Xi on Art and Political Control

"It is not desirable to use artistic works as tools for catharsis."

The following annotated translation is by Zac Haluza. He writes Cloudology, a newsletter focusing on cloud and tech news from China. You can find him on Twitter @zac_haluza.

In his opening speech for the 20th Party Congress last night, Xi Jinping made a point to emphasize the importance of increasing China's cultural strength and self-confidence. This included "fulfilling the growing spiritual and cultural needs of the people and solidifying the common ideological foundation upon which the Party and all the peoples of the nation strive in unity."

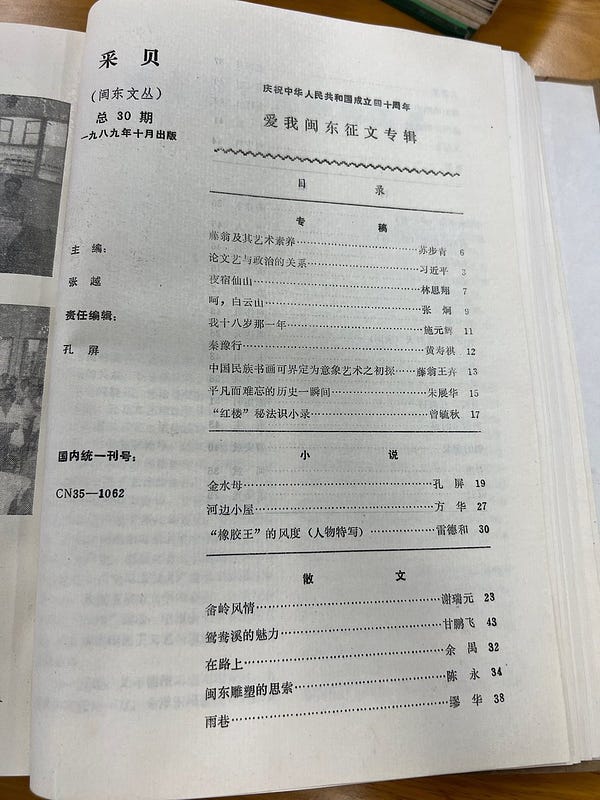

The roots of Xi's views on culture and its role in Chinese society go back decades, as can be seen in a 1989 article (recently shared by Washington Post reporter Eva Dou) in which he discussed the arts in the context of modern China. At the time of writing, Xi was the 36-year-old Party secretary of Ningde in Fujian Province.

The ideas introduced in this article are not that unusual for an up-and-coming Chinese politician in the late 1980s — largely because they’re generally cut from established Party ideology. His main points draw alternately from Marx, Mao Zedong, and Deng Xiaoping, adapting them to a contemporary Chinese context. Over the course of his article, Xi argues for freedom in the arts, as well as artistic criticism, but admits that a certain level of state involvement is necessary to ensure that the arts can act as a positive force for social progress and national unity.

As many have noticed, this article was published after widespread protests rocked China, including Xi’s then-home of Ningde, throughout the spring and summer of 1989. This period of social unrest and political turmoil may have inspired Xi to denounce a recent, intentionally provocative avant-garde exhibition (an example of the ‘85 New Wave movement, which faded by the end of 1989 but left its mark on contemporary Chinese art). Yet Xi also warns against the strict political and ideological control of the arts. He cites the art of the Cultural Revolution as an example of how this can lead to undesirable consequences. Throughout the article, he cautions against both the unchecked freedom of the arts as well as tight political control.

This article also doubles as an informative primer on the PRC leadership’s views on art through the 1980s. Referencing everything from Engels to Mao’s talks at the Yan’an Forum and post-Cultural-Revolution scar literature, Xi lays out a sweeping overview of China's policies on the arts and the artistic movements that developed within the developing nation.

Below is a revised and expanded version of the translation of this article originally published by USCNPM (many thanks to Michael Cerny for allowing its use here). It has been heavily annotated to explain various historical and cultural references.

ChinaTalk is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber!

