilians that go to the Air War College. Mostly, that’s DOD-affiliated civilians, but there are some other organizations within the government that also go. I was impressed with what everybody brought to the table in the discussion.

All of our projects will be published later on this summer in a book by Air University Press. The overall book is going to be called Closing the Deterrence Gap in the Taiwan Strait. The beauty is that it’s the opinions of the authors. Even though we are military or DOD-affiliated civilians, it’s not an official publication of the Department of Defense. We are individuals doing research. I think it’s healthy for the overall debate.

Bring Out the Big Guns

Jordan Schneider: Let’s talk about artillery for a second. This was not trendy, but all of a sudden, we have Jake Sullivan running around the globe convinced that 135-mm artillery shells are going to determine the fate of nations, which I don’t think was on anyone’s bingo card ten to twenty years ago.

What has been the role of artillery in the Ukraine war? What has surprised you about its evolution in the twenty-first century?

J. Kevin McKittrick: That’s a great question.

To borrow a quote from our artillery schoolhouse, there’s no better time to be an artilleryman than right now.

That’s something that resonates, especially with individuals around my age that entered the service about twenty years ago, really, at the start of the global war on terrorism.

I tell this story to my young officers. I remember coming in as a young lieutenant. At the time, I was in Ranger School, and I remember one of the instructors said to me, “It’s good that you’re here as an artilleryman, because your job is probably not going to exist in a few years.” Here you are — a young second lieutenant, that’s all eager to get out there into the force and do good things for his nation, and he’s basically saying the job you were trained for is operationally irrelevant before you actually get to your first unit.

That story always stuck with me: here we are, twenty years later, when long-range precision fires is the number-one modernization priority for the United States Army right now. The pendulum has swung fully in the same direction.

Part of that just goes to show there are some constants that you can’t dismiss. Yes, artillery was probably not the best weapon to fight a counterinsurgency. We’re talking about large-scale combat operations and the mass destruction it could bring. That’s what you’re seeing in Ukraine now. That’s why you have a resurgence, because we realized we can’t rely on an exquisite weapons system all the time.

There’s just something about being able to shoot 155mm rounds from a Howitzer without GPS guidance or precision — to accurately hit the target even in a degraded, decentralized environment when C2 systems aren’t what they should be.

The important lesson for us to take away is that you can’t just stop fighting because your systems don’t work. Artillery can still be, as we say, the king of battle on the battlefield. It can still be the lethal killer that it needs to be. Compared to other exquisite weapon systems, it doesn’t need a lot to be accurate — on the lower end of the spectrum, when we’re talking about 105mm, 155mm shells.

There’s also our long-range precision fires. We’re developing hypersonics and ground-based hypersonics. There’s always been a debate about whether we need redundancy. I think redundancy is necessary for resiliency. If one service had the sole, exclusive rights for hypersonics — whether they were air-, sea-, or land-based — I don’t think that’s healthy for a force. We need redundancy. We need resiliency.

As an artilleryman — shooting everything from the lower end of the spectrum with traditional cannon artillery to potentially manning hypersonic batteries — I am in firm concurrence that it is a great time to be an artilleryman.

Jordan Schneider: What do you think about the logic of having a rocket force in America? What is your sense of the pros and cons?

J. Kevin McKittrick: Overall, a con that comes out to me: we say as artillerymen, as artillery officers, that we consider ourselves fire supporters first. We are inherently — and we have been for a long time in our army — a maneuver-centric force. It is all about how we put the maneuver commander, at the battalion level or at the corps level, in a position of overmatched advantage.

If you have a separate rocket force, if you separate a lot of that artillery, you lose some of those habitual relationships. You may potentially lose some of that combined arms capability and working knowledge. That, to me, seems like the biggest hesitancy to having a completely separate rocket force.

We can still accomplish those missions pretty effectively. The way we train as artillerymen, both in the direct support artillery as well as the more general support. When we start talking about HIMARS or MLRs, the one advantage, as we always understand it, is putting the maneuver commander in a position of overmatched advantage for victory. Some of that might be lost if we decide to split off.

Jordan Schneider: What’s the bull case for it?

J. Kevin McKittrick: The bull case for it is just like anything else. Whenever you have a new service, it comes down to resourcing. It’s better to advocate for resourcing as its own service. I don’t necessarily see that as a big issue today. As I said, the Army’s number one prioritization is long-range precision fire, so we’re in a good case today.

I would say separate services really exist in our army to man, equip, train, and resource the forces they provide to combat commanders. Overall, we’re in a good position right now. While having a separate service may allow us to do that slightly better, the tradeoffs would not be worth it.

Amazing post!

Very peculiar that all the discussion is about beaches and highways in Taiwan.

Surely the battle would be at sea, a duck-shoot, and on the Chinese mainland, the ports and their supporting areas, where a quarter or half a million PLA support troops would be cowering.