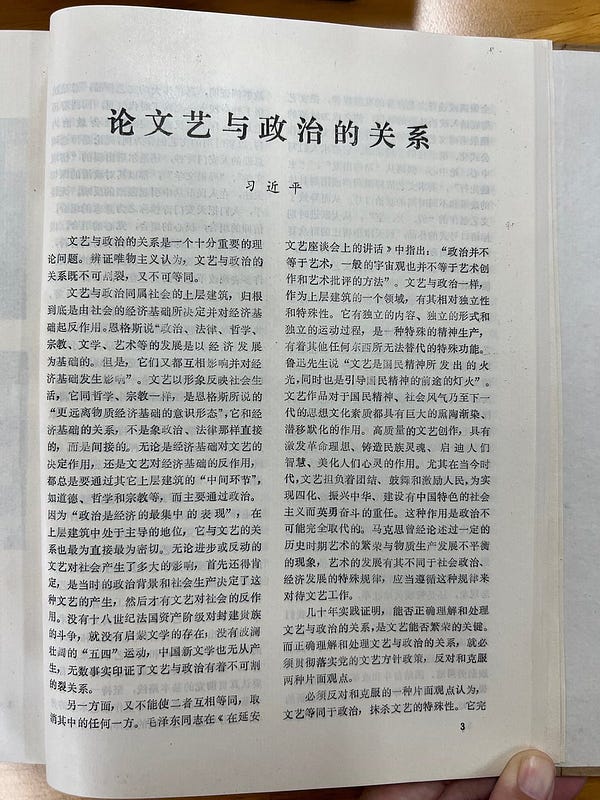

On the Relationship between the Arts and Politics

by Xi Jinping

The relationship between the arts and politics is a theoretical issue of great importance. Dialectical materialism holds that the relationship between the arts and politics can neither be separated nor equated.

Both belonging to the superstructure of society, politics and the arts are fundamentally determined by and have a reactive effect on society’s economic base. As Engels says,

… political, juridical, philosophical, religious, literary, artistic, etc., development is based on economic development. But all these react upon one another and also upon the economic base.

The arts use imagery to reflect social life. Similar to philosophy and religion, the arts are “an ideology that distances itself even further from the material-economic base,” to quote Engels. Unlike politics and law, the relationship between the arts and the economic base is not a direct one, but rather an indirect one. Both the economic base’s decisive impact on the arts and the influence of the arts on the economic base demand another “intermediate link” in the superstructure, such as morality, philosophy, or religion, though mainly through politics. This is because “politics is the most concentrated expression of economics” and maintains a dominant position among the superstructures. It holds the most direct and immediate relationship with literature and art. No matter how much influence progressive or reactionary literature has had on society, it must first be affirmed that contemporary socio-political contexts determine the creation of such art before it can influence society. There would have been no Enlightenment literature without the struggle of the French bourgeoisie against the feudal aristocracy; there would have been no New Literature in China without the spectacular May Fourth Movement. [Ed.: New Literature is a broad classifier for literature spanning from the days of the May Fourth Movement to today, characterized initially by the use of vernacular language.] Countless pieces of evidence affirm the inseparable relationship between the arts and politics.

On the other hand, these two things cannot be made equal, lest one becomes eliminated. Comrade Mao Zedong, in “Talks at the Yan’an Symposium on Literature and Art”, maintains that “politics cannot be equated with the arts, nor can a general worldview be equated with methodologies of artistic creation and criticism.” Like politics, the arts are part of the superstructure of society and are relatively independent and distinct. They possess independent content, form, and process. They are a special sort of spiritual production with an irreplaceable function. As Mr. Lu Xun writes, “The arts are both the fire emitted by the national spirit and the lamp that illuminates its future”. Artistic works have a palpable influence on the national spirit, the social atmosphere, and even the ideological and cultural tendencies of the next generation. High-quality artistic works may inspire revolutionary ideals, shape the national spirit, bring enlightenment, and beautify the soul. Especially in the present era, the arts carry the important duty of uniting, inspiring, and motivating the people to achieve the “Four Modernizations,” to revitalize China, and to achieve socialism with Chinese characteristics. [Ed.: First introduced in the 1960s and put into action by Deng Xiaoping in 1979 (a decade before this article was published), the Four Modernizations refer to modernization in industry, agriculture, national defense, and science and technology. At the time of publication, this now-ubiquitous phrase — “socialism with Chinese characteristics” — had been in usage for 7 years, having been first used by Deng Xiaoping in his address to the 12th National Congress in 1982.] This cannot be accomplished by politics alone. Marx has described the phenomenon of unbalanced development in the arts and material production during certain historical epochs. Unlike society’s political and economic development, the arts develop according to their own rules. The arts should be viewed according to these same rules.

The past decades have shown that the ability to correctly understand and handle the relationship between the arts and politics is the key to artistic prosperity. In addition, correctly understanding and handling the relationship between the arts and politics requires the implementation of the Party’s policies on the arts as well as opposing and overcoming two biased viewpoints.

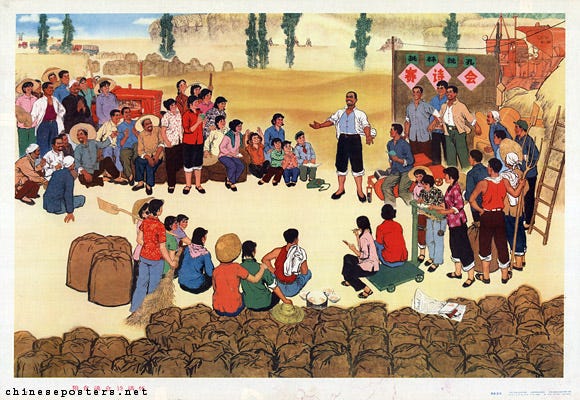

One biased viewpoint that must be opposed and overcome is that the arts are equal to politics, which erases their unique nature. This view completely deviates from, or contradicts, the laws of artistic development by integrating the arts into political struggle, thereby constraining the arts and turning them into a replica of politics. This view is the ideological origin of transforming artistic creation into a formulaic, conceptualized undertaking. It requires people to write about and discuss its core and to emphasize its “political line” or “theme.” It requires the arts to follow a set model or to demonstrate specific policies and political slogans of different periods. This leads to the “falsity, grandiosity, and shallowness” of artistic creation. [Ed.: Not a quote, but a common expression. A quick Baidu search can see it leveled against such targets as (surprisingly!) modern art.] The works consisting of slogans during the Great Leap Forward, the poetry competitions in Tianjin’s Xiaojinzhuang Village, and the widely popular model theater pieces during the Cultural Revolution all demonstrate that following such a narrow path would not only dismember the special function of the arts and destroy their proper role; moreover, it would bring about the confinement of people’s thoughts and the suffocation of artistic life.

[Ed.: According to Baidu, this village became nationally famous for its poetry competitions during the Cultural Revolution. Xiaojinzhuang's ties to the Cultural Revolution extend later to the period when the Gang of Four came to prominence for their participation in proletarian and anti-reactionary movements — Jiang Qing herself visited the village with guests from abroad. The village was later criticized for these "experiences" following the fall of the Gang of Four. The "eight plays for 800 million people"/八亿人民八个戏 is a reference to the "model theater" that became popular during the Cultural Revolution. The eight pieces referenced here consist of five Beijing opera pieces, two ballets, and one symphony. As their name suggests, the "eight model theater pieces" (八大样板戏) were selected in particular as "model" performance pieces during the period of the Cultural Revolution. “Narrow path” was literally "hutong" in the original text.]

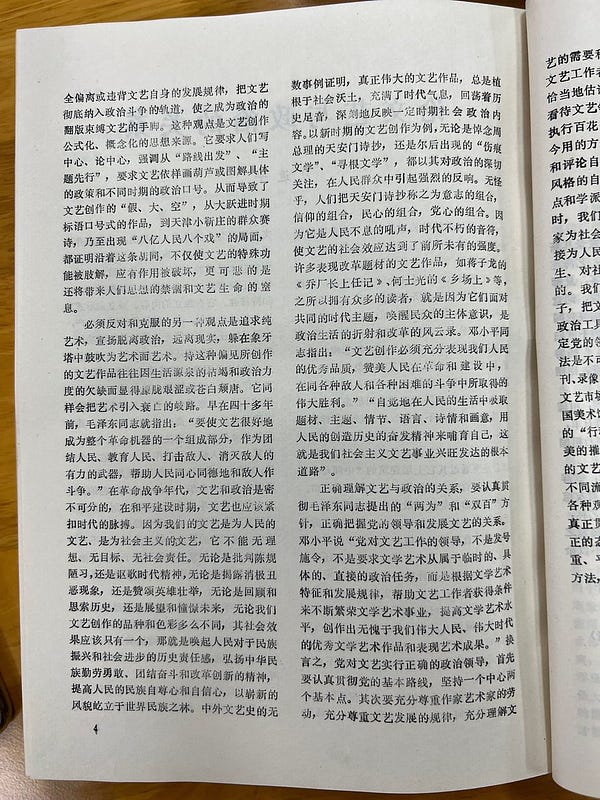

Another view that must be opposed and overcome is the pursuit of pure art. This view promotes detachment from politics and reality, to hide in an ivory tower and champion art for art’s sake. Artistic works created with this prejudice are often obtuse or colorless because they are disconnected from life, the source of art, or lack political strength. This view will likewise lead art down a path of decline. Only four decades ago, Comrade Mao Zedong pointed out: “The arts should be well established as part of the revolutionary machine, as a powerful weapon for uniting the people, educating them, and attacking and destroying the enemy. It should help the people unite in their struggle against the enemy.” During the revolution, the arts were inseparable from politics. In times of peace and development, the arts should also keep pace with the times. Because our arts are for the people and for socialism, they cannot be without ideals, goals, or social responsibilities. Whether a work criticizes outdated customs, sings the praises of the zeitgeist, reveals negative and vile phenomena, extols heroic feats, reflects upon history, or gazes longingly upon the future — no matter how much our artistic works differ in style and tone, they should have only one social effect: to arouse people’s sense of historical responsibility for national rejuvenation and social progress; to promote the spirit of hard work and bravery, unity and struggle, and reform and innovation of the Chinese nation; and to raise people’s national self-esteem and self-confidence.

Numerous examples in the history of both Chinese and foreign art have proved that truly great artistic works are always rooted in social contexts, are rich with the spirit of the times and the footprints of history, and they reflect deeply on the sociopolitical aspects of a given period. To choose several examples from the New Period, from the Tiananmen Poetry movement, which mourned former Premier Zhou Enlai, to the “scar literature” and “root-seeking literature” which appeared later — these works all stirred strong sentiments among the people due to their deep political focus. [Ed: “New Period” is defined as the period beginning in December 1978, which marked the beginning of the Reform and Opening Up period under Deng Xiaoping and a shrugging-off of the burdens of the Cultural Revolution. Astute readers may also compare this phrasing to Xi Jinping's own "New Era," which he announced in 2017.] It is not surprising that people called Tiananmen poetry a combination of determination, faith, the will of the people, and the will of the Party. The arts had a social effect of unprecedented strength because they were the unceasing roar of the people and the undying peal of the era. Many artistic works on the theme of reform, such as Jiang Zilong’s Manager Qiao Assumes Office and He Shiguang’s The Rural Market, enjoyed a large readership because they faced common contemporary themes and awakened people’s perceptive consciousnesses; they are mirrors of political life and records of the sudden changes during a period of reform. Comrade Deng Xiaoping pointed out, “Artistic creation must fully express the excellent qualities of our people. It must praise the great victories achieved by the people in revolution and construction, and in the struggle against all kinds of enemies and difficulties… The fundamental path to the prosperous socialist literary and artistic cause consists of voluntarily planting oneself into the lives of the people, absorbing subject matter, theme, plots, language, and artistic beauty.”

To correctly understand the relationship between the arts and politics, we must conscientiously carry out Comrade Mao’s guiding principles of “serving the people and serving socialism” and letting “a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend,” and correctly grasp the relationship between the Party’s leadership and the development of literature and art. [Ed.: Xi says 两为 (liang wei) but appears to be referring to what's commonly referred to as Mao's 二为 (er wei) principle. “Serving the people and serving socialism” was first uttered by Mao at the Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art in 1942 (which was mentioned previously in the article), from his discussions of how the arts could and should be used in service of the people and revolution. The “hundred flowers” principle, known as "shuang bai" (双百), was directed towards scientific and cultural development. The intention was, as the phrase suggests, to encourage progress through the free development of different schools of thought. This principle dates back to 1956, over a decade after Mao first discussed "serving the people and serving socialism," known as "er wei." The two principles of "er wei" and "shuang bai," which represent complementary perspectives on the purposes and uses of the arts over the course of Mao's leadership, are often mentioned in tandem.]

Deng Xiaoping said, “The Party’s leadership of artistic work is not to issue orders or subordinate the arts to temporary, specific, or direct political tasks. Rather, the Party, in accordance with literature’s and art’s respective characteristics and rules of development, helps artistic workers obtain the conditions to continuously make literature and art prosper, to raise the standards of literature and art, and to create excellent literary works and expressive art pieces worthy of our great people and our great times.” In other words, to exercise correct political leadership over the arts, the Party must first conscientiously carry out the Party’s basic line of “one central task and two basic points.”

[Ed.: “One central task and two basic points” was declared in 1987 by Zhao Ziyang, who was general secretary of the Party from 1987 until shortly before this article's publication in 1989, reportedly due in part to clashes with then-Premier Li Peng regarding his handling of the 1989 Beijing protests. The "central task" refers to building the economy, while the "two basic points" refer to Deng Xiaoping's Four Cardinal Principals declared in 1979 (to uphold the socialist road, the dictatorship of the proletariat, the leadership of the Party, and Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought) and to persevere in Reform and Opening Up. Interestingly, Xi used this phrase in 2014 to refer to the diplomatic strategy of China's new administration. In this context, the "central task" referred to diplomacy with nearby states, and the "two basic points" referred to the Belt and Road policy (literally "one belt, one road" in Chinese, hence the "two points").]

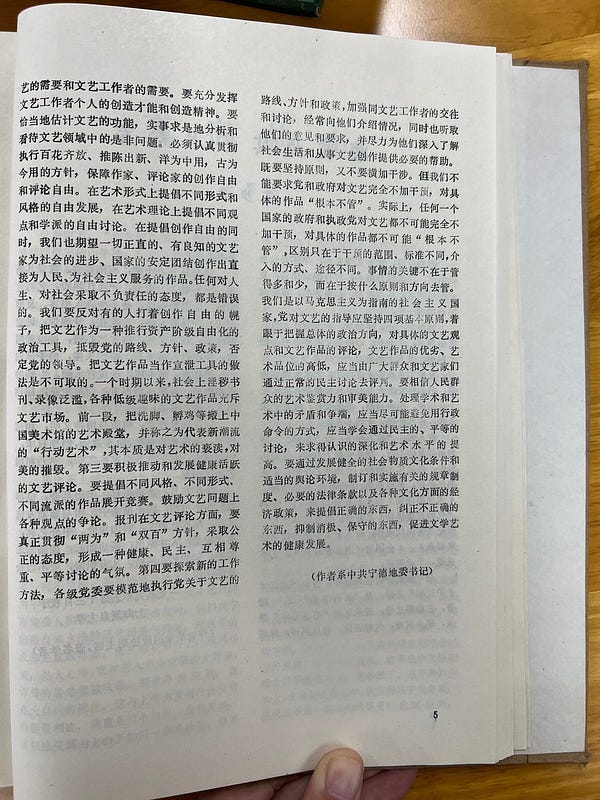

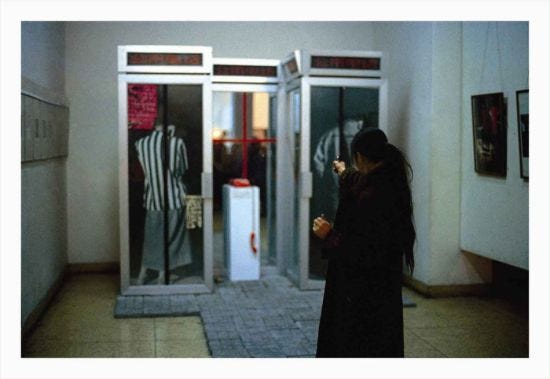

Second, we must fully respect the labor of writers and artists, fully respect the laws of artistic development, and fully understand the needs of the arts and of artistic workers. We must give full play to individual artistic workers’ creative talent and spirit. The function of the arts should be properly estimated, and the issues of right and wrong in the field of literature and art should be analyzed and viewed realistically. We should take sincere actions to implement the blooming of different schools of thought, the replacement of the old with the new, making ancient things serve the present day and making foreign things serve China, and guarantee the creative and critical freedom of writers and critics. [Ed.: These all refer to artistic and cultural concepts promoted by Mao Zedong (the first is a repetition of the "shuang bai" principle mentioned above).] We should advocate for the free development of different forms and styles in art, and for the free discussion of different viewpoints and schools in art theory. While advocating for the freedom of creation, we also expect all artists with integrity and conscience to unite to create works that directly serve the people and socialism for the sake of social progress and national stability. Any work that adopts an irresponsible attitude toward life and society is incorrect. We must oppose those who, under the guise of freedom of creation, use the arts as a political tool to promote bourgeois liberalization, slander the lines, guiding principles, and policies of the Party, and negate the leadership of the Party. It is not desirable to use artistic works as tools for catharsis. For some time, obscene publications and videotapes have flooded society, and artistic works of low taste have flooded the artistic market. Recently, foot washing and egg hatching were on display in the National Art Museum of China and referred to as “behavioral art” representing the new wave. The very essence of these works was a desecration of art and a spoliation of beauty. [Ed.: Credit to Eva Dou for sharing and Joseph Torigian for tracking down this article that discusses the avant-garde exhibition that Xi is referencing, featuring hurled condoms and an artist who shot her own art. The phrase "new wave" could also refer more largely to the avant-garde 85 New Wave movement (1985-1989).]

Third, we should actively promote and develop healthy and active artistic criticism. We should advocate for competition among works of different styles, forms, and genres. We should encourage debate among varying views on artistic issues. Regarding artistic criticism, publications should properly implement the guidelines of serving the people and socialism and letting different schools of thought bloom, adopt fair and impartial attitudes, and form a healthy, democratic atmosphere of mutual respect and equal discussion.

Fourth, we should explore new work methodologies. Party committees at all levels should carry out the Party’s lines, principles, and policies concerning the arts in a standard manner, strengthen exchanges and discussions with artistic workers, and update them regularly on the current situation. [Ed.: Xi is implying here that artists should shape their work to fit the current social/political/etc. situation.] At the same time, we should also listen to their opinions and needs and do our utmost to provide them with the necessary help to facilitate their in-depth understanding of social life and their engagement in artistic creation. We should adhere to our principles while refraining from excessive interference. However, we cannot ask the Party and the government not to intervene in the arts at all or to adopt a “hands-off” attitude to the specific works themselves. In reality, the government and ruling party of any country cannot avoid intervening in the arts, nor can they adopt a “hands-off” attitude toward works of art. The difference lies only in the scope and standard of intervention, and the particular methods of intervention. What matters is not how much or how little to regulate, but which principles and direction to follow when doing so. We are a socialist country guided by Marxism. The Party’s guidance of literature and art should adhere to the Four Cardinal Principles, and we should focus on maintaining our grasp on the overall political direction. [Ed.: The Four Cardinal Principles are to uphold the socialist road, the dictatorship of the proletariat, the leadership of the Party, and Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought.]

Specific views on and criticism of artistic works, their merits, and their taste, should be judged by the masses and by artists through normal democratic discussion. We must trust the people’s artistic tastes and aesthetic abilities. To deal with contradictions and disputes in academia and art, we should avoid administrative orders as much as possible and learn to deepen our understanding and improve our artistic standards through democratic and equal discussion. Through the development of sound social, material, and cultural conditions, and the formulation and enactment of relevant regulations, necessary legal provisions, and various culture-related economic policies, we can promote things that are correct, rectify those that are incorrect, resist negative and conservative things, and promote the healthy development of literature and art.